If landlessness is another condition that transforms Africans into wanderers, with nothing but their labor to sell for a pittance, then the genre of landscape painting in South Africa represents a space-time of possession and dispossession. Implicit in Gladys Mgudlandlu’s landscapes is a reminder of how the ownership of land has historically epitomized South African nationhood. Mgudlandlu’s wayward ways with the semantics of landscape painting demonstrate the necessity of breaking away from formalities in order to create a space for reclamation and recovery.

Gladys Mgudlandlu’s Xhosa name, given to her at birth was Nomfanekiso, which in English, extraordinarily, means a picture of a person. Her name suggests that her path into the world of image-making was preordained through Xhosa naming practices. Gladys Mgudlandlu (1917–1979) was born in rural Peddie, South Africa.1Peddie is a region in the Eastern Cape province. During the apartheid era, it was a part of the Ciskei Bantustan homelands located outside the South African apartheid nation state. The Ciskei, like all other Bantustans, was a “tribal” reserve in which Xhosa-speaking Black people were confined. The Bantustan system, designed according to a “divide and rule” policy, separated Africans according to their “tribal” ethnicity. Furthermore, Bantustans served to strip away Black citizenship in white South Africa, where Africans had to carry passports as migrant laborers. According to Mahmood Mamdani, when the Natives Land Act was passed in 1913, 87 percent of South African land was designated for whites and the remaining 13 percent broken up into tribal Bantustan homelands for the African population. Mahmood Mamdani, “Settler Colonialism: Then and Now,” Critical Inquiry 41, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 608 Her mother died at an early age, and she was subsequently raised by her maternal grandmother. Like other Black artists of her generation, Gladys Mgudlandlu is considered a self-taught artist, a designation that fails to acknowledge the ancestral and indigenous knowledge passed down to her by way of her grandmother. Through her forebear, Mgudlandlu was initiated into the tradition of Mfengu and Xhosa mural painting. By instilling knowledge of the regional landscape, her grandmother also shared ways of creating that would not typically have been offered in a Western-style art curriculum—such as the use of local stones, which could be sharpened to make pencils. She exposed Mgudlandlu to the different regions of the Eastern Cape, which at the time was called Ciskei, where she could source natural clays in a variety of raw hues, and she taught her how to carve yellowwood (uMcheya, a tree native to South Africa) into everyday objects, such as needles for knitting and crocheting. In 1961, a year after the bloodshed of the Sharpeville massacre in 1960,2The PAC (Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania), a breakaway faction of the ANC (African National Congress) launched an anti-pass campaign against the pass laws requiring Africans to carry passports in white South Africa. On March 21, 1960, the PAC called on its supporters to leave their passes at home and gather at their nearest police station to make themselves available for arrest. The PAC believed that if thousands of people were arrested, then the jails would be filled and the economy would come to a standstill. When the marchers reached Sharpeville’s police station, the policemen lined up there subsequently opened fire, killing sixty-nine people. The pass laws were lifted temporarily and then reinstated on April 6, 1960. Rory Bester and Okwui Enwezor, Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of EverydayLife (New York: International Center of Photography, 2013), 172. Gladys Mgudlandlu staged her first solo exhibition in South Africa. There is little doubt that racial tensions were running high as the exhibition benevolently took place in the offices of the Liberal Party in Cape Town. For a white South African audience evading culpability, Mgudlandlu’s rural Peddie landscapes could be subsumed into an apolitical and palatable form of artistic expression. In 1963, the South African writer Bessie Head, would become one of Gladys Mgudlandlu’s prominent interlocuters. In her review “Gladys Mgudlandlu: The Exuberant Innocent”, Head identified a mood of escapism surrounding the consumption of the artist’s work, stating, “Who wants to be reminded of the terrors of township living? It is ugly, horrible and sordid.”3Bessie Head, “Gladys Mgudlandlu: The Exuberant Innocent,” New African 2, no. 10 (November 1963): 208–9. Unbeknownst to some of her critics including Bessie Head, Gladys Mgudlandlu did in fact paint township imagery, perhaps not as frequently as her natural landscapes, but she did indeed undertake township scenes, which I will discuss in this essay. Although her natural landscapes could be dismissed as escapist, this is partially because of the commonly held assumption that the landscape genre is a safe, apolitical subject. But the question of land cuts deep into the inner core of all modern settler-colonial formations because it illuminates the ongoing condition of native and indigenous peoples’ dispossession.

Painting landscapes for those “displaced in place,” inhabiting a “house arrest kind of existence”

Described as an expressionist, Gladys Mgudlandlu evaded modernist classifications of her practice. In her own words, she preferred to be called a “dreamer imaginist.”4Elza Miles, Namfanekiso Who Paints at Night: The Art of Glady Mgudlandlu (Vlaeberg: Fernwood Press, 2002), 10. The loaded act of creating her own terms was a reach toward a new idiom, one outside of the modernist framework. This experimentation with agency evinces the way that she saw herself as operating beyond South Africa’s Eurocentric conventions of modernist painting. Gladys Mgudlandlu’s kinship to birds is echoed in her technical use of a bird’s-eye view, a perspective that often configures the pictorial space of her work. Moreover, her aerial views are likened to motion, which Bessie Head associated with escapism. In her review Head accuses Mgudlandlu of performing “a kindly service” for those who may prefer to forget and turn their backs to the ongoing terrors of township life. While paying attention to Head’s trenchant observation, there remains a way in which to think about Mgudlandlu’s “escapism” politically. Could it be that Mgudlandlu was heeding the call to those who have been “displaced in place,” to those who are “relegated to a homeland that is not home at home.”5Fred Moten, preface to The Black Register, by Sithole Tendayi (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020), 10.

Gladys Mgudlandlu’s escapist brush strokes perhaps respond to the nervous tension that comes with inhabiting a “home-arrest kind of existence” that is incisively described by Thabo Jijana in Rented Grave: Looking Beyond The Rural-Urban Dichotomy.6Thabo Jijana, “Rented Grave: Looking Beyond The Rural-Urban Dichotomy,” Chimurenga Chronic, 2017, https://chimurengachronic.co.za/the-rented-grave-looking-beyond-the-rural-urban-dichotomy/ Significantly, even her critic Bessie Head left South Africa in 1964.7Craig Mackenzie, Bessie Head: An Introduction (Makhanda: National English Literary Museum, 1989), 5. As a matter of fact, Head arrived in Botswana as a stateless refugee having to report to the police on a weekly basis.

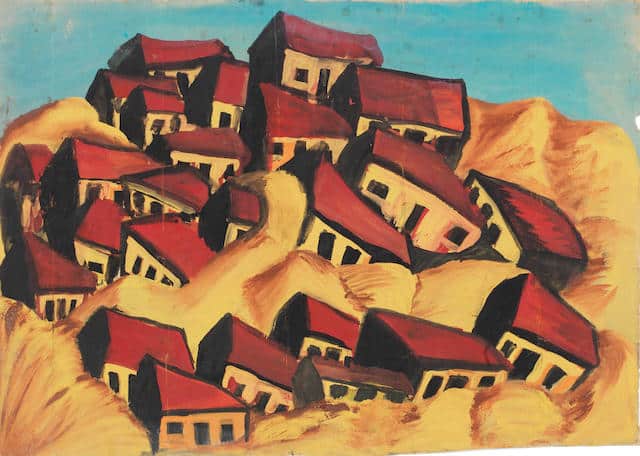

This condition of being “displaced in place” is visually encoded in her township scenes, which barely display a semblance of human presence. Take, for instance, her eerie depictions of the empty four-room matchbox houses in the township of Gugulethu, where she lived as an adult. In Gugulethu (1963; fig. 1), Mgudlandlu’s houses slant and slope with kinetic energy, as if they are reeling in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Some of them are on the verge of toppling, precariously half buried in the ground, with the sand dunes rising up to the windows. Packed closely together as they disappear into the earth, they appear to be caught in quicksand, which is swallowing them whole. The void of human presence contrasts sharply with the crowded township scenes by Mgudlandlu’s contemporary George Pemba (1912–2001). A fine example of Pemba’s township scenes, his painting New Brighton jostles and overflows with Black social life.

If landlessness is another condition that transforms Africans into wretched wanderers with nothing but their labor to sell for a pittance, then the genre of landscape painting represents a space-time of possession and dispossession. Implicit in Gladys Mgudlandlu’s landscapes is the reminder that the ownership of land has historically epitomized South African citizenship. Contextually, land ownership is not only apparent in the lines of the South African national anthem,8“Out the blue of our heaven, out the depths of our sea, over our eternal mountain ranges, where the cliffs give answer.” This line from “die Stem” was originally sung in Afrikaans. Here, it has been translated into English. This section is a part of the old apartheid national anthem that was later joined into the new, post-apartheid national anthem “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica.” In isiXhosa, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica” translates as “God Bless Africa.” In public commentary, it is often said that the post-apartheid South African national anthem animates the famous observation by the late Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta, “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened our eyes, they had the land and we had the Bible.” Muzi Mthembu ksMabika, “The Role Played By Christianity In Land Dispossession”, News 24, 2017, https://www.news24.com/news24/mynews24/the-role-played-by-christianity-in-land-dispossession-20170414 it is also emblazoned within the genre of landscape painting itself. Such is the case of the Afrikaner nationalist painter Jakob Hendrik Pierneef (1886–1957), who declared that “art has to walk with the nation and grow with it.”9Juliette Leeb-du Toit, “Land and Landlessness: Revisiting the South African Landscape,” in Visual Century: South African Art in Context,vol. 1, 1907–1948, ed. Jillian Carmen (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2011), 183. Pierneef’s views on landscape painting flourished alongside the influence of Hendrick Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid. In the effort to bolster and naturalize white appropriation of indigenous land, Verwoerd strategically reclassified Black African “Natives” as “Bantus,” affirming the idea that white people were now also natives of Africa.10Brian Lapping, Apartheid: A History (London: Grafton, 1986), 180. Pierneef is known for paintings such as An Extensive View of the Farmlands (1926), in which the South African landscape is rendered in a flattening, rigid geometric style devoid of emotion. More notably, his paintings of indigenous land are emptied of Black Africans, reproducing in visual terms, a Verwoedian political order. Within a settler-colonial context, landscape painting performs the dual labor of deterritorializing Africans while perpetuating a deadening form of visuality. This is a self-serving, imperial-masculinist fantasy that imagines Africa as an empty, virgin interior ready to be broken, owned, and put to work. Moreover, in this instance, it becomes crucial to discern and distinguish Mgudlandlu’s insistence on painting the land within the context of a genre that operated to nullify her ancestral and indigenous connections to it. Mgudlandlu’s energetic brushstrokes do not flow from an imperialist fantasy of dominion over nature.

By contrast, for her, the land resonates as a site of restorative ancestral refuge away from the immediate terrors of urbanized enclosures. However, there is a nostalgic ring to this, because rural Peddie was a part of the Ciskei was, in fact, a Bantustan homeland reserve. The Apartheid Bantustan reserves were modeled on the American reservation system,11In the same essay, Mamdani further connects South Africa’s settler-colonial technology to that of North America, which he calls the first settler modern state in modern times. He writes: “The pass system first originated in the slave plantations of the American South which were designed to regulate the movement of slaves outside the plantation.” Mahmood Mamdani, “Settler Colonialism: Then and Now,” Critical Inquiry 41, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 609. which had been established in North America more than fifty years before. In the words of Mahmood Mamdani, “The American ‘reservation’ became the South African ‘reserve.’”12Ibid, 608. As we start to contextualize Mgudlandlu’s rural landscapes of Peddie within the broader apparatus of a global settler colonial technology called ‘the reserve’, her work begins to signify ambivalently. From this perspective, the rural Bantustan is a simulation of refuge and a space devoid of national presence.13In Antiblackness, Frank Wilderson argues that Bantustans were spaces absent of national presence. Frank Wilderson, “Walking,” in Antiblackness, ed. Moon-Kie Jung and João H. Costa Vargas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 47.

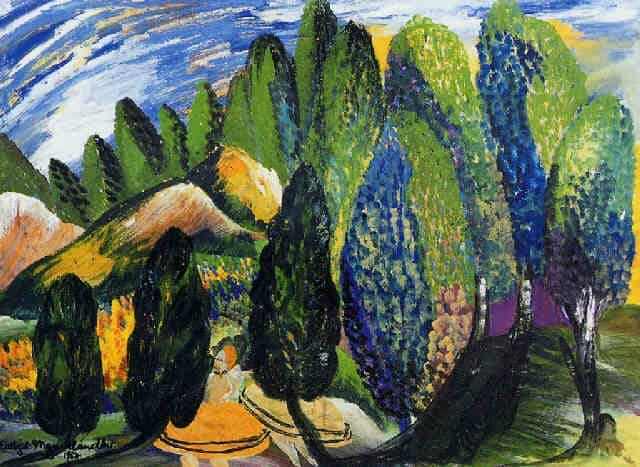

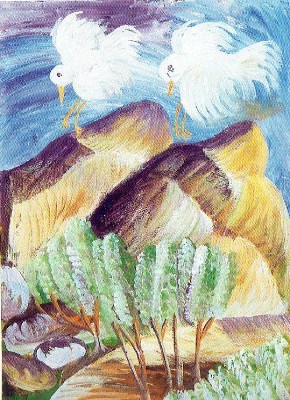

In Two Girls Running Through a Forest (1962; fig. 2), for instance, Mgudlandlu blended her figures into a natural treescape, her quick pointillist brushstrokes resonate with a desire to blend into the wilderness and break free. Within the image, on either side of the two girls running, there are three dark trees with unusually curved trunks uncannily leaning toward each other. She bends them to shield the two figures blending in and disappearing from sight. Painted in the opaque medium of gouache, Honey Birds (1961; fig. 3) marks a breakthrough in Mgudlandlu’s career, while denoting her first taste of critical success. Displayed in 1961 at her first exhibition, Honey Birds is painted in meandering elegant lines and harmonious warm and golden sunlit tones. The painting is likely to have been inspired by scenic views of the Amathole, which is close to where Mgudlandlu grew up. The mountain range forming the northern boundary of the district has an escarpment with slopes covered in lush forests of yellowwood, Cape chestnuts, and other indigenous trees. Red clays and yellow soils dominate the region. In Honey Birds, Mgudlandlu vividly depicts a mother bird who, perched atop a high mountainous landscape, tends to her hatchlings. Mother and Chicks (1961), drawn with lines of deep blues and greens, is a similarly tender scene of a black mother bird nesting and nurturing her young upon a dense grassy patch.

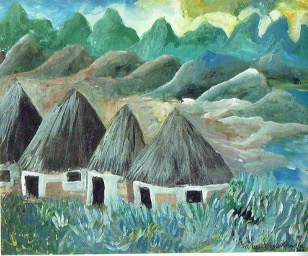

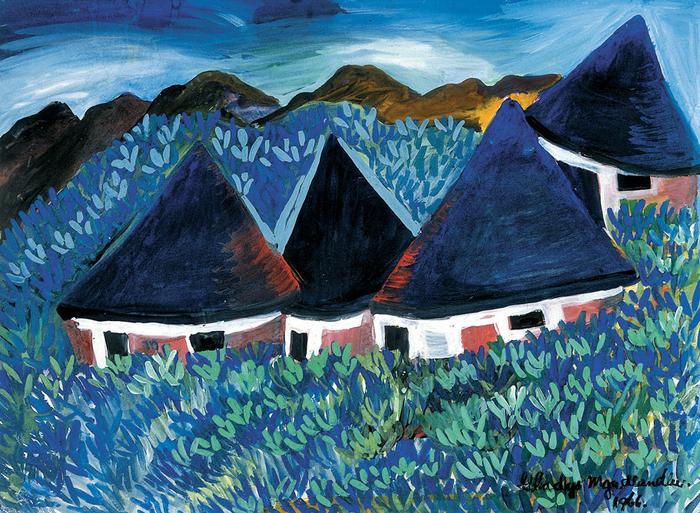

Mgudlandlu’s evocation of the maternal immediately points to her role as a single mother to her children, Malvern and Linda, and it perhaps can also be read as a homage to her grandmother, who died in 1957. More implicitly, it points to the way she primarily made a living through gendered professions such as nursing and teaching—occupations historically associated with care and women’s work. Gladys loved teaching and taught in several primary schools in Gugulethu. According to Elza Miles (born 1938), Mgudlandlu was known to have gone out of her way to nurture her pupils’ talents. Her landscapes of Peddie are an extension of this maternal cord of significance. In Xhosa Homestead (1966; fig. 4) and Huts (1966; fig. 5), Mgudlandlu draws mountains and hills in rounded shapes and lines that suggest “the nurturing aspects of the earth, resembling women’s breasts.”14Elza Miles, Land and Lives: A Story of Early Black Artists (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1997), 46.

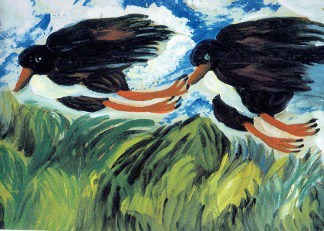

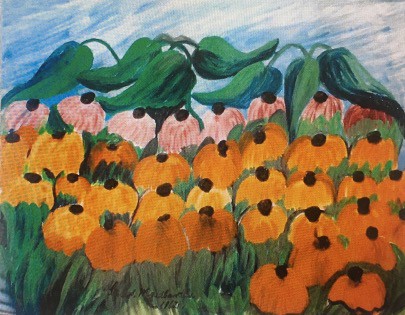

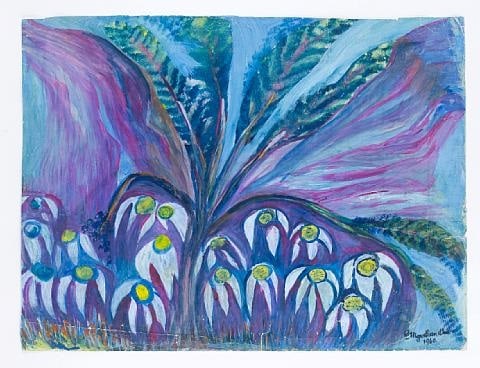

When they are not nestled on the ground, evoking maternal refuge, her birds fly above dotted trees and rustic highlands, such as in Two white birds flying over mountains and trees (1962; fig. 6). Their feet hang in a hovering motion, as though they are about to land. Mgudlandlu paints her feathered friends with an endearing charm, endowing them with an uncanny familiarity. This renders an impression of a human presence passing in animal form. Such is the case of the black Oystercatchers (1964; fig. 7), who glide across the page, meeting our gaze, eye to eye, their legs curved backward into the sky like lanky human arms. This quality of blending the human into the animal and into nature is a loaded artistic gesture that is not exclusive to this painting, as it can also be detected in Flowers (1962; fig. 8). Here, Mgudlandlu directs our gaze to the ground, to a grassroots level. What at first glance looks like a lively congregation of black figures clad in stripy pink and orange gowns dwelling under leafy sheaths or huddled together, turns out to be a bunch of daisies. Their petals droop downward, recurved so that their black stigmas resemble Black heads. Enveloped by the leaves above them as if to protect them from the elements, the flowers appear to pulsate side by side, evoking the warm charisma of a choral movement. Away from the realities of apartheid urban life, this composition is a remarkable yet ambivalent statement that evokes visual metaphors of marronage and Black cohabitation with nature, even in the rural, a space of “the reserve.” Once more, this aesthetic is depicted in an earlier composition of Flowers (1960; fig. 9). In this painting, the long stalks extend from the body of the plant, suggesting the limbs of a protective maternal figure. The stalks cocoon the human-shaped flowers below them in a manner that belies immediate recognition.

In all these paintings, Mgudlandlu’s brushwork is consistent. Evading precision, or the lingering over minor details, the haste of her brushwork endows her images with a moving, restless energy. Her choice of subject matter sheds light on her inner world and her upbringing in rural Peddie. Her reverence for the wilderness is effused with maternal metaphors, which evoke the fervor of a burgeoning African ecofeminist aesthetic.

Mgudlandlu’s work enjoyed a remarkably positive reception, and it was a commercial success in her lifetime. Her second exhibition, in 1962 at Rodin Gallery, was described as “the most enthusiastic exhibition ever held in Cape Town.”15This was Gladys Mgudlandlu’s second exhibition, but it was her first exhibition at the Rodin Gallery, where 58 out of 76 of her paintings were sold. The mass interest and unbridled excitement towards her work on the night of her opening was palpable “Only a hundred people were invited and 500 turned up…women in evening dress and their escorts jammed the stairway of the Rodin Gallery to view and buy the works of African school teacher Gladys Mgudlandlu.” Elza Miles, Namfanekiso Who Paints at Night: The Art of Glady Mgudlandlu (Vlaeberg: Fernwood Press, 2002), 27. Despite her success, both sides of the apartheid divide were not short on criticism. From the white media, by way of newspapers such as the Cape Argus, Die Burger,and the Evening Post,criticism was primarily directed at her lack of formal training. Neville Dubow, former professor at the University of Cape Town, commented that her figure compositions are “unconvincing” and “lacking in development.”16Ibid., 27. By contrast, Black critics, such as Bessie Head and George T. Kulati, who in their own ways were reckoning with the political turbulence of the time, focused their acerbic criticism on her preference for painting natural landscapes, which to them signified an apolitical stance. Mgudlandlu created for herself a unique place in South African art history. She experimented with bending and breaking the conventions of the settler-colonial landscape genre, evoking an unsettling fugitive moment. She achieved this by rendering the natural environment in ways that recall indigenously African conceptions of the wilderness as animated places with intrinsic presence—not as an absent space awaiting settler-colonial occupation and development.

Despite the criticism of Mgudlandlu’s being an escapist, her real life was far from it. She suffered her fair share of the tragedy and poverty that typified Black life in her time. In 1969, an earthquake destroyed her work, and at some point, her shack burned down, taking all of her possessions with it.17Ibid.,20. In 1971, she was hit by a car. She never fully recovered from her injuries and died penniless. There is a cold and gray monochrome photograph of Gladys Mgudlandlu’s friend Sheila Sontange standing at Gugulethu cemetery. Sontange is bending over, pointing at the unkempt grassy patch where Gladys Mgudlandlu was buried in 1979. Aside from the caption, there is no visible tombstone; indeed, nothing in the picture signifies that this is Gladys Mgudlandlu’s final resting place. From the viewer’s point of view, there could be anybody or nobody buried under the overgrown spot to which Sontange directs our gaze. Once again, as Mgudlandu’s paintings make salient, in this photograph taken after her death, the subject of the wilderness continues to reassert its enveloping presence. Moreover, as the demand for land restitution continues to seethe under the gloss of South Africa’s “rainbowist”18Rainbow nationalism is a nation-building founding myth of South Africa’s post-apartheid democracy. It is based on the state-endorsed belief that after South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, the country entered into some kind of a unified post-racial future defined by equality. politics, Mgudlandlu’s “wayward”19This is a term introduced by Saidiya Hartman in her book Wayward Lives. In the book she uses the term “waywardness” alongside “fugitive” in order to denote the practices of Black women who refused to be governed by the strictures of racial enclosures and respectability. Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), xv. ways with the colonial landscape genre show us the necessity of breaking away from formalities in order to create a space for reclamation and recovery.

In reproducing the images contained in this text, the Museum obtained the permission of the rights holders, whenever possible. If the Museum could not locate the rights holders, notwithstanding good-faith efforts, it requests that any contact information concerning such rights holders be forwarded so that they may be contacted for future editions.

- 1Peddie is a region in the Eastern Cape province. During the apartheid era, it was a part of the Ciskei Bantustan homelands located outside the South African apartheid nation state. The Ciskei, like all other Bantustans, was a “tribal” reserve in which Xhosa-speaking Black people were confined. The Bantustan system, designed according to a “divide and rule” policy, separated Africans according to their “tribal” ethnicity. Furthermore, Bantustans served to strip away Black citizenship in white South Africa, where Africans had to carry passports as migrant laborers. According to Mahmood Mamdani, when the Natives Land Act was passed in 1913, 87 percent of South African land was designated for whites and the remaining 13 percent broken up into tribal Bantustan homelands for the African population. Mahmood Mamdani, “Settler Colonialism: Then and Now,” Critical Inquiry 41, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 608

- 2The PAC (Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania), a breakaway faction of the ANC (African National Congress) launched an anti-pass campaign against the pass laws requiring Africans to carry passports in white South Africa. On March 21, 1960, the PAC called on its supporters to leave their passes at home and gather at their nearest police station to make themselves available for arrest. The PAC believed that if thousands of people were arrested, then the jails would be filled and the economy would come to a standstill. When the marchers reached Sharpeville’s police station, the policemen lined up there subsequently opened fire, killing sixty-nine people. The pass laws were lifted temporarily and then reinstated on April 6, 1960. Rory Bester and Okwui Enwezor, Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of EverydayLife (New York: International Center of Photography, 2013), 172.

- 3Bessie Head, “Gladys Mgudlandlu: The Exuberant Innocent,” New African 2, no. 10 (November 1963): 208–9.

- 4Elza Miles, Namfanekiso Who Paints at Night: The Art of Glady Mgudlandlu (Vlaeberg: Fernwood Press, 2002), 10.

- 5Fred Moten, preface to The Black Register, by Sithole Tendayi (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020), 10.

- 6Thabo Jijana, “Rented Grave: Looking Beyond The Rural-Urban Dichotomy,” Chimurenga Chronic, 2017, https://chimurengachronic.co.za/the-rented-grave-looking-beyond-the-rural-urban-dichotomy/

- 7Craig Mackenzie, Bessie Head: An Introduction (Makhanda: National English Literary Museum, 1989), 5.

- 8“Out the blue of our heaven, out the depths of our sea, over our eternal mountain ranges, where the cliffs give answer.” This line from “die Stem” was originally sung in Afrikaans. Here, it has been translated into English. This section is a part of the old apartheid national anthem that was later joined into the new, post-apartheid national anthem “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica.” In isiXhosa, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica” translates as “God Bless Africa.” In public commentary, it is often said that the post-apartheid South African national anthem animates the famous observation by the late Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta, “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened our eyes, they had the land and we had the Bible.” Muzi Mthembu ksMabika, “The Role Played By Christianity In Land Dispossession”, News 24, 2017, https://www.news24.com/news24/mynews24/the-role-played-by-christianity-in-land-dispossession-20170414

- 9Juliette Leeb-du Toit, “Land and Landlessness: Revisiting the South African Landscape,” in Visual Century: South African Art in Context,vol. 1, 1907–1948, ed. Jillian Carmen (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2011), 183.

- 10Brian Lapping, Apartheid: A History (London: Grafton, 1986), 180.

- 11In the same essay, Mamdani further connects South Africa’s settler-colonial technology to that of North America, which he calls the first settler modern state in modern times. He writes: “The pass system first originated in the slave plantations of the American South which were designed to regulate the movement of slaves outside the plantation.” Mahmood Mamdani, “Settler Colonialism: Then and Now,” Critical Inquiry 41, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 609.

- 12Ibid, 608.

- 13In Antiblackness, Frank Wilderson argues that Bantustans were spaces absent of national presence. Frank Wilderson, “Walking,” in Antiblackness, ed. Moon-Kie Jung and João H. Costa Vargas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 47.

- 14Elza Miles, Land and Lives: A Story of Early Black Artists (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1997), 46.

- 15This was Gladys Mgudlandlu’s second exhibition, but it was her first exhibition at the Rodin Gallery, where 58 out of 76 of her paintings were sold. The mass interest and unbridled excitement towards her work on the night of her opening was palpable “Only a hundred people were invited and 500 turned up…women in evening dress and their escorts jammed the stairway of the Rodin Gallery to view and buy the works of African school teacher Gladys Mgudlandlu.” Elza Miles, Namfanekiso Who Paints at Night: The Art of Glady Mgudlandlu (Vlaeberg: Fernwood Press, 2002), 27.

- 16Ibid., 27.

- 17Ibid.,20.

- 18Rainbow nationalism is a nation-building founding myth of South Africa’s post-apartheid democracy. It is based on the state-endorsed belief that after South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, the country entered into some kind of a unified post-racial future defined by equality.

- 19This is a term introduced by Saidiya Hartman in her book Wayward Lives. In the book she uses the term “waywardness” alongside “fugitive” in order to denote the practices of Black women who refused to be governed by the strictures of racial enclosures and respectability. Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), xv.