In 1970, Johnson Donatus Aihumekeokhai Ojeikere, otherwise known as J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (Nigerian, 1930–2014), made Fro Fro, the point of departure of this short text. Storyteller and lens-based artist Jumoke Sanwo reads this image, produced during Nigeria’s nationalist drive and considers Ojeikere’s subjects and their unapologetic defiance.

In 1970, Johnson Donatus Aihumekeokhai Ojeikere, otherwise known as J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (Nigerian, 1930–2014), made Fro Fro. His earliest dated work in the collection, this image, along with Two in One Piko (1970) and Brush Eko Bridge (1973), were featured in the 2014 MoMA exhibition A World on Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio.1A World of Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio, held at MoMA from February 8 to November 2, 2014, examined “the ways in which photographers and other artists using photography have worked and experimented within their studios, from photography’s inception to the present.” It featured “both new acquisitions and works from the Museum’s collection that have not been on view in recent years.” See https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1392. These three works, all of which are now in MoMA’s collection, are consistent with Ojeikere’s compositional approach of using a diptych format to show his subjects both from behind and in profile.

In Fro Fro, the point of departure of this short text, the female subject’s identity is obscured—according to Ojeikere’s signature style. Like all of the images in his series on hairstyles, it was shot from slightly above, with the emphasis on the subject’s crown, conferring importance on her hairdo. Ojeikere insisted the images are not portraits, but rather “views that reveal the hairdo as object, its form, material and structure.”2André Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere: Photographs (Zurich: Scalo, 2000), 49. His focus is the hairdo’s sculptural qualities, providing the viewer with a sweeping view—much like what a hairdresser in a salon would see. The images appear as visual representations of what Zaza Hlalethwa describes as that “fleeting but prized moment when hair braiders stand behind a client with a mirror to show them the completed look from behind.”3Zaza Hlalethwa, “On hair that speaks: The messages in J.D Okhai Ojeikere’s ‘Hairstyle’ series,” arts24, August 20, 2020, https://www.news24.com/arts/culture/on-hair-that-speaks-the-messages-in-jd-okhai-ojeikeres-hairstyle-series-20200820 First they hold the mirror posteriorly, and then move it to either side, giving the client what is, in effect, a panoramic view of the hairstyle.

Shot predominantly with a Hasselblad or Mamiya camera, Ojeikere’s hairstyle series, which he began in 1968 in the city of Lagos and worked on until his passing in 2014, weaves an intricate labyrinth of stories reflecting modern yet nuanced sociocultural expressions of his female subjects—among them, friends, church members, wives of friends, and later on, anyone with a traditional hairstyle who was willing to be photographed.4Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, 49. He was inspired to shift his focus to documenting the cultural life in Nigeria through portraiture during a road trip with his friend Erhabor Emokpae in 1967,5Nigerian sculptor Erhabor Ogieva Emokpae (1934–1984) is best known for creating the emblem of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, otherwise known as FESTAC ’77—a replica of the sixteenth-century ivory portrait of the Queen Mother, Idia. when he turned to immortalizing fading customs such as the traditional hairstyles and elaborate head ties worn by women.

Ojeikere had relocated to Lagos in June 1963 from the city of Ìbàdàn, where in the thick of a hyperculture and nationalist drive instigated by cultural actors in the city shortly after Nigeria’s independence, he had sharpened his photographic skills. Amid the national modernist movement driving for indigenization in the late 1960s and 1970s, his defiant subjects went against the trend of wearing wigs, or straightening and/or perming their hair to European standards, choosing instead to adopt the more traditional styles predominant among women in the “hinterland” as a statement to make space for the local.

Ojeikere described hairstyling as a “collective endeavor, one that reveals the traditional skills of the women in that society, created by one person, worn by another, and photographed by a third person.”6Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, 42. In Fro, Fro (1970), the diptych format enables the viewer to see both the side and back of the sitter’s head and hairdo. Her hair is divided into six “lines,” a style colloquially referred to as òjò npetí (the rain cannot beat the ears), woven in the traditional dídì olówó, an ancient braiding technique that dates back to 500 BCE and can be seen on Ife bronze heads.

These idealized portraits show the intricately braided hairstyles worn for centuries by women from Ile-Ife—considered by the Yoruba to be the legendary cradle of humankind—and that spread across western Africa. As Titus A. Ogunwale has noted, from the Republic of Benin to Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal, the “regional differences in hairstyles are quite strong, sometimes permitting an observer to geographically identify a woman.”7Titus A. Ogunwale, “Traditional Hairdressing in Nigeria,” African Arts 5, no. 3 (Spring 1972): 44–45. In similar regard, in Igboland, the hair symbolizes the marital status of women, with the Ngala, the traditional bridal hairstyle, signifying the bride’s pride and elegance. In 1968, during the Nigerian civil war, hairdos became a symbol for women confronting the unrealistic expectation that they will marry. A new hairstyle named di gbakwa oku (marriage and husband can go to hell) emerged among the women in the region known as Biafra in what Christie Achebe describes as “direct response to an environment that demanded old ways of doing things, even as circumstances were rapidly changing.”8Christie Achebe, “Igbo Women in the Nigerian-Biafran War 1967–1970: An Interplay of Control,” Journal of Black Studies 40, no. 5 (May 2010): 803.

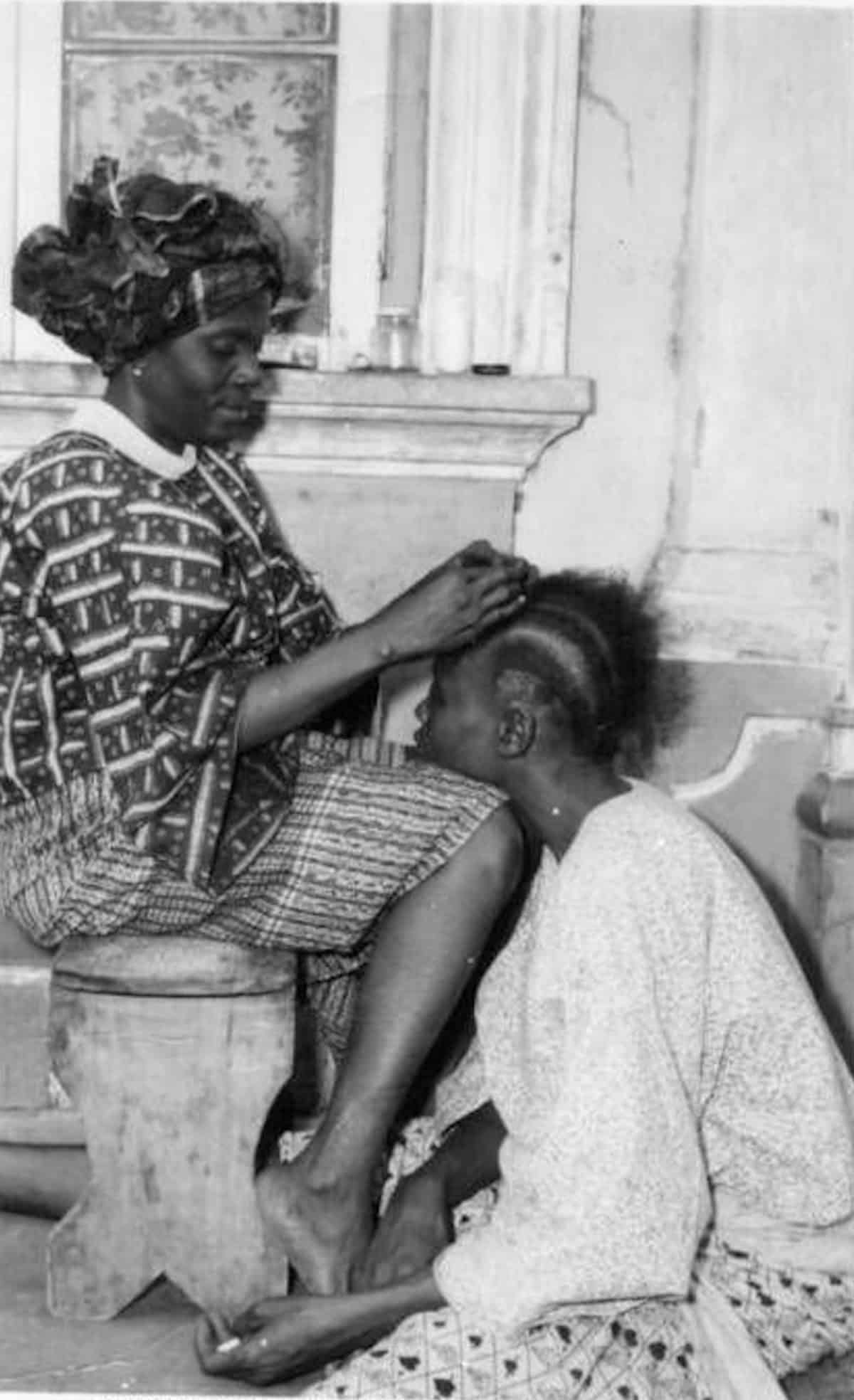

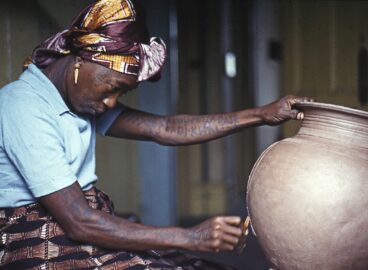

For centuries in societies across Africa, the practice of hairstyling has held sociocultural import as a marker of age group, social hierarchy, and the individuality and communal leanings of women. Women usually had their hair styled by friends or older relatives, and were sometimes paid to make intricate hairdos for others—in makeshift salons in private bedrooms, on verandas, and in courtyards. Hairstyles were made by women for women as a social activity, revealing the traditional skill sets of women. In Yorubaland, traditional hairstyles are, according to Marilyn Hammersley Houlberg, considered “the liveliest sculptural representation, communicating contemporary life.”9Marilyn Hammersley Houlberg, “Social Hair: Tradition and Change in Yoruba Hairstyles in Southwestern Nigeria,” in The Fabrics of Culture: The Anthropology of Clothing and Adornment, eds. Justine M. Cordwell and Ronald A. Schwarz (Berlin: De Gruyter Moulton, 1979), 349. The women sit on the floor, often on traditional eni mats, placing their chins on the knees of the hairdressers, who are seated on apotis, a special stool fashioned for domestic use. As the hairdresser plaits or weaves her subject’s hair in a traditional or sometimes contemporary hairstyle, they discuss personal and social matters.

The hairdresser uses her ojú inú (inner eye), which bestows the ability to divide the hair into sections, without recourse to tools, while exhibiting symmetry and balance to achieve a certain harmony and aesthetics. Beautifying hair is an obeisance to orÍ-inú (inner head), a practice of commemoration preceding spiritual festivals, and the celebration of deities such as Yemoja, Osun, Sango, etc. As Babatunde Lawal explains, “The Yoruba have created a wide range of hairstyles that not only reflects the primacy of the head but also communicates taste, status, occupation, and power, both temporal and spiritual.”10Babatunde Lawal, “Orilonise: The Hermeneutics of the Head and Hairstyles among Yoruba,” Tribal Arts 7, no. 2 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002): 3. Hair is regarded as a marker, differentiating humans from other species, and referred to as edá omo adáríhurun, which translates as “species with a full concentration of hair on their heads,” a term used to denote our species.

It is within this context that Ojeikere’s Fro Fro emerged, the first in what became a series of more than two thousand images chronicling the late photographer’s observation of Nigerian women’s hairstyles, which he described as serving a dualistic purpose of “ethnography and aesthetic” documentation.”11Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, 286. Fro Fro, Two in One Piko, and Brush Eko Bridge capture fleeting expressions, gestures, and style, documenting the three-way exchange between the hairstylist, her female clients, and Ojeikere, the photographer, for a later audience. These images in MoMA’s collection represent a sliver of how the artist viewed modernity and deployed photography to represent what being modern meant to the women he photographed.12Bisi Silva, ed., J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (Lagos: Centre for Contemporary Art, 2014), 12.

In reproducing the images contained in this text, the Museum obtained the permission of the rights holders, whenever possible. If the Museum could not locate the rights holders, notwithstanding good-faith efforts, it requests that any contact information concerning such rights holders be forwarded so that they may be contacted for future editions.

- 1A World of Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio, held at MoMA from February 8 to November 2, 2014, examined “the ways in which photographers and other artists using photography have worked and experimented within their studios, from photography’s inception to the present.” It featured “both new acquisitions and works from the Museum’s collection that have not been on view in recent years.” See https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1392.

- 2André Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere: Photographs (Zurich: Scalo, 2000), 49.

- 3Zaza Hlalethwa, “On hair that speaks: The messages in J.D Okhai Ojeikere’s ‘Hairstyle’ series,” arts24, August 20, 2020, https://www.news24.com/arts/culture/on-hair-that-speaks-the-messages-in-jd-okhai-ojeikeres-hairstyle-series-20200820

- 4Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, 49.

- 5Nigerian sculptor Erhabor Ogieva Emokpae (1934–1984) is best known for creating the emblem of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, otherwise known as FESTAC ’77—a replica of the sixteenth-century ivory portrait of the Queen Mother, Idia.

- 6Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, 42.

- 7Titus A. Ogunwale, “Traditional Hairdressing in Nigeria,” African Arts 5, no. 3 (Spring 1972): 44–45.

- 8Christie Achebe, “Igbo Women in the Nigerian-Biafran War 1967–1970: An Interplay of Control,” Journal of Black Studies 40, no. 5 (May 2010): 803.

- 9Marilyn Hammersley Houlberg, “Social Hair: Tradition and Change in Yoruba Hairstyles in Southwestern Nigeria,” in The Fabrics of Culture: The Anthropology of Clothing and Adornment, eds. Justine M. Cordwell and Ronald A. Schwarz (Berlin: De Gruyter Moulton, 1979), 349.

- 10Babatunde Lawal, “Orilonise: The Hermeneutics of the Head and Hairstyles among Yoruba,” Tribal Arts 7, no. 2 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002): 3.

- 11Magnin, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, 286.

- 12Bisi Silva, ed., J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (Lagos: Centre for Contemporary Art, 2014), 12.