How do you historicize the events of the dehistoricized? From its inception in 1948, the apartheid regime implemented a system of institutionalized racial segregation against the nonwhite citizens of South Africa. In recent years, a counter narrative has emerged of a group of artists and activists who viewed “culture as a weapon of struggle” against the oppressive policies of the apartheid regime. In this essay, curator Clive Kellner discusses the significance of the poster You Have Struck a Rock (1981) by Judy Seidman and Medu Art Ensemble in MoMA’s collection.

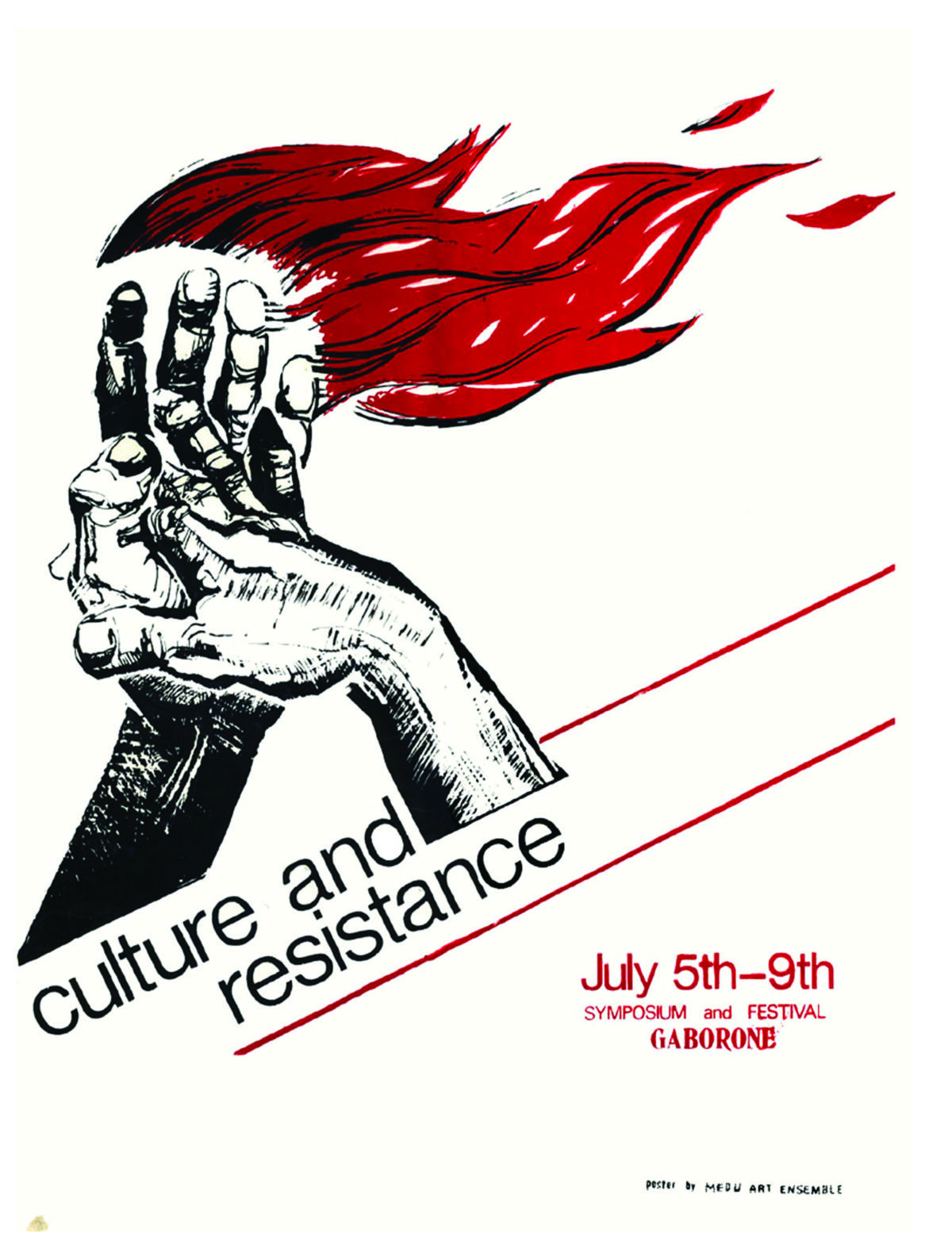

Medu Art Ensemble, a collective formed in 1978 in Gaborone, Botswana (in Sesotho, “medu” means “roots”), was “comprised of more than 60 visual artists, performers and writers, mainly South African exiles but with members from Botswana, Canada, Cuba, Sweden and North America.”1Sindi-Leigh McBride, “Long Read: The anti-apartheid posters of Medu,” New Frame, April 9, 2021, https://www.newframe.com/long-read-the-anti-apartheid-posters-of-medu/. One of Medu’s notable legacies was organizing the Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival of the Artsheld at the University of Botswana in Gaborone in 1982. More than nine hundred people from Europe, the United States, and Southern Africa attended.2The symposium was attended by artists, activists, and cultural workers from South Africa and in exile. Speakers and panelists included Nadine Gordimer, Mongane Wally Serote, Lindiwe Mabuza, Keorapetse “Bra Willie” Kgositsile, Dikobe Ben Martins, David Koloane, and Gavin Jantjes. See Kellner and Gonzalez, Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective, 162. The purpose of the symposium was to chart a way forward for the role of arts and culture in a new and free democratic South Africa. Medu was active from 1979 until June 14, 1985, when the South African Defence Force (SADF) launched a cross-border raid on African National Congress (ANC) targets in Gaborone, including several Medu members. Medu disbanded after the raid.

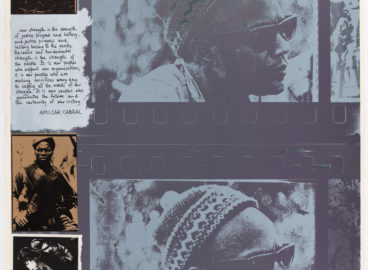

The collective consisted of six units: Publications and Research, Graphic Arts and Design, Music, Theatre, Photography, and Film. Apart from its focus on promoting resistance to apartheid in South Africa, Medu was active in training Botswana nationals and exiles as well as conducting workshops in various art disciplines and hosting live music and theatre events. Its “members adopted the appellation ‘cultural workers,’ choosing not to identify as artists because of the shared belief that as culture was of the people, it could not and should not be confined to the exclusionary art world of the apartheid era.”3McBride, “Long Read.” This idea is best expressed by Thami Mnyele (1948–1985), a Medu member and visual artist: “For me as craftsman, the act of creating art should complement he act of creating shelter for my family or liberating the country for my people. This is culture.”4Judy Seidman, “The Art of National Liberty: The Thami Mnyele and Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective,” in Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective, eds. Clive Kellner and Sergio-Albio Gonzalez, exh. cat. (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2008), 87. Medu drew inspiration from a variety of creative ideas and role models, including West Indian social philosopher Frantz Fanon and African writers such as Wole Soyinka and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, but also from more broadly categorized revolutionary thought and artists such as Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes, German playwright Bertolt Brecht, and Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, José Orozco, and David Siqueiros, and painter Frida Kahlo.5Medu members were inspired by a variety of influences, styles, and aesthetics, personally and collectively. In this regard, Medu aimed to strike a balance between African-generated cultural expression and other modes of artistic and revolutionary expression. For example, Berthold Brecht was known in the South African Black Consciousness movement of the 1970s; Keorapetse Kgositsile admired the Harlem Renaissance poets; and the Mexican muralists and painters influenced the Mozambican mural movement and were celebrated in international left-wing cultural events and festivals that Mongane Wally Serote, Keorapetse Kgositsile, and Mandla Langa attended through the African National Congress.

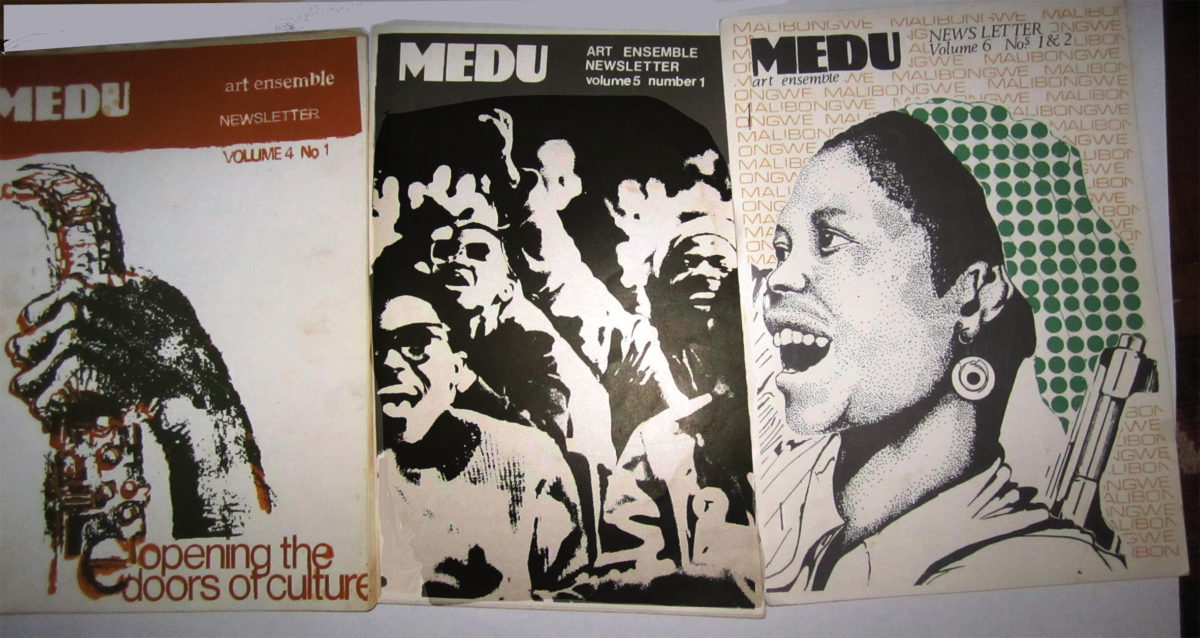

Key members of the Graphic Arts and Design unit during different periods were Sergio-Albio González (Cuban, born 1931; active in Medu 1979–85), Phillip Segola (South African, born 1948), Miles Pelo (South African, date of birth unknown; active in Medu 1979–83), Judy Seidman (American, born 1951; active in Medu 1981–85), Thami Mnyele (South African, 1948–1985; active in Medu 1979–85), Heinz Klug (South African, born 1957; active in Medu 1979–85), Gordon Metz (South African, born 1955; active in Medu 1979–85), Lentswe Eric Mokgatle (South African, date of birth unknown; active in Medu 1982–85), Petra Röhr-Rouendaal (German, date of birth unknown; dates active in Medu unknown), Basil Jones (South African, date of birth unknown; active in Medu 1979–81), and Adrian Köhler (South African, born 1951; active in Medu 1978–80).6The list of members of the Graphic Arts and Design unit is taken from Kellner and Gonzalez, Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective, 201. The unit designed and produced posters, covers, and illustrations for Medu’s newsletters and pamphlets. Decisions on artwork designs were made collectively and at times themes were commissioned by a general meeting of Medu members.7Decisions on artworks produced by the Graphic Arts and Design unit were made collectively, either ‘commissioned’ by a general meeting of Medu members, or proposed by other units or as by individual members. Judy Seidman, email message to author, August 25, 2021. Members of the unit established a set of guiding principles for the production of artwork designs, including that the message of the art stem from the community and not be a result of individual artistic genius, that each formal and aesthetic component of the work contribute to the message, and that the art should elicit a response from the audience based upon their own history and experience.8Ibid, 89. Medu’s posters have become icons of the liberation movement and more recently acknowledged for their aesthetic contribution within a larger canon of artistic creation.9Medu’s role in the liberation struggle and the artistic contribution of its graphic posters, in particular, have increasingly received acknowledgment, most recently in the exhibition The People Shall Govern! Medu Art Ensemble and the Anti-Apartheid Poster at the Art Institute of Chicago (2020) and previously in the Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective exhibition held at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (2008). Between 1979 and 1985, the unit produced approximately ninety posters that were smuggled into South Africa.

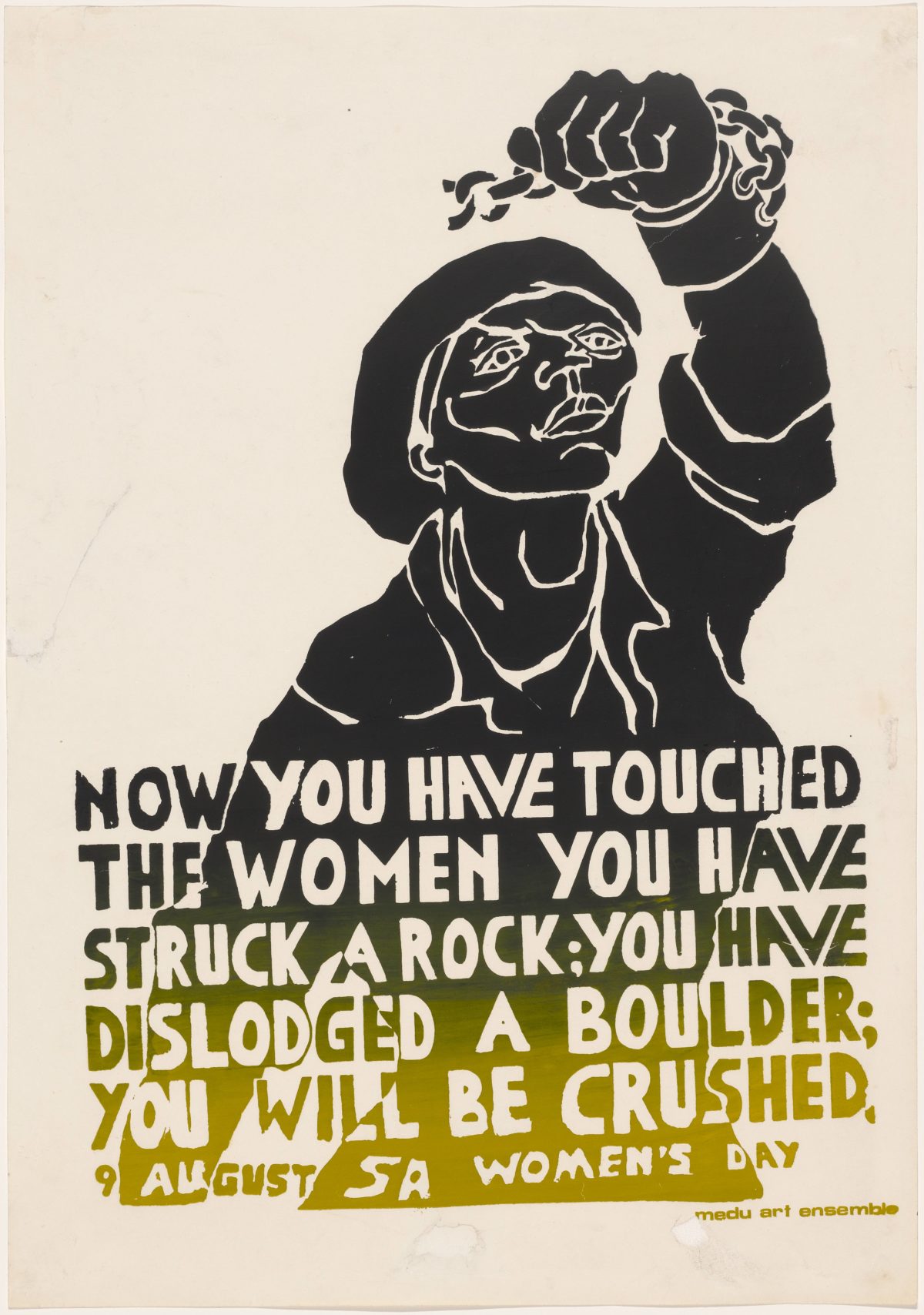

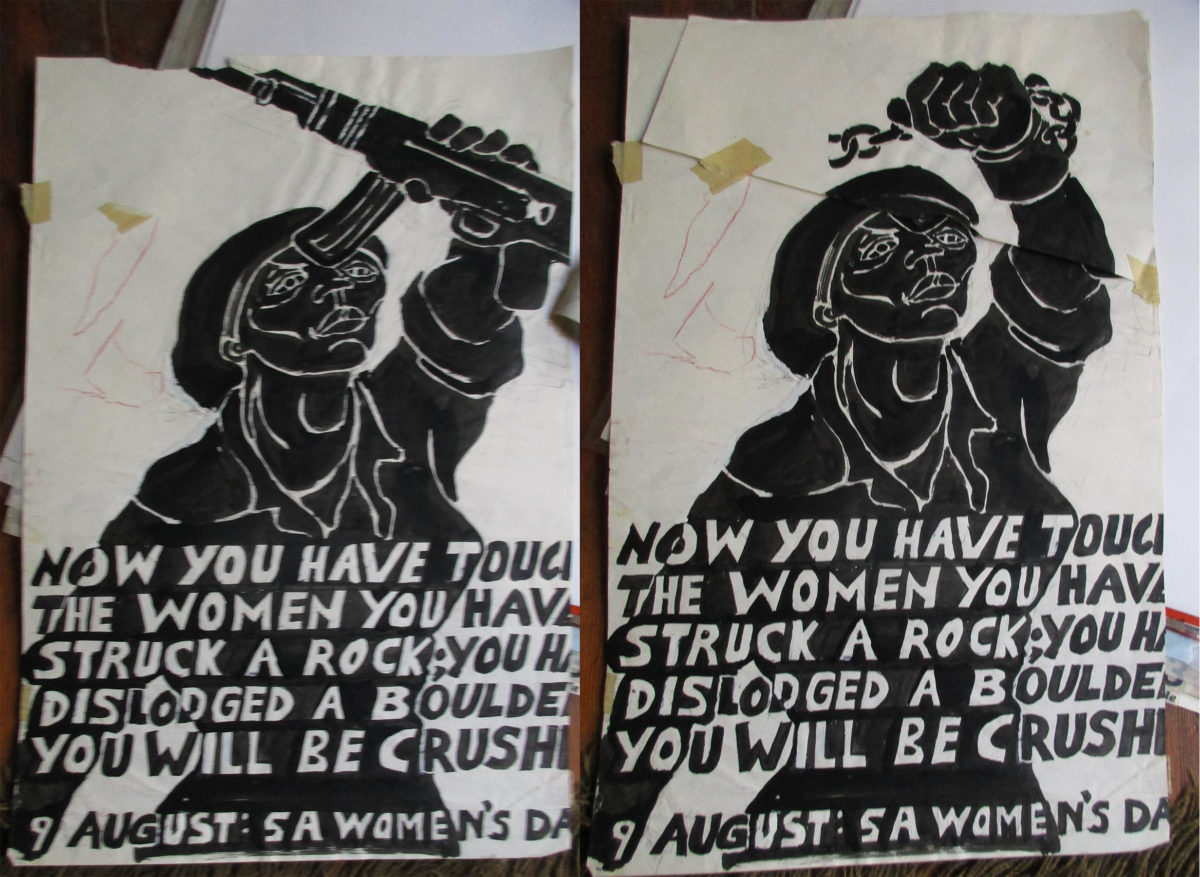

The graphic poster You Have Struck a Rock (1981), in MoMA’s collection, was produced to commemorate the Women’s Anti-Pass March of August 9, 1956 (now commemorated annually on August 9 in post-apartheid South Africa as Women’s Day). The march was organized by the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) and led by Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph, Albertina Sisulu, and Sophia Williams-De Bruyn.10For more on the march, see “9 August 1956: The Women’s Anti-Pass March,” Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/9-august-1956-the-women-s-anti-pass-march-africa-media-online/3QKisZ_nLurALA?hl=en. The apartheid government had proposed amendments to the “pass” laws that would further restrict the movement of Black women and require them to carry a document that regulated their movement and hours of transit. Twenty thousand women of all races marched to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to submit a petition in protest. J. G. Strijdom, then prime minister, refused to accept their petition. The women responded with the song “Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo” (“You strike the women, you strike a rock”), which has come to symbolize the courage and strength of South African women. According to the ANC, the emancipation of women must be an integral part of national liberation. In response, at a monthly Medu meeting, it was decided that a poster be produced to commemorate the women’s march.

As a member of the Graphic Arts and Design unit, Judy Seidman, an American-born artist and activist who moved to Gaborone in 1980, proposed an ink drawing of a woman holding an AK-47 and the full text “You have touched a woman, you have struck a rock; you have dislodged a boulder, you will be crushed.” It was decided to replace the AK-47 with a clenched fist and a broken chain. This change was made due to concerns that Medu needed to be cautious about portraying support for the armed struggle and thereby creating problems for the Botswana authorities, who had to be diplomatic with regard to its neighbor South Africa and apartheid. The resulting poster, You Have Struck a Rock (1981), was produced as a silkscreen using a cut-knife stencil and a single pull process to generate approximately 200 copies.11Judy Seidman, email message to author, July 8, 2021. You Have Struck a Rock (1981) has become an iconic symbol for women’s liberation and, in particular, the conviction and courage of Black women.

You Have Struck a Rock (1981) portrays an African image of solidarity against oppression that evokes a poster created in 1942 by J. Howard Miller (American, 1918–2004) titled We Can Do It! but later associated with Rosie the Riveter, an American feminist icon. Used as part of a campaign to recruit woman workers during World War II, the American poster became a symbol for women’s independence and equal rights. In a similar way, You Have Struck a Rock (1981) can be understood to function as a metonym for women’s rights and liberation against oppression. While stylistically the two images differ, with We Can Do It! embodying what would come to be seen as a Pop aesthetic, while You Have Struck a Rock (1981) reveals a cut-and-paste montage aesthetic, both posters pivot off the notion of an individual woman at the center of historical events and, therefore, shaping the course of history. In this way, there is a productive tension between the propaganda message of the poster medium linked to a collective social idea and the notion of the individual artistic identity behind the image. This tension is apparent in Medu as a collective formed around the idea of solidarity, utilizing the arts to stand against oppression, and yet comprised of individual artists and activists who have left an indelible mark on history.

- 1Sindi-Leigh McBride, “Long Read: The anti-apartheid posters of Medu,” New Frame, April 9, 2021, https://www.newframe.com/long-read-the-anti-apartheid-posters-of-medu/.

- 2The symposium was attended by artists, activists, and cultural workers from South Africa and in exile. Speakers and panelists included Nadine Gordimer, Mongane Wally Serote, Lindiwe Mabuza, Keorapetse “Bra Willie” Kgositsile, Dikobe Ben Martins, David Koloane, and Gavin Jantjes. See Kellner and Gonzalez, Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective, 162.

- 3McBride, “Long Read.”

- 4Judy Seidman, “The Art of National Liberty: The Thami Mnyele and Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective,” in Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective, eds. Clive Kellner and Sergio-Albio Gonzalez, exh. cat. (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2008), 87.

- 5Medu members were inspired by a variety of influences, styles, and aesthetics, personally and collectively. In this regard, Medu aimed to strike a balance between African-generated cultural expression and other modes of artistic and revolutionary expression. For example, Berthold Brecht was known in the South African Black Consciousness movement of the 1970s; Keorapetse Kgositsile admired the Harlem Renaissance poets; and the Mexican muralists and painters influenced the Mozambican mural movement and were celebrated in international left-wing cultural events and festivals that Mongane Wally Serote, Keorapetse Kgositsile, and Mandla Langa attended through the African National Congress.

- 6The list of members of the Graphic Arts and Design unit is taken from Kellner and Gonzalez, Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective, 201.

- 7Decisions on artworks produced by the Graphic Arts and Design unit were made collectively, either ‘commissioned’ by a general meeting of Medu members, or proposed by other units or as by individual members. Judy Seidman, email message to author, August 25, 2021.

- 8Ibid, 89.

- 9Medu’s role in the liberation struggle and the artistic contribution of its graphic posters, in particular, have increasingly received acknowledgment, most recently in the exhibition The People Shall Govern! Medu Art Ensemble and the Anti-Apartheid Poster at the Art Institute of Chicago (2020) and previously in the Thami Mnyele + Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective exhibition held at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (2008).

- 10For more on the march, see “9 August 1956: The Women’s Anti-Pass March,” Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/9-august-1956-the-women-s-anti-pass-march-africa-media-online/3QKisZ_nLurALA?hl=en.

- 11Judy Seidman, email message to author, July 8, 2021.