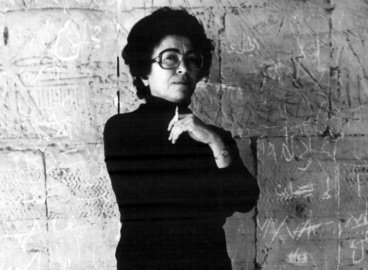

In 2007, at age twenty-seven, having already spent several years directing and editing audiovisual programs for broadcast, Rosine Mbakam (born 1980) left her native Cameroon to attend film school in Belgium. She reflected on her experience when we met over video earlier this year to record a conversation coinciding with the launch of her newest film Delphine’s Prayers (2021). The reigning idea was one of unlearning. To come into her own as a filmmaker meant to reverse engineer training in the West, where pursuit of directorial authority leaves room for little else; we recalled how violent the language of cinema is: to point, to shoot, “cut!” and so forth.

With great lucidity and warmth, Mbakam spoke about Delphine’s Prayers, the third entry in her nonfiction triptych devoted to telling the stories of West African women across generations and geographies (viewable July 6–20 on Virtual Cinema). She is an indispensable contemporary voice in the realm of decolonial approaches to cinema, and is at work on a collaborative project exploring how moving-image technology has been built to construct and propagate whiteness. But above all, Mbakam was quick to remind me that her work is in dialogue with the great generation of African cinema pioneers: Ousmane Sembène (Senegalese, 1923–2007), Djibril Diop Mambety (Senegalese, 1945–1998), and Jean-Pierre Dikongue Pipa (Cameroonian, born 1940), and relayed with great excitement plans to show the film in Cameroon—especially in settings such as schools where Delphine’s story could connect with young women and girls. Our conversation, recorded on March 23 as part of the premiere of Delphine’s Prayers at Doc Fortnight 2021, has been condensed and edited for post.

Delphine’s Prayers is the first film I shot after film school, but it’s being released as my third feature. I met Delphine twelve years ago when I came to Europe to study cinema. We were connected by a mutual acquaintance as fellow Cameroonians who had recently arrived in Brussels, and we became friends. After five years at INSAS (Institut national supérieur des arts du spectacle et des techniques de diffusion de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles), she introduced me to Sabine, who became the subject of Chez Jolie Coiffure (2019), when I became interested in making a film in the shopping center nearby. As I was preparing to shoot Chez Jolie Coiffure, Delphine asked me to make a film about her first. I was a little bit surprised, telling her, “You are my friend. I don’t want to make a film about your life.” But she replied, “You don’t know anything about my life.” Two days later, we began filming, and she started telling me her story.

In film school, you learn that you have to know the story you want to tell, that you have to go through all kinds of preparations in order to make a film. But experience has shown me that sometimes, you have to abandon preparations and take what life gives you. And that’s what I experienced with Delphine. Had I waited and gone through the motions of planning before starting, had I been there with a crew, I would not have the same story. I would not have this spontaneous outpouring. And the film is also the film of the moment—of that moment in particular, when Delphine was moved to speak about what she had been through—and not a later date in accordance with a production schedule. I had to respect the moment. I hope one senses that in the film.

As African filmmakers studying in Belgium, we are taught Western cinema. I’ve had to deconstruct this to find my own cinema, because the way cinema is made in the West is not my way of doing cinema. It’s not the same reality. If I take the Western approach to making movies, I will destroy the singularity of the story that I want to film. I have to find, each time, the right way of filming the situation, story, or subject at hand. We even joked about it: Delphine asks me if I’m ready, if I have my “carnet de bord,” my logbook. And at the start of the film, she is the one directing me to sit next to her—rather than me occupying this other kind of position behind the camera. The mise-en-scène mirrors our friendship. It was similar with Sabine. She asked me in the first scene to enter the salon, to physically be a part of her world with my camera, not to film it from the outside. Sabine knows her space better than I do, she knows her story better than I do . . . and, as a filmmaker, I have to respect that. If I want to tell Sabine’s story, or Delphine’s story, I have to respect their gaze and what they have asked me to do.

I filmed Delphine at home for ten days. It wasn’t really a question of directing. Delphine knew exactly what she wanted to tell me and the way in which she wanted to say it. Throughout, I questioned my own role and place. I didn’t want to assert power over her story; I wanted to just be silent and listen, and to ensure that she was comfortable. Quickly, the bed became the focal point of our sessions. That was the place of confidence for her, where she was at ease and sheltered from the outside world— not least from her husband and children, who were on the other side of the apartment. Usually we say that the director has the final word, but with Delphine, after ten days, the shoot ended as suddenly as it had started. One day I showed up with my camera, we talked for a little bit, and she told me that she’d said everything there was to say. No planning, the film shoot was over.

I did a first edit in 2015 and it wasn’t right. At that time, I was carrying around a kind of rage, born of my situation here, by my experience as a lone Black filmmaker in the film school, and I edited that film with my anger. I can say that. And it was not the story of Delphine, but rather the story of my bitterness. But that is not the kind of work I want to make, and so I set the footage aside and started working on a project about my mother, which would become Two Faces of a Bamiléké Woman (2016). It was only in 2019 that I felt I was ready to edit the film. The experience of Chez Jolie Coiffure and Two Faces gave me the maturity to see Delphine’s story in the right way. When I started the editing, the choice of sequences and the process was really simple because the moment was right. I was no longer seeing Delphine through my lived experiences, but just seeing her as she was and is and . . . and everything was evident to me and to the editor. After editing, I asked Delphine to come and watch the film, and she saw it and told me, “I want people to see it now.” For me, this was a huge relief as I wanted to respect her voice and testimony.

The coda, when I appear on-screen, also changed. I didn’t want to speak for Delphine or take her story as my own, because we don’t have the same story. The difficulty was to find the right words for that moment. I think I may have succeeded in doing that. I don’t know. I was deeply shocked by her story: it was everything I wanted to question about my culture in Cameroon, and here, in Europe. Over the course of my films, I have been thinking about the colonialist gaze in Africa and on African women and girls. This starts with my mother, who lived through the colonial period in Cameroon and the war of independence. For my generation—after independence, we’re supposed to be in a postcolonial period, right? But, of course, colonialism has not gone away; it just has taken another shape. I want to call attention to the forms of coloniality that we’ve encountered on our journeys—Delphine, Sabine, and me—each in our own way.

At the moment, I am at work on Prism, a collective project with An van Dienderen and Eléonore Yameogo and we are working on how the camera was created to film white skin. For me, this has been an opportunity to explore not just the technology, but also the surrounding ideologies that have created our current system. As an African filmmaker, it’s the opportunity to talk about the colonization of my cinematic gaze as a filmmaker. How, as a filmmaker, I have to film people, knowing that the camera, which is my main tool, is not designed to my advantage. How filmmaking was taught to me. My own deconstruction of the art form’s power relations, colonial relations, gender relations. Actually, it all started with a film made by Raymond Depardon in the 1990s that was filmed across the African continent. When I saw it, I discovered the way the world was seeing people like me. For me, right then, a shift took place. I came to see that we as Africans never have a choice: the choice of our story, the choice of our social situation. And, at that moment, I decided that I have to have the choice of the cinema that I want to do and the way I want to do it. And, yes, my work is questioning that.