Taking as her point of departure the kiondo, and the acknowledgment of the multiple forms technology can take, South African based curator and art historian Portia Malatjie discusses Wangechi Mutu’s generative re-imagination and re-inscription of the foundational figure of Eve, gathered together in an untitled portfolio of five etchings and three aquatints. This commissioned feature is part of One Work, Many Voices, a series of texts and insights into works in the MoMA collection.

“Technologies of Everyday Innovation”

In Transient Workspaces: Technologies of Everyday Innovation in Zimbabwe, Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga compels us to consider different forms of technological innovation and intervention.1Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, Transient Workspaces: Technologies of Everyday Innovation in Zimbabwe (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014). He invites us to acknowledge the multiple forms that technology can take, and proposes that we not only think of them in relation to their western-centric forms. What is central to Mavhunga is thinking about forms of mobility, ones that are specific to hunting, as means of inventing, implementing, and benefiting from technology. Similarly, Edward Shizha expands ideas about indigenous African technologies to incorporate “techniques used in the production of arts and crafts, blacksmithing, iron smelting, carding and weaving.”2Edward Shizha, “African Indigeneous Perspectives on Technology,” in African Indigenous Knowledge and the Sciences: Journeys into the Past and Present, eds. Gloria Emeagwali and Edward Shizha (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2016), 47.

As an extension to broadening the criteria for what we consider technological innovation, we might think about the kiondo, a well-known kind of basket made by the Kikuyu people of Kenya,3The Kikuyu people are one of the ethnic groups in Kenya. as a form of technology. At the nexus of the kiondo is the mukonyo, the preliminary circular component that acts as a foundation for the rest of the basket. The strength or feebleness of the mukonyo—which also refers to the navel, or that which connects a child to its mother through the umbilical cord, while cultivating and sustaining life during the period of gestation—will determine the success of the kiondo, attesting to the necessity of grounded origins.4If one were to think about the story of Genesis in the Bible, one would conclude that neither Eve nor Adam had navels. Their gestation was outside the parameters of normative human formation, having never been conceived or birthed in what we know to be the biological way. Instead conception and development in the womb, the pair are themselves considered sources of life. Further, as Joseph Waweru Kamenju posits, the kiondo is a kind of language full of codes, significance, and philosophies.5Joseph Wareru Kamenju, “The Kikuyu Kiondo Kosmology and Architecture: Why Traditional African Huts Are Circular” (paper presented at the East Africa Transition: Ethnicity, Economy and Environment Symposium, Nairobi, June 13, 2002), https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/primordial/Kikuyu-Kiondo-Cosmology.pdf. He argues that it is “one of the most powerful symbols among the Kikuyu,” and initiates the possibility of theorizing the basket as a doctrine that governs most of Kikuyu culture, from its architecture to its myth-making and children’s play activities.6Ibid.

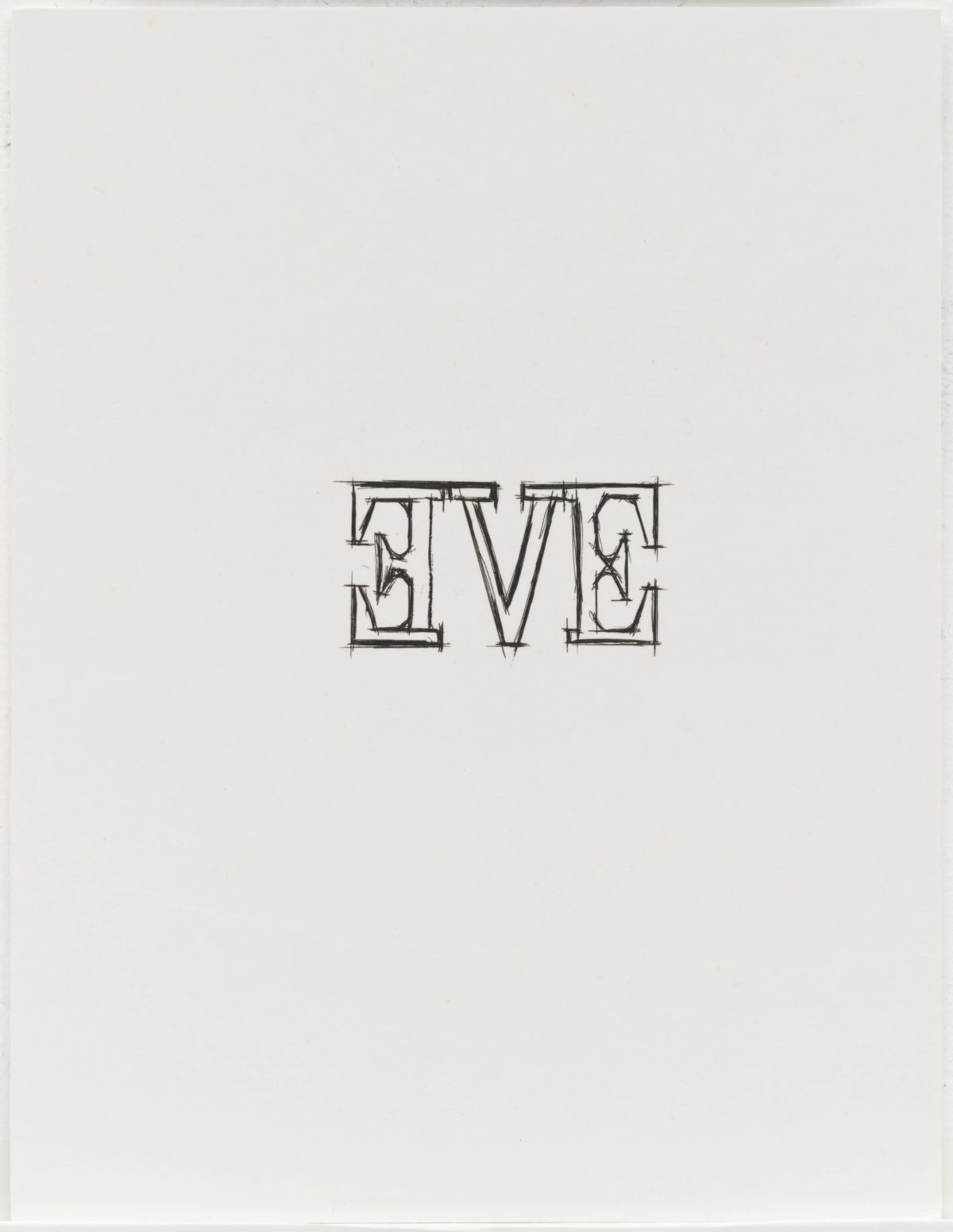

Kenyan-born artist Wangechi Mutu (born 1972) refers to the symbolism of the mukonyo and the importance it has in Kenyan culture.7Personal communication with author, 2021. She recalls and notes its generative capacity, making a link between its artistry, social and political significance, and relationship to notions of origins and grounded-ness. Mutu’s meditation on the mukonyo can be seen as the consolidation of her thinking around the series Untitled from Eve (2006), which is a deliberation on the representation of women, technology, and the potential for reimagination and re-inscription. Untitled from Eve, a series of five etchings and three aquatints printed at master printer Jacob Samuel’s workshop in Santa Monica, California, employs etching, monograph, collage, aquatint, and drawing, and is inspired by the figure of Eve. It considers the excessive and obsessive representations of ‘the first woman on Earth’, which, while varied, are often harmful and emblematic of hetero-patriarchal anxieties and injustice. Throughout history, Eve has been portrayed as the originator of sin, a wicked transgressor, and a seductress, among other representations. By reflecting on her, Mutu continues her own fascination with female anatomy, inscription and legibility, seemingly femininized symbolism, and the role of women in history.

Mechanizations and Delicate Mark-Making

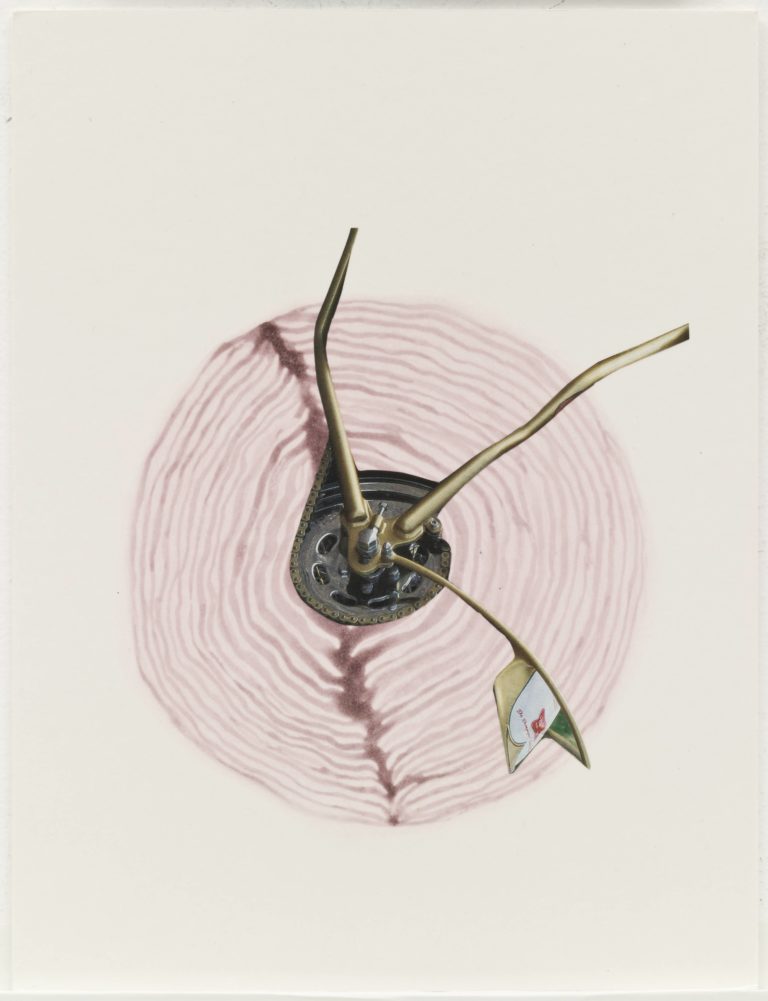

Mutu’s recourse to the intersections between gender and technology—often discussed in relation to cyborgism and Afrofuturism—has been notable throughout her practice. In collages such as In Killing Fields Sweet Butterfly Ascend (2003), the recognizable hybrid of women’s bodies and machinery, often in the form of motorbikes, is used to contemplate physical trauma inscribed on women’s bodies. Mutu’s chimeric figures often “adopt mechanical prostheses” and are meditations on the mechanization of the body that is perceived and inscribed as other (fig. 2).8Merrily Kerr, “Extreme Makeovers,” Art on Paper 8, no. 6 (July/August 2004): 29. She continues to merge parts of the human form (or its metaphors) with technological components. The relationship between women and technology, often employed in the field of advertising, where women’s bodies are used to sell technological objects, is one that requires scrutiny and change. There is a need to rethink the role of women’s bodies as extensions of machines, or inspiration for technological intervention.

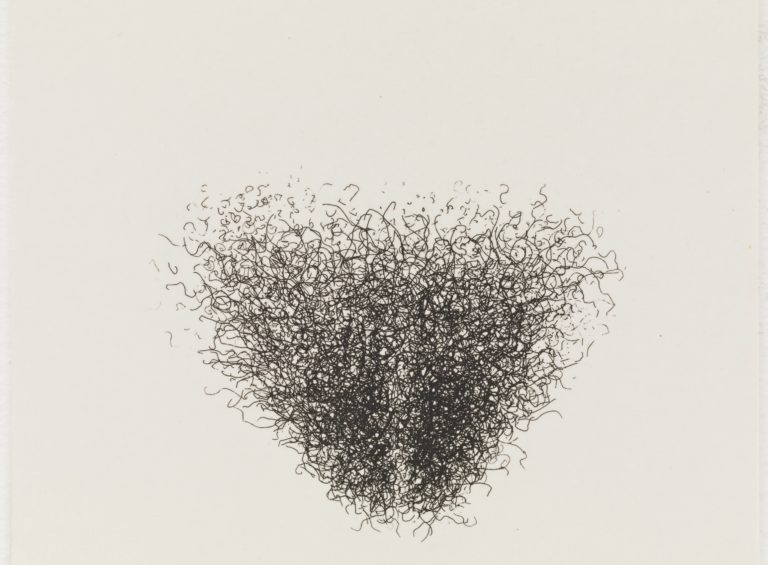

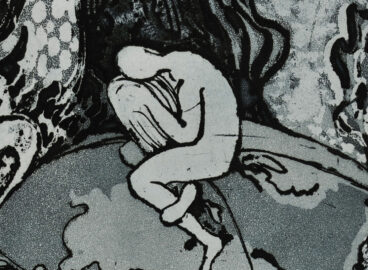

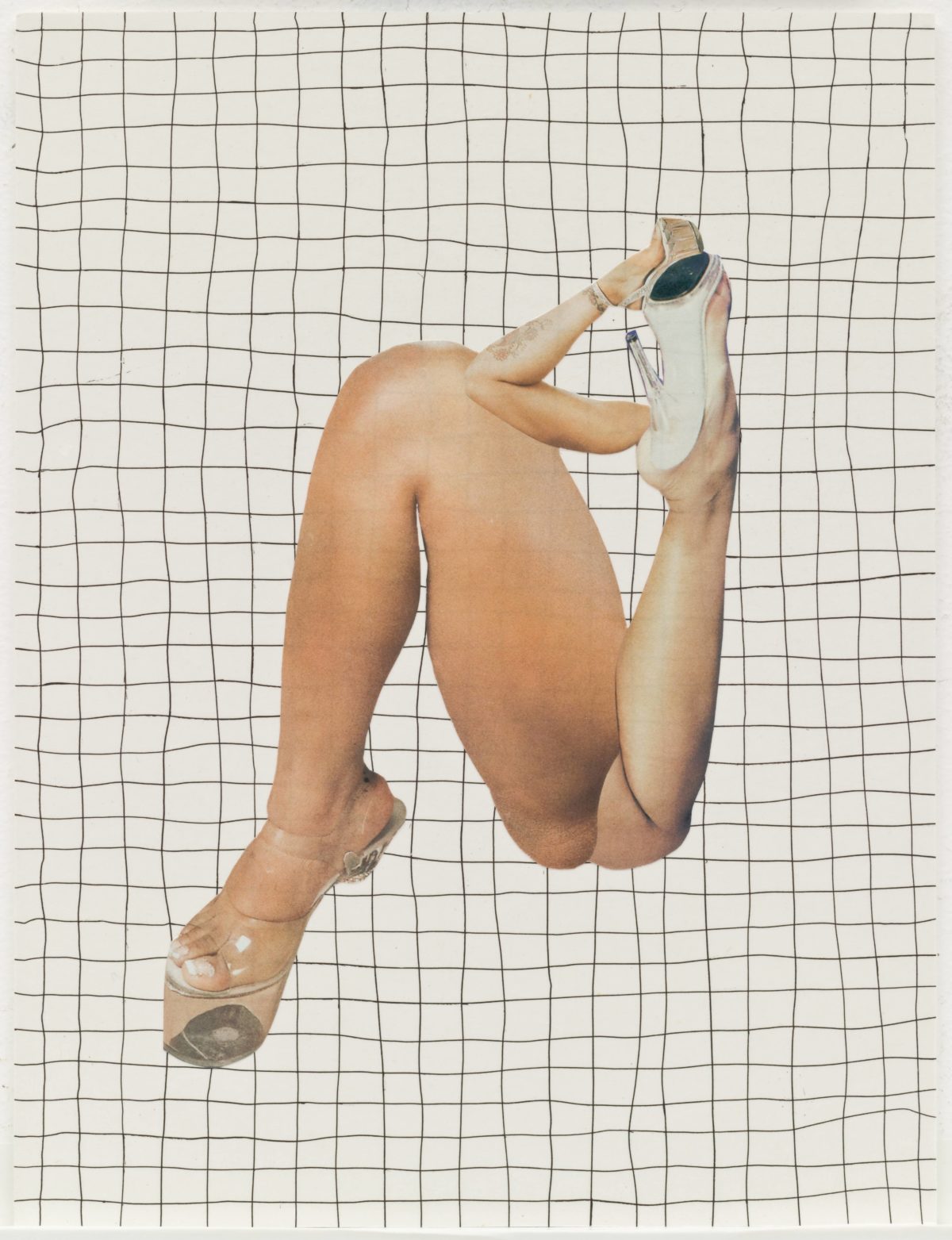

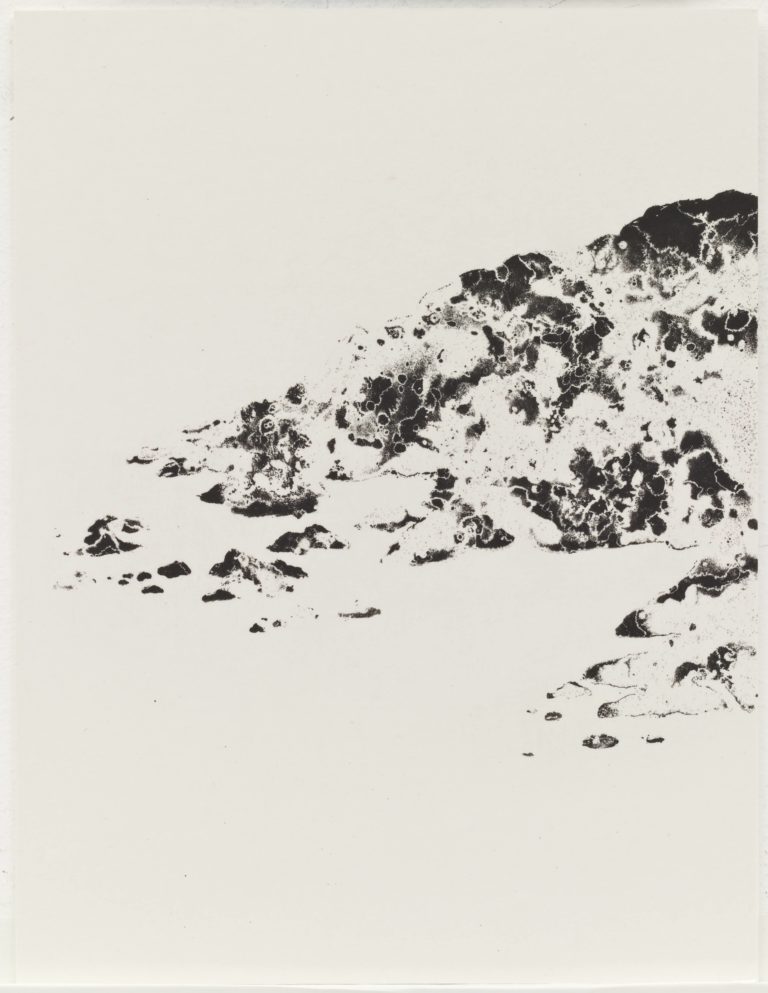

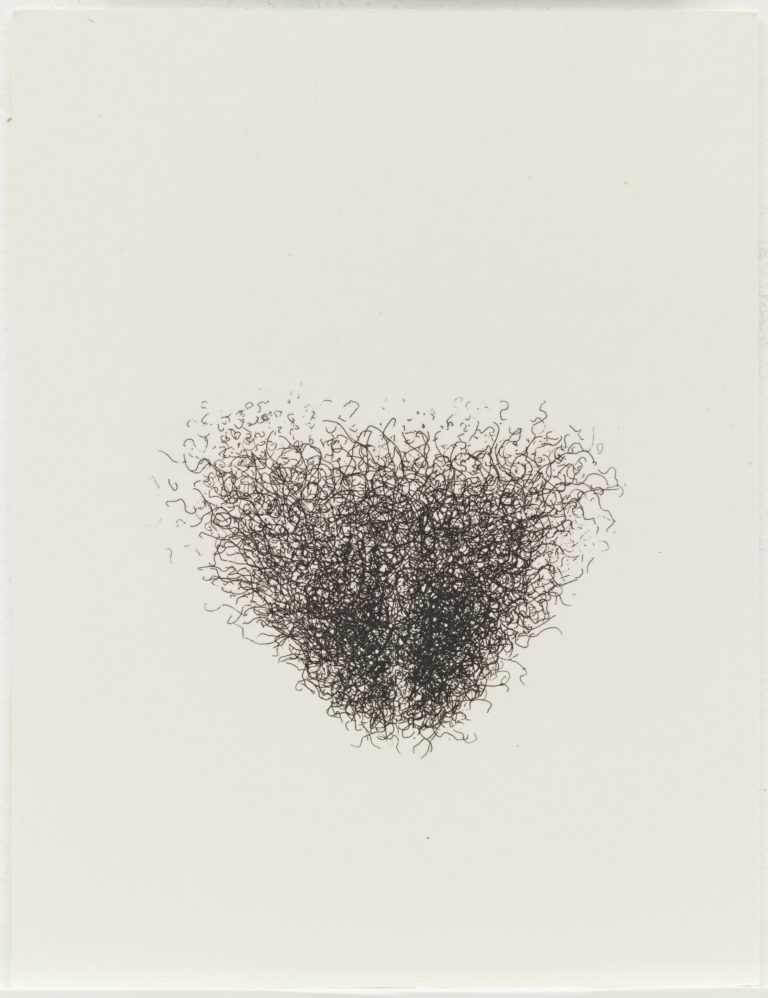

Untitled from Eve is punctuated by a variety of exercises in artistic sensibilities. Mutu invites us to think about the sensitivity and care it might take to offer more positive imagery of womanhood, from the manner in which Eve’s name is inscribed on paper (fig. 1), to the sensitivity of visual form and its relationship to negative space (fig. 3). She motions toward what it would mean to delicately approach an image of a woman’s pubic area (fig. 4), and in so doing, to refuse any damaging connotations. The recognizability of the drawing (fig. 4) as a depiction of a woman’s short and curly pubic hair sits appositionally to the abundance of phallic representations and aesthetics permeating the visual arts. Mutu seeks to present this part of a woman’s anatomy as delicate and unapologetically present. Despite its obviousness, or maybe because of it, she makes sure to depict an image that might be read as confrontational and antagonistic in a sensitive, beautiful, serene, and mesmerizing manner. The issue of delicacy is intentional. The artist pauses on the act of drawing, thinking of it as a central activity, and one that occurs as a series of “subtle, calming, contemplative movements.”9Personal communication with author, 2021. This slowing down and contemplation—punctuated by the “unfilled” negative space within the picture plane—are presented as an abundant “monotonous delicacy.”10Ibid.

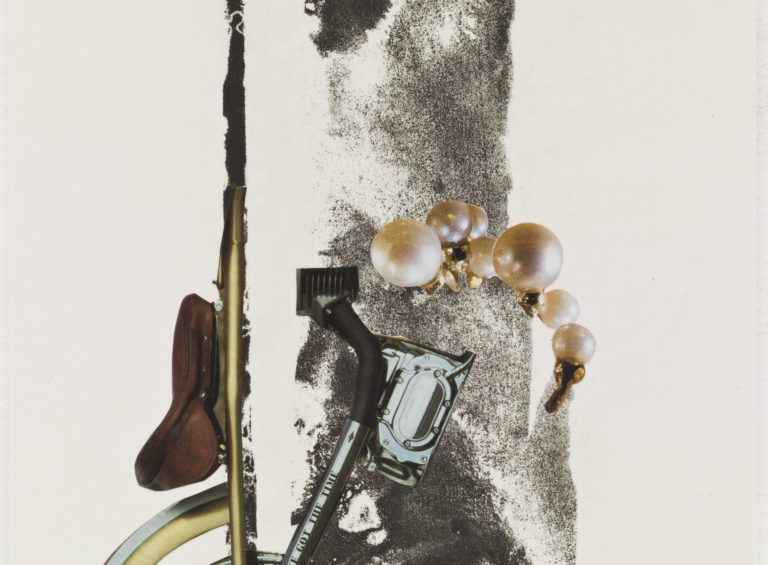

This sensitivity and delicateness are sometimes dislodged and disrupted by Mutu (fig. 2). The artist abandons the grace and fragility of the rest of the works by presenting an image that is “almost vulgar in its obviousness.”11Ibid. Here, the issue of origins is provided as a tension, with the distorted and collaged images extricating their original and intended purpose. The jarring imagery of the legs, which sit uncomfortably against the technology of a regulating anthropometric grid, questions the manipulation of selling bodies—women’s bodies, in particular. The viewer cannot help but investigate the image, wilfully seeking to make sense of it. The content of the work—a woman in a pose suggestive of exotic dancing, in high heels with her legs contorted in an evocative fashion—presents like an endless question mark. The grid, as a scientific apparatus and equalizer of race, gender, sexuality, and womanhood, accentuates the problematic control of women’s bodies throughout history. The body that is controlled here refuses total domination—and by virtue of its distortion, which has been potentiated through the technology of printmaking and collage, demands to be seen differently, and insists on evading capture and entrapment within the grid.

What consolidates Untitled from Eve is Mutu’s love for drawing, and the admirable care she pays to her medium. She summons the power of mark-making and inscription to articulate the historically labored treatment of the representation of women. In producing these images, she intended to arrive at what she calls “a feminine print.”12Ibid. While thinking about the female body and the connotations that have befallen it throughout history, the artist manifests the female touch in print. She recalls, with affection, how the act of printmaking, and the supplementary acts of drawing and collage, were for her a rewarding process. The act of pondering each mark with care and precision, ensuring that each one reflects its deliberate and considered execution, is apparent in the measured treatment of each individual works in the series. Mutu uses these specific mark-making techniques to help us think about fragility, grace, origin, control, (mis)representation, and transgression—all through the ubiquitous figure of Eve.

Proposition for Generative Technologies

Mutu centers the image of Eve as a repository for women’s history. She ruminates on this image as one that was invented and coded in hetero-patriarchal laboratories, in spaces that Ruha Benjamin might call “tech fixes [that] hide, speed up, and even deepen discrimination.”13Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 9. She pays attention to the loaded-ness of such coding, and offers forms of generative decoding and re-presentation. Acknowledging that “[t]here is a tendency to look at Africa as if it never possessed any science and technology before Europeans set foot on the continent,” Edward Shizha shows us that “Africa created its own indigenous technology using its own scientific knowledge.”14Shizha argues that “each African society, from the East to the West and from the North to the South, had its own scientific knowledge, which was put into practice and worked for the good of its people. The tools with which societies worked and the manner in which they organized their labour are both indices of social and technological development. . . . Pre-colonial Africa had scientific and technological tools that were designed and used to enhance the quality of lives of indigenous people in African communities. There were traditional skills and techniques that were used in the production of arts and crafts, blacksmithing, iron smelting, carding and weaving, and brewing, among others that summed up indigenous technology in Africa.” Shizha, “African Indigeneous Perspectives on Technology,” 47. Echoing the sentiment, Mavhunga states that “African history is replete with examples of people adjusting their traditions to craft self-help solutions to everyday challenges and to selectively tap into resources from outside.”15Mavhunga, Transient Workspaces, 7.

With this in mind, it is possible to consider Mutu’s recourse to the technology of the mukonyo as an amalgamation of African traditional and indigenous forms of technology, alongside more contemporary and western-orientated accounts. In addition to the more mechanical, “Western(-originated) high-tech exemplars”16Ibid., 19. that epitomize Mutu’s practice (figs. 5, 6), there is the opportunity to read Untitled from Eve as a form of leaning into what Mavhunga calls “technologies of everyday inventions.”17Ibid., 7. We might see a signaling to the technology of the mukonyo as an extended attribute of Mutu’s interest in technological intervention—and its detriment to women, their representation, and their bodies. However, the technology of the mukonyo offers a different reading and use of technology and women’s bodies and work, and considers the kiondo and its nexus as spaces for women to gather and form communities. Through this community work potentiated by collective indigenous technological practices, such as those expressed by Shizha and Mavhunga, the solitary figure of Eve is no longer in isolation, but rather communes with more generative and positive images of woman able to hold and support her. Drawing a parallel between technology and mobility, Mavhunga argues that “technology is a way of doing.”18Ibid., 17. This potentiates acts of undoing as forms of radical action, and by extension, we can consider Mutu’s undoing of problematic representations of Eve as an engagement with technology. As Ruha Benjamin states, “It is time to reimagine what is possible. So let’s get to work.”19Benjamin, Race After Technology, 2. Mutu’s representation of Eve and the undoing of the damaging imagery associated with her become forms of uncoding and decolonial praxes through technological intervention rooted in epistemic disobedience.

- 1Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, Transient Workspaces: Technologies of Everyday Innovation in Zimbabwe (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014).

- 2Edward Shizha, “African Indigeneous Perspectives on Technology,” in African Indigenous Knowledge and the Sciences: Journeys into the Past and Present, eds. Gloria Emeagwali and Edward Shizha (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2016), 47.

- 3The Kikuyu people are one of the ethnic groups in Kenya.

- 4If one were to think about the story of Genesis in the Bible, one would conclude that neither Eve nor Adam had navels. Their gestation was outside the parameters of normative human formation, having never been conceived or birthed in what we know to be the biological way. Instead conception and development in the womb, the pair are themselves considered sources of life.

- 5Joseph Wareru Kamenju, “The Kikuyu Kiondo Kosmology and Architecture: Why Traditional African Huts Are Circular” (paper presented at the East Africa Transition: Ethnicity, Economy and Environment Symposium, Nairobi, June 13, 2002), https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/primordial/Kikuyu-Kiondo-Cosmology.pdf.

- 6Ibid.

- 7Personal communication with author, 2021.

- 8Merrily Kerr, “Extreme Makeovers,” Art on Paper 8, no. 6 (July/August 2004): 29.

- 9Personal communication with author, 2021.

- 10Ibid.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Ibid.

- 13Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 9.

- 14Shizha argues that “each African society, from the East to the West and from the North to the South, had its own scientific knowledge, which was put into practice and worked for the good of its people. The tools with which societies worked and the manner in which they organized their labour are both indices of social and technological development. . . . Pre-colonial Africa had scientific and technological tools that were designed and used to enhance the quality of lives of indigenous people in African communities. There were traditional skills and techniques that were used in the production of arts and crafts, blacksmithing, iron smelting, carding and weaving, and brewing, among others that summed up indigenous technology in Africa.” Shizha, “African Indigeneous Perspectives on Technology,” 47.

- 15Mavhunga, Transient Workspaces, 7.

- 16Ibid., 19.

- 17Ibid., 7.

- 18Ibid., 17.

- 19Benjamin, Race After Technology, 2.