To uncomplicatedly enunciate and hyphenate the manifold concentrations of Daniel Lie’s practice would be to miss the artist’s durational engagement with their complexities. Intimately coiled, these lifelong preoccupations are at the heart of the artist’s experience of the world. This conversation with Lie is the second commission in an editorial series initiated by the C-MAP Asia Fellow. The debut text was written by Tamarra.

Wong Binghao: Daniel, in one of our previous conversations, you mentioned that art can be a “queer line that connects many fields of knowledge.” This statement really resonated with me. What I enjoy about your practice is that you suture different communities, contexts, and actors—from what you call “other-than-humans” like fungi and bacteria to your family history in 1950s Indonesia. What have you gained or learned from this constellational practice?

Daniel Lie: When I spoke about this queer line (queer as a constantly transmuting way of being), I was thinking of art as a learning device that can be related to other fields of knowledge. All of my works are complex and require extensive outreach to people from diverse fields of action and research in order for me to fully understand the perspectives of a topic or concept I am exploring. In these (dis)encounters, open-ended partnerships can be forged on our journey of living and being.

For instance, in my practice I am broadly interested in the philosophical, scientific, and spiritual aspects of death. This communication and collaboration with many humans and beyond-humans are manifestations of my desire to learn from diverse views. I seek a multilayer relationship with various forms of life, as I recognize their profound importance.

In this regard, I am interested in the correlation between micro- and macrostructures, and in moving between smallness and largeness. For instance, a closeup image of a rotting fruit can look similar to a wide aerial view of a forest. Cohabiting with microorganisms can tell us a lot about how other ecosystems function. By comparison, I find that there are many restraints and limitations in terms of human society as an ecosystem—for example, in the culturally political and ideological ways in which we consider and create kinships.

As an artist who develops and is driven by research, I experience a wide range of encounters—from within the academy to non-hegemonic and nontraditional educational environments. Queerness allows for a diversion when there are boundaries to access or it deepens expertise in a particular field. For me, the queer line is very much about the possibility of existing in the in-between.

Although delving deeper into a particular topic can create greater resonances, this intensive process can also generate uncomfortable tensions and realizations. For instance, while undertaking site-specific research for my solo exhibition The Negative Years (2019) at Jupiter Artland in Scotland, I visited one of the largest farms cultivating the edible mushrooms commonly sold in European supermarkets. These mushrooms are grown indoors in large, climate-controlled hangars. At a particular point in the growth period, the environmental temperature is intentionally and significantly decreased. The fungi reacts to this menace to their existence by reproducing and generating at an increased speed. I was intrigued by this reaction to planned trauma in the cultivation of an organic species, and drew connections to the way that capitalism in human society induces and demands productivity to the point of exploitation.

WBH: To build on my previous question, how has nonbinary/trans life and thought figured in your practice? I appreciate that it is never just a matter of literal, one-dimensional representation for you.

DL: I identify with nonbinary-ness because it denies any concrete value. I think it not only is connected to gender, but also goes beyond it. My personal experiences have shown me that the binaries and boundaries of identity—like the dualities of life and death, light and darkness, man and woman, good and evil, and so on—are limiting and restraining. Hegemonic society (Western, human-centric, cis-hetero-white-nationalist supremacy) needs to maintain these dualistic structures so that it can continue to classify, separate, and maintain its hierarchy. But this system does not contemplate the realities of the ecosystem. Even in talking about gender, there are so many identities and expressions of subjectivity. We live in a world that needs diversity for its sustenance.

Going back to my interest in death—it is not only witnessed in the absence of life, but in many moments of the living as well. It is an energy that moves in order for life to happen. For instance, in the phases of life, a child needs to symbolically die in order for the teenager, and subsequently the adult, to come into being. One is contained within the other. In this sense, the binary perspective of life and death has a restrictive notion of beginning and end that diminishes possibilities of existence.

When organic matter rots, it is not dead, as people commonly believe, but rather filled with the presence of many living beings and decomposers—with fungi, bacteria, and insects. It is full of life. Abjectification is a key process of renewal. So why do we think that rotting matter is dead when the reality is actually quite the opposite? In the process of cohabitating with decay, I came to understand it as a powerful and disruptive element. I find rottenness to be nonbinary: it shows us that there is, in fact, no end or beginning in life or death.

As with my other projects, I arrived at this perception after an extended period of slow research. The passage of time has been an important actor and conceptual pillar in my works since 2014, and I have deepened my knowledge and insights on the subject with each artwork and installation that I have presented.

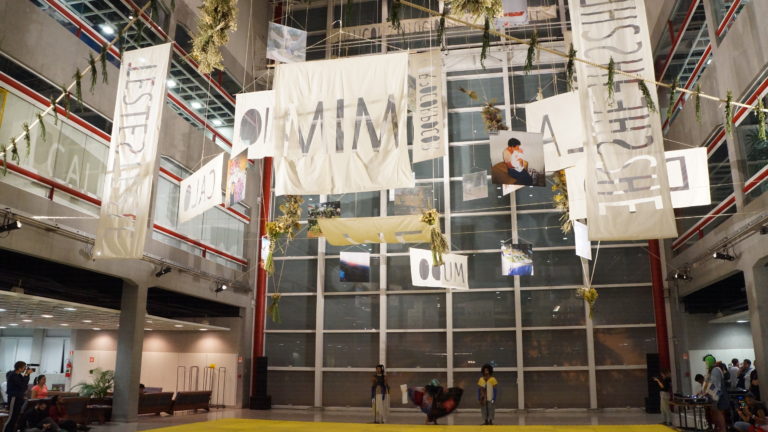

Since the start of 2021, I have been developing works under the framework of The Rotten Research. This project includes a series of site- and language-specific creations: essays; other publications; a forthcoming solo exhibition, primarily of drawings, that should open in mid-2021 at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien; and public installations at Berlinische Galerie and around the city of Berlin. The main component of The Rotten Research is a digital project titled Rotten TV: an online broadcasting and research platform that brings together creatives, thinkers, and cultural institutions from Indonesia (Cemeti—Institute for Arts and Society), Brazil (Casa do Povo) and the UK (Jupiter Artland) to progressively investigate the topic of rottenness from April to November 2021, culminating in and coinciding with the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), which will be held in November in Glasgow.

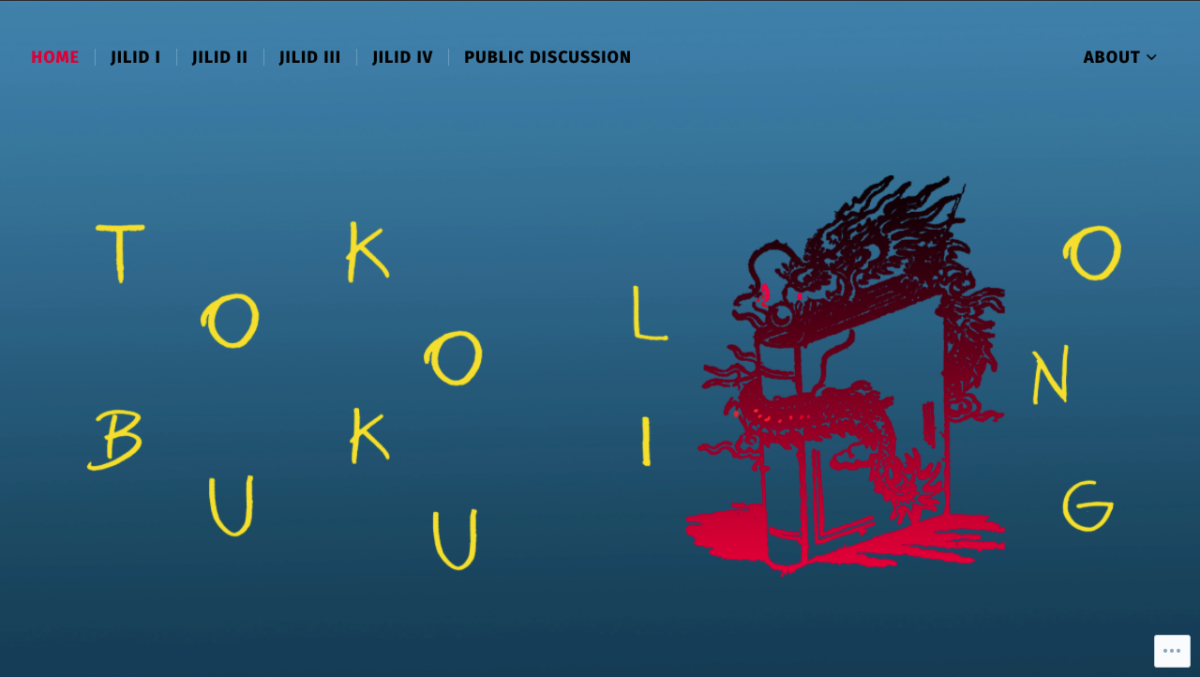

WBH: Let’s speak more about the binary of life and death. In a text titled “Walk Along ONG,”which you wrote for an incredibly detailed web-based, multiform project Toko Buku Liong (Liong Bookstore), co-created with Adelina Luft (2020), you imagine revisiting Indonesia with your deceased grandmother, Ong King Nio, sixty years after your family migrated to Brazil. In relation to these real and speculative migrations, you describe feeling like a “forever stranger.” Could you elaborate on the negotiation of place(lessness) and how it might present itself in your practice?

DL: What is life? What is death? Where do we come from? What am I doing right here, right now? These questions are ontological and can sometimes be considered cliché if they are looked at from a shallow perspective. For me they are a starting point from which to dive into complexity.

In an attempt to nurture this complexity, I went to Indonesia and lived there for about fourteen months in 2019–20. I learned the language and took traditional dance classes at the Indonesian Art Institute of Yogyakarta as a way of familiarizing myself with a nonverbal expression based on secular movements. I could not have fed this root of my life and history in Brazil. Once I was in Indonesia, I started to understand many other layers of my story. While searching for a “source,” I realized that there was never a place to “arrive.” Origin does not exist.

The more I learned about myself and my ancestors, the wider the narrative became. There was not a single point of curiosity. It was the opposite—many more branches sprouted from my initial point of inquiry. As a queer child born in São Paulo to a migrant mother from Pernambuco (Northeast Brazil) and an immigrant father from Java (Central Indonesia), I felt displaced from an early age, like I was already born in a foreign context. The creation of national mythologies in order to belong to a political situation can be reductive. I felt like such norms did not apply to me; they rejected me, as I rejected them.

I see all of us as organisms that are part of a larger ecosystem called Earth. What are the possibilities for me to relate to this planetary, ecological community? What types of negotiations are needed? Our existence is contingent upon a diversity of other existences. I am thinking here of the “other-than-humans”—of micro- and macroorganisms, quingdoms,1“Quing” is a neologistic combination of the words “queen” and “king,” alluding to a nonbinary and non-deterministic take on gender. spirits, etc. These groups make the conditions for a here and now that we experience as a version of reality. The process of question-making that I have engaged in within my practice is powered by ways of relating with these “other-than-humans” that teach and give me agency.

Madeline Murphy Turner: Daniel, could you speak more to your compelling point about the importance of living with microorganisms and what this can reveal to us about ecosystems? Given the increasing urgency and apathy toward the climate crisis in Brazil, how do you see your practice converging with dialogues regarding ecological issues in the country or region?

DL: The first layer of the ecological system that we deal with is our own body. The many ways that this body will perish and disintegrate into smaller pieces represent, for me, the transition from human whole to environmental part. When we decompose, we become soil, and when we are cremated, we become part of the atmosphere. In each case, there is a significant degree of transformation and expansion. In my practice, I consider how these separations between body and environment can be abolished. Perhaps the first step is acknowledging that humans are not and cannot engage in a hierarchical relationship with other beings. This acceptance requires a process of unlearning.

I have been cohabiting with microorganisms through a simple and daily practice that relates to my research on rottenness. Where I currently live, I have left a plate of fruits and vegetables to rot, decompose, and putrefy, thus revealing several activities: maggots and flies appear, mold grows and takes over the surface, and food liquefies and/or dries out. In this process, I witness small yet intense changes that debunk the symbolic connection between rottenness and death.

Through my works, I try to create affection toward this neglected but ubiquitous process of life. For example, in my site-specific installation Quing (2019) at Jupiter Artland, I highlighted how the rotting and decomposition of plant-based compost can in fact generate energy. This energy was then used to power an outdoor bioheater that, in turn, created the ideal conditions for fungi and other microorganisms to exist inside the gallery. I think that rottenness is shunned and marginalized by society because it is connected to the collective experience and passage of time, which contrasts with consumerism. One of the most apparent consequences of capitalism is that it constantly devours and discards. As consumers, we are also prime discarders. For example, in the bathroom or when we are taking out the trash, we push a button or close a lid and “undesired” products are gone, out of our sight. This ease of disposal extends to our interpersonal relationships. On social media, with the click of a button, we can unfollow or block someone, we can limit our interactions with and access to a person or information, etc. In my practice, I think critically about these forms of human-centrism and individualism that exist on many different scales.

I think this is the opposite of how things work when environments are not abused. Things don’t simply vanish or end. Just like the law of physics dictates: nothing is lost; nothing is created; everything is transformed. That is one of the main problems with the consumerist society in which we live. There is a lack of sustainability and responsibility for cycles of production, which has led to our current ecological crises. How can I deal with the fact that my body is transforming and aging when popular and visual culture informs me that this natural state of my organic matter is wrong? We are constantly bombarded with images from the makeup industry, from the cult of perfectly fit bodies, and dealing with the intense neurosis of appearance motivated by the fashion industry, plastic surgery, and anti-agism. Our collective desire to constantly consume “new” products and lifestyles has contaminated the possibility of existing as organic beings bound by time-based transformations. As I understand it, ecological apathy is rooted in the contradiction that we can care for the environment while simultaneously being careless consumers. Taking rottenness out of the margins is one solution to breaking out of this apathetic state that signals an uncaring denial of ecological issues. I offer a counterproposal that we create an acquaintanceship, friendship, and kinship with rottenness. If I live long enough with rotten matter, I wonder if I can make peace with myself and understand that my body is also undergoing organic changes. This cohabitation has made a significant impact on my life and made me more aware of the existence of other beings. It has motivated me to keep in contact with them, to learn more about them, and to continue to learn from them about how to be on this planet.

MMT: You have previously articulated the isolation from Brazilian culture you experienced growing up and, alternatively, the strong, embodied pull you feel toward your Indonesian roots. Have you found points of contact between your experience and those of other groups in Brazil that share similar feelings of isolation or disidentification? How have these connections left an impact on your practice?

DL: Acknowledging my own pain and trauma was how I initially found commonalities between my personal experiences and those of other groups in Brazil and beyond. My experience has been specific, due to the cultural isolation from my Indonesian diaspora while growing up in Brazil. I deal with the lingering feeling of isolation by extending my attention and practice to diverse communities, and trying to identify and find comfort with each group. I do this while understanding that there will always be fundamental differences between narratives. Maybe the common feelings of isolation or disidentification stem from an experience of brokenness, which can be repaired by the creation of new bonds.

As a person of Asian descent, or a Pessoa Amarela in Brazilian Portuguese (literally, “Yellow Person”), I have looked for guidance from and am grateful to the communities that have developed necessary strategies for survival under what has long been normalized oppression (for example, those communities subjected to Brazil’s 338-year history of slavery and the genocide of its indigenous people). Their knowledge has been an important source of learning, and I honor them through my practice.

Narrative reparation is one key frame of action in my practice. How can I socially and ecologically contribute to this action in my work? I try to do this by devoting time to create images and propositions that make “marginal” issues or groups that I identify with (like rottenness) more approachable.

WBH: You received degrees in fine art and teaching fine art. How does this pedagogical foundation influence your artwork/practice?

DL: Three key concepts in my artistic practice have been shaped by my teaching studies at São Paulo State University (UNESP): the pedagogy of autonomy (a concept from Paulo Freire2Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998). First published 1996 in Brazil.), analyzing the world through visual culture and not only through fine arts, and unlearning as a tool of living. This education gave me an understanding of art as a useful expression of deep social critique and contribution. I like to challenge myself by asking how my artwork can contribute to my life and to the communities that I surround myself with.

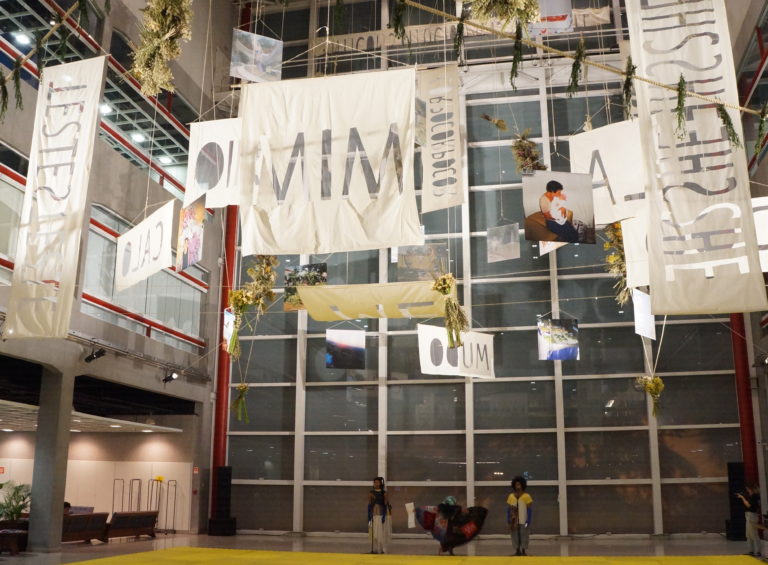

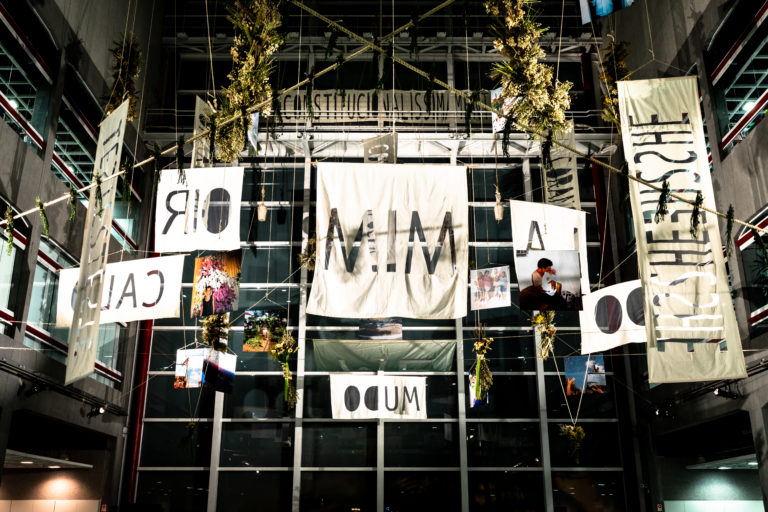

I often make works that are homages to the people and other-than-humans with whom I have developed strong kinship. This artistic process has allowed me to learn and connect more deeply with the world around me. For instance, the installation and performance work Lindinalva and the Balm (2016) was a testament to the ninety-five years of my late grandmother’s life. The site-specific installation Death Center for the Living Presents: East to East (2018), co-conceived with Anerina da Costa (my aunt), and artists Carmen Garcia and JUP do Bairro, was a multilingual installation that included archival images, poems, and performative elements that functioned as a lab of collective practice and authorship. Fortunately, through my work, I was also able to honour my father, who recently died of Covid-19 at age sixty-four. I titled my debut gallery exhibition Lie Liong Khing (2015) after him. These acts have given me peace, as they bear witness to the passage of time and become a testimony to life.

- 1“Quing” is a neologistic combination of the words “queen” and “king,” alluding to a nonbinary and non-deterministic take on gender.

- 2Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998). First published 1996 in Brazil.