Showing up in food, cosmetics, fuel, and medicine—and, by consequence, in much of the air we breathe—corn is a ubiquitous presence in our lives. Inspired by the first episode of MoMA’s Broken Nature Podcast, this text investigates how one single crop travels through our contemporary food system. Through the work of artists, academics, seed keepers, and more, curator and writer Anna Burckhardt argues that the ubiquity of corn is an example of the way in which the intangible infrastructures that surround us—made up of policy, trade routes, social networks, and behavioral codes—are intentionally designed.

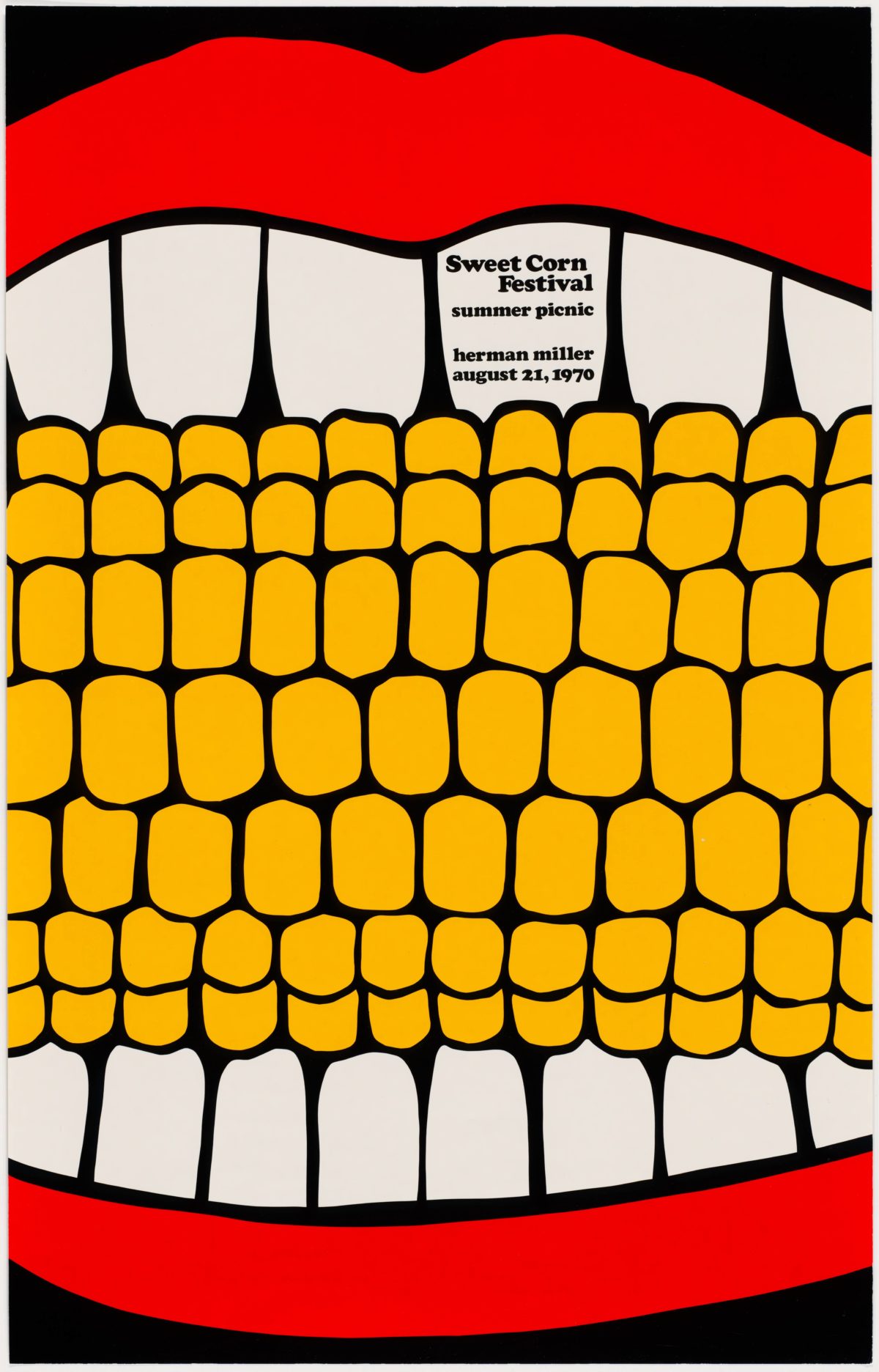

In 1970, Steven Frykholm, a recent hire of the in-house graphic department at Herman Miller, was tasked with designing a poster to advertise the furniture company’s annual summer picnic. To illustrate a quintessential institution in the United States, Frykholm employed an equally “American” symbol—one that most adults and children would recognize as the ultimate summer barbeque side dish: corn on the cob (fig. 1). His poster—with its bright colors, glossy varnish, and Pop art references—proved so successful that the company asked him to design new versions each year until 1985. But what is it about corn—which was first domesticated in Mexico—that has made it an inherent symbol of the United States? And how has this vegetable/grain, and its wholesome associations with summer picnics and fun, come to exemplify a lot of the flaws in our contemporary industrialized food systems?

Showing up in food, cosmetics, fuel, and medicine—and, by consequence, much of the air we breathe—corn is a ubiquitous presence in our lives. Even those who avoid it as part of their diet inevitably come into contact with it several times per day. The proliferation of corn has had major consequences for our health and the environment. This text looks at how this single crop travels through our contemporary food system in surprising and sometimes invasive and devastating ways, and where models might exist for new (which might mean very old) approaches. This kind of systems thinking is key to Broken Nature, the exhibition and podcast series that inspired this text. Both projects explore human ties to nature and advocate for the concept of restorative design—a vision of design that is aware of its own role in the environmental crisis and engages in making things better for humankind, other species, and the whole planet. Design plays a central role in helping citizens become more attuned to the complexity of the systems that inform our lives as individuals and as communities.

Looking at food through the lens of complex systems requires investigating the different forces that have shaped our food landscape into what we know it to be today. The ubiquity of corn, for instance, helps us understand that the intangible infrastructures that surround us—made up of policy, trade routes, legislation, social networks, behavioral codes, etc.—are also intentionally designed. “It’s literally impossible [to avoid corn] without a hermetically-sealed environment,”1Corn Allergy Girl, interview by Paola Antonelli, Broken Nature Podcast, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/542. says Bex who, living with an acute allergy to corn for several years, started a blog called Corn Allergy Girl to help those with a similar condition (fig. 2).

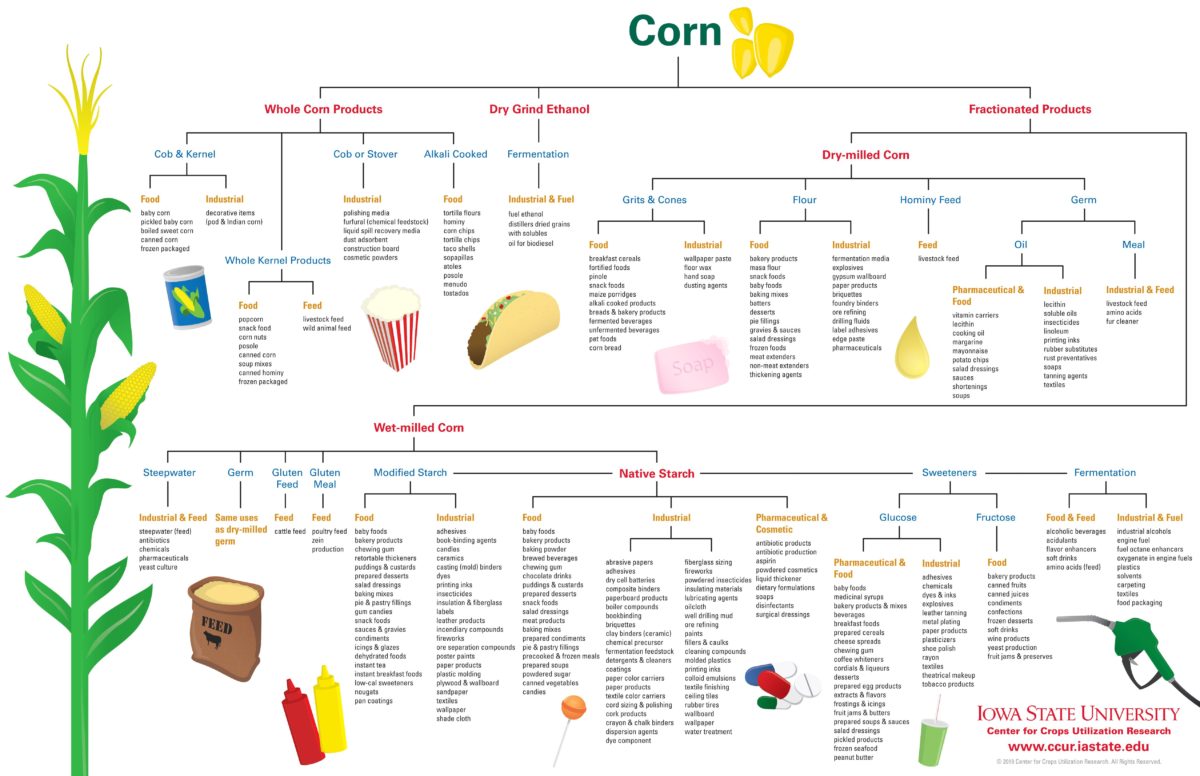

“The subtitle of my blog currently is ‘Party Like It’s 1899.’ [. . .] The safest way to live, if you’ve got this level of sensitivity to corn, is to grow everything yourself, if you can, and [to] buy things locally from people who grow things the way that you would.”2Ibid. And corn is not just something that we eat, as Bex’s blog demonstrates. It is present in hair products (shampoo and conditioner contain emollients, emulsifiers, and preservatives made from corn oil or corn dextrose, the cheapest source of fat); in the fuel that powers cars (ethanol is made from corn); and even in medicine (the most popular treatment for dehydration, for example, is dextrose IV—a corn sugar; fig. 3).3Corn Allergy Girl, “Where’s the Corn?,” Corn Allergy Girl (blog),June 2, 2013, https://cornallergygirl.com/category/tips/hidden-corn/. Corn is virtually unavoidable unless one has the means to seclude oneself, and not everyone is able to so completely modify their lives. These realities are all signs of a system that was designed with certain corporations and interest groups in mind, and not with holistic consideration for the environmental, social, and cultural well-being of all.

This didn’t happen by mistake. Humans “designed” corn thousands of years ago—originally in Mexico from a plant called teosinte—to be the versatile crop it is today.4Barbara Fraser, “Ancient DNA Reveals the Surprisingly Complex Origin Story of Corn,” Discover,December 13, 2018, https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/ancient-dna-reveals-the-surprisingly-complex-origin-story-of-corn. We have also built the infrastructures, through subsidies and free trade agreements, that allow us to give it a thousand different lives, produce it at a mass scale, and ship it all over the world, altering local ecologies. Cultural anthropologist Alyshia Gálvez is interested in the ways that food and trade policy in the United States has had profound and reverberating impacts on Mexico’s food system. “I began to see that in the last twenty-five years, there had really been a shift in how people were able to access food, what they were able to access, and the resulting health outcomes in [the] communities.”5Alyshia Galvez, interview by Paola Antonelli, Broken Nature Podcast, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/542. For more information, see Alyshia Galvez, Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies, and the Destruction of Mexico (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018).

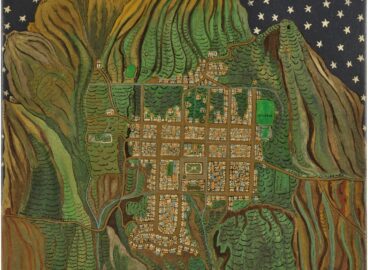

She attributes this change to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which, enacted in 1994, privileges efficiency of production over the specific needs, circumstances, and ecologies of the countries that signed it: “We [the United States] produce more corn than anybody ever wanted, and then we have to come up with all these Frankensteinian methods for getting rid of it, which includes doing new things in a chemistry lab to use the starches and sugars. But it also includes dumping it around the world and ruining the chances that small-scale producers in other countries have of selling their corn, which we could argue is real corn.” Mexican people not only invented corn, but also have made it a staple of their diets for centuries. And yet native corn—and the foods that are made from it—is becoming increasingly inaccessible as the incentives for farmers to grow it are decreasing. This is not only endangering the thousands of varieties of corn indigenous to the country, but also the bodies and health of the people for whom processed foods—made with “engineered” American yellow corn—are more easily accessible than what is grown locally. “It’s become increasingly more difficult for people to consume what we call the milpa-based diet, which is the diet based on native corn and the things that are grown with corn, like beans, chilies, and squash. Those foods, which are such a staple part of the millennial cultures of Mesoamerica going back thousands of years, are really becoming almost elite consumer goods (fig. 4).”6Galvez, interview by Antonelli.

How do we resolve this imbalance? Are there actions that we can take to resist an oppressive globalized system? Artists throughout Latin America have long explored corn’s economic, nutritional, and symbolic power within the region, and the ways in which colonial and imperialist practices might disturb bodies, ecologies, and economies. In Epitome o modo fácil de aprender el idioma Nahuatl (Epitome or Easy Method of Learning the Nahuatl Language, 1996) by Mexican artist Laura Anderson Barbata, five thousand human teeth and hair are embedded in wax in the form of a corn cob (fig. 5). While the work focuses particularly on language—each tooth represents a lost Nahuatl word—it also stresses the intricate ties between food and bodies, and underscores the ways in which corn acts as both a cultural symbol and a dietary staple.7Madeline Murphy Turner, “We, a part of them: Laura Anderson Barbata and the disassembly of border regimes,” Burlington Contemporary, issue 4: Art from Latin America (June 2021): 7.

Similarly, Alguna vez comimos maíz y pescado (We Once Ate Corn and Fish, 2012–19) by María Buenaventura’s explores two elemental traditional foods from the region of the Bogotá River around Colombia’s landlocked capital: native corn and Capitán fish. Both food sources have disappeared from the diet of the population as the city embarked on a violent process of modernization and the pollution of the river reached extreme levels. Working with a seed keeper named Fabriciano Ortiz, Buenaventura created a large-scale installation made of adobe bricks in which she displayed and honored the intricate structure of the different kinds of native corn that used to grow in the area but have progressively disappeared as yellow corn has taken over (fig. 6). Since 2006, Colombian law mandates that campesinos and agricultural producers exclusively use patented seeds, which not only benefits multinational corporations such as the Monsanto Company and DuPont,8Grupo Semillas, “Las leyes que privatizan, controlan el uso de las semillas y criminalizan las semillas criollas,” Revista Semillas, nos. 53–54 (December 2013), https://www.semillas.org.co/es/las-leyes-que-privatizan-controlan-el-uso-de-las-semillas-y-criminalizan-las-semillas-criollas. but also has led the Instituto Nacional Agropecuario, the country’s national agricultural institute, to destroy thousands of native seeds.9“El ICA destruyó semillas en todo el país,” Noticias Canal 1, September 1, 2013, https://noticias.canal1.com.co/noticias/el-ica-destruyo-semillas-en-todo-el-pais/. In this context, Buenaventura’s work highlights the revolutionary work of individuals such as Ortiz, who has dedicated his life to preserving seeds that are under constant threat by a system that protects the interests of corporations over those of individuals and regional ecologies.

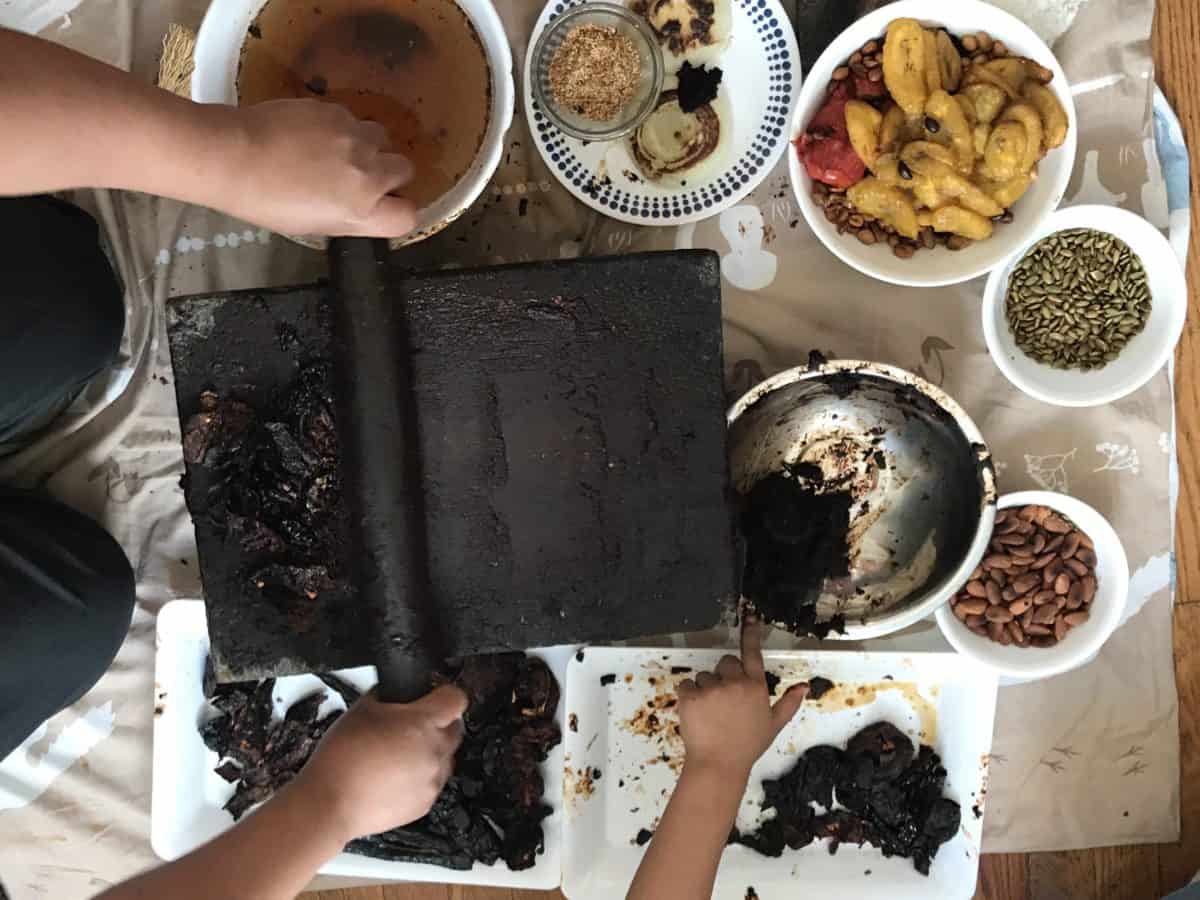

Indeed, indigenous and peasant communities are at the forefront of the fight to protect traditional foodways and practices, as community organizer Yira Vallejo notes. Vallejo serves on the executive committee of the annual Feria de la Agrobiodiversidad, a native-seed exchange that brings together more than 450 campesinos from indigenous communities across the state of Oaxaca, Mexico.10CONABIO (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y USO de la Biodiversidad), “Feria Estatal de la Agrobiodiversidad: Documento Ejecutivo para Tomadores de Decisión,” https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/corredor/pdf/PROFORCO/14-Documento-ejecutivo-tomadores-decision.pdf. She and her husband, artist Jonathan Barbieri, have also been working with filmmaker Gustavo Vazquez to produce a documentary film called Los Guardianes del Maiz (The Keepers of the Corn), which describes the deep bond between ancestral corn and the Mexican people (fig. 7). The Feria “is an event that brings together families where they exchange not only seeds, but also knowledge,” Vallejo explains. “The roots [of the event] are very old,” adds Barbieri, who continues: “For thousands of years, people have come together from one village to another in certain regions to exchange two things: knowledge and seeds. Knowledge is the culture and the methodology and everything else. The seed is the genetic packet. And by exchanging seeds and trying them out in their own different places, respective villages, the seeds themselves are in constant evolution. This is a coevolution between human beings and a grain that they invented (figs. 8, 9).”11Yira Vallejo and Jonathan Barbieri, interview by Paola Antonelli, Broken Nature Podcast, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/542.

At the center of these initiatives are the close bond that exists between humans and corn, and the understanding of the intricate threads—ecological, cultural, and social—that need to be nurtured and repaired in order to create a food system that nourishes rather than depletes. While there is no single solution to a systemic problem, seed keepers like Fernando Otriz, or the communities working with Vallejo and Barbieri, present alternative approaches that are echoed by several kindred initiatives related to native crops in other parts of the world. These endeavors are attempts to reconnect communities with their own culture and environment for the benefit of all. Some of them—rooted in an understanding of the complexity of the ties that connect us to the environment and to each other, and explored at length in a MoMA-produced podcast episode as part of the Broken Nature series—could be blueprints for national and international policy regarding agriculture, trade, and the environment.

- 1Corn Allergy Girl, interview by Paola Antonelli, Broken Nature Podcast, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/542.

- 2Ibid.

- 3Corn Allergy Girl, “Where’s the Corn?,” Corn Allergy Girl (blog),June 2, 2013, https://cornallergygirl.com/category/tips/hidden-corn/.

- 4Barbara Fraser, “Ancient DNA Reveals the Surprisingly Complex Origin Story of Corn,” Discover,December 13, 2018, https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/ancient-dna-reveals-the-surprisingly-complex-origin-story-of-corn.

- 5Alyshia Galvez, interview by Paola Antonelli, Broken Nature Podcast, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/542. For more information, see Alyshia Galvez, Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies, and the Destruction of Mexico (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018).

- 6Galvez, interview by Antonelli.

- 7Madeline Murphy Turner, “We, a part of them: Laura Anderson Barbata and the disassembly of border regimes,” Burlington Contemporary, issue 4: Art from Latin America (June 2021): 7.

- 8Grupo Semillas, “Las leyes que privatizan, controlan el uso de las semillas y criminalizan las semillas criollas,” Revista Semillas, nos. 53–54 (December 2013), https://www.semillas.org.co/es/las-leyes-que-privatizan-controlan-el-uso-de-las-semillas-y-criminalizan-las-semillas-criollas.

- 9“El ICA destruyó semillas en todo el país,” Noticias Canal 1, September 1, 2013, https://noticias.canal1.com.co/noticias/el-ica-destruyo-semillas-en-todo-el-pais/.

- 10CONABIO (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y USO de la Biodiversidad), “Feria Estatal de la Agrobiodiversidad: Documento Ejecutivo para Tomadores de Decisión,” https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/corredor/pdf/PROFORCO/14-Documento-ejecutivo-tomadores-decision.pdf.

- 11Yira Vallejo and Jonathan Barbieri, interview by Paola Antonelli, Broken Nature Podcast, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/542.