Through the lens of Bertina Lopes’s Tribute to Amílcar Cabral (1973), C-MAP Africa fellow Nancy Dantas suggests an intra- and transcontinental cartography of modernist transfers and invocations. Excavating, cross-referencing, and resettling scattered archival traces, the author uses this “lost” canvas as a springboard for a partial, located reading of Lopes’s anticolonial trajectory in view of her aesthetics of solidarity and long-distance nationalism.

On a good day, the work of an art historian and curator begins with a distinctive kind of quiet, slow, intense, haptic engagement that the medium of painting irrevocably invokes. One revels in the play of color, composition, and surface, which points, in a push and pull, to one’s locatedness as an outside observer. Such is the grip and enchantment of losing oneself in the powerful historical and pictorial folds of a gripping painting. The delirium of this love affair also calls for a certain amount of sobriety and analysis; turning the canvas around, looking for the clues, utterances, and telltale signs that whisper its life story—its time and location of making, title, travels, ownership, and perhaps, through a tear or droplet, some of its misfortunes.

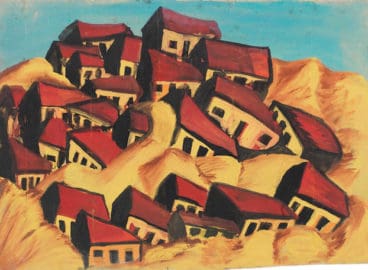

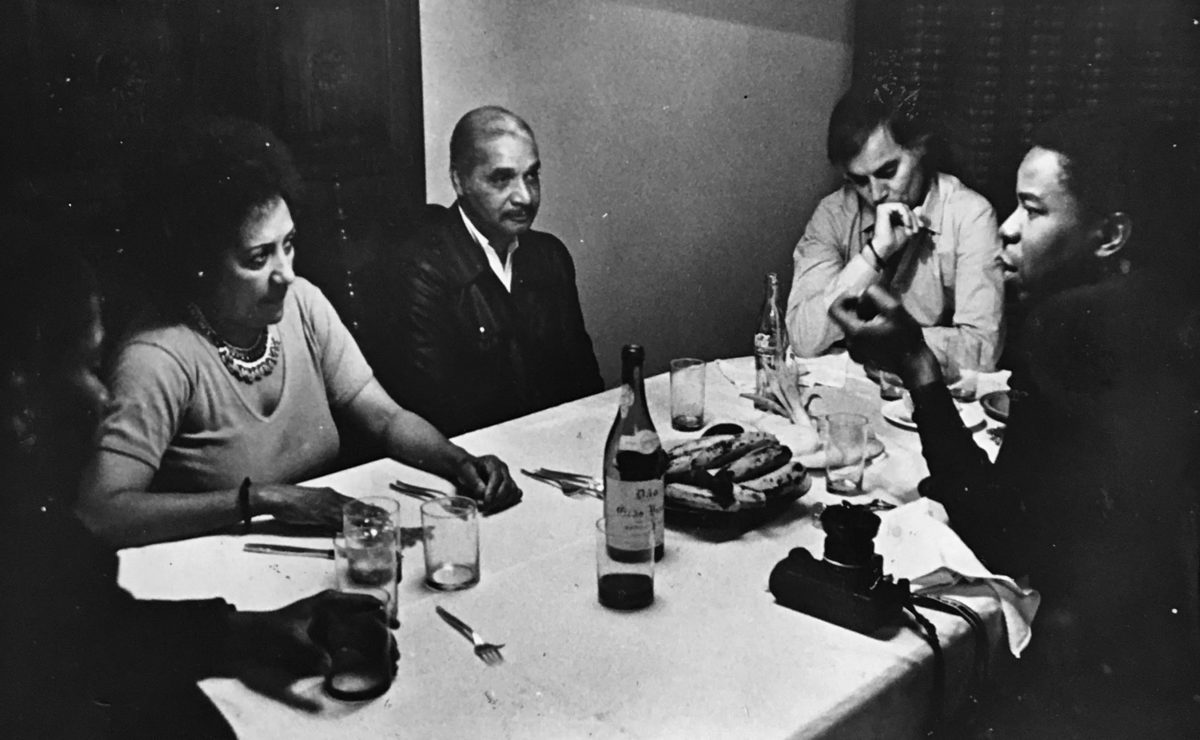

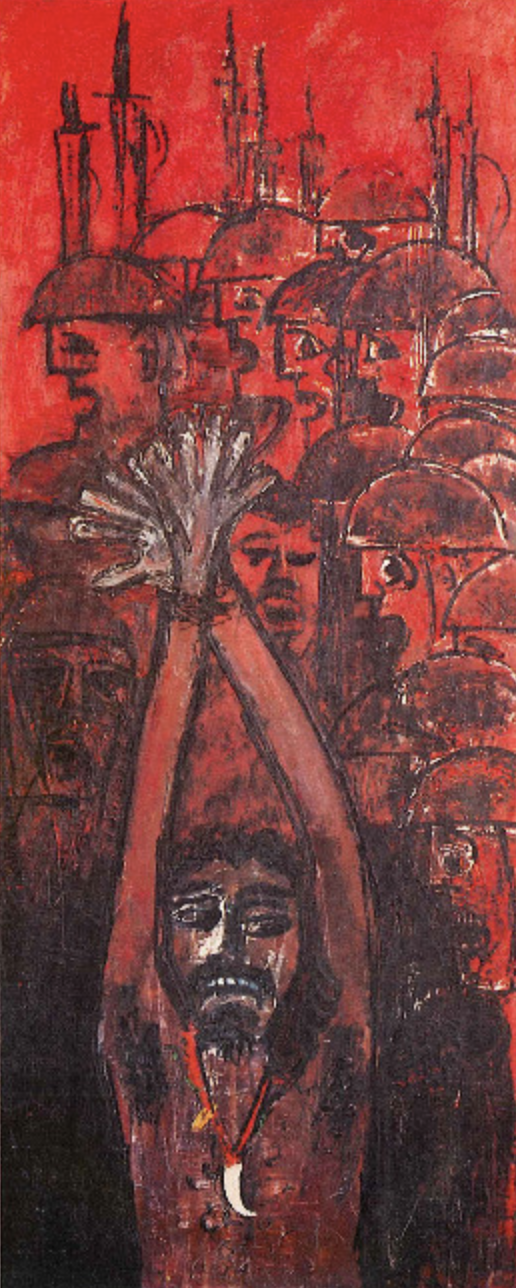

Executed by polyhedral and prolific Mozambican artist Bertina Lopes (1924–2012) in the watershed year of 1973,1I have borrowed the term “polyhedric” from Claudio Crescentini, who refers to Lopes as a “polyhedric artist, imbued in the political and social.” See Claudio Crescentini, Bertina Lopes: Arte e Antagonismo (Rome: Erreciemme, 2017), 17. For a short biography of the artist, see Mary Angela Schroth, “Bertina Lopes,” AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/bertina-lopes/; and Mary Angela Schroth and Francesca Capriccioli, “Bertina Lopes,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 3 (Fall/Winter 1995): 18–21. the verso of Omenagem a Amílcar Cabral (Tribute to Amílcar Cabral; fig. 2) discloses an emotional outcry on the death of revolutionary leader Amílcar Cabral. Just a few months after his meeting in October 1972 with African American organizations in New York City, Cabral was killed by a group of armed men—Portuguese agents who, in the early hours of the morning of January 20, 1973, took his life at point-blank range.2For introductory reading on the death of Cabral, see Eduardo de Sousa Ferreira, “Amílcar Cabral: Theory of Revolution and Background to His Assassination,” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 3, no. 3 (1973); and António Tomás, Amílcar Cabral: The Life of a Reluctant Nationalist (London: Hurst and Company, 2021).

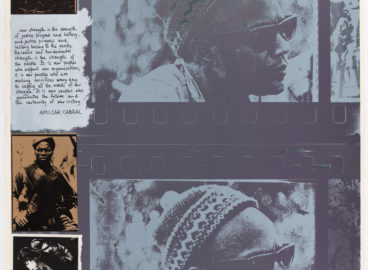

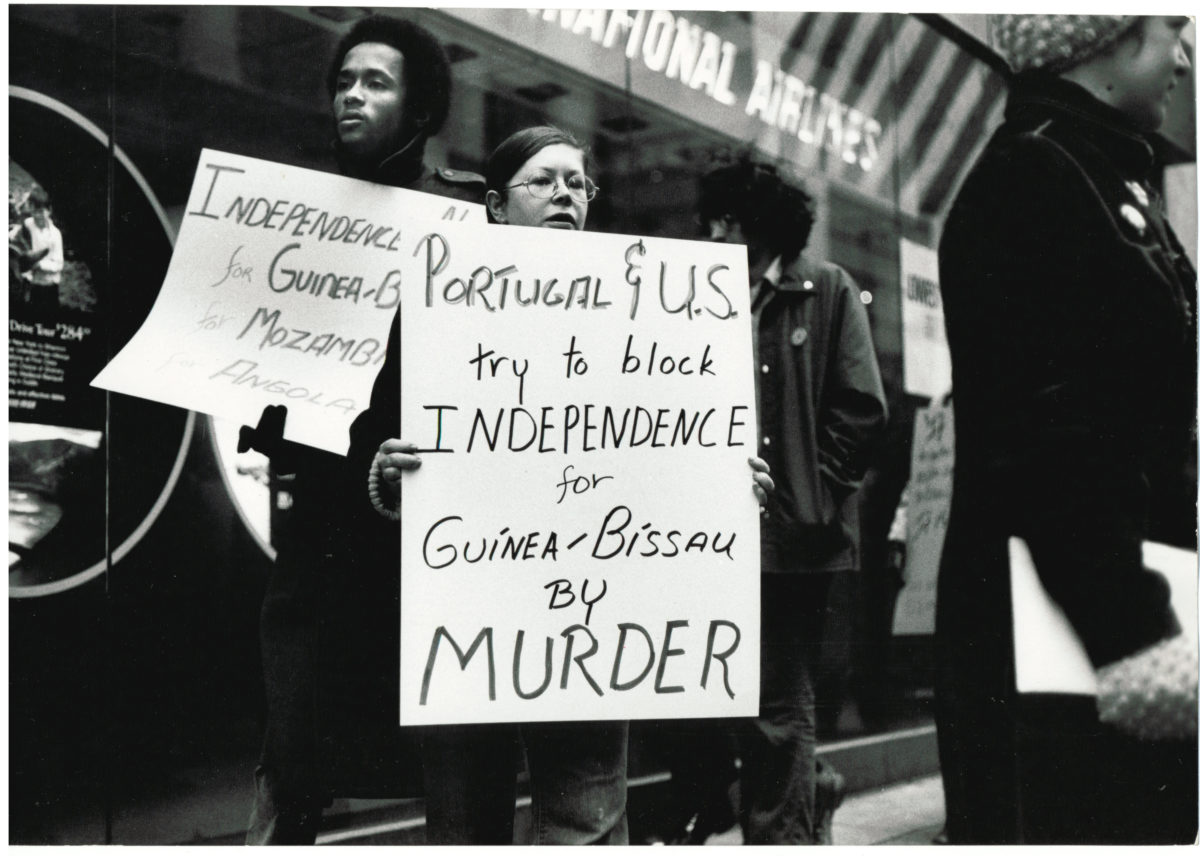

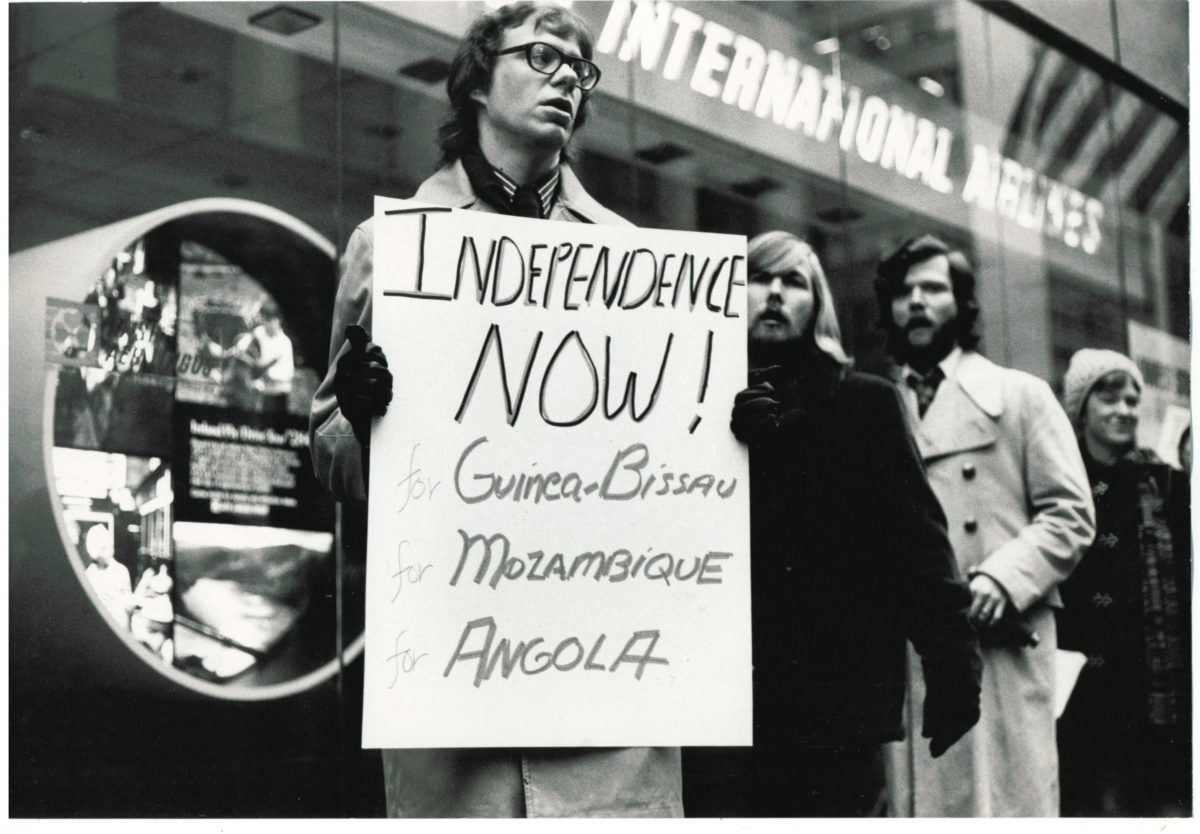

A founder of the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (African Independence Party for Guinea and Cape Verde, or PAIGC) in 1956, and one of only four university graduates from Guinea-Bissau, Cabral traveled across the country between 1952 and 1954 as a young agronomist, gaining profound knowledge of the land and its people, which he prioritized in his intertwined, decolonially-minded political and cultural practice. Under his leadership, the people of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde galvanized into one fighting force against Portuguese colonialism. Cabral was aware of the large number of plots to assassinate him,3In 1970, PIDE organized an operation called “Amílcar Cabral,” which aimed to liquidate the leader. A bounty of 1,000,000 escudos was placed on his head. See ibid., 188. but was firm in his belief that the anticolonial struggle would continue without him. As he stated in an interview in October 1971: “If I die tomorrow, nothing will change in the ineluctable evolution of the fight of my people and their victory. . . . We will have dozens, hundreds of Cabrals in our people. Our nation will find a militant to continue the work.”4Ibid., 187.

Expressed in the artist’s expansive and distinctive cursive handwriting, in an inimitable mélange of Portuguese and Italian (the two languages that Lopes made her own), one reads the following illuminating declaration: “Cabral has died physically, not only in Guinea, but in all of Africa, in all the world! But he lives on . . . forever!” Splayed across the wooden stretcher, Lopes also provided an explicit instruction to herself—as well as to her dealers, family, and stewards—that this work should not be sold. The different pens she used for her palimpsestic inscriptions along the wooden stretcher signal how she returned to this painting time and again, how meaningful it was to her—and how she wished to see it included in her historiography.5It is unclear how or why this painting was recently auctioned off in Lisbon, or why the artist’s explicit directive, expressed by way of a repeated note, was ignored. One senses that she knew that she, like Cabral, would receive a Judas kiss.

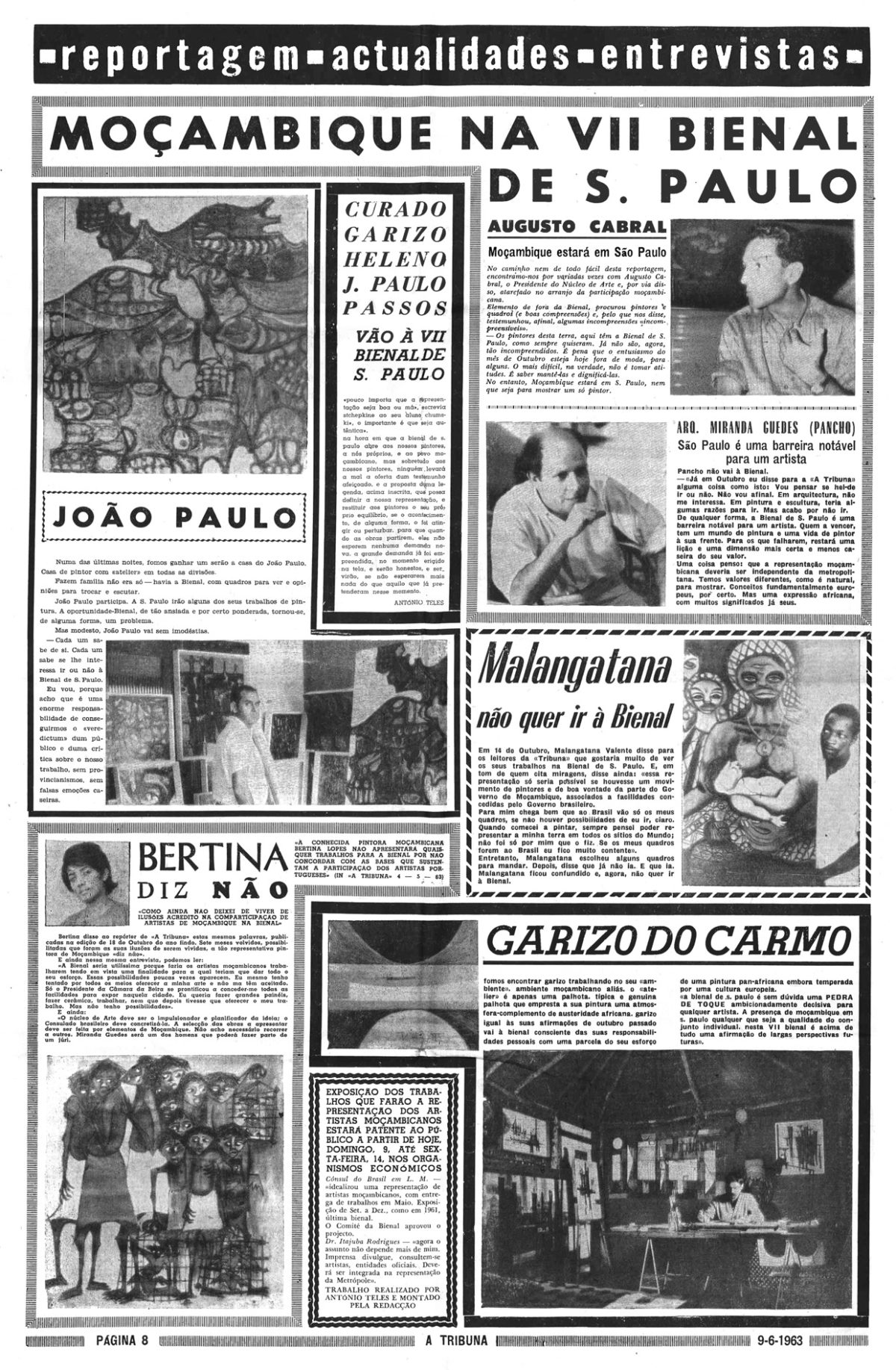

Lopes had been living as an exile in Europe for approximately nine years when she painted Tribute. She had fled Mozambique in 1964 to accept a bursary offered to her by Lisbon’s Gulbenkian Foundation.6The Gulbenkian Foundation had a vested interest in Mozambique at this time. According to African World, the foundation distributed a number of subsidies to sites in Lourenço Marques. This included 400 contos toward the construction of a center for the social work of Munhuana, 400 contos toward improvement and expansion of the Negro Associateship Centre, 400 contos toward the acquisition of the building occupied by the Nucleus of Art (which Lopes’s peers Malangatana Valente Ngwenya and Pancho Guedes frequented), 400 contos toward the construction of a new center for the Native Association of Mozambique, and 500 contos toward the enlargement of the Alvaro de Castro Museum. See “Social and Cultural Aid in Portugal’s Overseas Provinces: Gulbenkian Foundation Grants for Angola and Mozambique,” African World, October 1963. Consequently, the Foundation’s president Azeredo Perdigão and his deputy Sá Machado took a twenty-eight-day field trip to Mozambique in July 1964. Sá Machado would soon become one of Lopes’s patrons. Published in 1964, Luís Bernardo Honwana’s now-classic short story “Nós Matámos o Cão-Tinhoso!” (“We Killed Mangy-Dog”)—a trailblazer in anticolonial short stories from Southern Africa, which included fragments of drawings by Lopes and her actual handprint7For more on these works, see Nancy Dantas, “Bertina Lopes: A Militant with a Brush,” Revista de Comunicação e Linguagens 54 (2021): 215–34.—had just been banned, and the two found themselves in the crosshairs of the colonial police.8Honwana was arrested in 1964 on the charge of having brought subversive material into Mozambique from Swaziland. Prior to this, she was part of a group of artists who took an anticolonial stance, communicating their withdrawal from the 1963 Bienal de São Paulo, believing that she would be representing a Portuguese province, not Mozambique, in the “Ultramar”9After the constitutional reform of 1951, references to the Colonial Empire and its colonies were dropped from official texts and substituted by the term “ultramar” or “overseas provinces.” This term thus designated non-European territories under Portuguese sovereignty. (fig. 5).10I wish to acknowledge and thank Pedro d’Alpoim Guedes for drawing my attention to this illuminating material and for sharing with me the Tribuna clipping included here. The refusing artists included Malangatana Valente Ngwenya and Pancho Guedes, Pedro’s father, who were very cautious about what they said and “often couched their messages in ambiguity.” Guedes adds, “The Tribuna was a newspaper that tried hard to reach out to people on important issues, but every article had to go through two censorship wash cycles—one focused on political scrutiny—run by the security police (PIDE and later DGS) and the other connected with ‘moral’ issues presided over by the Catholic church.” Pedro d’Alpoim Guedes, email correspondence with author, March 13, 2021. Leaving behind the stability of a teaching post as well as her twin boys, Lopes left Mozambique in 1964 to study ceramics in Lisbon under Querubim Lapa (Portuguese, 1925–2016), until another opportunity emerged in Rome to study classical art.

Despite her work having been the object of two major exhibitions in Lisbon (in 1973 and 1979, respectively),11Both exhibitions were held at the Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon. The first was a display of the work she produced as a Gulbenkian fellow, exhibited for a short period between June 20 to 30, 1972. This show traveled from Lisbon to Porto. The second exhibition was her first and only Portuguese survey, held from April 27 to May 23, 1993 (like her fellowship exhibition, a selection of these works traveled at the end of the Lisbon viewing to Cape Verde). Lopes was never represented by a Portuguese (or, for that matter Italian) commercial gallery—a reality that begs further engagement and unpacking—bearing the brunt of building and maintaining a career as a Black, “third-world” visual artist and mother. Against the odds, she harnessed her innermost energies to produce a singular oeuvre that contributes to our understanding of the emergence of modernism in Mozambique as a nationalist aspiration. Arguably inspired by her first husband, poet Virgílio de Lemos (Mozambican, 1929–2013), Lopes significantly bent her European expressionist training to her African idiom, producing an initial body of works that exposed the depredations of Portuguese colonialism and fascism. Refusing social mores, aesthetic atomization, and capitalist tethers, she painted, sculpted, and contributed to the nationalist and pan-African cause and aesthetic, producing extraordinary abstract and geometric works in her later years, opening her home to the Mozambican cause, and giving her work away freely to the friends and causes she believed in most.

An instance of what Italian critic Claudio Crescentini has termed a “phenomenology of commitment,”12Crescentini, Bertina Lopes: Arte e Antagonismo, 18. according to her Italian widower and founder of the Bertina Lopes Archive in Rome,13Franco Confaloni, interview by Nancy Dantas (Rome, July 14, 2021). Tribute is likely to have been executed during a stay in Lisbon,14The painting may have been included in her 1973 exhibition at Galeria Alvarez, Porto. Jaime Isidoro, the founder of the gallery (and himself an artist), died on January 21, 2009. I have been unable locate the gallery’s archive or other records of this exhibition. possibly to visit one of her sisters, Custódia Lopes, who in 1973, formed part of the 10th legislature of the Estado Novo (under António de Oliveira Salazar) as a congresswoman for Mozambique. Despite existing on opposite ends of the political spectrum—Bertina, a cautious socialist and nationalist, and her sister, Custódia, an incongruous representative of the colonial government—the siblings maintained close contact, and Custódia, who traveled the world, always kept her artist sister in mind. As a matter of fact, while residing in Paris, Custódia would, in a gesture denoting some ambivalence toward the colonial regime, send postcards and reproductions of Picasso’s work to Bertina, then in Lourenço Marques. Bertina in turn used these images in her revolutionary lessons at the General Machado all-girls school.15It is important to bear in mind that Picasso’s work was prohibited in conservative, pro-Salazar Portuguese circles, which viewed it as subversive and “communist.” See Crescentini, Bertina Lopes: Arte e Antagonismo, 21.

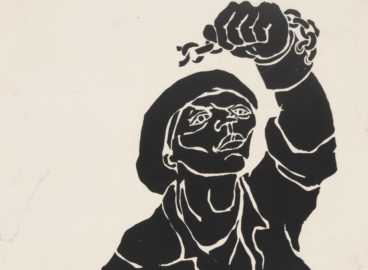

Measuring 55 1/8 by 74 13/16 inches (140 x 190 cm), Tribute is dominated by a thick, deep impastoed crimson background and a central messianic, totemic figure with outstretched arms that reach across the painting, embracing an abstracted, flattened Black crowd that peoples the lower half of the canvas.16This was not the first time Lopes brazenly represented a Black Christ. Her figurative Identificazione (Cristo) of 1965 predates Tribute. In the periphery, four executioners in pith helmets, spread out in menacing pairs on each side, are rendered in profile with glaring eyes and snarling mouths. These figures recall the Portuguese secret police, or PIDE, who not only surveilled the artist while she was living in Mozambique, having considered her a person of interest, but also, and of direct import to this work, recruited Cabral’s assassins from its Tarrafal prison. A haunting presence in her life, these men populate several of Lopes’s anticolonial works from the period. Such is the case of the multiple soldiers in Senza Titolo (Rappresaglia) (Untitled [Retaliation], 1963; fig. 6) or Cantiga do Batelão (Boat Song, 1963; fig. 7), which is dedicated to her friend, nationalist poet José Craveirinha (Mozambican, 1922–2003), who was arrested by the PIDE briefly in 1964 and for a longer period in 1968. Boat Song portrays the arrested poet, his arms raised in the air, surrounded by a group of helmets. Around the captive poet’s neck, Lopes painted a large luminous tooth tied to a bright red string, arguably a reference to Craveirinha’s poem on the dilemma of vengeance: “Olho por olho / Eu ou tu / Beijo por beijo / Unha por unha / Milho por milho / Nós ou eles / Eles ou nós / Dente por dente / bala por bala / E . . . poetas cem por cento no exterior deste dilemma / ou Pátria ou Nada!”(“An eye for an eye / Me or you / A kiss for a kiss / A nail for a nail / Mealie meal for mealie meal / us or them / Them or us / A tooth for a tooth / A bullet for a bullet / And . . . poets beyond this dilemma / Homeland or Nothing!”17Fragment from the poem “Olho por olho dente por dente,” reproduced in Fátima Mendonça, “Noémia de Sousa e José Craveirinha nos trilhos poéticos da Mafalala,” in Mafalala: Memórias e Espaços de um Lugar, eds. Margarida Calafate Ribeiro and Walter Rossa (Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2021). Translation by author. José Craveirinha is considered one of the most important poets writing in Portuguese in the last century. The poem to which Lopes’s title alludes, “Cantiga do Negro Batelão,” can be found in José Craveirinha, “Seven Poems by José Craveirinha,” trans. Stephen Gray and José Craveirinha, introduction by Stephen Gray, Portuguese Studies 12 (1996), 202. In her later Omaggio per la morte di Picasso (Homage on the Death of Picasso, 1974; fig. 8), three of these signature figures of repression appear on the left, on the heels of a group of supplicating women.18According to Crescentini, Lopes was clandestinely exposed to Picasso while studying in Lisbon, and was particularly drawn to a self-portrait from his blue period, possibly Self-Portrait (1906; Musée Picasso, Paris). Their ominous presence also features in a painting by her peer Malangatana Valente Ngwenya (Mozambican, 1936–2011) entitled Grito de Liberdade (The Cry for Freedom, 1973), which, accessioned into the collection of The Museum of Modern Art in 2020, is also dedicated to Cabral.19The inscription on the back indicates that it was made as a tribute to Eduardo Mondlane and Amílcar Cabral. In addition, information on the back indicates that the work was featured in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC), held in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1977. See Hendrik Folkerts, Felicia Mings, and Constantine Petridis, “Three Curators, Three Favorites,” Art Institute of Chicago website, posted October 1, 2020, https://www.artic.edu/articles/848/three-curators-three-favorites. Ngwenya, unlike Lopes, has portrayed the soldiers not only as observers, but also as infiltrates, translating social life in Mozambique at the time when no one could be trusted.

With Tribute, Lopes transmutes the body of Cabral. No longer a man, he is risen, a forebear who looks down on us from a vantage point above. Cabral is the purveyor of an essential, vital force that we witness in the radiating, thick lines that surround the central auratic figure. Arguably, Lopes drank from the negritudinist cup in her homage,20I refer to negritude here as a modernist strategy toward an emancipatory African revival, a turning of artists toward their roots, and the recircuiting of European media and techniques to create a new form of, in the case of Lopes and her peers, Mozambican art. imbibed via “Black Blood” by poet Noémia de Sousa (Mozambican, 1926–2002), who like Lopes, frequented the Associação Africana.21For a translation of Black Blood, see https://poetryinthemountains.com/2013/01/27/poetry-from-mozambique/. It should be noted that the collected works of Noémia de Sousa (née Carolina Noémia Abranches de Sousa) were published in 2016 under the same title. This anthology (in Portuguese) includes all of her poems, which were written between 1948 and 1951. See Noémia de Sousa, Sangue Negro (São Paulo: Editora Kapulana, 2016). Neither imitation nor representation, Lopes’s translation aimed to synthetically render Cabral as a syncretic ancestor, ultimately presentifying him as a messianic apparition. Masked, the totemic figure is a liminal performer, moving between spaces, between the community and its outskirts, the living and the dead. The threshold that is crossed and the fusion that is achieved allows for communion between the living onlookers and the deceased, between African and Christian iconography, bridging the chasm between the deceased and his people.

Like it was for her modernist, nationalist peers, poets José Craveirinha, Noémia de Sousa, and coconspirator Luís Bernardo Honwana (fig. 1), art for Lopes was part of identity formation, reconnecting the self to her antepassados, or those who came before us. In the battle between assimilation22A legal system that institutionalized the Portuguese view at the time of European superiority over African ways and customs. According to this racist and injurious system, assimilados were set apart from the indígena majority, who were subject to onerous taxes, a customary legal system, and conscription into a debt-bondage or forced-labor system known as chibalo. For more, see Lilly Havstad, “Multiracial Woman and the African Press in Post-World War II Lourenço Marques, Mozambique,” South African Historical Journal 68, no. 3 (September 2016): 398. and re-africanization,23In short, this is a return to root traditions. This re-africanizing gaze, as Mantia Diawara notes, posits religion where anthropologists (read colonial Europeans) see idolatry, history where they see primitivism, and humanism where they see savagery. See Manthia Diawara, African Cinema: Politics & Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992). it would be Africa that would rise and take primacy—a resurrection embodied and communicated by Lopes in Tribute for coming generations.

- 1I have borrowed the term “polyhedric” from Claudio Crescentini, who refers to Lopes as a “polyhedric artist, imbued in the political and social.” See Claudio Crescentini, Bertina Lopes: Arte e Antagonismo (Rome: Erreciemme, 2017), 17. For a short biography of the artist, see Mary Angela Schroth, “Bertina Lopes,” AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/bertina-lopes/; and Mary Angela Schroth and Francesca Capriccioli, “Bertina Lopes,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 3 (Fall/Winter 1995): 18–21.

- 2For introductory reading on the death of Cabral, see Eduardo de Sousa Ferreira, “Amílcar Cabral: Theory of Revolution and Background to His Assassination,” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 3, no. 3 (1973); and António Tomás, Amílcar Cabral: The Life of a Reluctant Nationalist (London: Hurst and Company, 2021).

- 3In 1970, PIDE organized an operation called “Amílcar Cabral,” which aimed to liquidate the leader. A bounty of 1,000,000 escudos was placed on his head. See ibid., 188.

- 4Ibid., 187.

- 5It is unclear how or why this painting was recently auctioned off in Lisbon, or why the artist’s explicit directive, expressed by way of a repeated note, was ignored. One senses that she knew that she, like Cabral, would receive a Judas kiss.

- 6The Gulbenkian Foundation had a vested interest in Mozambique at this time. According to African World, the foundation distributed a number of subsidies to sites in Lourenço Marques. This included 400 contos toward the construction of a center for the social work of Munhuana, 400 contos toward improvement and expansion of the Negro Associateship Centre, 400 contos toward the acquisition of the building occupied by the Nucleus of Art (which Lopes’s peers Malangatana Valente Ngwenya and Pancho Guedes frequented), 400 contos toward the construction of a new center for the Native Association of Mozambique, and 500 contos toward the enlargement of the Alvaro de Castro Museum. See “Social and Cultural Aid in Portugal’s Overseas Provinces: Gulbenkian Foundation Grants for Angola and Mozambique,” African World, October 1963. Consequently, the Foundation’s president Azeredo Perdigão and his deputy Sá Machado took a twenty-eight-day field trip to Mozambique in July 1964. Sá Machado would soon become one of Lopes’s patrons.

- 7For more on these works, see Nancy Dantas, “Bertina Lopes: A Militant with a Brush,” Revista de Comunicação e Linguagens 54 (2021): 215–34.

- 8Honwana was arrested in 1964 on the charge of having brought subversive material into Mozambique from Swaziland.

- 9After the constitutional reform of 1951, references to the Colonial Empire and its colonies were dropped from official texts and substituted by the term “ultramar” or “overseas provinces.” This term thus designated non-European territories under Portuguese sovereignty.

- 10I wish to acknowledge and thank Pedro d’Alpoim Guedes for drawing my attention to this illuminating material and for sharing with me the Tribuna clipping included here. The refusing artists included Malangatana Valente Ngwenya and Pancho Guedes, Pedro’s father, who were very cautious about what they said and “often couched their messages in ambiguity.” Guedes adds, “The Tribuna was a newspaper that tried hard to reach out to people on important issues, but every article had to go through two censorship wash cycles—one focused on political scrutiny—run by the security police (PIDE and later DGS) and the other connected with ‘moral’ issues presided over by the Catholic church.” Pedro d’Alpoim Guedes, email correspondence with author, March 13, 2021.

- 11Both exhibitions were held at the Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon. The first was a display of the work she produced as a Gulbenkian fellow, exhibited for a short period between June 20 to 30, 1972. This show traveled from Lisbon to Porto. The second exhibition was her first and only Portuguese survey, held from April 27 to May 23, 1993 (like her fellowship exhibition, a selection of these works traveled at the end of the Lisbon viewing to Cape Verde).

- 12Crescentini, Bertina Lopes: Arte e Antagonismo, 18.

- 13Franco Confaloni, interview by Nancy Dantas (Rome, July 14, 2021).

- 14The painting may have been included in her 1973 exhibition at Galeria Alvarez, Porto. Jaime Isidoro, the founder of the gallery (and himself an artist), died on January 21, 2009. I have been unable locate the gallery’s archive or other records of this exhibition.

- 15It is important to bear in mind that Picasso’s work was prohibited in conservative, pro-Salazar Portuguese circles, which viewed it as subversive and “communist.” See Crescentini, Bertina Lopes: Arte e Antagonismo, 21.

- 16This was not the first time Lopes brazenly represented a Black Christ. Her figurative Identificazione (Cristo) of 1965 predates Tribute.

- 17Fragment from the poem “Olho por olho dente por dente,” reproduced in Fátima Mendonça, “Noémia de Sousa e José Craveirinha nos trilhos poéticos da Mafalala,” in Mafalala: Memórias e Espaços de um Lugar, eds. Margarida Calafate Ribeiro and Walter Rossa (Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2021). Translation by author. José Craveirinha is considered one of the most important poets writing in Portuguese in the last century. The poem to which Lopes’s title alludes, “Cantiga do Negro Batelão,” can be found in José Craveirinha, “Seven Poems by José Craveirinha,” trans. Stephen Gray and José Craveirinha, introduction by Stephen Gray, Portuguese Studies 12 (1996), 202.

- 18According to Crescentini, Lopes was clandestinely exposed to Picasso while studying in Lisbon, and was particularly drawn to a self-portrait from his blue period, possibly Self-Portrait (1906; Musée Picasso, Paris).

- 19The inscription on the back indicates that it was made as a tribute to Eduardo Mondlane and Amílcar Cabral. In addition, information on the back indicates that the work was featured in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC), held in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1977. See Hendrik Folkerts, Felicia Mings, and Constantine Petridis, “Three Curators, Three Favorites,” Art Institute of Chicago website, posted October 1, 2020, https://www.artic.edu/articles/848/three-curators-three-favorites.

- 20I refer to negritude here as a modernist strategy toward an emancipatory African revival, a turning of artists toward their roots, and the recircuiting of European media and techniques to create a new form of, in the case of Lopes and her peers, Mozambican art.

- 21For a translation of Black Blood, see https://poetryinthemountains.com/2013/01/27/poetry-from-mozambique/. It should be noted that the collected works of Noémia de Sousa (née Carolina Noémia Abranches de Sousa) were published in 2016 under the same title. This anthology (in Portuguese) includes all of her poems, which were written between 1948 and 1951. See Noémia de Sousa, Sangue Negro (São Paulo: Editora Kapulana, 2016).

- 22A legal system that institutionalized the Portuguese view at the time of European superiority over African ways and customs. According to this racist and injurious system, assimilados were set apart from the indígena majority, who were subject to onerous taxes, a customary legal system, and conscription into a debt-bondage or forced-labor system known as chibalo. For more, see Lilly Havstad, “Multiracial Woman and the African Press in Post-World War II Lourenço Marques, Mozambique,” South African Historical Journal 68, no. 3 (September 2016): 398.

- 23In short, this is a return to root traditions. This re-africanizing gaze, as Mantia Diawara notes, posits religion where anthropologists (read colonial Europeans) see idolatry, history where they see primitivism, and humanism where they see savagery. See Manthia Diawara, African Cinema: Politics & Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).