In her work, Paraguayan filmmaker Paz Encina (born 1971) combines fiction and archival material, precise imagery, and an unusual focus on sound to address issues that mark the history of her country—like the Chaco War (1932–35), the long dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner (1954–89), massive deforestation, and the displacement of indigenous communities. Her first feature film Hamaca paraguaya (2006) was released to critical acclaim and won the FIPRESCI Award at the Cannes Film Festival. Soon after Encina completed her second feature, Ejercicios de memoria (2016), MoMA organized a retrospective of her work. This conversation took place as she was finishing her fourth feature, Eami.

For the Spanish version of the interview click here.

Silvina López Medin: As a child you learned musical notes before the letters of the alphabet, and you have talked about a “musical structure of thought.” In your films, there’s a sort of dislocation between image and sound. Could you talk about that relationship in your work?

Paz Encina: I think that the structure of thought I talk about might be read as a dislocation between image and sound because, somehow—in the way we usually read the world—it is a dislocation. But having learned the musical notes first, reading the world through time became natural to me. Sound is time. Music is time. You use measures in order to start writing music; you mark time, and the musical notes have certain time durations that—when mixed together—coexist. So although this structure of thought might be read as a dislocation between image and sound, it can also be read as a coexistence of different times. What interests me is to be able to communicate this multiplicity of times that coexist within a human being inasmuch as, I think, we are simultaneously Memory and the present moment.

SLM: In Hamaca paraguaya (Paraguayan Hammock), this “dislocation,” or coexistence, is embodied through your use of voice-over throughout the film. There is a fracture between image and sound. As if the two characters awaiting news from their son, who has left them to fight in the Chaco War, were at a loss for words because of their anguish. Words do not come out of their mouths, but we can still hear them, asynchronously. What was your idea around this use of voice-over?

PE: Those voices-overs are like a ceremony that takes place every day . . . I thought of this ceremony as a useless mass. It’s what they live that day, but it’s also what they have been living for who knows how many years. It’s the time of grief, which is always endless. Time has turned those parents—who have lost their treasured son—into a sort of still life over which light passes . . . time has passed over them and keeps passing over them. And, also, to keep hearing those same voices—even if it’s only in their memories—is for me an act of love. A way of holding onto a life that’s lived for the other.

SLM: In Ejercicios de memoria (Memory Exercises), there is a tension between the peaceful images of children playing in nature (the present time of the film) and the voices of the grown children of Agustín Goiburú (1930–1977)—a “disappeared” Paraguayan opposition leader—who speak of a past marked by the fear and violence of Stroessner’s dictatorship. These images of children playing in nature could be thought of as a staging of those little moments of play that Goiburú’s children talk about as being limited in their own childhood. How did you come up with the idea of the camera following these children in relation to the narrating voices?

PE: The first thing I did for this film was to travel with Agustín’s children to the fourteen houses they had lived in while in exile. We traveled from city to city, from house to house, and there, while their memories arose within them, I felt that all they were telling me, they were telling from their childhood. I felt like they were a family that had once shared happiness, and that that happiness somehow had lasted, although this lasting might be wounded. That’s why I worked on the idea of “that which is wounded.” In the film, the fruits are wounded, the cutlery is wounded, the children have wounds, everything is wounded, but it doesn’t mean that beauty doesn’t persist in all of this.

Regarding the camera—that was a decision that I made together with Matías Mesa, the prodigious cinematographer of the film, who asked me whose point of view the film is from. It’s Agustín’s, I answered him. It’s as if Agustín were with them. They are kids, I thought, one needs to be near them, take care of them, keep them company. They shouldn’t be left alone.

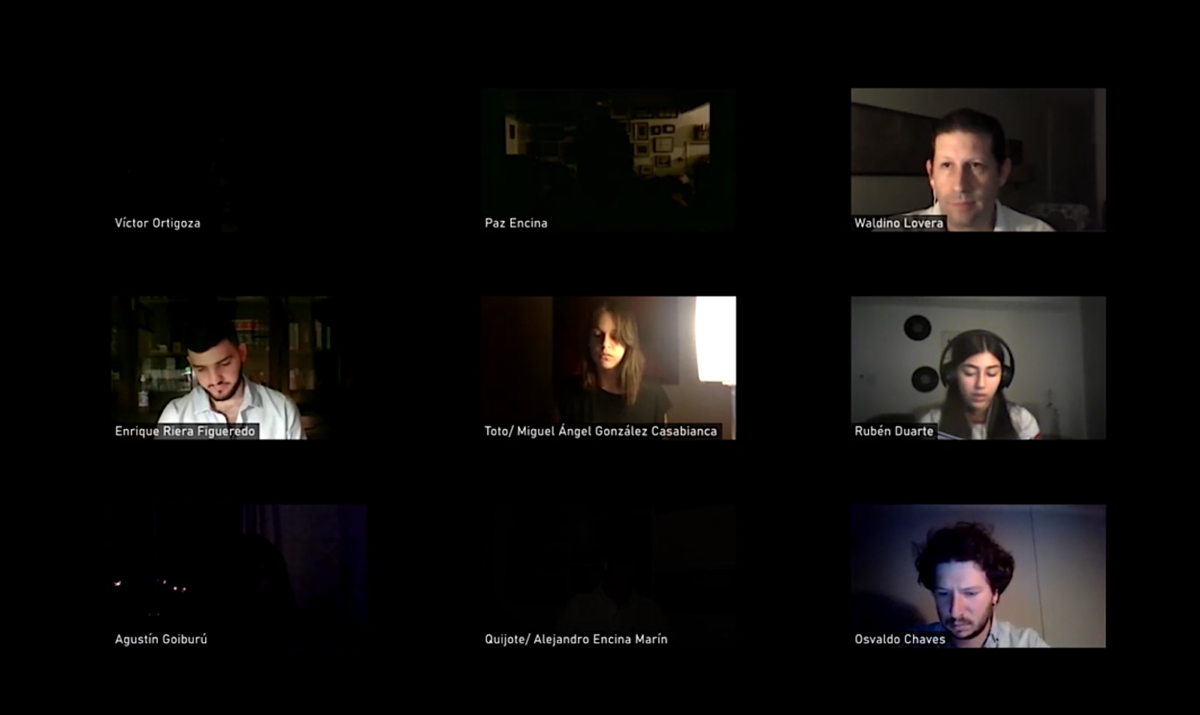

SLM: In your last film, Veladores (2020), the grandchildren of several members of MOPOCO (Popular Movement of the Colorado Party) read the old letters that their grandparents wrote while in exile because of their opposition to Stroessner’s dictatorship. Just as in Ejercicios de memoria at times the voices overlap and at times they separate as if following a musical score, here we see faces that embody a sort of chorus of voices. What was your process in composing this “score”?

PE: Veladores was born in an unexpected way. One of my nephews, Nahuel, wanted to learn more about my father, and because of pandemic restrictions, we would meet on Zoom. Once when we were talking about my father’s political life, I showed him those old letters, and while the two of us were reading them, I thought, “That’s it!” I had had those letters with me for twenty-five years but I had never found a way to talk about them, to read them, to make those words resonate in a film. I had the certainty of the formal aspect of the film for the first time, and then I put the letters together and, with a small team that I assembled, we read all of them. We realized that they needed a script, which I wrote in about two days . . . those letters were already so deep inside me that very soon, I was able to put together a score in relation to a dialogue that builds between the letters. And precisely because of exile, half of those grandchildren live in Argentina and half of them live in Paraguay, and so I thought that Zoom was a good way to bring them together and to have those letters read again. It was a good way for the words to be heard again.

SLM: In Veladores, your formal approach really caught my attention: you manage to transform an image we have seen so many times during the pandemic (the gallery view and speaker view on Zoom) into a powerful mise-en-scène. Not only do I find a visual connection to the pandemic, but also I find a thematic one. That forced distance of exile that’s talked about so much in the letters somehow brings to mind the pandemic—of course, with very different causes, consequences, and nuances.

PE: I think that’s the strength of Veladores—a formal approach that contains a tale that on its own might well be a deluge of things. I think that Hamaca and Veladores are the most solid films I have made, the strongest from a formal point of view. In Hamaca, the passing of time and the sadness might have overflowed if the formal aspect hadn’t contained them. And I feel the same way about Veladores, which is almost a maternal gesture . . . a gesture that holds and contains all these feelings.

SLM: In Spanish, the title, Veladores, has multiple meanings. The veladores (table lamps) are an essential part of the setting of the film (each character turns on a lamp before starting to talk). Also, these children reading their grandparents’ letters could be thought of as veladores in the word’s other Spanish meaning: they are watching over their suffering, long-dead relatives. And they are safeguarding (yet another meaning of the word) those experiences, too. Veladores is also a word that could be applied to the characters of your other films: the parents in Hamaca paraguaya, Goiburús’s children in Ejercicios de memoria. The word veladores also has to do with the idea of “shedding light” on certain moments in history, which is something you yourself do in all of your films. Ten years passed between your first feature and the second one. Is your work at the Archives of Terror1The “Archives of Terror” is the name of a set of official documents related to police repression in Paraguay, particularly during the period of Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship. See https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/CDyA/index.htm. connected to this lapse between films?

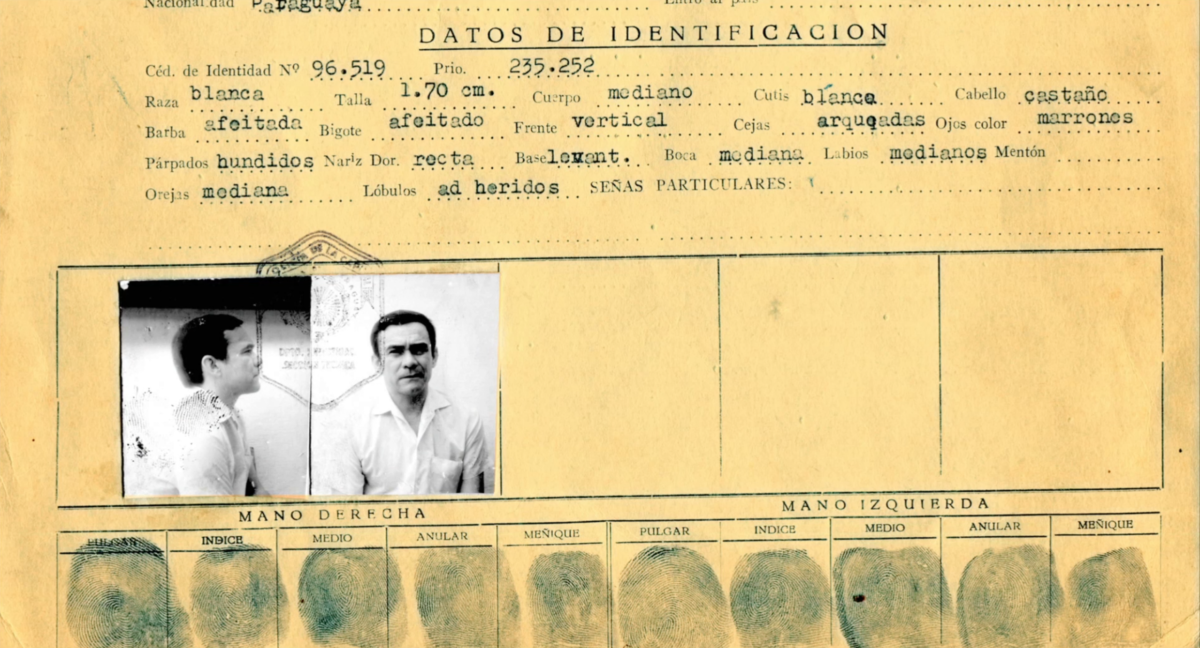

PE: No . . . what happened was that between my first and second features, another feature fell through. It was called (is called) Un suspiro (A Sigh). Complicated and sad things happened, and I found myself returning funds and not being able to make a film after all that had happened with Hamaca. This affected my life enormously, and it was similar to going through a grieving process. Amid that grieving (how strange—this is the first time this has occurred to me), I went to the Archives of Terror. My work there began around 2010, when I realized that even though I had lived through the dictatorship, and that that background could help me talk about it, I wanted the dictatorship to be an object of study. I watched and listened to all of the archival footage. All of it. It was terribly hard; it was an attempt to understand with adult eyes something that I had lived closely, from the point of view of a child, because my father had been an opponent, had been exiled twice, had been in prison, and we used to live near detention and torture centers . . . I felt that I needed to recordar (remember) again, or re-cordis, to pass everything again through the heart. That was the point of going back to the Archives. While going through them, I recognized many people . . . my parents’ friends or professors at the university . . . I recognized my friend’s grandfather because he had my friend’s eyes . . . I didn’t need to read the names . . . I knew who they were . . . It must have been intense for me because three short films came out of this period—Arribo (Arrival), Familiar (Familiar), and Tristezas (Sorrows), a trilogy I call Tristezas de la lucha (Sorrows of the Struggle)—as well as several installations and the feature Ejercicios de Memoria. Veladores, which came later, was like “shedding light,” even on myself. It meant finding a sort of closing to a circle that had always remained open, not because through all of this I’m done with the subject of the dictatorship, but because I felt that this cycle was over.

SLM: In Ejercicios de memoria, the first image after the opening credits is a glass window that merges the interior (a “still life”) and the exterior (“living nature”). This gesture of blurring a border makes me think of the blurry line between fiction and documentary in your works. For instance, in Ejercicios there is a scene in which a woman puts down the piece of embroidery she is working on and then a door opens literally and metaphorically: there is a direct shift to archival material (photos of detained people). And at the level of sound, there is a shift from birds singing to the metallic noise of a recorder and the voice of an informant speaking to the police. What is the relationship between fiction and documentary for you?

PE: This relationship, which generally seems to be conditional or contradictory, works in me somehow organically. I think this is a kind of freedom that music introduced to me, this feeling that there are things that can coexist . . . times, forms. There’s a moment when I don’t wonder if I’m making fiction or documentary—sometimes I’m not even able to recognize the limits between one and the other. I think in terms of stories, and if something that we call “documentary” will help clarify things in what we call “fiction,” or vice versa, then fine. What I want is to be able to find life . . . if I find that in a documentary gesture, I’ll go that way, but if I find life in fiction, then I’ll go that other way. What interests me is to capture truth . . . from my own perspective. Rilke said, “If it burns, it’s because it’s true.” That’s my path: if it burns, if it burns me, then that’s the image. I think that separating documentary and fiction into categories, as if they were totally opposing things, is part of a cultural construction.

SLM: There’s a moment in Ejercicios when what’s playing on the radio changes from a political rally to a sweet guarania (a kind of slow and melancholic Paraguayan song). This song talks about love and about the beauty of the Paraná River, which is also the river into which the bodies of people tortured during the dictatorship were thrown, as Agustín Goiburú reported. This brings to mind the juxtapositions of images of people dancing and fingerprints of detained people in your short film Familiar. Is this combination of seemingly disparate elements connected with your own experience during the dictatorship?

PE: Yes. That was somewhat my experience, which was a bit contradictory. Behind closed doors we knew well what we thought, or what our parents thought and wanted, but to the outside world, my sister and I were little girls who took ballet lessons and danced at the municipal theater, which was half a block away from one of the worst repression centers in the country. And as a child, I knew what was going on there; in fact, I was even afraid to pass by it, but then I would enter the theater and feel sort of “safe.” We attended schools where our classmates were the children of high-ranking Stronists (Stroessner supporters), and we couldn’t tell anyone what we talked about at home . . . I always had the uneasy sensation of being a participant in those contradictions. I was a child and I couldn’t understand everything clearly, but I felt inside me that something didn’t fit.

That song playing in Ejercicios is “Mi pequeño amor” by Ramón Ayala, who was a close friend of Agustín. I hardly ever play songs in my films, but in this case, there was no question but that I should. It was a song from Agustín to his wife and, at the same time, it was a song from me to Paraguay.

SLM: The dictatorship, exile, and waiting are all recurring themes in your films. In Hamaca, the hammock itself works as a condensing element: it holds both characters together, in the air, in the suspended time of awaiting a son’s return. One of the themes in Ejercicios and Veladores is exile, that other kind of suspended situation, and waiting is also a theme—waiting to return to the homeland, and the long wait, thirty-five years, for Stroessner’s fall. You have said that “Stroessner is no longer in Paraguay, but Stronism is still here.” How is your work received in Paraguay?

PE: My films are seen in Paraguay thanks to this sort of “hideout” that people find on social media. Many of my films can be freely downloaded from my Vimeo site, and though from there I can count how many times they are seen, nobody ever tells me that they saw them. It seems to be a secret that deep inside I completely understand, because the economic and social power is still in the hands of Stronists. I can’t imagine that this will change soon. Fear, privileges, and even repression are still deeply rooted in Paraguay. Perhaps people are less afraid that they will be imprisoned, but they still fear that they might be fired or ignored or “blacklisted.” You still pay a high price for being anti-Stronist.

SLM: How do you work on the script?

PE: I write scripts, but they end up being sort of maps that I don’t stick to. I always begin with the sound design and it is only later that I deal with the visual aspect of the film.

SLM: Hamaca is fully in Guaraní. What is your relationship with that language?

PE: Guaraní is natural to Paraguayans; both Spanish and Guaraní are our official languages. Moreover, most of the Paraguayan population speaks only Guaraní. During the dictatorship, they tried to nullify the Guaraní language. But it was impossible to make it disappear because it has an oral tradition, and because it’s part of the structure of a population that thinks in Guaraní, makes jokes in Guaraní, and only in Guaraní is able to express what they feel deep inside. All that is true is said in Guaraní, and the rest is said in Spanish. There’s the common use of Jopara, which is a mix of Spanish and Guaraní.

SLM: What are you working on now?

PE: I’m finishing Eami, a film I made with the indigenous community Totobiegosode. Eami is a word that means Forest and also World. This is my fourth feature, and as with everything I do, it’s about exile, diaspora, the fragility of life . . . what stays with us as Memory . . . I’m exploring the forced migration caused by the massive deforestation of the Paraguayan Chaco, which is the most deforested territory in the world. I think the film is a bit sad, but it is also quite sweet. It’s a co-production between Paraguay, Argentina, Holland, France, and Germany. I’m about to travel to Mexico to do the sound mixing and then the film will be done. We’d like to launch it this year.

Translated from Spanish by Silvina López Medin.

- 1The “Archives of Terror” is the name of a set of official documents related to police repression in Paraguay, particularly during the period of Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship. See https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/CDyA/index.htm.