In this essay, Māra Traumane guides readers through the diverse, interdisciplinary practice of the Riga-based collective Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings (NSRD), which operated from the end of the 1970s until 1989. NSRD was involved in the avant-garde music scene as well as in architecture, and their activities ranged from concerts and the production of record albums to performances, writing, and video art. From consciously exploring the notion of periphery to developing the concept of “Approximate Art,” the group sought to question and escape disciplinary boundaries and divisions.

Over the last three decades, the notion of periphery and conceptualization of center-periphery relations have been actively explored by scholars and curators working on Eastern European histories of art. The terms “periphery” and “margins” have been applied in this context as productive concepts invigorating methods of critical geography and strategies of “provincializing” dominant artistic canons coined at alleged centers.1Piotr Piotrowski, “On the Spatial Turn, or Horizontal Art History,” Umeni / Art 56, no. 5 (2008): 378–83. Recent research has proposed a critique of the binary logic and directionality of the center-periphery model, challenging the legitimacy of a “a preconceived notion of centrality”2Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, “Provincializing Paris. The Center-Periphery Narrative of Modern Art in Light of Quantitative and Transnational Approaches,” in “Spatial (Digital) Art History,” special issue, Artl@s Bulletin 4, no. 1 (2015): 61. and inviting reconsideration of cultural phenomena within geographically peripheral milieus as active agents in cultural entanglements.3Tomasz Grusiecki, “Uprooting Origins: Polish-Lithuanian Art and the Challenge of Pluralism,” in Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present, ed. Beáta Hock and Anu Allas (London and New York: Routledge, 2018), 25–38. Yet even before the notion of periphery became an urgent topic in art historical theorization and discussions, it was both actively and implicitly addressed by artistic practices emerging in Eastern Europe in the 1970s and 1980s that explored geographic peripheries through performance actions and drew attention to processes of perception activated by artistic actions conceived in off-center locations.

Possibly one of the best documented and most researched examples of such an approach is the work of the Moscow–based Collective Actions Group, which beginning in 1976 and continuing for more than a decade, carried out a series of actions in Kievogorskoe Field outside of Moscow. In their extensive discussions of and writings on their outdoor actions, the group introduced a number of original topographic and perceptual terms—including “zone of indistinguishability,” the moment, when performers of an action appear in the field of vision of spectators but are still too distant for details of their activity to be distinguishable, and “demonstrational field,” which describes apprehensible arrangements and settings, as well as the course of an action and its perceptive effects.4See Claire Bishop, “Zones of Indistinguishability: Collective Actions Group and Participatory Art,” e-flux Journal, no. 29 (November 2011), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/29/68116/zones-of-indistinguishability-collective-actions-group-and-participatory-art/. See also Andrei Monastyrsky, ed., Poezdki za gorod: Kollektivnye deistvia [Trips out of Town. Collective Actions] (Moscow: Ad Marginem, 1998), 19–24. Other examples are the collective exploratory walks and happenings undertaken in neglected urban areas in the 1970s by a group of Tallinn architects and artists who drew inspiration from city outskirts and urban sites “forgotten by modernization.”5See Mari Laanemets, Zwischen westlicher Moderne und sowjetischer Avantgarde: Inoffizielle Kunst in Estland, 1969–1978 (Berlin: Gebruder Mann Verlag, 2011), 123–24. Author’s translation unless otherwise indicated. Likewise, in the 1980s, peripheral environments and ambient, borderline modes of perception were actively explored by the Riga–based artists’ group Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings (Nebijušu sajūtu restaurēšanas darbnīca, or NSRD). Members of this transmedia collective brought semi-abandoned sites and other transitional spaces—city outskirts and railway lines—as well as unspectacular daily events, marginal gestures, and multisensory perceptive states into focus in their early writings, and these interests later played a key role in the actions and video-performances undertaken by the group. In the late 1980s, in the last years of their collaboration, NSRD members outlined their aesthetic engagement with peripheral processes and transitory states of perception in their “Manifesto of Approximate Art” and three accompanying essays, all of which were written in 1987.6Hardijs Lediņš and Juris Boiko, “Aptuvenās mākslas manifests” [Manifesto of Approximate Art, 1987], “Sarunas ar Mikiju Rēmanu. Pirmā” [Conversations with Micky Remann: The First, 1987], and “Sarunas ar Mikiju Rēmanu. Otrā” [Conversations with Micky Remann. The Second, 1987]. These manuscripts are held in the Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga. They are reprinted and translated into English in Ieva Astahovska and Māra Žeikare, eds., Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings: Juris Boiko and Hardijs Lediņš (Riga: Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2016), 222–27. Hardijs Lediņš, “Auf dem Weg zu Ungefähren” [On the Way to the Approximate], in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde, exh. cat. (Berlin: Elefanten Press, 1988), 71–73; reprinted and translated into English in ibid. 220–21.

The Workshop

NSRD, formally founded as a music group in 1982, was an association of friends active in Latvia—then a republic of the Soviet Union—from the end of the 1970s until 1989. Long-term members included architecture theorist Hardijs Lediņš (1955–2004), poet and translator Juris Boiko (1954–2002), architect Imants Žodžiks (born 1955), musician Inguna Černova (born 1962), and architect Aigars Sparāns (1955–1996), but on many occasions, this core group was joined by a wider circle of collaborators.7Occasionally, the core group was joined by artist Leonards Laganovskis (born 1955), musicians Mārtiņš Rutkis (born 1957), Nils Īle (born 1968), and Roberts Gobziņš (born 1964), and performer Dace Šēnberga (born 1967), among others. NSRD member activities extended across a variety of media, including poetry, song lyrics and collaborative writing, new-wave and experimental music recordings, architectural proposals, actions realized outdoors in both nature and urban spaces, and in the second half of the 1980s, multimedia exhibition events, performances, and video-performances. Although the name “Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings” initially described the group’s activities in the field of music and, later, in visual art, it is now considered more of an umbrella term covering the entire scope of the collaboration. Collective ways of working, the original aesthetic program developed by the group, and their interest in the creation of time-based aesthetic experiences and pursuit of “a philosophical process,”8Hardijs Lediņš, “HL:NL,” interview by Normunds Lācis, Avots, no. 4. (1988): 52; reprinted and translated into English in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 139–48, 142. invite comparison to other collectives originating in the 1960s and 1970s in Eastern Europe, including the Slovenian group OHO and the Moscow–based Collective Actions Group.

Given the diversity and experimental nature of NSRD’s activities, one might question how it was possible for the artists to carry out their practice in the Soviet Union, where until the mid-1980s, the cultural field was not only subject to rigid ideological control but also opportunities for public artistic expression were mainly given to members of official unions of creative workers, or to those affiliated with amateur clubs. Indeed, some of NSRD’s activities in the first half of the 1980s, for example their outdoor actions, were carried out without an audience—that is, with only members of the collective present. This is why NSRD has sometimes been described as an “unofficial” or even “nonconformist” art phenomenon. However, this characterization is only partially fitting, because even in the early 1980s, within the daunting climate of the Brezhnev era, members of NSRD found opportunities to present their work and aesthetic interests to a wider audience. For example, for recording and distributing their music albums, the artists relied on friendships with other semiofficial music bands and on an expanding network of underground tape-recording culture.9See Daiga Mazvērsīte and Māra Traumane, “Avant-garde Trends in Latvian Music, 1970s–1990s / Avantgardistische Strömungen in der Lettischen Musik von 1970–1990,” in Sound Exchange: Experimental Music Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe / Experimentelle Musikkulturen in Mitteleuropa,ed. Carsten Seiffarth, Carsten Stabenow, and Golo Föllmer (Saarbrücken: Pfau Verlag 2012), 239–44, 253–58, http://www.soundexchange.eu/#latvia_en?id=43. NSRD recordings are accessible on the Pietura nebijušām sajūtām website, www.pietura.lv. There were also institutional niches that enabled the artists to revise and present their ideas in exhibition spaces in Latvia. Several NSRD members were professionally trained architects and also members of the Architects’ Union of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic. Between 1980 and 1985, annual exhibitions of experimental projects by young architects, organized by the Architects’ Union, served as frameworks for the public display of inventive conceptual proposals by NSRD members related to the organization of space and living environments.

The ongoing presence of NSRD in public and semipublic spheres raises questions regarding the distinction between the “first,” or official public sphere, and the “second,” or alternative or unofficial public sphere—categorizations that are sometimes used in descriptions of the cultural environment in the Communist bloc.10Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak, introduction to Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-based Art in Late Socialist Europe, ed. Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak (New York and Oxon: Routledge 2018), 1–16. Instead, attention should be drawn to the loopholes, structural gaps, and individual agendas that permeated the cultural field at that time, interrupting the controlling regimes of state institutions and facilitating visibility of independent initiatives such as NSRD.

Peripheries as Sites of Action

“There can’t be such a thing as a center of culture, there can only be a periphery of culture,” NSRD cofounder Juris Boiko pronounced in an interview published in 1988.11Eckhart Gillen, “Ungefähre Kunst in Riga. Gespräch zwischen der Werkstatt zur Restauration nie verspürter Empfindungen und Eckhart Gillen” [Approximate Art in Riga: Conversation between “Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings” and Eckhart Gillen], Niemandsland. Zeitschrift zwischen den Kulturen 5 (1988): 33; reprinted and translated into English in abridged form in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 260. While the group was active, their interest in peripheral spaces and multisensory experience manifested in a variety of genres and media—in literary writings, actions, experimental music recordings, conceptual architectural proposals, and video-performances. In their practice, the notion of “periphery” evolved from its role as a site of physical immersion, contemplation, and performance action to a more productive notion related to the multisensorial contingency of human perception. As Hardijs Lediņš and Boiko outline in the group’s “Manifesto of Approximate Art”: “We identify ourselves with borders. We orientate ourselves in the relationships between the center and the periphery. The processes of identification and orientation lead and guide all our activities.”12Lediņš and Boiko, “Manifesto of Approximate Art” (1987); reprinted and translated into English in ibid., 227.

Themes of immersive wandering through a desolate, semi-abandoned landscape permeate the absurd novel Zun (the title referencing both “Zen” and the Latvian word for “buzzing”), cowritten by Lediņš and Boiko in 1976–77 and not published until 2005.13The original text is preserved in sixteen typewritten notebooks now held in the Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga. In this early text oscillating between poetry and prose, and reflecting the influence of writings by Dada artist Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948) and American poet E. E. Cummings (1894–1962), lonely protagonists traverse a snowy rural landscape, each engaged in solitary action and random, fleeting encounters with other human and nonhuman beings. Programmatic in structure, Zun sketches out the themes of atmospheric wandering in nature and contemplative perceptive states that would characterize the future practice of NSRD.

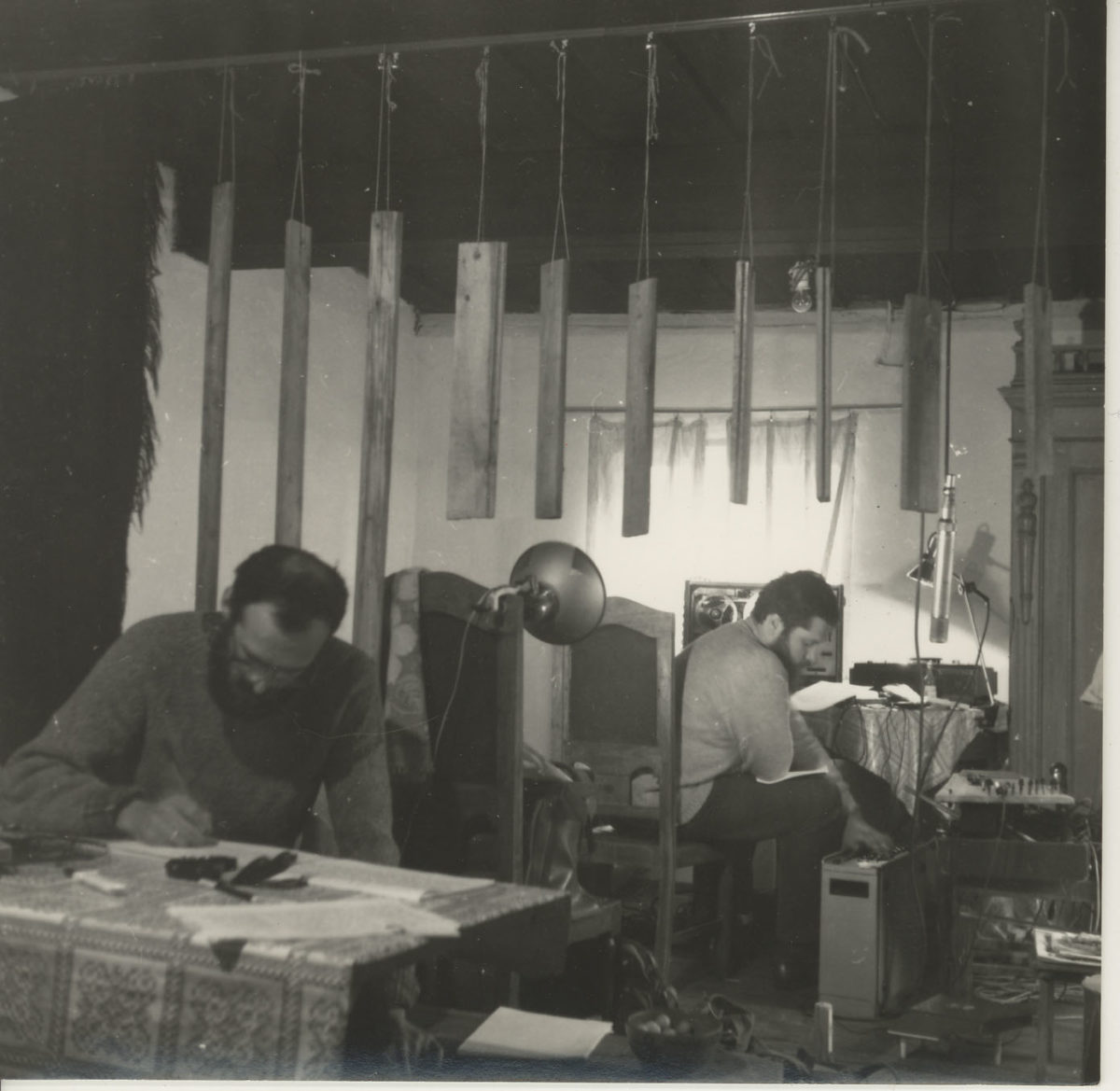

At the time Lediņš and Boiko were writing Zun, and in the years after, they and other members of NSRD were influenced not only by Dada and the artistic avant-garde but also by the musical avant-garde, most notably the Second Viennese School, new jazz, John Cage (1912–1992), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007), and minimalist music. The ideas the group discovered in new music informed their own DIY recording sessions as well as their outdoor actions. Retrospectively, Boiko recalled that NSRD’s actions in the early 1980s can be seen as a “transposition” of the impulses they found in avant-garde music into the surrounding environment. Indeed, Cage’s ideas about silence as well as Stockhausen’s improvisational principles and intuitive music echo in the structure of one of the group’s most extensive cycles of actions: Walks to Bolderāja (Gājieni uz Bolderāju, 1980–87). In this particular work, NSRD addressed notions of geographically peripheral zones and changing modes of perception through ritual-like “walks” undertaken at dawn or dusk, once a year, each time in a different month, along the twelve-kilometer-long railway line connecting the outskirts of Riga, where the participating artists lived, with the distant port district of Bolderāja. Along their path, which took them across meadows and fields to the industrial surroundings of Bolderāja, they observed the changing landscape and weather, and the breaking or fading daylight—as well as interacted with objects they found along the way and the soundscape of the railway line—the rumble of passing trains and their own musical interventions. As was characteristic of their practice, the group captured the ambience and experiences of the “walks” in photo and video documentation of the action, and in other mediums, including in lyrics and music recorded on the album Bolderāja’s Style (Bolderājas stils), which they released on their own home-record label Seque in 1982.

The group also drew attention to neglected territories and vernacular suburban structures through conceptual architectural proposals, which members submitted to annual exhibitions at the Architects’ Union of experimental projects by young architects. In these submissions, conceived as creative responses to the general themes of the exhibitions, they presented conceptual interpretations of particular spatial situations—rather than practical architectural solutions. For example, the photo-montage Spatial Action 1m x 1m x 1m (Telpiska akcija 1m x 1m x 1m), which the artists presented in the exhibition Foregrounds of Architecture (1980), is made up of a sequence of photographs of Hardijs Lediņš and Imants Žodžiks excavating a one-meter-square hole in a stretch of land alongside a Soviet concrete wall and the corner of an old wooden building typical of the area. This ironic take can be seen as targeting both formal submission requirements—the standard one-by-one-meter architectural board, and the neglected state of the urban periphery. In 1984, in a submission to the exhibition Nature—Home to Man, the group integrated photographs taken during a Walk to Bolderāja action called A House in Bolderāja (Māja Bolderājā), in which Lediņš engaged with derelict allotment garden sheds and greenhouse structures situated along the railway line. In both proposals, the artists directed attention toward the unspectacular, marginal, vernacular spaces and architectural forms that were given visibility through their own performative gestures.

From Postmodernism to Approximate Art

Postmodernist theory and the aesthetics of new-wave culture played crucial roles in the development of the artistic language of NSRD in the mid-1980s—following the group’s interest in the legacy of the modernist avant-garde. Postmodernism, which the artists first encountered through architecture and design theory, in particular the publications of Charles Jencks (1839–2019) and Alessandro Mendini (1931–2019), proposes an alternative to the prevalent uniform functionalism that some members of NSRD were confronted with as architects working for state-run construction bureaus and thus provided the basis for the group’s critique of standardization in architecture and design. Charles Jencks’s thesis on “double coding” was appropriated as a programmatic statement by Lediņš who, in numerous articles dedicated to architecture and art, writes about “the spirit of the time and atmosphere of place,”14Hardijs Lediņš, “Zeitgeist und geistige Toposphäre / Laika gars un vietas atmosfēra” [The Spirit of Time and Atmosphere of Place], in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde 30, 79; reprinted and translated into English in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 439–40. meaning the search for a balance between technological and stylistic innovation and the traditional cultural “code” embedded in the specificity of a site. Postmodern use of narrative and semantic forms, abolishment of a distinction between “high” and popular culture, multimediality, irrationality, and emphasis on atmosphere of a particular site and individual expression resonated with the group’s interest in music, design, art, and architecture. At the same time, they drew inspiration from contemporary trends in music—from ambient music and the work of Laurie Anderson (born 1947) and Philip Glass (born 1937) integrating poetic narrative structures into multimedia performance events. In 1985, NSRD recorded what would be considered one of their musical masterpieces—the conceptual sound-play Kuncendorfs and Osendovskis (Kuncendorfs un Osendovskis), a sonic tale in which the narrative plot and compositional structure revolve around the experiences and feelings of its main protagonist, the reclusive forester Jūlijs (July), who is envious of his friend Augusts (August), a mulled-wine merchant traveling to distant countries.

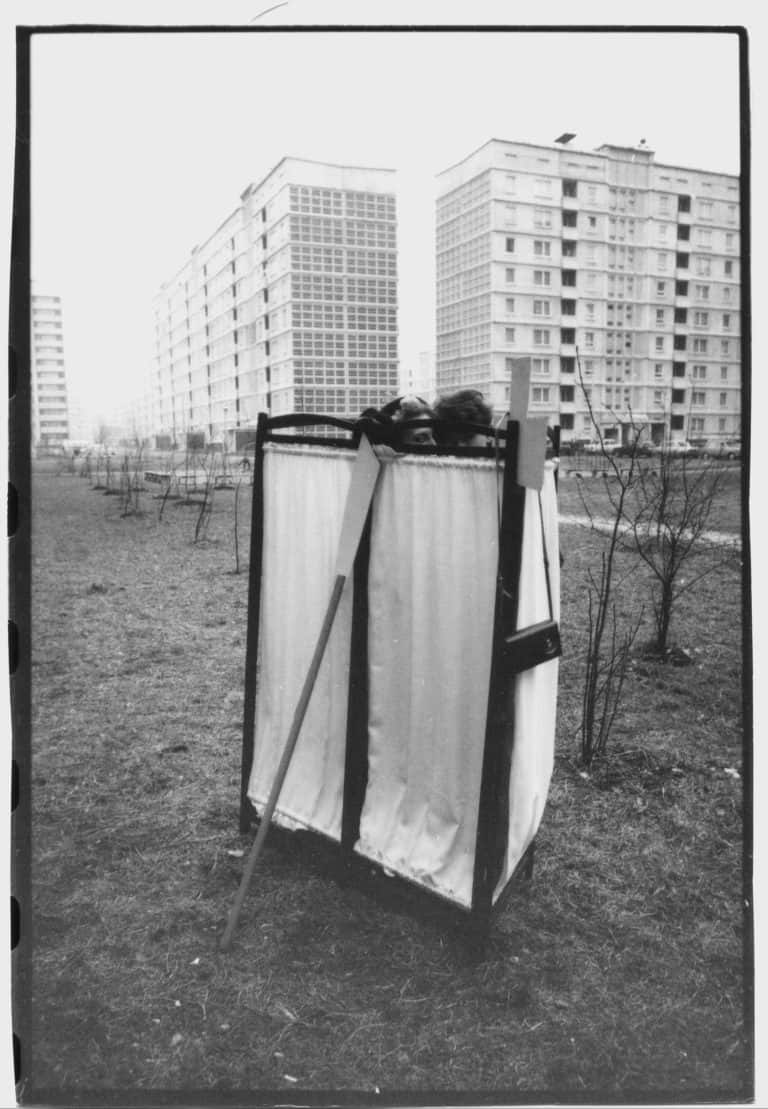

Members of NSRD explored postmodernist ideas in proposals presented in exhibitions of experimental projects of young architects as well as in the artists’ first solo exhibition The Wind in the Willows (Vējš vītolos).15This exhibition was organized by Hardijs Lediņš and Imants Žodžiks, and featured birch-tree patterned paintings by Leonards Laganovskis and the music recording “The Wind in the Willows” by NSRD. Held at the House of Architects in 1986, The Wind in the Willows featured staged settings of a living environment synthesizing colorful, asymmetrical, expressive objects (table, dressing screen, tableware) inspired by designs by Memphis Milano and Studio Alchimia and motifs of nature—marsh reeds and wallpaper painted in a pattern of birch trees. Poetic exhibition text invited viewers to disperse the “clouds of rationalism” and “clouds of stereotypes” with the help of diverse kinds of wind—“south-green wind,” “wind of the willows,” and “the wind of your eyelashes.”16Hardijs Lediņš and Imants Žodžiks, texts for the exhibition The Wind in the Willows, Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga. The display incorporated a recording of NSRD reproducing the howling sounds of wind. A similar aim to introduce qualities of subjective expressivity, individualism, and intimacy, this time as a tool of critique of standardized designs, informed the artists’ first video-action Man in a Living Environment (Cilvēks dzīvojamā vidē), which Lediņš and Žodžiks produced in 1986. Analyzing the architectural shortcomings of prefabricated mass housing in Riga, video footage features a small group of performers traveling through neighborhoods of newly built block-house dwellings, interviewing inhabitants of these suburban districts, and staging delicate performative interventions introducing spontaneity and intimacy into the monotonous, standardized surroundings of the newly constructed city outskirts. In the video, analytical text on modern urban developments, read by Lediņš, is intermixed with the eclectic soundtrack of Latvian choir music, compositions of Laurie Anderson, and music by NSRD.

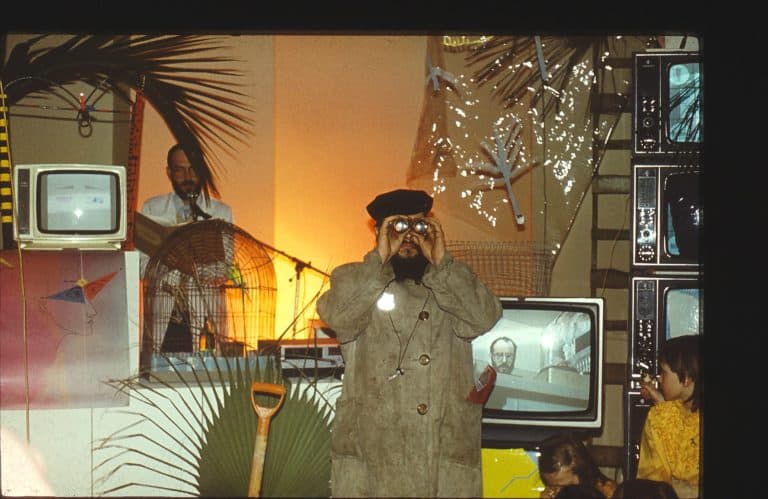

Following the success of The Wind in the Willows, NSRD members began to position themselves as an art collective, expanding their network of participants in the group’s performances, video-performances, and exhibitions, and revising their theoretical premises. Although still acknowledging expressive means of postmodernism, they became critical of superficial, formal applications of postmodern aesthetics. Instead, the group re-addressed themes present in their early writings, actions, and music albums—motifs that explore transient states of perception and the atmospheric ambience of particular locations. From 1986 onward, newly accessible video technology allowed them to combine the narrative, sonic, and visual elements of a time-based performance action. In a group statement, they explained, “For the Workshop, video is a means of expression necessary to encompass those sensations, for the restoration of which music, the written word, and actions are insufficient.”17“Nebijušu sajūtu restaurēšanas darbnīca” [Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings], manuscript in the Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga. This aspect of video led the group to use it in the creation of works that put into focus the interrelations of performance actions, often staged in rural, peripheral locations, with universal and cyclical processes in nature. In 1987, they recorded a number of semi-improvised, playful, or ritual-like performance actions unfolding before a backdrop of natural settings: Iceberg’s Longing / Volcano’s Dreams (Aisberga ilgas / Vulkāna sapņi, 1987), Grindstone of the Spring (Pavasara tecīla, 1987), Walk to Bolderāja (Gājiens uz Bolderāju, 1987), and Dr. Eneser’s Binocular Dance Lessons (Doktora Enesera binokulāro deju kursi, 1987).

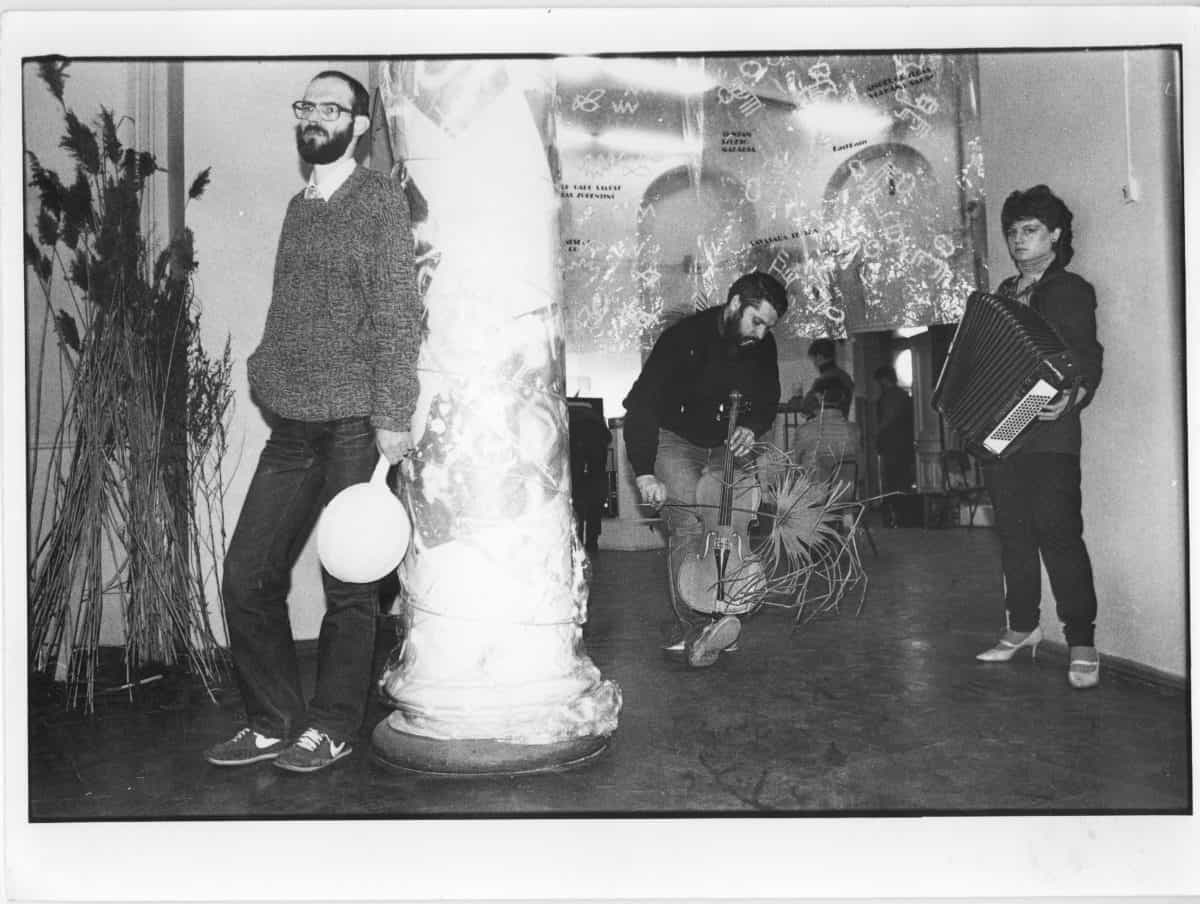

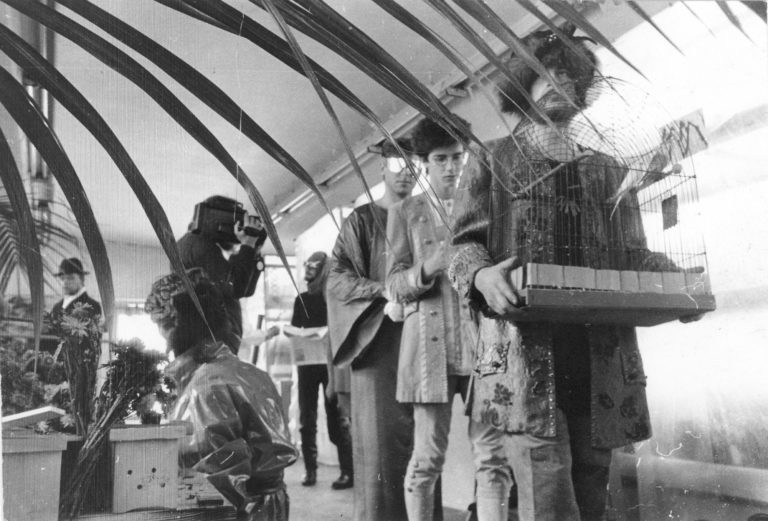

The group’s video-performances were informed by the newly coined original concept of Approximate Art developed by NSRD in 1987. The idea of “approximation” was seen as in opposition to the alleged precision of technological advancements and the systemic approach to indeterminacy of human experience and accentuated ambient, borderline states of perception. It substantiated the group’s transmedial practice by highlighting the disappearing boundaries between art genres and forms, and arguing for individual, subjective understanding of a polysemic artistic action. As Lediņš explains in one of the texts on Approximate Art: “Since practically all natural phenomena and processes are perceived by the brain as approximate things, it can be argued that approximation is one of man’s most human characteristics. . . . Applying the notion of approximation to art, we arrive at a phenomenon that is very characteristic of today’s world and that the critics find impossible to resolve. The boundaries between different art genres are very blurred, they cannot be defined, just like the boundaries between different cultures. The question often arises—is it art or is it already not art?”18Hardijs Lediņš, “Auf dem Weg zu Ungefähren” [On the Way to the Approximate], in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde, 71–73, 72; reprinted and translated into English in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 220–21. Liberalization during the perestroika period, which began in 1985, made it possible for NSRD to access public exhibition and concert venues. The concept of Approximate Art served as a basis for the group’s first exhibition realized in the visual art context—The First Exhibition of Approximate Art,held in the House of Knowledge in Riga in spring 1987. The six-day event featured a designed environment, a multichannel display of video-performances by NSRD and other artists, and daily performances and musical interventions by NSRD as well as by invited musicians and artists.

In the years that followed, the group revised their concept of Approximate Art, as is reflected in the Second Approximate Art Exhibition: Mole in the Hole, which was held in Riga in 1988, and in the display that the group prepared for the exhibition Riga. Lettische Avantgarde (Riga: Latvian Avant-garde), which took place in West Berlin, Bremen, and Kiel in 1988–89. NSRD ceased collaboration in 1989. The oft-cited reasons for the breakup of the group are the sociopolitical and economic changes that affected society during the years of dissolution of the Soviet Union and that led members to seek their own, individual creative paths. Yet it could be argued that NSRD’s encounter with the framework of professional art institutions through their participation in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde also contributed to this process—the time-based, multimedia artistic practice of the collective and the idiosyncratic concept of Approximate Art proved to be difficult to adapt to the institutional, white-cube context—and to international art circulation. Still, since the rediscovery of the full scope of the group’s transmedial, collaborative artistic legacy in the mid-2000s, their work and ideas continue to inspire younger generation of Latvian artists and musicians, who on their own initiative, have engaged in reenactments of the Walks to Bolderāja, reconsidered the storyline of the novel Zun, and continue to reinterpret the performances and architectural proposals of the members of NSRD.

The author would like to thank the Latvian Centre for Contemporary art for their cooperation during the preparation of this essay.

- 1Piotr Piotrowski, “On the Spatial Turn, or Horizontal Art History,” Umeni / Art 56, no. 5 (2008): 378–83.

- 2Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, “Provincializing Paris. The Center-Periphery Narrative of Modern Art in Light of Quantitative and Transnational Approaches,” in “Spatial (Digital) Art History,” special issue, Artl@s Bulletin 4, no. 1 (2015): 61.

- 3Tomasz Grusiecki, “Uprooting Origins: Polish-Lithuanian Art and the Challenge of Pluralism,” in Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present, ed. Beáta Hock and Anu Allas (London and New York: Routledge, 2018), 25–38.

- 4See Claire Bishop, “Zones of Indistinguishability: Collective Actions Group and Participatory Art,” e-flux Journal, no. 29 (November 2011), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/29/68116/zones-of-indistinguishability-collective-actions-group-and-participatory-art/. See also Andrei Monastyrsky, ed., Poezdki za gorod: Kollektivnye deistvia [Trips out of Town. Collective Actions] (Moscow: Ad Marginem, 1998), 19–24.

- 5See Mari Laanemets, Zwischen westlicher Moderne und sowjetischer Avantgarde: Inoffizielle Kunst in Estland, 1969–1978 (Berlin: Gebruder Mann Verlag, 2011), 123–24. Author’s translation unless otherwise indicated.

- 6Hardijs Lediņš and Juris Boiko, “Aptuvenās mākslas manifests” [Manifesto of Approximate Art, 1987], “Sarunas ar Mikiju Rēmanu. Pirmā” [Conversations with Micky Remann: The First, 1987], and “Sarunas ar Mikiju Rēmanu. Otrā” [Conversations with Micky Remann. The Second, 1987]. These manuscripts are held in the Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga. They are reprinted and translated into English in Ieva Astahovska and Māra Žeikare, eds., Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings: Juris Boiko and Hardijs Lediņš (Riga: Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2016), 222–27. Hardijs Lediņš, “Auf dem Weg zu Ungefähren” [On the Way to the Approximate], in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde, exh. cat. (Berlin: Elefanten Press, 1988), 71–73; reprinted and translated into English in ibid. 220–21.

- 7Occasionally, the core group was joined by artist Leonards Laganovskis (born 1955), musicians Mārtiņš Rutkis (born 1957), Nils Īle (born 1968), and Roberts Gobziņš (born 1964), and performer Dace Šēnberga (born 1967), among others.

- 8Hardijs Lediņš, “HL:NL,” interview by Normunds Lācis, Avots, no. 4. (1988): 52; reprinted and translated into English in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 139–48, 142.

- 9See Daiga Mazvērsīte and Māra Traumane, “Avant-garde Trends in Latvian Music, 1970s–1990s / Avantgardistische Strömungen in der Lettischen Musik von 1970–1990,” in Sound Exchange: Experimental Music Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe / Experimentelle Musikkulturen in Mitteleuropa,ed. Carsten Seiffarth, Carsten Stabenow, and Golo Föllmer (Saarbrücken: Pfau Verlag 2012), 239–44, 253–58, http://www.soundexchange.eu/#latvia_en?id=43. NSRD recordings are accessible on the Pietura nebijušām sajūtām website, www.pietura.lv.

- 10Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak, introduction to Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-based Art in Late Socialist Europe, ed. Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak (New York and Oxon: Routledge 2018), 1–16.

- 11Eckhart Gillen, “Ungefähre Kunst in Riga. Gespräch zwischen der Werkstatt zur Restauration nie verspürter Empfindungen und Eckhart Gillen” [Approximate Art in Riga: Conversation between “Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings” and Eckhart Gillen], Niemandsland. Zeitschrift zwischen den Kulturen 5 (1988): 33; reprinted and translated into English in abridged form in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 260.

- 12Lediņš and Boiko, “Manifesto of Approximate Art” (1987); reprinted and translated into English in ibid., 227.

- 13The original text is preserved in sixteen typewritten notebooks now held in the Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga.

- 14Hardijs Lediņš, “Zeitgeist und geistige Toposphäre / Laika gars un vietas atmosfēra” [The Spirit of Time and Atmosphere of Place], in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde 30, 79; reprinted and translated into English in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 439–40.

- 15This exhibition was organized by Hardijs Lediņš and Imants Žodžiks, and featured birch-tree patterned paintings by Leonards Laganovskis and the music recording “The Wind in the Willows” by NSRD.

- 16Hardijs Lediņš and Imants Žodžiks, texts for the exhibition The Wind in the Willows, Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga.

- 17“Nebijušu sajūtu restaurēšanas darbnīca” [Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings], manuscript in the Hardijs Lediņš archive, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga.

- 18Hardijs Lediņš, “Auf dem Weg zu Ungefähren” [On the Way to the Approximate], in Riga. Lettische Avantgarde, 71–73, 72; reprinted and translated into English in Astahovska and Žeikare, Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings, 220–21.