In July 1982, exiled artist Gavin Jantjes (born 1948) spoke before an audience of fellow South African cultural workers—politically committed artists, musicians, poets, and photographers—at the groundbreaking Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival in Gaborone, Botswana.1The Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival was held in Gaborone, Botswana, from July 5 to July 9, 1982. It was organized by members of the Medu Art Ensemble, a collective of exiled South African artists, poets, and writers based in Botswana, in affiliation with the African National Congress. The gathering’s significance is due, in part, to its assembling of cultural workers based in South Africa as well as living in exile across the world. Organized by Medu Art Ensemble, this event sought to clarify art’s relationship to the anti-apartheid movement.2For more on the Medu Art Ensemble, see Clive Kellner, “Culture as a Weapon of Struggle: The Art of the Medu Poster You Have Struck a Rock (1981),” post: notes on art in a global context, September 15, 2021, https://post.moma.org/culture-as-a-weapon-of-struggle-the-art-of-the-medu-poster-you-have-struck-a-rock-1981/. For his part, Jantjes proclaimed that if artists were to have a role in the struggle, “let it be to function as verbs in the grammar of culture.”3Gavin Jantjes, “The role of the visual artist,” July 1982 (exact date unknown), Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival, Gaborone, Botswana; transcribed in Gavin Jantjes, “The role of the visual artist,” Artrage: Inter-Cultural Arts Magazine no. 2 (February 1983): 2–3. As cultural stakeholders, he argued, artists could and must lend their talents to fuel collective resistance globally and, in particular, in South Africa. Crucially, they could help to preserve the collective histories that were threatened by erasure under white nationalist rule. In support of his stance, Jantjes enlisted the words of Guinean revolutionary Amílcar Lopes Cabral, founder of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), who stated in a speech given in London ten years prior, “I don’t need to remind you that the problem of liberation is also one of culture. In the beginning it’s culture, and in the end, it’s also culture.”4Ibid., 2. The quote is not attributed therein, but rather in Amílcar Cabral, “Speech made at a mass meeting in Central Hall, London, on 26th October 1971,” in Our People Are Our Mountains: Amílcar Cabral on the Guinean Revolution (London: Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola & Guiné, 1972), 8.

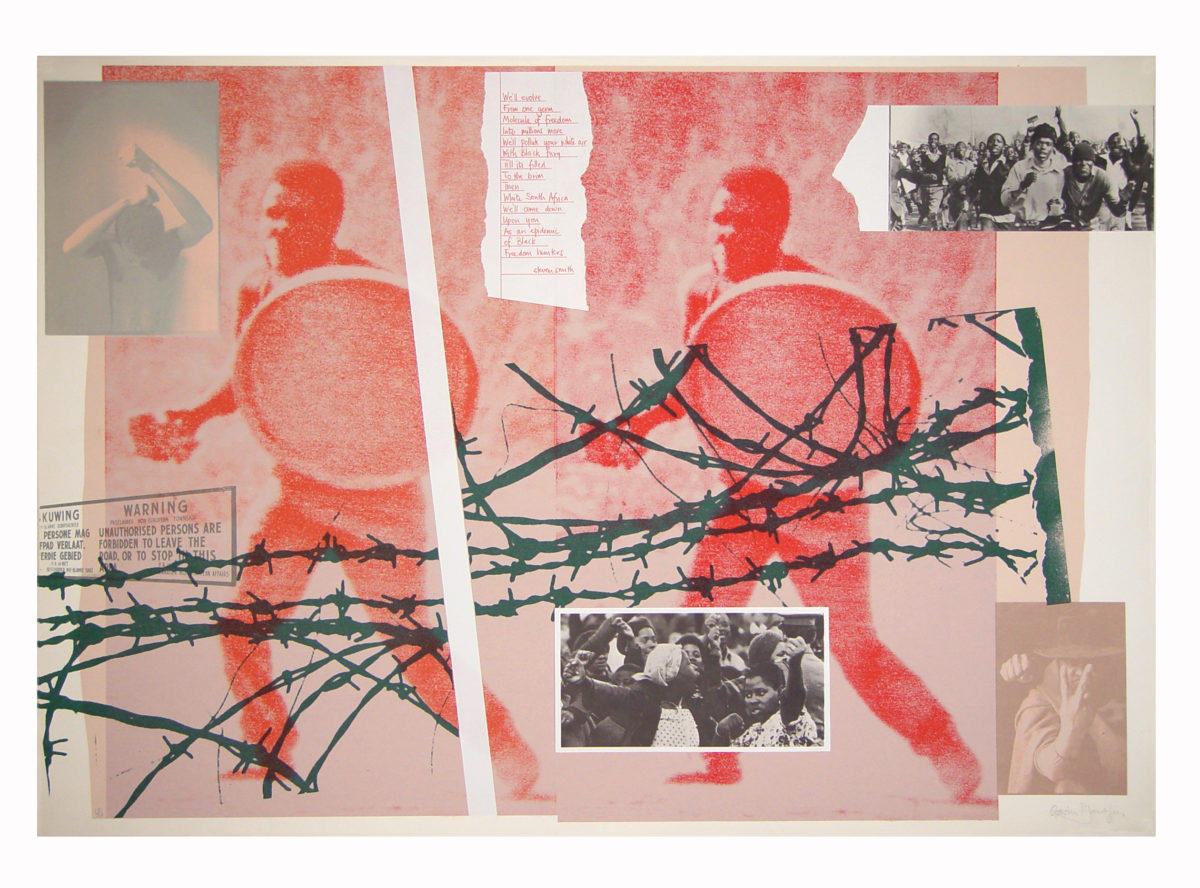

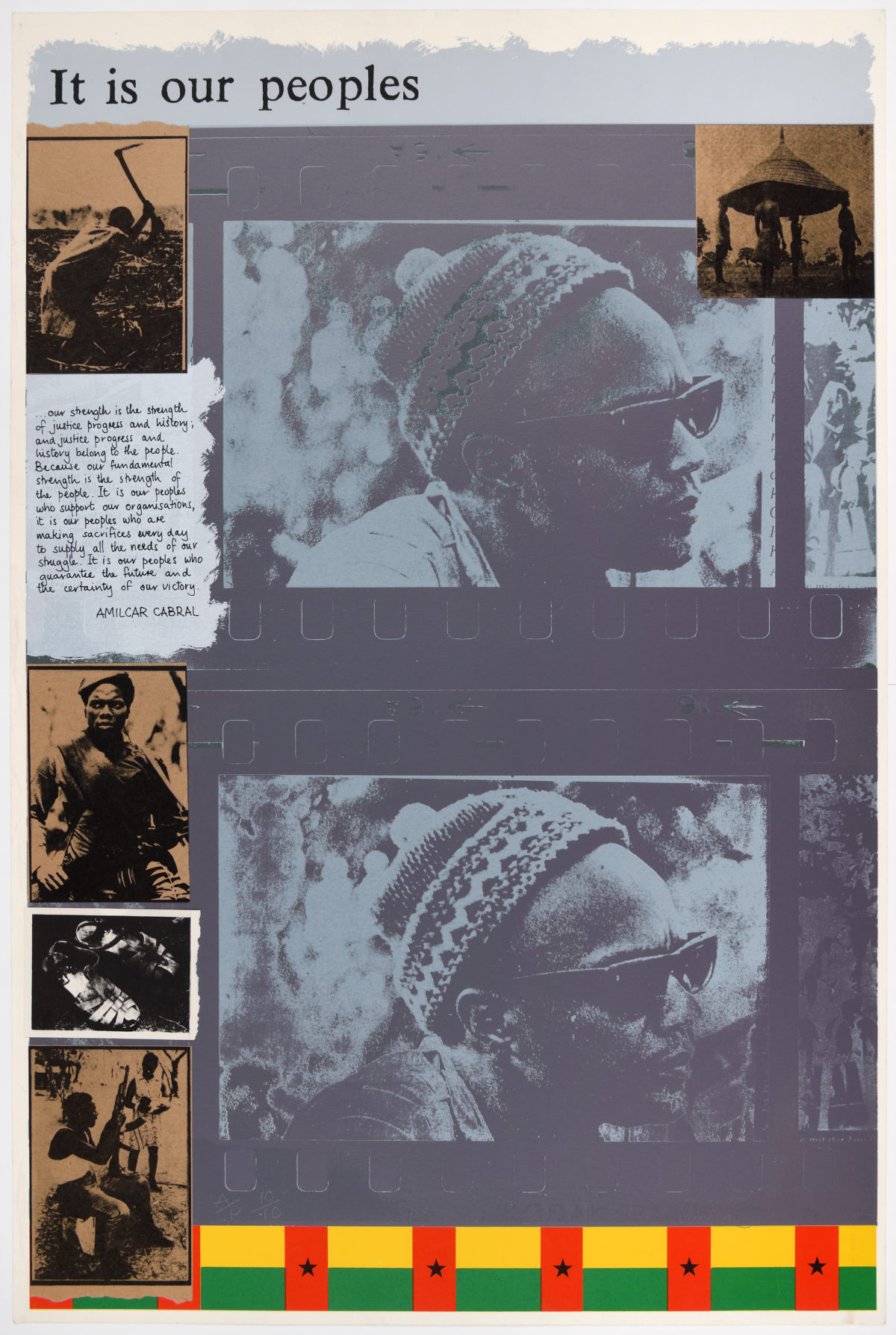

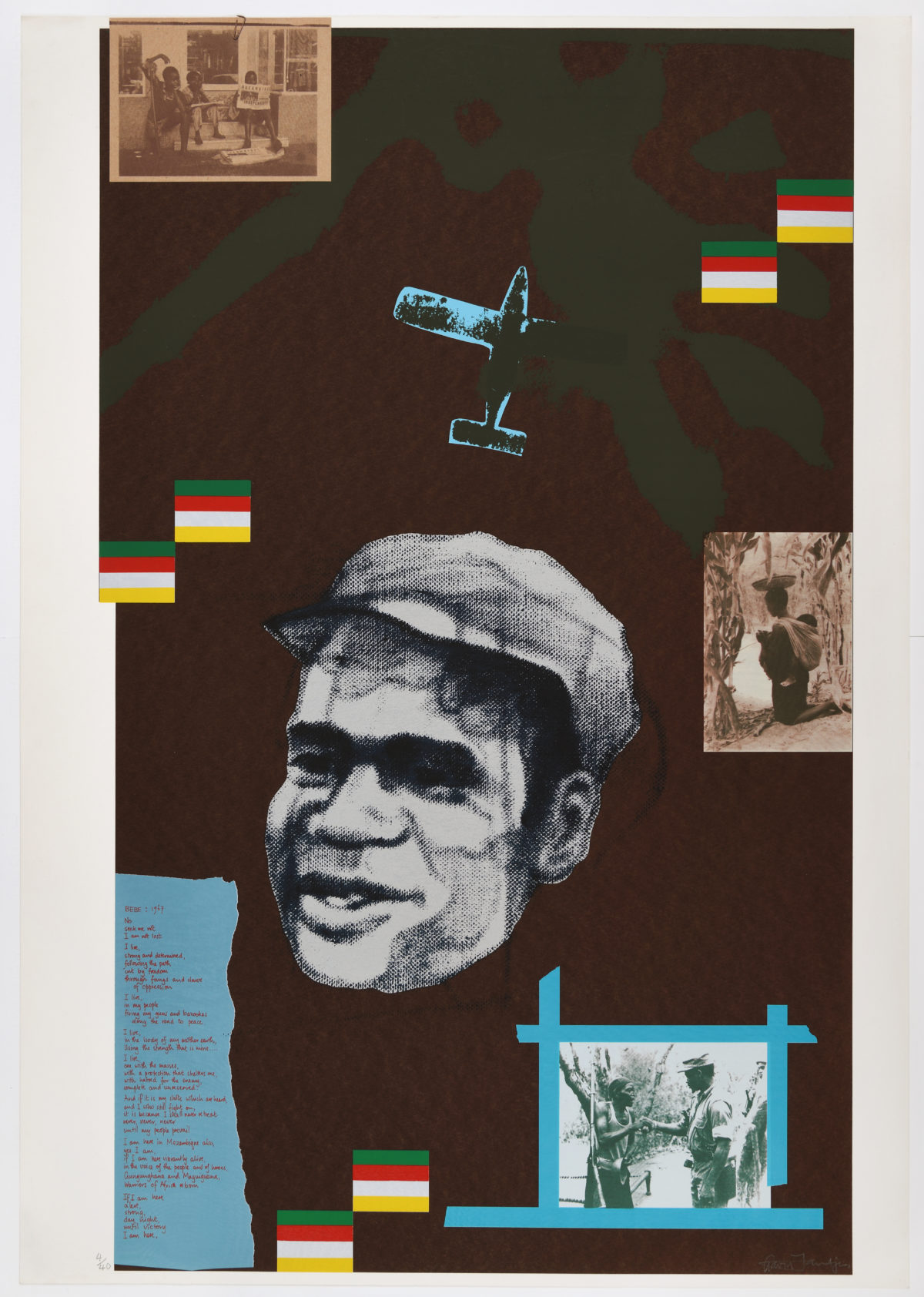

In the festival’s affiliated exhibition of South African art, held at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Botswana, Jantjes showed five works—including a print dedicated to Cabral alongside other images responding to the turmoil of apartheid. For Jantjes, these struggles were not unrelated, despite differing geopolitical conditions. Indeed, his early practice was clearly influenced by the ideas espoused by anti-colonial thinkers and leaders like Cabral—and Frantz Fanon, Eduardo Mondlane, and Kwame Nkrumah—whose writing, in turn, influenced the Black Consciousness movement and other anti-apartheid coalitions in South Africa. Exploring such connections through the artist’s work and writing, the present essay focuses on two screenprints that he created while in exile and presented in Gaborone—Freedom Hunters (1977; fig. 1) and It is our peoples (1974; fig. 2). The impact of Cabral’s theories on culture and revolution is evident in Jantjes’s multifaceted campaign in these years for what he termed “art for liberation’s sake.”5See, for instance, Gavin Jantjes: Graphic Work, 1974–1978, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Kulturhuset, 1978), 7, in which the artist writes: “The environments of today’s Africa demand liberation from inhumanity. Can the art of Africa ignore this demand? Can it be anything else than art for liberation’s sake?”

Born in District Six, Cape Town in 1948, Jantjes was one of the only non-white students to attend the Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town, where he studied graphic design in the late 1960s. However, as a student, he was subjected to increased surveillance and threats of punitive action—not just by educational authorities but also by officials of the apartheid state—on account of his outspoken politics. In the last year of his studies, Jantjes began to urgently seek asylum outside of South Africa. Finally, in 1970, he received a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) scholarship and secured a spot at the prestigious Hochschule für Bildende Künst in Hamburg.

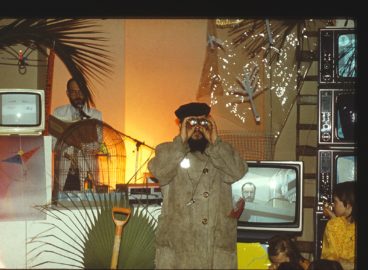

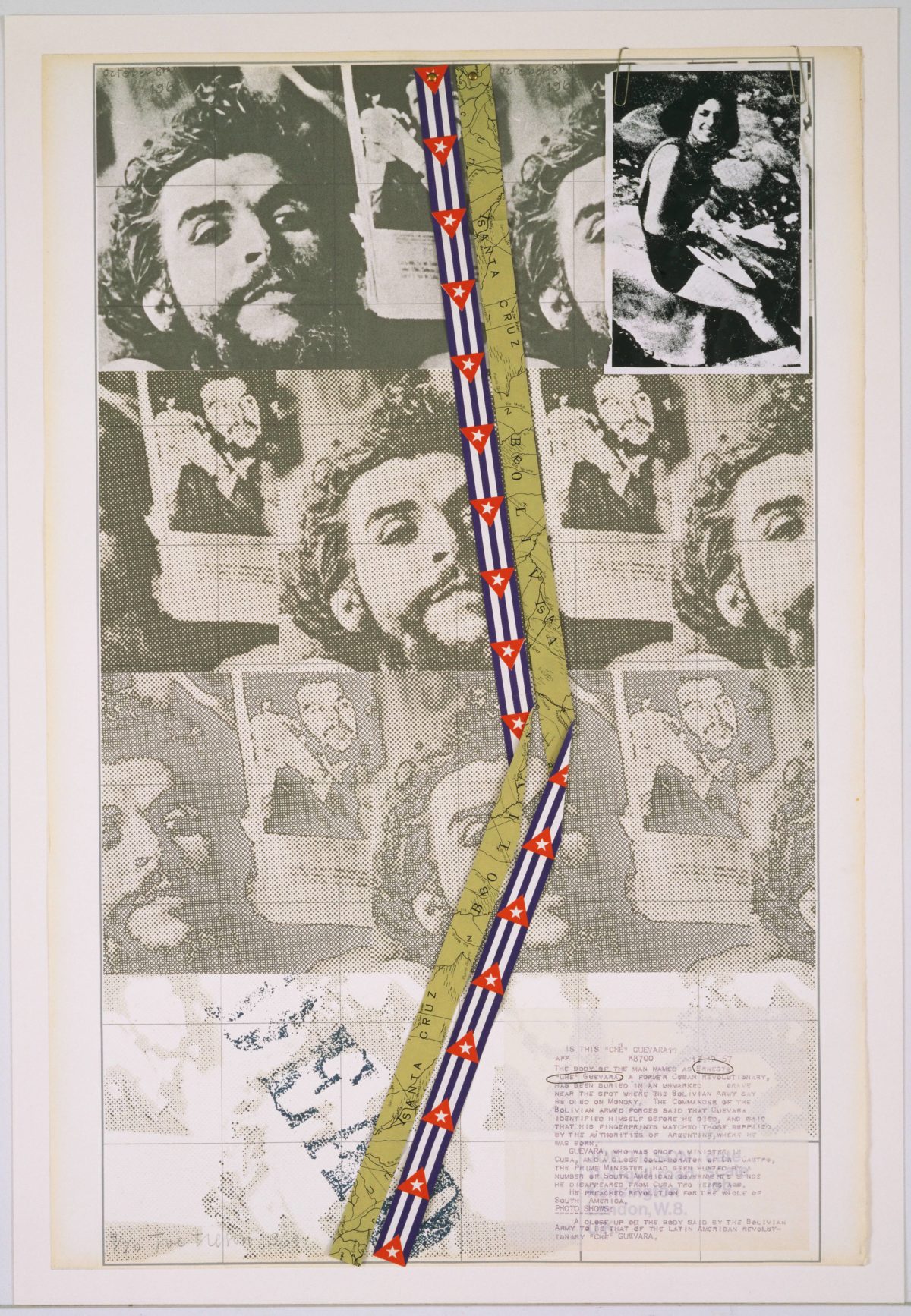

In Hamburg, Jantjes was mentored by artists such as Richard Hamilton (1922–2011), Joe Tilson (born 1928; fig. 3), and Joseph Beuys (1921–1986). Throughout the 1970s, he produced a prolific oeuvre of screenprints that combine archival and reportage photographs with quotations drawn from political theory, poetry, administrative records, and news articles. In each image, visual and textual passages are arranged as if torn from the pages of books or magazines and placed in dynamic juxtaposition to colorful Pop graphics. While reminiscent of the flatbed compositions common in much postwar art, Jantjes’s work departs from seemingly precedent works by Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) as well as Andy Warhol (1925–1987) in its expressly communicative purpose. Indeed, he wanted to make a tangible political impact, to educate viewers on the effects of colonization across the Global South. In his writing of the era, as in his art, Jantjes frequently argued that the times simply demanded that African artists directly engage with their political condition. He claimed in 1976, for instance, that “one cannot speak of form and colour when one’s environment speaks of poverty, hunger, and death.”6Exhibition statement and checklist for Gavin Jantjes: Screen Prints at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (April 6–May 2, 1976). Personal archive of Gavin Jantjes.

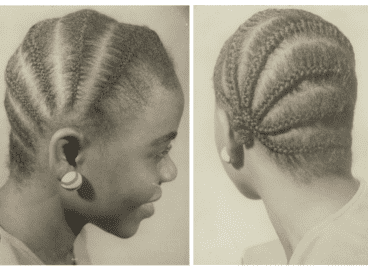

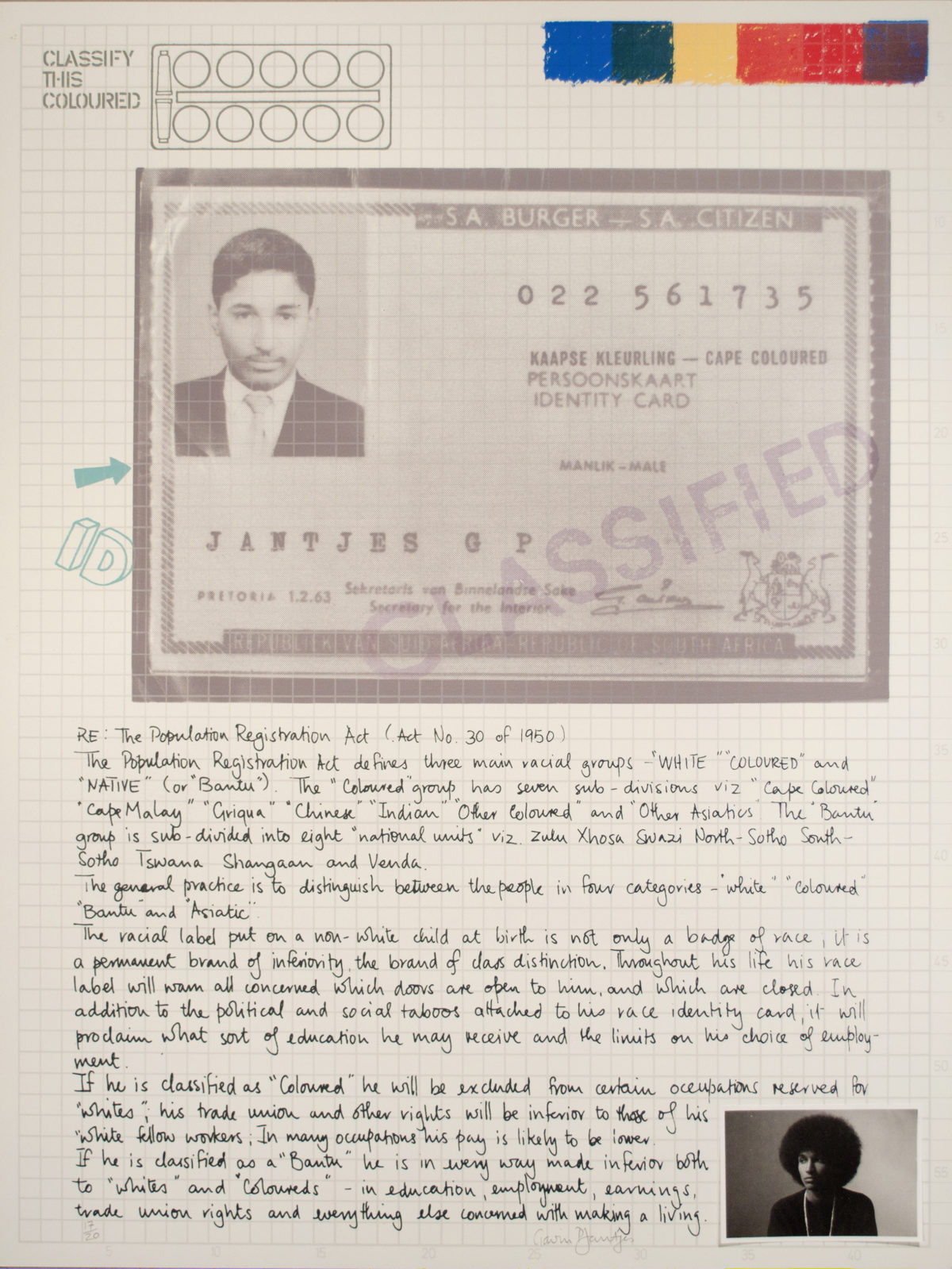

These values were first demonstrated in A South African Colouring Book—his earliest, and still most celebrated series of screenprints. Created in 1974–75, the suite consists of eleven images that convey different facets of the history and brutality of apartheid. It was motivated by Jantjes’s astonishment at his German peers’ lack of knowledge about the situation in South Africa. Deploying a motif evoking children’s educational materials, the prints capitalize on multiple associations implied through the use of the term “colour”—a reference to the legislation of racial identity under apartheid, for instance, or to his own designation within this system as “Cape Coloured” (evidenced by the inclusion of his own identification card in one print; fig. 4).

While living abroad, Jantjes had new access to information about anti-colonial and Pan-Africanist movements beyond South Africa. (Any speeches, news, or publications affiliated with such campaigns would have been censored by the apartheid state—although materials were still exchanged covertly among Black activist networks). In 1971, during his first year in Europe, Jantjes visited London, where he attended a public rally for Cabral. The artist was previously unfamiliar with Cabral’s revolutionary activism, and the speech made an enormous impression on him. Jantjes recalled, in particular, Cabral’s comments on the importance of language, and his democratic approach to providing political education to rural communities in Guinea Bissau. Cabral addressed individuals on the level of their own experience, rather than relying on the often-alienating parlance of academic theory. “When we began to mobilise our people,” he explained, “we couldn’t mobilise them for the struggle against imperialism—nor even, in some areas of Guiné, for the struggle against colonialism—because the people didn’t know what the words meant. . . . We had to mobilise our people on the basis of the daily realities of suffering and exploitation.”7Amílcar Cabral, “A question and answer session held in the University of London, 27th October, 1971,” in Our People Are Our Mountains, 22.

Jantjes took to heart the importance of communicating, plainly and simply, the brutal daily realities of colonized people across the world. After Cabral was assassinated by a political rival in 1973, Jantjes produced a print dedicated to his visionary leadership. Entitled It is our peoples, the work’s collagelike composition draws quotations from Revolution in Guinea: Selected Texts, a then-recent English-language publication of Cabral’s writing and speeches. The titular phrase, for instance, which appears in large type against a sky-blue banner, could have been lifted from any number of repeated incantations in a lecture that Cabral delivered in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: “[Our] fundamental strength is the strength of the people. It is our peoples who support our organisations, it is our peoples who are making sacrifices every day to supply all the needs of our struggle. It is our peoples who will guarantee the future and the certainty of our victory.”8Amílcar Cabral, “Opening address at the CONCP Conference held in Dar Es-Salaam, 1965,” in Revolution in Guinea: Selected Texts (London: Stage 1, 1970), 68.

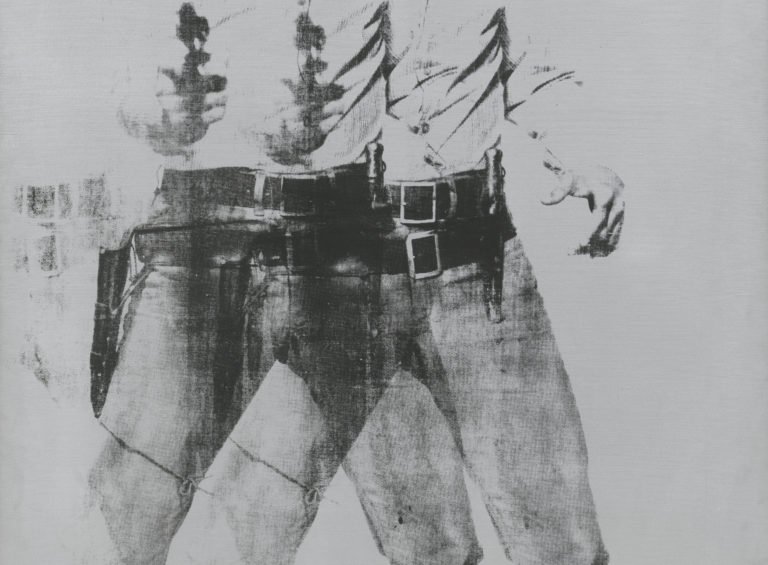

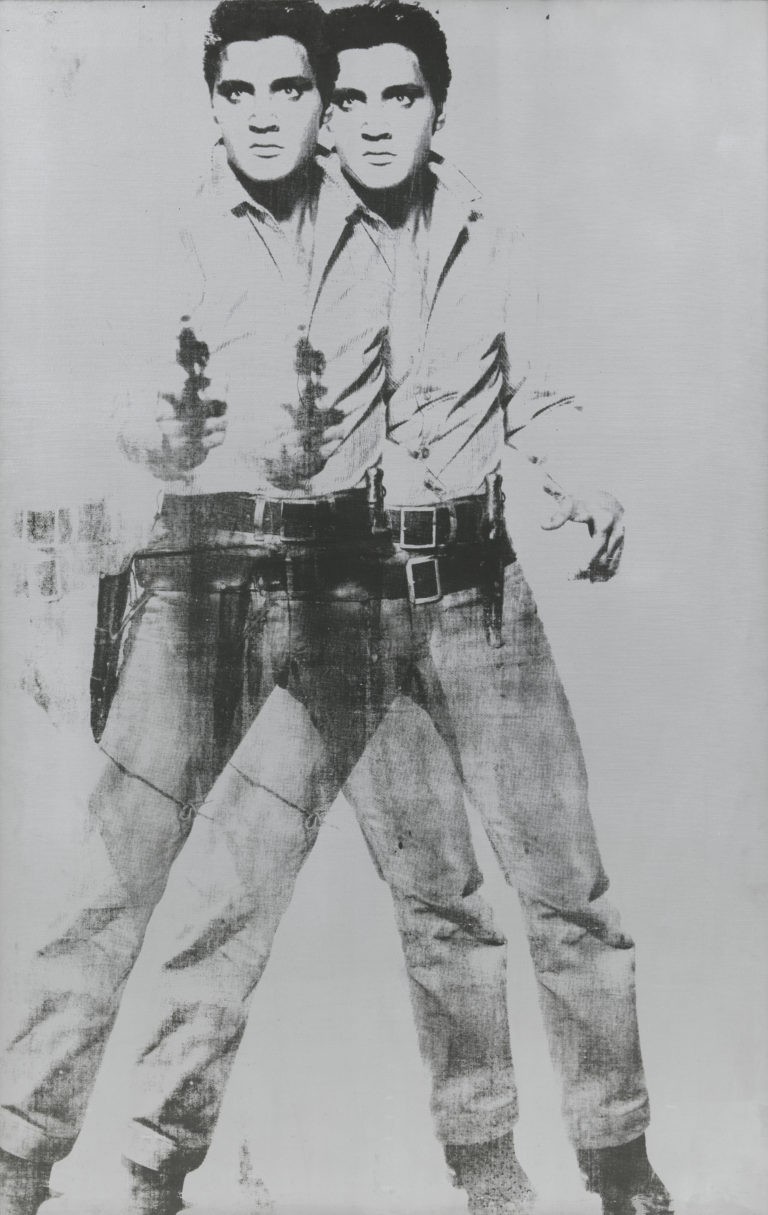

In the print, Jantjes has nestled this text alongside photographs of both daily life and military camps in Guinea. Among these images is a portrait of a PAIGC militant in uniform, screenprinted directly from the pages of Cabral’s publication Our People Are Our Mountains (1972)—in which an English translation of the London speech that Jantjes attended is reproduced.9Cabral, Our People Are Our Mountains, 2. One of the photographs reproduced in Jantjes’s image is printed on page 2 of the original publication, opposite the first page of “Speech made at a mass meeting in Central Hall, London, on 26th October 1971.” An original copy of this publication is available at Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA. These fragments surround a larger, solarized double-portrait of Cabral wearing his signature beanie and sunglasses. According to Jantjes, this is a photograph that he himself took of the television screen during a broadcast feature on the Guinean revolution. As such, the work is not simply an homage to Cabral’s leadership, but also a testament to the circulation and intermedial re-translation of material related to African politics—filmic negatives, for instance, that traveled from West Africa to the British press, as well as televised images made static through photographic capture, or the circulation of printed translations of words originally spoken impromptu before a crowded gathering. At the same time, Jantjes’s double-portrait of a recently-assassinated public figure clearly resonates with Warhol’s use of repetition to signal matters of real and symbolic death (or adjacency thereto) in his homages to Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy, and Elvis Presley (figs. 5 and 6), or to the victims of car accidents, penal execution, or riot police in America.10See Thomas Crow, “Saturday Disasters: Trace and Reference in Early Warhol,” Art in America Vol. 75, no. 5 (May 1987): 128-136.

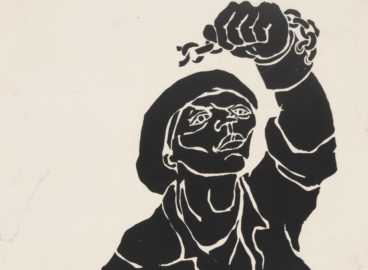

In the spring of 1976, this screenprint was among several shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in what was Jantjes’s first major solo exhibition.11Gavin Jantjes: Screen Prints was on view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, from April 6 to May 2, 1976. Included works drew content from a range of geopolitical contexts, from resistance efforts waged in Namibia to the American civil rights movement (fig. 7). But again, the artist cites Cabral. In his artist’s exhibition statement, Jantjes asserts that “we have to acknowledge through our creative expression that we are prepared to participate in the kenetic [sic] processes of culture and history,” before going on to quote Cabral, who once claimed: “The colonialists have a habit of telling us that when they arrived in Africa they put us into history. You are well aware that it’s the contrary—when they arrived in Africa they took us out of our own history.”12Cabral, “Speech made at a mass meeting in Central Hall, London,” 8.

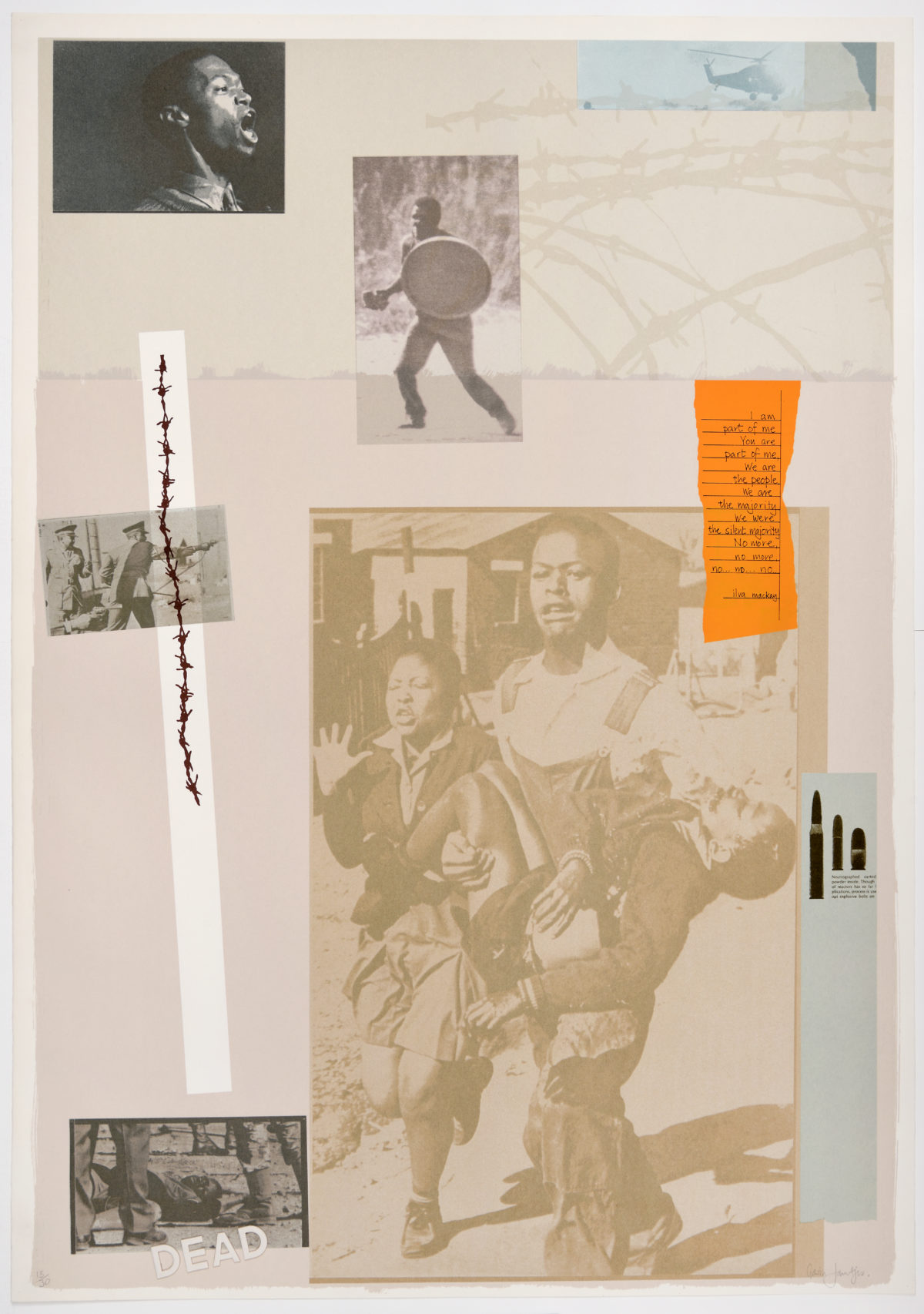

Jantjes was in London when the shocking news of an event now known as the Soweto uprising was relayed across the world. For several weeks, students in the South-Western Townships near Johannesburg peacefully protested the enforcement of Afrikaans as the mandated language of instruction in South Africa—a law that further disenfranchised the country’s African populations. On June 16, 1976, demonstrators were met by a militarized police force who opened fire on the crowd, killing and wounding countless children. For weeks, the front pages of international newspapers circulated the horrific photograph of the uprising’s first victim: thirteen-year-old Hector Pieterson, carried in the arms of a frightened classmate. Captured by Black South African photojournalist Sam Nzima, the iconic image swiftly became a symbol of apartheid violence. In a matter of months, Jantjes produced several screenprints about the Soweto uprising, including No More (1977; fig. 8), City Late 26 June 1976 (1977), and Freedom Hunters (1977; fig. 1).

The latter is among the most impactful of these works. Featuring a cropped and doubled detail from one of journalist Peter Magubane’s photographs of the event, it depicts students fighting bullets with stones and wielding the lids of trash bins as shields. While conveying, in part, the futility of the students’ defense against police artillery, these photographs also demonstrate their resilience in protesting the discriminatory society into which they were born. Set against a bright red backdrop, with an image of barbed wire bisecting the composition, Freedom Hunters communicates a sense of urgency and pleads with audiences to recognize and protest the violence of apartheid.

Such works resonate with the media-critical Pop practices of Joe Tilson and Richard Hamilton, with whom Jantjes studied, while demonstrating the artist’s own belief in the political responsibility of post- and anti-colonial artists.13For information on the influence of Pop art precedents on Jantjes’s stylistic strategies, see Allison K. Young, “Visualizing Apartheid Abroad: Gavin Jantjes’s Screenprints of the 1970s,” Art Journal 76, no. 3–4 (2017): 10–31; and Amna Malik, “Gavin Jantjes’s A South African Colouring Book,” in The Place is Here: The Work of Black Artists in 1980s Britain, ed. Nick Aikens and Elizabeth Robles (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2019): 161–90. As Cabral explained, the fight to reclaim one’s culture, history, and identity was as crucial to liberation struggles as the fight for legal rights. The students of Soweto demonstrated this same desire when they petitioned for an equal education. In fact, these protests were orchestrated by the South African Students’ Movement (SASM), an affiliate of Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness movement—and Biko is well documented as having been impacted by Cabral’s activism.14See, for instance, mention of the circulation of Cabral’s (and other African leaders’) writings in South Africa in Shannen L. Hill, Biko’s Ghost: The Iconography of Black Consciousness (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015): 1. Hill cites, as well, sources such as C. R. D. Halisi, Black Political Thought in the Making of South African Democracy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999). The connections among Black liberation leaders are also made explicit in material related to the 2007 exhibition Biko: The Quest for a True Humanity at the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa; see https://www.apartheidmuseum.org/uploads/files/BIKO-1b.pdf. Jantjes’s familiarity and alignment with such political and intellectual networks is evident in the boldly didactic style of his early practice, and in his attention to globalized circulations of political theory. In documenting the South African struggle in connection to other struggles being waged across the continent, Jantjes raised awareness and helped galvanize support for anti-colonial causes worldwide.

It is our peoples and Freedom Hunters were both on view in Gaborone during the 1982 Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival—a gathering of cultural workers invested in parsing matters of art, education, and activism. The event drew delegates from every region of South Africa, and from exile across the world, to Botswana; leading voices such as Mongane Wally Serote, Hugh Masekela, Nadine Gordimer, David Goldblatt, and Keorapetse Kgositsile were among those who debated the role of culture in the ongoing struggle for liberation. Most participants, like Jantjes, believed strongly that art would remain intertwined with politics as long as the freedom struggle remained urgent. Gordimer declared, for instance, that “if you are a committed artist you are committed to using your talents to service the cause of justice,”15As quoted in “Time to think of a post-apartheid culture.” Source publication and masthead not preserved. Press clipping, UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archive at the University of the Western Cape, Cape Town (hereafter Mayibuye Archive), MCH233-CAIC-1-14. while actor Zakes Mofokeng told peers that “trying to avoid politics in art is like trying to dodge raindrops on a rainy day.”16As quoted in Tony Weaver, “Art to be used in the liberation struggle,” Sunday Times (Johannesburg), July 11, 1982. Press clipping, Mayibuye Archive, MCH233-CAIC-1-12.

While the symposium and festival lasted just a week, the event was accompanied by a two-month-long exhibition of South African art at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Botswana. Entitled Art Toward Social Development, and like the symposium and festival with which it coincided, it was one of the first and most significant occasions in which the work of both exiled and South African–based visual artists was displayed together in a “non-racial” exhibition—which, in the era’s parlance, meant it included work by South Africans classified as “black, coloured, or white” by the apartheid state. The organizers sought to represent the “entire spectrum of South African society” and to reflect a “panorama” of the nation’s creative activity.17Pamphlet and checklist for “Art Toward Social Development: An Exhibition of South African Art,” held June 10–August 10, 1982, at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Botswana. Mayibuye Archive, MCH233-CAIC-1-5. Significantly for Jantjes, who had not lived in his home country for more than a decade, the exhibition marked his inclusion within an emerging canon of anti-apartheid art, alongside compatriots Ezrom Legae (1938–1999), Lionel Davis (born 1936), David Koloane (1938–2019), Durant Sihlali (1935–2004), David Goldblatt (1930–2018), and Sue Williamson (born 1941), among others.

By the time of his participation in Art Toward Social Development, Jantjes was at the precipice of a major shift in style, artistic focus, and professional milieu. He moved to the United Kingdom in August 1982, and began to paint. His Korabra series, completed in 1986, comprised several large-scale acrylic paintings—texturized with sand embedded in pigment—that ruminate on the history of transatlantic slavery.18For more information on this series, see David Dibosa, “Gavin Jantjes’s Korabra Series (1986): Reworking Museum Interpretation,” in “Rethinking British Artists and Modernism,” special issue, Art History 44, no. 3 (June 2021): 572–93. Jantjes became increasingly interested in ancestral arts of Africa, including West African sculpture, Egyptian monuments, and Khoisan rock paintings (fig. 9). His interest in the latter, for instance, gave rise to a series of prints, paintings, and mixed-media works that overlay esoteric prehistoric imagery with indigo night skies shimmering with constellations and galactic haze. Mixed-media works such as Untitled (double canvas with sculptures) (1988; fig. 10) are remarkably enigmatic; the mystical imagery of stylized masks, natural materials including twigs, and abstracted ceramic ovoid and cubic forms make this piece virtually unrecognizable in relation to Jantjes’s polemical print practice of the 1980s. In an untitled painting from 1989 (fig. 11) , the artist paired the same mask motif—whose sharp, elongated contours are reminiscent of art produced by the Fang peoples of Gabon—with a female figure from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). Such works aim to uplift the status of African art, which has so often been pushed to the peripheries while European modernists appropriated their forms.

The seeds of these later artistic inquiries are, indeed, detectable in the speech that Jantjes delivered in Gaborone, in which he made the case for centering African art in Western art education. In this presentation, he echoed Cabral’s reminder that the colonists in Africa “took us out of our own history” and honored the Soweto students’ aspirations for an Afrocentric pedagogy: “Visual art education must work to eradicate the interiorization of the western evaluation of our contemporary art. It should instil [sic] in our people a meaningful interest in their culture and art and move them to recognise these as an integral part of the nations [sic] struggle against racist domination.”19Jantjes, “The role of the visual artist,” 3.

In his practice both in and out of the studio, Jantjes fought for the decolonization of culture and education, so as to ensure that future generations would have access to African history and identity. Drawing from references to Cabral and Biko, Warhol and Tilson, he grounded this effort in his faith in the power of collectivity and global solidarity.

- 1The Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival was held in Gaborone, Botswana, from July 5 to July 9, 1982. It was organized by members of the Medu Art Ensemble, a collective of exiled South African artists, poets, and writers based in Botswana, in affiliation with the African National Congress. The gathering’s significance is due, in part, to its assembling of cultural workers based in South Africa as well as living in exile across the world.

- 2For more on the Medu Art Ensemble, see Clive Kellner, “Culture as a Weapon of Struggle: The Art of the Medu Poster You Have Struck a Rock (1981),” post: notes on art in a global context, September 15, 2021, https://post.moma.org/culture-as-a-weapon-of-struggle-the-art-of-the-medu-poster-you-have-struck-a-rock-1981/.

- 3Gavin Jantjes, “The role of the visual artist,” July 1982 (exact date unknown), Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival, Gaborone, Botswana; transcribed in Gavin Jantjes, “The role of the visual artist,” Artrage: Inter-Cultural Arts Magazine no. 2 (February 1983): 2–3.

- 4Ibid., 2. The quote is not attributed therein, but rather in Amílcar Cabral, “Speech made at a mass meeting in Central Hall, London, on 26th October 1971,” in Our People Are Our Mountains: Amílcar Cabral on the Guinean Revolution (London: Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola & Guiné, 1972), 8.

- 5See, for instance, Gavin Jantjes: Graphic Work, 1974–1978, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Kulturhuset, 1978), 7, in which the artist writes: “The environments of today’s Africa demand liberation from inhumanity. Can the art of Africa ignore this demand? Can it be anything else than art for liberation’s sake?”

- 6Exhibition statement and checklist for Gavin Jantjes: Screen Prints at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (April 6–May 2, 1976). Personal archive of Gavin Jantjes.

- 7Amílcar Cabral, “A question and answer session held in the University of London, 27th October, 1971,” in Our People Are Our Mountains, 22.

- 8Amílcar Cabral, “Opening address at the CONCP Conference held in Dar Es-Salaam, 1965,” in Revolution in Guinea: Selected Texts (London: Stage 1, 1970), 68.

- 9Cabral, Our People Are Our Mountains, 2. One of the photographs reproduced in Jantjes’s image is printed on page 2 of the original publication, opposite the first page of “Speech made at a mass meeting in Central Hall, London, on 26th October 1971.” An original copy of this publication is available at Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

- 10See Thomas Crow, “Saturday Disasters: Trace and Reference in Early Warhol,” Art in America Vol. 75, no. 5 (May 1987): 128-136.

- 11Gavin Jantjes: Screen Prints was on view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, from April 6 to May 2, 1976.

- 12Cabral, “Speech made at a mass meeting in Central Hall, London,” 8.

- 13For information on the influence of Pop art precedents on Jantjes’s stylistic strategies, see Allison K. Young, “Visualizing Apartheid Abroad: Gavin Jantjes’s Screenprints of the 1970s,” Art Journal 76, no. 3–4 (2017): 10–31; and Amna Malik, “Gavin Jantjes’s A South African Colouring Book,” in The Place is Here: The Work of Black Artists in 1980s Britain, ed. Nick Aikens and Elizabeth Robles (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2019): 161–90.

- 14See, for instance, mention of the circulation of Cabral’s (and other African leaders’) writings in South Africa in Shannen L. Hill, Biko’s Ghost: The Iconography of Black Consciousness (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015): 1. Hill cites, as well, sources such as C. R. D. Halisi, Black Political Thought in the Making of South African Democracy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999). The connections among Black liberation leaders are also made explicit in material related to the 2007 exhibition Biko: The Quest for a True Humanity at the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa; see https://www.apartheidmuseum.org/uploads/files/BIKO-1b.pdf.

- 15As quoted in “Time to think of a post-apartheid culture.” Source publication and masthead not preserved. Press clipping, UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archive at the University of the Western Cape, Cape Town (hereafter Mayibuye Archive), MCH233-CAIC-1-14.

- 16As quoted in Tony Weaver, “Art to be used in the liberation struggle,” Sunday Times (Johannesburg), July 11, 1982. Press clipping, Mayibuye Archive, MCH233-CAIC-1-12.

- 17Pamphlet and checklist for “Art Toward Social Development: An Exhibition of South African Art,” held June 10–August 10, 1982, at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Botswana. Mayibuye Archive, MCH233-CAIC-1-5.

- 18For more information on this series, see David Dibosa, “Gavin Jantjes’s Korabra Series (1986): Reworking Museum Interpretation,” in “Rethinking British Artists and Modernism,” special issue, Art History 44, no. 3 (June 2021): 572–93.

- 19Jantjes, “The role of the visual artist,” 3.