Zenta Logina (1908–1983) was a Latvian artist at work during the Soviet occupation. Her paintings, reliefs, and sculptural objects developed in a singular manner, as she broke away from the accepted framework of visual arts codified by the regime and crossed into the realm of contemporary art as we define it today. She worked on her own terms, forging new ground through collaboration with her younger sister, Elīze Atāre (1915–1993), whose lifelong support not only sustained Logina but also enabled her to leave behind a cache of several thousand works, a full investigation of which is ongoing.

Descending Underground in Two Steps

Soviet rule was not a homogenous phenomenon.1The occupation of the Republic of Latvia by Soviet forces and the establishment of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, took place in 1940 and, with a short disruption during the Nazi occupation in 1941–44, continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, when the Republic of Latvia regained its independence. Political and economic markers, among other factors, outlined the territory that shifted with each new party secretary and five-year plan devised in Communist Party plenary sessions. Against this backdrop, Latvian artist Zenta Logina’s private life and artistic practice played out for more than forty years.2Zenta Logina’s artistic life took off during the interbellum years of the 1920s and 1930s, which were formative for her. She acquired academic training under established tutors at the Latvian Art Academy and was introduced to more contemporary ideas at the studio of Romans Suta (1896–1944) and through her association with his circle. For four years she also frequented the studio of Russian Impressionist painter Sergey Vinogradov (1869–1938), who had a private workshop in Riga. Her own career as artist was taking off, too. She began exhibiting her paintings in 1932, in the context of the association “Zaļā vārna” (The Green Crow), and received positive reviews in the press and from colleagues. In 1933 she married Bonifācijs Logins, who fully supported her artistic aspirations until he was arrested in the first years of the Soviet occupation. (Years later, Zenta discovered that he had died already in 1942). Apart from her ongoing engagement with fine arts, she entered the sphere of industrial design, either at the encouragement of her sister, Elīze Atāre, who was establishing herself as an industrial designer at that time, or in response to contemporary ideas promoting the interlacing of art and everyday life. See Ksenija Rudzīte, Zenta Logina. Kosmiskie loki. Glezniecība, meti gobelēniem, telpiskie objekti, exh. cat. Collection of Zenta Logina.

The first distinctive period in Logina’s life as an artist was under the totalitarian regime of Joseph Stalin in the 1940s and early 1950s, with the slight incursion of the Thaw under Nikita Khrushchev in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Zenta Logina was in her late thirties and forties during this time. In different circumstances, she might have been an artist in her prime, mature in her style and established in her career. And, as the examples of some of her peers demonstrate, one could establish oneself quite well in the new order. In Logina’s case, her bleak and mainly formal engagement with the Soviet art establishment signaled her reluctance to be complicit.3It was impossible to opt out. Moreover, the Soviet regime forced a specific production output that was systematized, and it demanded that artists comply or lose the right to produce anything at all. Also, back then, “social parasitism,” or unemployment, was a criminal offense. In 1945, she was admitted into the Artists’ Union of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, Section of Painters. One can only imagine what must have gone through her mind when she was commissioned to produce posters declaring “The Red Army gave us a new lease on life!” and “Only the Stalin Constitution gave you the right to vote!” In 1950, her “insufficient artistic activity led to a decline in artistic quality, which is currently inconsistent with the standard required of members of the Artists’ Union.”4Collection of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, folder “Zenta Logina.” Zenta Logina was demoted to a member candidate or, more technically, expelled. Falling out of this circuit meant that her access to certain resources, including materials, commissions, and exhibition opportunities, was cut.

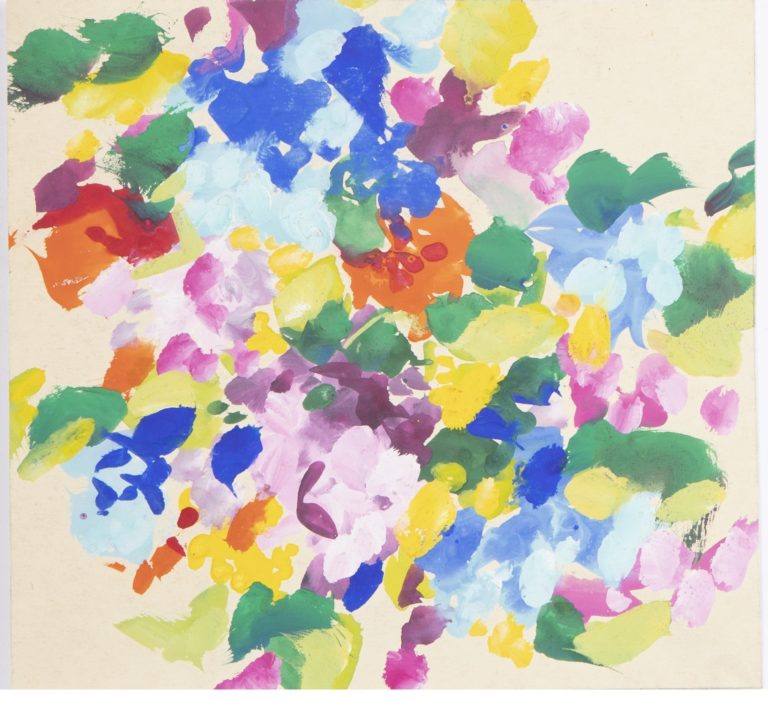

In the 1950s, after leaving the Artists’ Union, Zenta Logina moved in with her younger sister, Elīze Atāre, who had two rooms in what was a communal flat at 6 Blaumaņa Street in Riga. Elīze took on the household chores and, to support herself and her sister, worked as a graphic artist and industrial designer for several enterprises run by the Soviet socialist state. It was perhaps through this connection5In comparing where Elīze and Zenta worked in this period, one sees that they overlapped a great deal. See “4. Workplaces of Z. Logina,” manuscript owned by Pēteris Ērglis. that Zenta was granted a job in the textile industry. This opportunity, in turn, allowed her to regain full-fledged membership to the Artists’ Union in 1953—albeit, in the Section of Applied Arts, which required that she work exclusively as a textile artist.6Documentary sources indicate that in the 1950s, she participated in six exhibitions with factory-commissioned headscarf designs and fabric pattern samples. See Collection of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, folder “Zenta Logina.” And again, the lingering impression is that Zenta Logina approached this new role quite formally, that she complied with the rules but did not go out of her way to achieve more. Instead, her artistic energy was aimed at the easel waiting for her at home. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Zenta Logina never ceased to make art—that is, to paint in the manner she did before the occupation. Her main interest was at first in still life, especially flower compositions, but her canvases from this period show a gradual transition from the naturalistic forms of painterly language to a more generalized and abstract style. “It was as if she set a specific task for herself and then lost interest in the painting as soon as she had achieved it. She just piled up painting after painting, pushing each one aside to free up space for the next one,” is how Pēteris Ērglis, heir to her estate,7After Elīze Atāre died in 1993, all of Zenta’s works, the sisters’ collaborative works, and Elīze’s own works were kept in what had been their apartment at 6 Blaumaņa Street and cared for through the “Zenta Logina Fund,” which was established and run by Pēteris Ērglis, the son of a family friend. In 2012, after years of legal battles brought about by the denationalization of private property, the collection had to be relocated. remembers Elīze describing Zenta’s process.8Pēteris Ērglis, conversation with author, May 25, 2010.

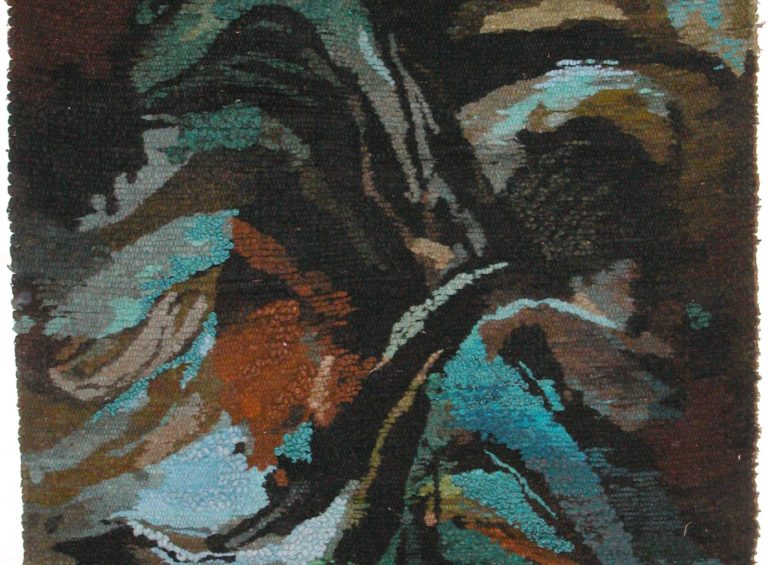

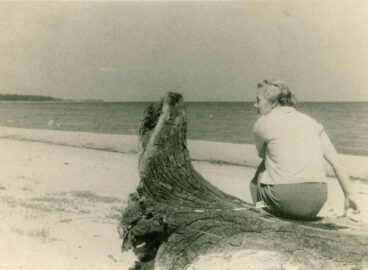

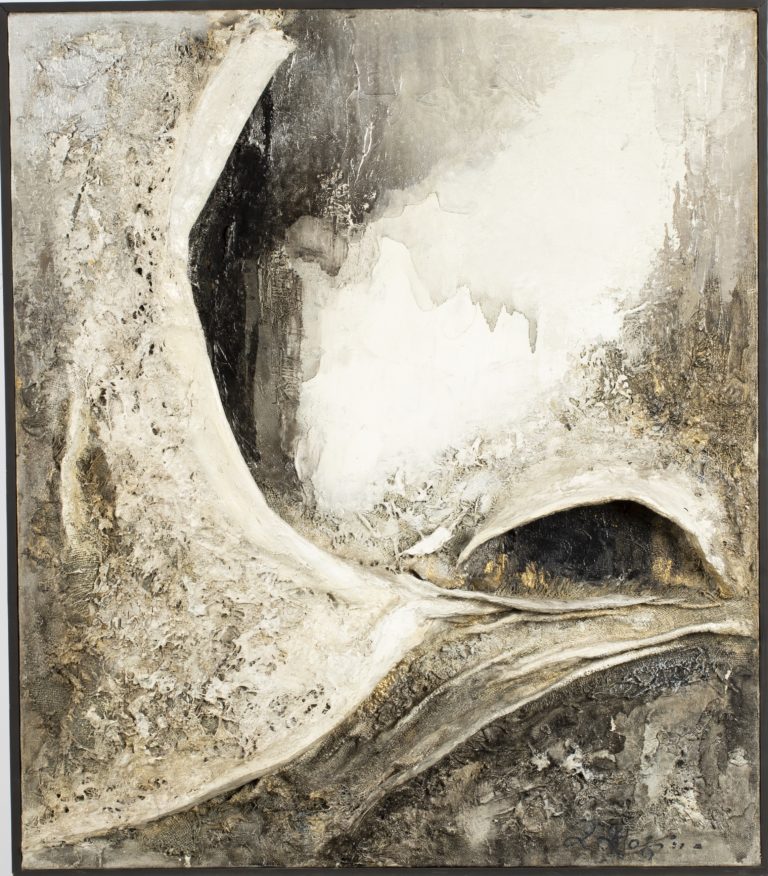

The second period in Zenta Logina’s artistic life came with her retirement in 1963 at the age of fifty-five and continued for the next twenty years. As of this point, she had time to pursue her art uninterrupted, and to direct her full attention to whatever subject she desired. Her interest in the genre of still life waned, and her subject matter diversified: in some cases, real-life elements such as a coffee table, a wooden log, or a chopper in the mountains can be discerned in her paintings from this period; in other cases, arrangements of color smudges or sharp lines don’t resemble anything in particular and bear the title “Composition”; and in still other cases, a poetic title reveals the idea behind the content of what is otherwise a rather abstract painting. Because of limited resources and the inaccessibility of needed materials, Logina’s paintings are not always oil on canvas—indeed, she used any available stain on any available surface. Gradually, she began breaking up the flat painted surface, adding different elements to it. By attaching wood, metal shavings, wire, string, and fibers with paint, varnish, glue, and epoxy resin, she created texture and added volume and expressiveness to the work and idea she wanted to embody and convey.

In the 1970s, the boundaries between the various types of art in which Zenta Logina engaged became even fuzzier. Paintings resembling reliefs led to three-dimensional objects and sculptures, and in the most radical cases, matured into full-blown spatial objects or installations. Newly devised shapes manifested the content in unique and sensuous ways. The subject matter of Logina’s output from this time is frequently astronomy, and specifically astrophysics, its concepts, data, and phenomena. For example, works such as Solar Wind, Meteorite, Black Hole, Cygnus Constellation, Alpha Centauri, and Formation of a Planet, among others, are exactly about that. Moreover, her juxtaposition of the macro-level Universe and the micro-level human experience suggests an exploration of more philosophical, cultural, and existential topics. Zenta Logina’s lifelong friend, astronomer Natālija Cimahoviča (1926–2019),9Logina led a rather insulated life, preferring the company of people from various fields of exact and natural sciences to that of artists and other cultural workers. Natālija Cimahoviča, who was among her circle of close-knit friends, was Head of the Department of Solar Physics at the Radio Astrophysics Observatory of the Academy of Sciences, and a member of the editorial board of the popular science journal Zvaigžņotā debess (Starry Sky). summarized this as follows:

“In Logina’s works, an adequate understanding of the composition of the Universe . . . was combined with an awareness of one’s cosmic self, of the part of man and the Earth in cosmic processes. In the colorful reliefs, galaxies glow and seemingly rotate, cosmic matter swirls, stars are born, and human thought vibrates. . . . Each person creates their own world. Artist Zenta Logina has given us a world of cosmic existence. There the enlightened soul of humanity is in constant dialogue with the darkness of people’s lack of reason, . . . rigidness of the formal logic—with the delicate twines of intuition, it’s a dialogue between the unchained spirit and the rules dictated by the physical form. Artist Logina’s world soars in the infinite space and time, it’s a view of the Earth from Space, the striving of man to rise over the strata of seemingly indispensable activities and unnecessary material things.”10Natālija Cimahoviča, “Kosmosa gleznotāja Zenta Logina,” Zvaigžņotā debess 1, no. 72 (1984): 60.

Works such as Weeping Planet, Burned-Out Planet, All Flesh Is Grass, Difficulties Shall Be Resolved, The River of Oblivion, The Shield of Justice, We Ourselves, and The Warning, among others, evoke the dark feeling of inevitability; they speak about the scale of human life and its fate in contrast to that of space and time, about the culture and its dependence on, interaction with, and responsibility toward the planet Earth and the Universe. Zenta Logina’s works confront the ecological disasters of the Soviet era as well as offer fertile ground for contemporary ecological discourse.

The Outside World

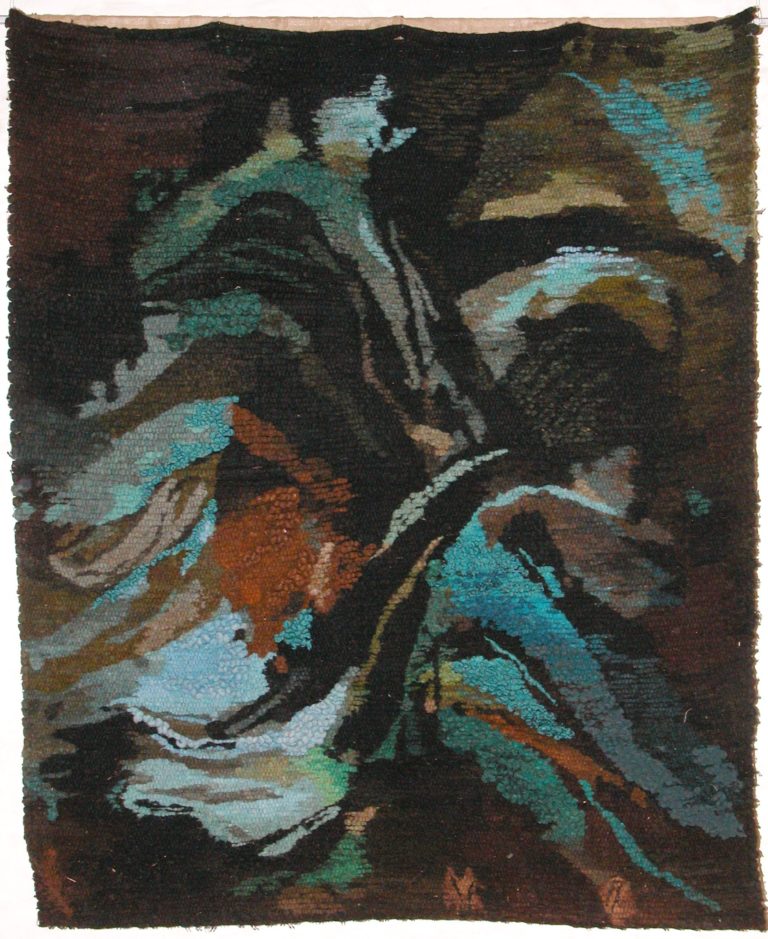

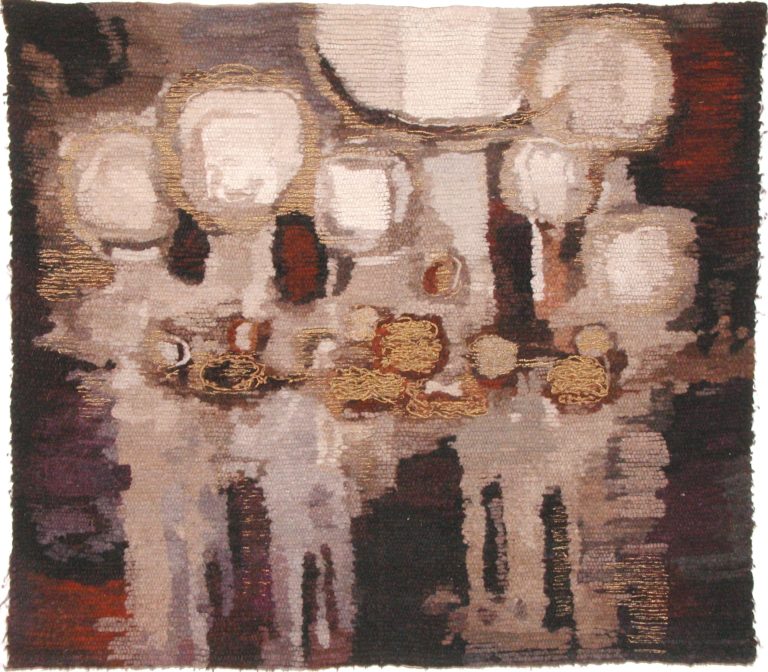

In the mid-1960s, the USSR underwent several institutional and organizational changes, the effects of which were felt well into the 1970s. In contrast to the fine arts, where “formalism” was targeted and censored for being too individualist and not promoting the ideals of the Soviet socialist ideology, the industrial arts, and by extension the applied arts, enjoyed more freedom of expression—if the goal was to provide Soviet citizens with useful and beautiful household objects, comfortable public spaces, and stimulating work environments. Consequently, the design sphere became an outlet for a variety of alternative artistic modes of expression. In 1963, the year Zenta retired, Elīze enrolled in a decorative arts workshop, where she learned to weave. It is impossible to tell whether she did so to secure an ongoing flow of resources, or as an act of sisterly love and support. However, her desire to show the world the art that she admired is clear—Elīze graduated in 1965 with a tapestry based on one of Zenta’s paintings. At this time, Elīze still worked as a designer. In fact, she was involved with several state-run industrial design enterprises until 1971, when she, too, retired. In the years that followed, in the relative seclusion of their two rooms, the sisters created their own alternative universe. To avoid unnecessary encounters with other inhabitants of their flat, they furnished their personal space with everything they needed to engage in their daily routine. They even brought in a stove to use for not only cooking but also dyeing yarns, which they did by hand. They tucked a loom between furniture, piles of books, stacks of completed artworks, and works still in progress.11One wall was left empty for the inspection of works in progress, which they reviewed through inverted opera glasses in order to create the necessary illusion of distance. Ērglis, conversation with the author, May 18, 2010.

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Elīze Atāre took up weaving based on Zenta Logina’s paintings as well as sketches, which the sisters designed together. They called these collaborative works “wall rugs” as they often were made in a way that deviated from the traditional tapestry-weaving techniques—Elīze used diverse methods, some of her own invention, and came up with a synthesizing, original approach. Over her lifetime, she wove sixty-five such wall rugs, ranging in size from small (approximately 35 1/2 x 27 1/2 inches) to huge (approximately 78 3/4 x 98 1/2 inches). The sisters’ previous affiliation with the applied art industry served as a gateway. Their tapestries were put on display in applied art exhibitions in Soviet Latvia and abroad, and quickly gained recognition. Numerous institutions and organizations bought them for their collections. However, people who saw these wall rugs woven by Elīze Atāre were not always aware of Zenta Logina’s contribution—let alone the artworks upon which they were based.

The first and only solo exhibition of Zenta Logina’s works of the Soviet period was organized by Elīze four years after Zenta’s death in 1987. The era of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (reconstruction) initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the second half of the 1980s launched a wave of events previously unimaginable. It included exhibitions of works of artists who, up until then, had never been acknowledged on such a scale. These exhibitions were often memorial, serving as tributes to the heritage of particular individuals rather than records of ongoing artistic efforts; nonetheless, in 1987, the public had a chance to explore the world of Zenta Logina in her own right, when a corner of the veil was lifted off her more abstract body of work.12The exhibition was held in Riga at St. Peter’s Church, a medieval building, which, following the dictates of scientific atheism, was converted into an exhibition hall for architectural propaganda. It frequently hosted exhibitions of applied art, including textiles, glass, and metal. Zenta Logina’s exhibition was visited by forty thousand people over the course of the three weeks it was open to the public. It received praise from fellow artists, physicists, and philosophers, as well as some negative criticism that linked her art with the technocratic nature of the Soviet rule.

Paradoxically enough, Zenta Logina’s art could have been interpreted favorably in the context of Soviet Union’s political and cultural program. It resonated well with the scientific aspirations and technocratic flare of the system—evoking space exploration, chemistry and nuclear physics, and cybernetics; it even brings to mind the peace movement and ecological concerns of the 1980s. However, the system had cast her as a treacherous element,13Zenta Logina was summoned and interrogated by the KGB on several occasions during her lifetime. and she had opted not to associate herself with it. Her focus on particular themes was, in fact, a form of dissociation from the Soviet social and political reality, a way of rising above it and finding a common ground in the universal. In the 1990s and 2000s, interest grew in the artists and cultural workers who had been neglected and suffered under Soviet rule. Zenta Logina was one such artist, and thus, an emblem for the correction of historical wrongs. However, the research into her artistic legacy on its own merits has only recently begun, and there is still much to be done. Unfortunately, there are no known sources enabling us to encounter Zenta Logina’s own voice. Her subjectivity is being constructed through the accounts of others, and by the interpretation of her artworks. As of today, her work is an integral part of the Zuzāns Collection, which to date, has acquired the largest holding.14Its collection of work by Zenta Logina and Elīze Atāre is still in the process of being properly catalogued, conserved, and restored, whereupon it can be made fully available for further research and public appreciation. There are other institutions and organizations in Latvia, Russia, and the United States15These collections include the Dodge Collection at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University; the Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow; the Latvian National Museum of Art; the Latvian Museum of Decorative Arts and Design; the Museum of the Artists’ Union of Latvia; the National Library of Latvia; the Information Center at the Art Academy of Latvia; the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art; and several private collections. Some of these institutions have online databases and have digitized Zenta Logina’s works. that house the sisters’ artworks, or significant bodies of information, and welcome researchers to examine it firsthand in order to further understand her practice.

- 1The occupation of the Republic of Latvia by Soviet forces and the establishment of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, took place in 1940 and, with a short disruption during the Nazi occupation in 1941–44, continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, when the Republic of Latvia regained its independence.

- 2Zenta Logina’s artistic life took off during the interbellum years of the 1920s and 1930s, which were formative for her. She acquired academic training under established tutors at the Latvian Art Academy and was introduced to more contemporary ideas at the studio of Romans Suta (1896–1944) and through her association with his circle. For four years she also frequented the studio of Russian Impressionist painter Sergey Vinogradov (1869–1938), who had a private workshop in Riga. Her own career as artist was taking off, too. She began exhibiting her paintings in 1932, in the context of the association “Zaļā vārna” (The Green Crow), and received positive reviews in the press and from colleagues. In 1933 she married Bonifācijs Logins, who fully supported her artistic aspirations until he was arrested in the first years of the Soviet occupation. (Years later, Zenta discovered that he had died already in 1942). Apart from her ongoing engagement with fine arts, she entered the sphere of industrial design, either at the encouragement of her sister, Elīze Atāre, who was establishing herself as an industrial designer at that time, or in response to contemporary ideas promoting the interlacing of art and everyday life. See Ksenija Rudzīte, Zenta Logina. Kosmiskie loki. Glezniecība, meti gobelēniem, telpiskie objekti, exh. cat. Collection of Zenta Logina.

- 3It was impossible to opt out. Moreover, the Soviet regime forced a specific production output that was systematized, and it demanded that artists comply or lose the right to produce anything at all. Also, back then, “social parasitism,” or unemployment, was a criminal offense.

- 4Collection of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, folder “Zenta Logina.”

- 5In comparing where Elīze and Zenta worked in this period, one sees that they overlapped a great deal. See “4. Workplaces of Z. Logina,” manuscript owned by Pēteris Ērglis.

- 6Documentary sources indicate that in the 1950s, she participated in six exhibitions with factory-commissioned headscarf designs and fabric pattern samples. See Collection of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, folder “Zenta Logina.”

- 7After Elīze Atāre died in 1993, all of Zenta’s works, the sisters’ collaborative works, and Elīze’s own works were kept in what had been their apartment at 6 Blaumaņa Street and cared for through the “Zenta Logina Fund,” which was established and run by Pēteris Ērglis, the son of a family friend. In 2012, after years of legal battles brought about by the denationalization of private property, the collection had to be relocated.

- 8Pēteris Ērglis, conversation with author, May 25, 2010.

- 9Logina led a rather insulated life, preferring the company of people from various fields of exact and natural sciences to that of artists and other cultural workers. Natālija Cimahoviča, who was among her circle of close-knit friends, was Head of the Department of Solar Physics at the Radio Astrophysics Observatory of the Academy of Sciences, and a member of the editorial board of the popular science journal Zvaigžņotā debess (Starry Sky).

- 10Natālija Cimahoviča, “Kosmosa gleznotāja Zenta Logina,” Zvaigžņotā debess 1, no. 72 (1984): 60.

- 11One wall was left empty for the inspection of works in progress, which they reviewed through inverted opera glasses in order to create the necessary illusion of distance. Ērglis, conversation with the author, May 18, 2010.

- 12The exhibition was held in Riga at St. Peter’s Church, a medieval building, which, following the dictates of scientific atheism, was converted into an exhibition hall for architectural propaganda. It frequently hosted exhibitions of applied art, including textiles, glass, and metal. Zenta Logina’s exhibition was visited by forty thousand people over the course of the three weeks it was open to the public. It received praise from fellow artists, physicists, and philosophers, as well as some negative criticism that linked her art with the technocratic nature of the Soviet rule.

- 13Zenta Logina was summoned and interrogated by the KGB on several occasions during her lifetime.

- 14Its collection of work by Zenta Logina and Elīze Atāre is still in the process of being properly catalogued, conserved, and restored, whereupon it can be made fully available for further research and public appreciation.

- 15These collections include the Dodge Collection at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University; the Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow; the Latvian National Museum of Art; the Latvian Museum of Decorative Arts and Design; the Museum of the Artists’ Union of Latvia; the National Library of Latvia; the Information Center at the Art Academy of Latvia; the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art; and several private collections. Some of these institutions have online databases and have digitized Zenta Logina’s works.