This essay focuses on Safia Farhat (Tunisian, 1924–2004), professor of decorative arts and sole woman artist in the École de Tunis, a group of Tunisian, French, and Italian painters who increasingly turned to craft-based mediums in their explorations of material and heritage.

As the entrepreneurial co-founder of the Société Zin, a modernist design company, Farhat contributed to the visual aesthetics of civic spaces during the formative period of Tunisian socialism and state feminism. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the artist created numerous murals and decorative programs to enhance the architectural environment of newly built schools, hotels, factories, banks, and government buildings. This essay introduces Farhat’s key role in sustaining a mural tradition among Tunisian modernists, and describes a selection of the artist’s monumental designs in which her characteristic hybrid creatures predominate. Crafted in ceramic tiles, paint, stone, iron, and wool, Farhat’s artistic corpus portrays animated scenes of laborers and artisans, geometric patterns associated with textiles and pottery made by women, nude female bathers, coastal motifs, and elements of industry. Hybrid organisms composed of flowers, birds, and artisanal symbols populate these fantastical environments. Many of the monumental works remain in situ across Tunisian civic spaces, serving as muted backdrops for the activities of students, teachers, tourists, laborers, and bureaucrats. What subdued histories might Farhat’s composite creatures, made up of anthropomorphized artisanal motifs associated with femininity, reveal?

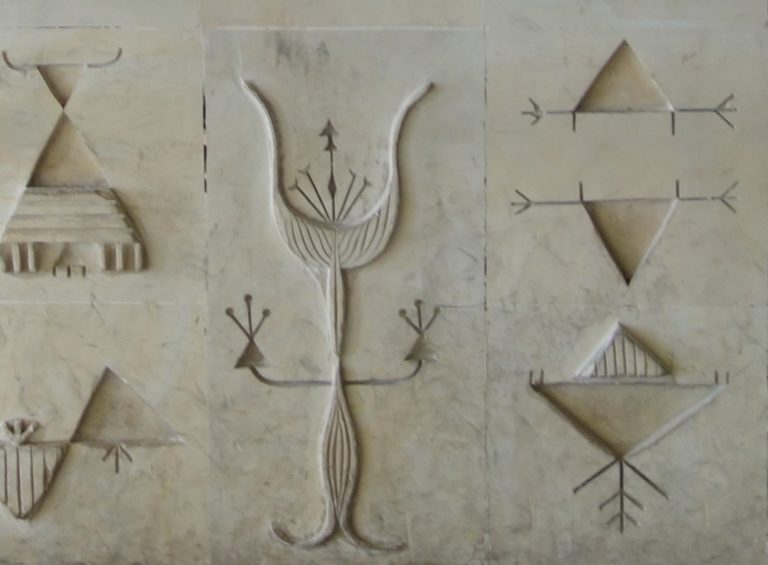

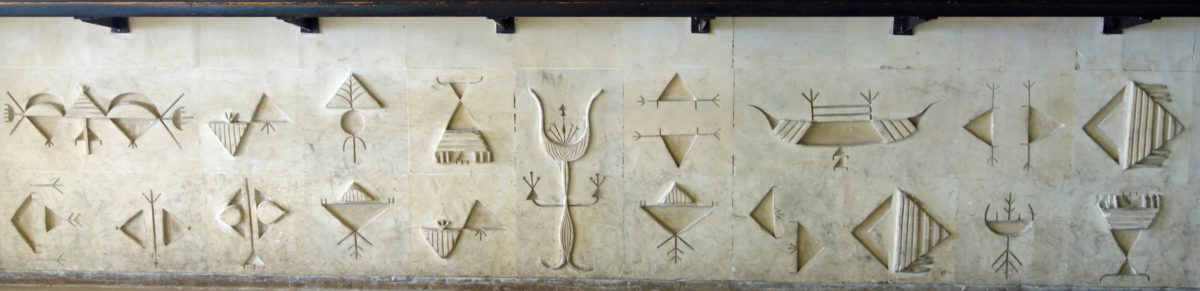

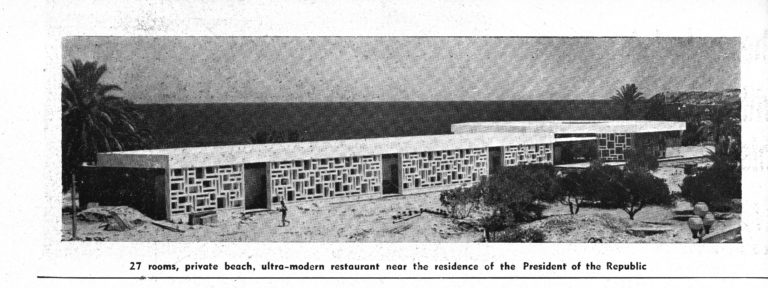

A nude woman bather floats along a current of stylized motifs, forming the focal point of a ceramic tile wall designed by artist Safia Farhat circa 1963. Decorating the reception area of the Hôtel Skanès Palace, located on the waterfront of the coastal resort area of Monastir-Skanès, the bather turns her oval eye toward passing guests and employees. The curvature of her breast and fingers mirrors the undulations of waves (fig. 1). She emerges from an imaginary seascape of floating elements: the rooftops of mosques, zigzags from carpets, triangular fish, flowering plants, and jewel-like biomorphic shapes. Two inset panels depicting gazelles and mythical composite creatures rest against the backdrop of deep blue and coral tiles. A few kilometers away, along the same beachfront, Farhat composed similar designs for the stone panels that decorate the bar in the restaurant of the Hôtel les Palmiers. Situated in a hotel adjacent to the presidential palace in the city of Monastir, the bar’s counter features two rows of geometric and biomorphic designs (fig. 2). Farhat’s evolving iconography may be characterized by such fantastical motifs drawn from women’s textiles, tattoos, jewelry, and ceramic wares. These designs germinate and sprout in Farhat’s decorative programs in Monastir’s secondary school and civic assembly hall, as well as in other sites across Tunisia. The artist’s composite creatures and artisanal motifs animate her compositions and reveal the entwining of gender, labor, and art during the 1960s.1This essay stems from research conducted for my book Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019). I am grateful to Nancy Dantas, Nene Aïssatou Diallo, and Smooth Nzewi for the opportunity to share my documentation of Safia Farhat’s decorative programs with MoMA audiences. I also thank Aïcha Filali for her generosity and unwavering support of this research over the years.

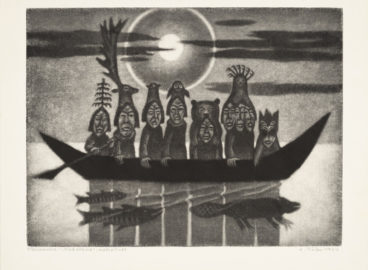

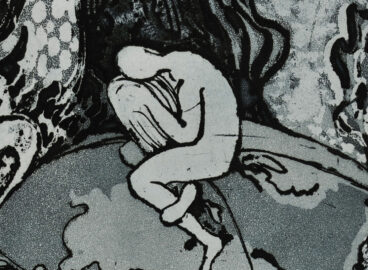

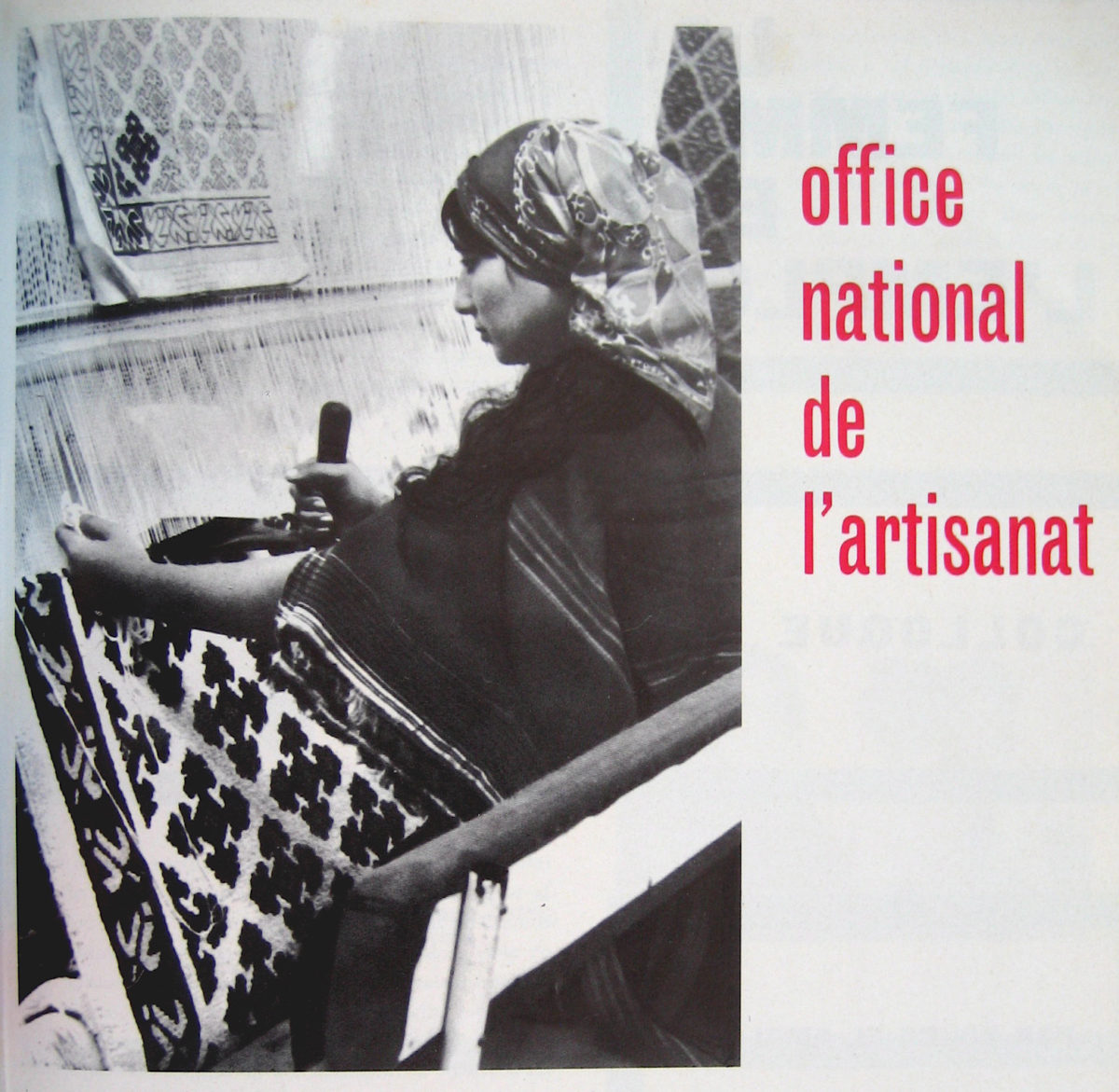

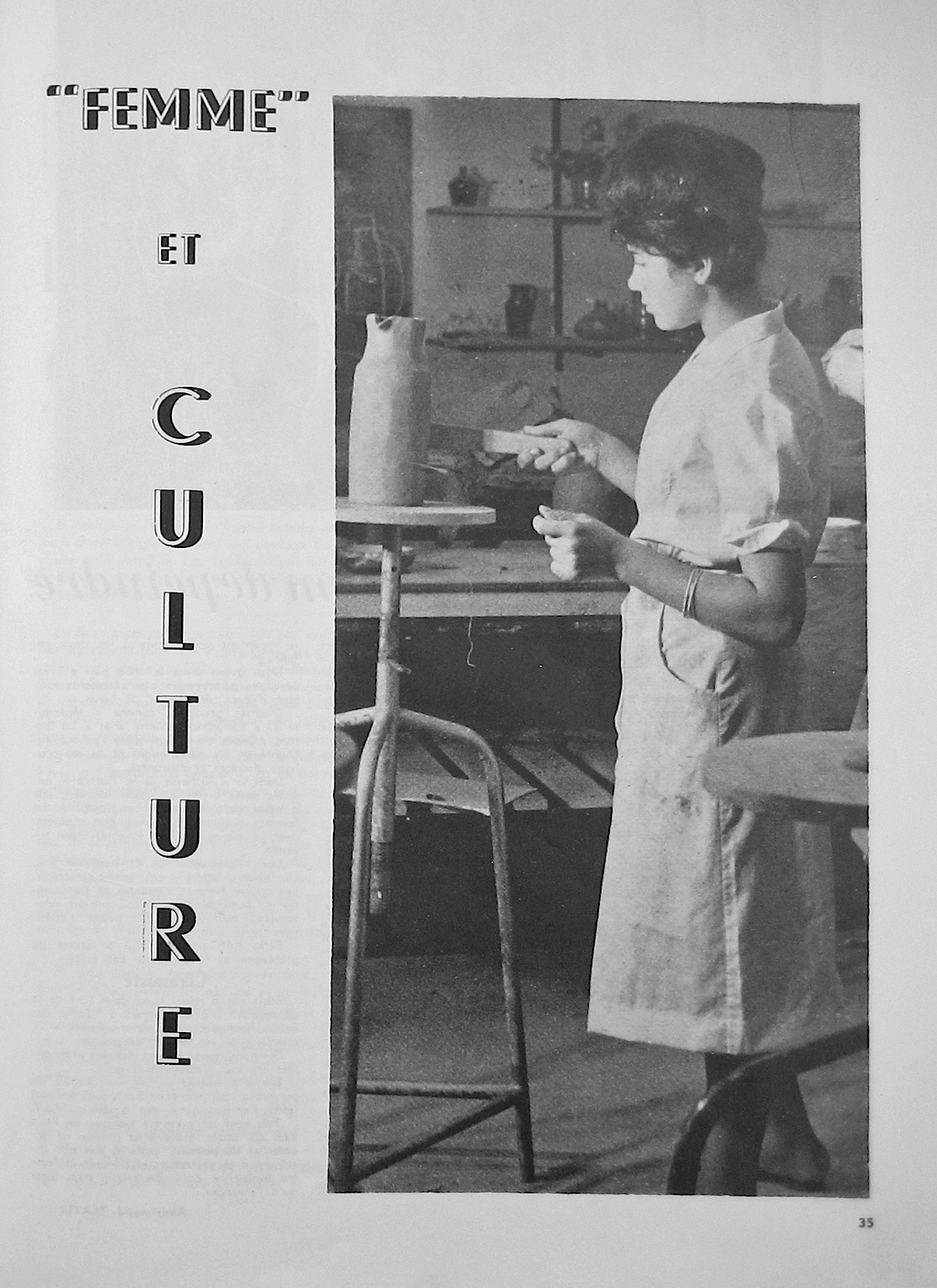

Safia Farhat worked across several professional domains as she sought to breathe new life into art forms associated with women’s artisanal production.2For a biography of the artist’s career and life, see Aïcha Filali, Safia Farhat: Une biographie (Tunis: MIM Éditions, 2005). The Safia Farhat Museum, which Filali opened in 2016, houses an important collection of the artist’s work. It is adjacent to Farhat’s former studio and art center in Radès. She created these decorative programs in the post-independence environment of the late 1950s and early 1960s, when family law reform in 1956 enacted a regime of state feminism, while broader initiatives aimed at women’s social and economic development endorsed the transformative power of creating art.3In the early postcolonial period, former president Habib Bourguiba initiated legislation and a vast program of socioeconomic reform intended to uplift the status of women in society; women’s legal rights, education, creativity, and economic potential were crucial components. State feminist discourses symbolically framed the weaver and her loom on a continuum of liberation and development. As a professor in and director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Tunis, Farhat negotiated the school’s contributions to state feminism and socialist reform, which together recast the arts historically produced by women. As larger numbers of women enrolled in secondary school and pursued higher education, in particular at the École des Beaux-Arts in Tunis, feminist narratives drew on the symbol of the woman artist to promote female creativity and independent thought, and to serve as a gauge for societal progress (figs. 3, 4).4For relevant writings, see the journal of the National Union of Tunisian Women, Femme, and the journal Faïza, a feminist publication founded by Safia Farhat in 1956. Moreover, the nationalist quest to establish a Tunisian modernist aesthetic gave momentum to the ennoblement of art forms subordinated as “handicraft” under the French protectorate. By the early 1960s, art forms such as weaving and ceramics came to represent possibilities for enhancing women’s social, economic, and intellectual autonomy.

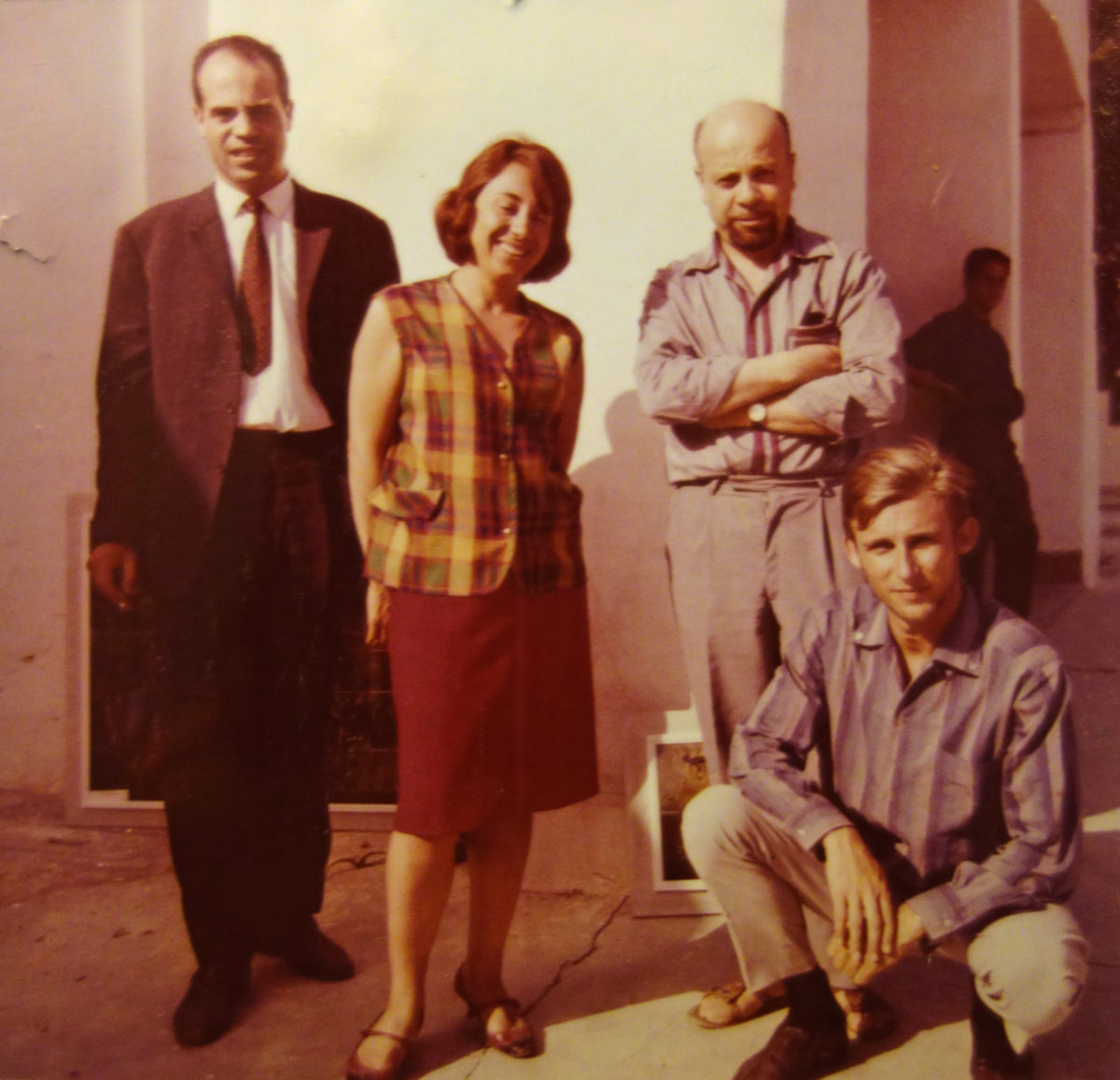

A professor of decorative arts at the École des Beaux-Arts, Farhat joined Abdelaziz Gorgi (Tunisian, 1928–2008) to become the school’s second Tunisian instructor in 1959; Gorgi taught ceramics from 1956 onward (fig. 5). Both artists were also members of the École de Tunis, a group of Tunisian, French, and Italian painters who increasingly turned to craft-based mediums in their explorations of material and heritage. As professors, Farhat and Gorgi shaped a beaux-arts curriculum that sought to elevate art forms categorized diminutively in colonial discourses as feminized craft. They sought to instill in a new generation of Tunisian students creative, entrepreneurial approaches to the modernist reinvention of art forms connected to local patrimony, as well as the confidence to propose innovative designs executed using craft processes. Under Farhat’s leadership, students in the atelier of decoration gained new perspectives on reviving “artistic craft” through field trips to artisanal centers. She also partnered with the National Office of Handicraft, and specifically weavers in the textile ateliers, to teach technique and design. A feminized bureau whose workforce was 80 percent female, the National Office of Handicraft attracted thousands of young, unmarried women into its pilot training programs because “handicraft,” especially weaving, represented an acceptable profession for lower-class women who, past primary-school age, sought opportunities for education and employment. Farhat’s experimental pedagogy endeavored to support collaborations between artists and artisans, and to cultivate female relationships across social classes.5See Gerschultz, Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École for a more in-depth analysis of class. As she undertook teaching and administrative responsibilities that integrated art and artisanal production, she simultaneously trained a new generation of women creators who would go on to bridge institutional divides.

In 1963, Farhat and Gorgi co-founded a design company, the Société Zin, that put their pedagogical approaches into praxis. This company took its name “Zin” from the Arabic word zīn, which denotes beauty, decoration, and the power to enthrall. Together, Farhat, Gorgi, and their collaborator Claude Béja designed and delegated orders for decorative programs that often overlapped with architectural commissions mandated by law. Specifically, the One Percent Law, reinstated in 1962 by presidential decree, required that a portion of every civic building’s budget be allocated to decoration.6The decree stipulated that the portion allotted to art should amount to no more than 1 percent of the total construction cost. Décret no. 62-295, August 27, 1962 (27 rabīʿ I 1382), in Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne (August 24–28, 1962): 1053. Fourteen years had passed since 1948, when École de Tunis artists Pierre Boucherle (French, born Tunisia. 1895–1988) and Yahia Turki (Tunisian, 1903–1969) first called for a One Percent initiative modeled after the French law in order to alleviate artists’ financial duress and to provide steady work. Their principal motivation—to offer tangible support to select professional artists—remained in the law’s postcolonial iteration. Undated letter from Boucherle and Turki to the resident-general, [1948], Archives Nationales de Tunisie. This law underscored president Habib Bourguiba’s emphasis on the arts as a product of societal and cultural advancement. It also enabled participating artists to capitalize on the so-called development decade as the government commissioned artworks for the building of dozens of centralized, state-run offices, the tourism and hotel industry, the redesign of Monastir (Bourguiba’s natal city), schools, and impermanent displays for trade fairs. New construction, concentrated in the capital and coastal regions, centered on tourist and bureaucratic infrastructures. Artists, frequently members of the École de Tunis and their artisan collaborators, were subcontracted to decorate civic buildings, producing more than a hundred murals, mosaics, obelisks, friezes, and tapestries in wood, ceramic, iron, glass, stone, and wool in the decade following the law’s reinstatement. A journalist with the newspaper La Presse elaborated the mission of the Société Zin: “Their goal, they tell us, is to attempt to renovate Tunisian decoration with a utilitarian intention in seeking to employ as many artisans as possible. We have an array of artist-artisans in Nabeul, Ksar Hellal, Kairouan, Hammamet, and elsewhere, such as ceramicists, stonecutters, nattiers [plant-fiber weavers], weavers.”“7Gorgi et Safia Farhat créent une société,” La Presse, May 10, 1963, 3. Author’s translation. Commissions for decorative programs not only created the conditions under which artistic collaborations across social classes could occur, but also brought visibility to these relationships.

Due to its strategic importance in the Ten-Year Plan, which underpinned Tunisian socialism and the Bourguibist struggle against underdevelopment, tourism was an early and vital source of artistic patronage.8The Ten-Year Plan of the 1960s was an economic framework intended to support Bourguiba’s comprehensive struggle against social and economic underdevelopment. Under this plan, the artisanal and textile industries became key parts of modernizing women’s work and societal attitudes toward gender. The Tunisian Tourist Hotels Company (Société des Hôtels Tunisiens Touristiques, or SHTT) was a public corporation established in 1959 to build a tourist infrastructure. The Société Zin facilitated many decorative projects for SHTT hotels by providing clients with architectural plans and proposing designs for decorative programs. Depending on a project’s size, scale, and medium, Farhat and Gorgi hired collaborating artisans for its execution and employed iconographic references to dramatize the budding artisanat artistique (artistic craft industry). Hotels also purchased handmade objects such as rugs, ceramic vases and ashtrays, and wrought iron candelabras to complete the decor. The tourism industry promoted the concept of uplifting the artisan, stating in its bulletin, “In Tunisia as elsewhere, the craftsman must learn new skills to become both an able technician and creative artist. The 20th Century has assigned him a new and appropriate role: that of enriching daily life by beautifying useful and functional objects.”9“Made in Tunisia,” Tourism in Tunisia 3 (April 1960): 3.

The blend of fantastical, animate elements and symbols of feminine labor, which characterizes Farhat’s ceramic tile wall in the Hôtel Skanès Palace, in fact threads her decorative commissions of the period. In partnership with Gorgi, Farhat designed the reception area of the Hôtel l’Oasis in Gabès and the restaurant-bar of the Hôtel les Palmiers in Monastir to be self-referential. Both seafront hotels feature ceramic tile murals, pierced ceramic walls, and sculpted stone decor that whimsically echo their particular decorative characteristics. Farhat’s stonework in the Hôtel l’Oasis, though now partially dismantled, includes fragments of geometric and vegetal motifs abstracted from women’s textile designs and tattoos. In one panel painted by an unknown renovator, a tattooed peasant woman holding a pomegranate wades through knee-deep water (fig. 6). Schools of fish bearing delicate geometric and floral patterns dart around her ankles; these oval creatures resemble the opaline shapes drifting through the bather’s seascape in the Hôtel Skanès Palace. Above, the fronds of a palm tree turn into resplendent jewelry-like patterns, accentuating the triangular fibula pinning the woman’s dress; similar fibulae spring to life in other compositions.

Other examples of hybrid artisanal creatures are visible in Farhat’s bar in the Hôtel les Palmiers, built by presidential architect Olivier-Clément Cacoub for the hotel adjoining Bourguiba’s summer palace (fig. 7); her stonework depicts animate fibulae and geometric and biomorphic designs similar to those in Gabès and Monastir-Skanès. Highly stylized triangular fish and aquatic creatures (like phytoplankton) swim and float across the bar’s frontispiece. These auspicious symbols re-create the orderly structure of a woven grid. Linear motifs, like small propellers, protrude from the triangles; the “arms” and “hands” of the central anthropomorphic design suggest feminine patterns and a bridal motif found in weaving (fig. 8). In addition, Farhat and Gorgi decorated both hotels with pierced, undulating ceramic walls in vivid orange and in pale turquoise and green. In the Hôtel les Palmiers, Gorgi’s luminescent screen of gazelles, horses, and birds morphing into flowers separates Farhat’s bar from the dining-lounge area and encircles the restaurant (fig. 9). The installation of these artworks in new spaces of economic and ideological power situated them in development discourses, especially, as Tunisian scholar and artist Aïcha Filali (born 1956) has articulated, during a period when hotels officially served as “windows into the country.”10Filali, Safia Farhat, 106. While tourism constituted one significant source of patronage for Farhat, she also created monumental works featuring hybrid creatures for state offices and factories.

Farhat’s stone monument L’homme et le travail (Man and Work), which she designed in 1964 for the entrance to the National Institute of Productivity in Radès, amalgamates motifs that exemplify their collective inscription in the institutions of economic and gender reform (figs. 10, 11). Sculpted in low relief by stonecutters from Dar Chaabane, this triangular post displays images on three sides. The composition on the first side depicts a stylized male figure in profile sniffing a mashmūm (bouquet of jasmine buds), which he grasps with pointed fingers. On the second side, a sturdy plant, rooted firmly in the ground, sends up curling leaves and a flower bud, which cups a fish. One bird, which stands atop the flower, is personified with flowing hair and a large, oval-shaped eye. An arched doorway frames these hybrid creatures. On the third side of the post, archetypal plants grow in three-dimensional layers above a cogwheel, a symbol of Bourguibism. Farhat’s iconography elicits the sociocultural and agricultural programs of the National Institute of Productivity, the developmental aims of which she interrogated through her own collaborations with artisans and art students.

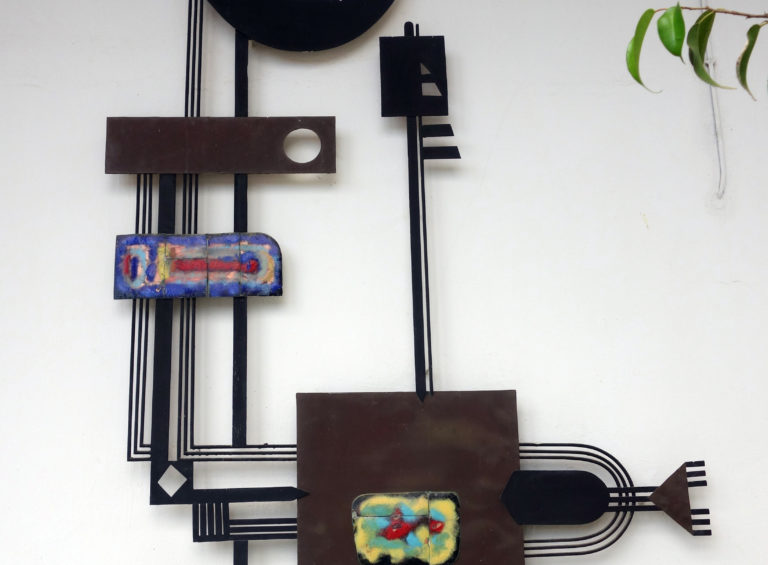

Farhat installed friezes in iron and enamel on the facade of the central office of the Tunisian Sugar Company in Béja that invite powerful comparison to her realist mural inside the main entrance (figs. 12–14). The abstract imagery of the exterior friezes consists of stacked lines, zigzags, half-moons, and geometric shapes evoking the core elements and colors of an unraveled tapestry. The dynamic shapes and lines bend, suspending animated crescents and triangles resembling Farhat’s hybrid birds and angular fish. In the building’s interior, the artist painted a socialist realist–style mural depicting male workers holding tools (fig. 15). While at first glance the metallic iron compositions bear scant formal resemblance to the realist portrayal of heroic masculine workers, the thematic content of the murals and the forms and materials of the friezes bespeak the gendering of labor. Artisans and laborers occupied the same discursive fields related to societal advancement. Farhat drew regularly from the symbols, motifs, and materials associated with women weavers in probing the alignment of artistic and economic revivals, and she employed the labor and ingenuity of women artisans in her work. Her triangles, bouquets, and zigzags suggest those found in other women’s artistry, particularly textiles woven in Kairouan and regions of the southern interior, which were targeted by the National Office of Handicraft in its reorganization. Moreover, in official discourses, the laborer (epitomized by the woman weaver) represented the citizen deemed in need of social uplift. In the case of the Tunisian Sugar Company, an ironworker executed Farhat’s designs in a collaborative process between artist and artisan. In evoking the feminized artisanat, Farhat conjured the class-based, gendered division of labor inherent in the production process of the decorative commissions.

Textile motifs comprise the content of Farhat’s largest ceramic frieze, a culminating example of a decorative program in which diverse artistic genres and industries converge. Around 1964 Farhat and Gorgi received a commission from SOGICOT (Société Générale des Industries Cotonnières de Tunisie, or General Company of Tunisian Cotton Industries). At SOGICOT’s main factory in Bir Kassaâ, they merged artisanal and coastal themes for an audience of bureaucrats, designers, and textile workers. Farhat designed a vast ceramic tile mural to wrap around the exterior facade of the building, while Gorgi created a monumental stone obelisk to be set within a courtyard fountain. Farhat’s winding panels portray a mythical world in which feminine motifs are suspended in a watery blue seascape populated by human and animal figures and composite creatures made from anthropomorphized artisanal designs. Across the right wall facing the entrance, these designs interlace female figures, male figures in a boat, fish, flowers, and horses (fig. 16). The left wall bears some of these whimsical elements floating alongside hybrid artisanal creatures; landscapes composed of geometric elements evoking patterns of five (khumsāt), weavings, silver fibulae, and candlesticks (shamʿdan); and men’s bodies composed of geometric-patterned rugs (figs. 17, 18). Composite creatures made of flowers, birds, and textile motifs, patterned into a vivid blue, purple, and red garden, decorate the main entrance (fig. 19).

Seen as a trailblazer in economic development, SOGICOT was a strong employer of wage-earning women in the 1960s and 1970s. Bourguibist discourses equated the burgeoning industrial textile industry with handicraft, and emphasized its capacity to cultivate an “uneducated” female workforce. As Sonia Maarouf wrote for Femme in 1965, “Yesterday, this woman, who was a custodian of a generation characterized by nomadism, managed to find stability, and today we see her contributing to the building of a new society based on social justice.”11Sonia Maarouf, “Femme dans l’industrie,” Femme 3 (1965): 27. Author’s translation. Sixty-eight women designers, including Beaux-Arts graduates and factory workers alike, were to gain autonomy and professional experience in convergent textile industries perceived as intimately connected to women’s hands and bodies. Farhat’s portrayals of feminine artisanal production, animated by her composite creatures, are discursively linked to embodied labor, constituting an insightful visual record of the interface between fine art and craft in their evocation and materialization of gendered hierarchies of production. These linkages, in turn, delineate the works’ inscription in the infrastructure of gender reform and economic growth, and in an aesthetic of self-referentiality characteristic of the artist’s work of the period.

- 1This essay stems from research conducted for my book Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019). I am grateful to Nancy Dantas, Nene Aïssatou Diallo, and Smooth Nzewi for the opportunity to share my documentation of Safia Farhat’s decorative programs with MoMA audiences. I also thank Aïcha Filali for her generosity and unwavering support of this research over the years.

- 2For a biography of the artist’s career and life, see Aïcha Filali, Safia Farhat: Une biographie (Tunis: MIM Éditions, 2005). The Safia Farhat Museum, which Filali opened in 2016, houses an important collection of the artist’s work. It is adjacent to Farhat’s former studio and art center in Radès.

- 3In the early postcolonial period, former president Habib Bourguiba initiated legislation and a vast program of socioeconomic reform intended to uplift the status of women in society; women’s legal rights, education, creativity, and economic potential were crucial components. State feminist discourses symbolically framed the weaver and her loom on a continuum of liberation and development. As a professor in and director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Tunis, Farhat negotiated the school’s contributions to state feminism and socialist reform, which together recast the arts historically produced by women.

- 4For relevant writings, see the journal of the National Union of Tunisian Women, Femme, and the journal Faïza, a feminist publication founded by Safia Farhat in 1956.

- 5See Gerschultz, Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École for a more in-depth analysis of class.

- 6The decree stipulated that the portion allotted to art should amount to no more than 1 percent of the total construction cost. Décret no. 62-295, August 27, 1962 (27 rabīʿ I 1382), in Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne (August 24–28, 1962): 1053. Fourteen years had passed since 1948, when École de Tunis artists Pierre Boucherle (French, born Tunisia. 1895–1988) and Yahia Turki (Tunisian, 1903–1969) first called for a One Percent initiative modeled after the French law in order to alleviate artists’ financial duress and to provide steady work. Their principal motivation—to offer tangible support to select professional artists—remained in the law’s postcolonial iteration. Undated letter from Boucherle and Turki to the resident-general, [1948], Archives Nationales de Tunisie.

- 7Gorgi et Safia Farhat créent une société,” La Presse, May 10, 1963, 3. Author’s translation.

- 8The Ten-Year Plan of the 1960s was an economic framework intended to support Bourguiba’s comprehensive struggle against social and economic underdevelopment. Under this plan, the artisanal and textile industries became key parts of modernizing women’s work and societal attitudes toward gender.

- 9“Made in Tunisia,” Tourism in Tunisia 3 (April 1960): 3.

- 10Filali, Safia Farhat, 106.

- 11Sonia Maarouf, “Femme dans l’industrie,” Femme 3 (1965): 27. Author’s translation.