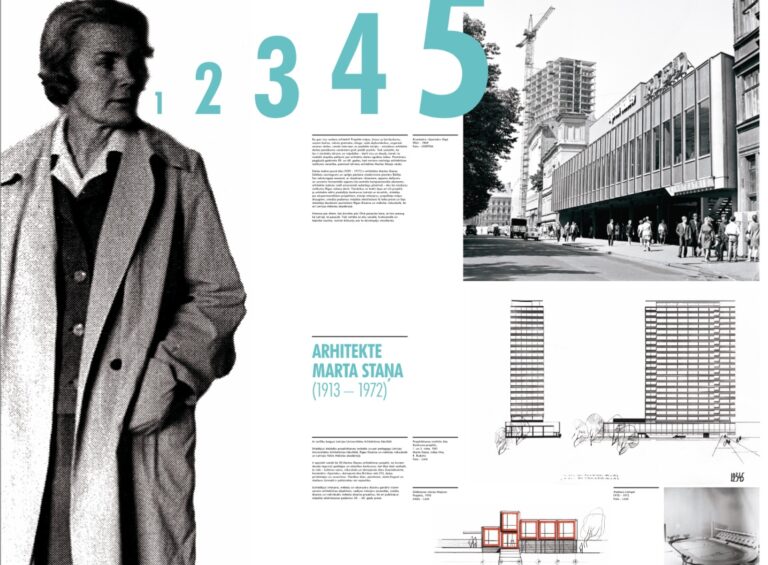

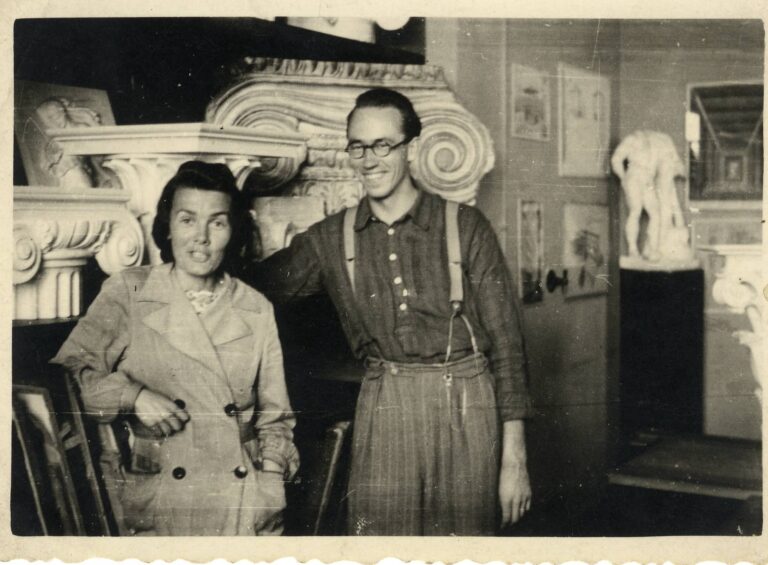

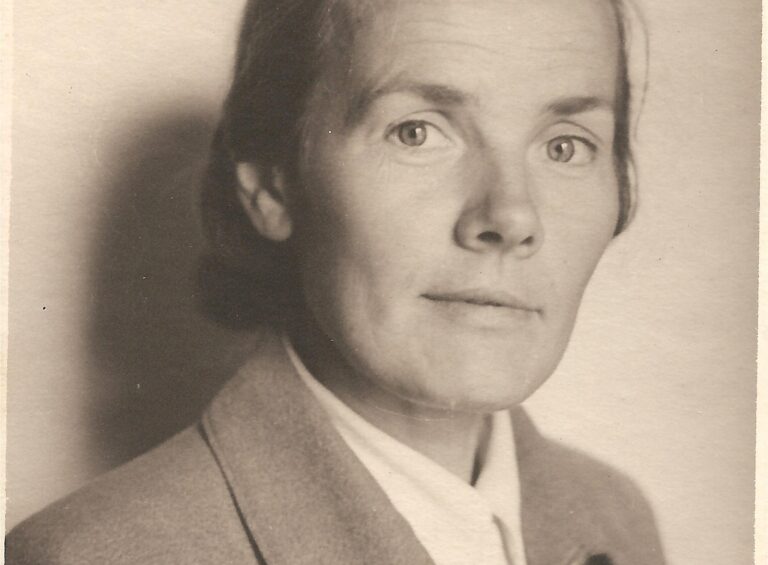

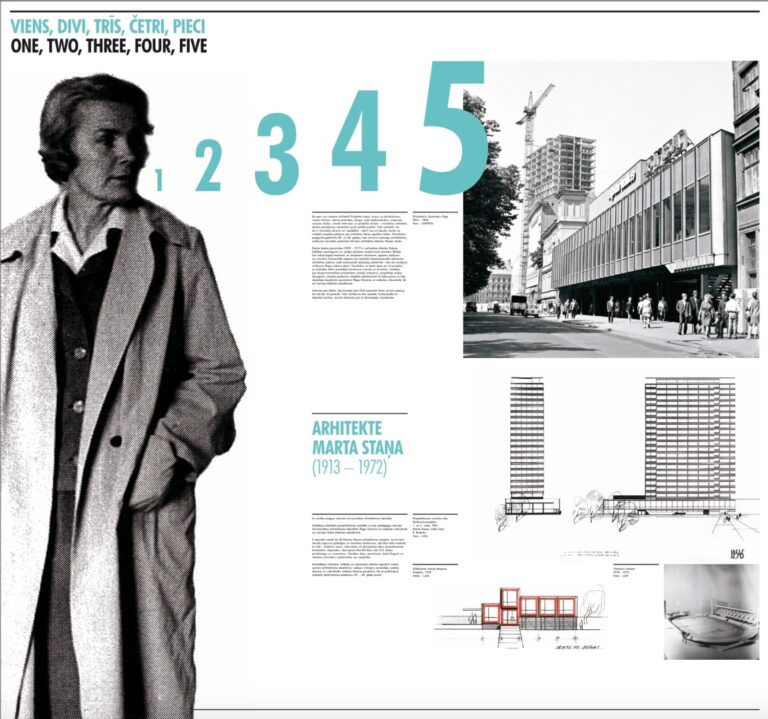

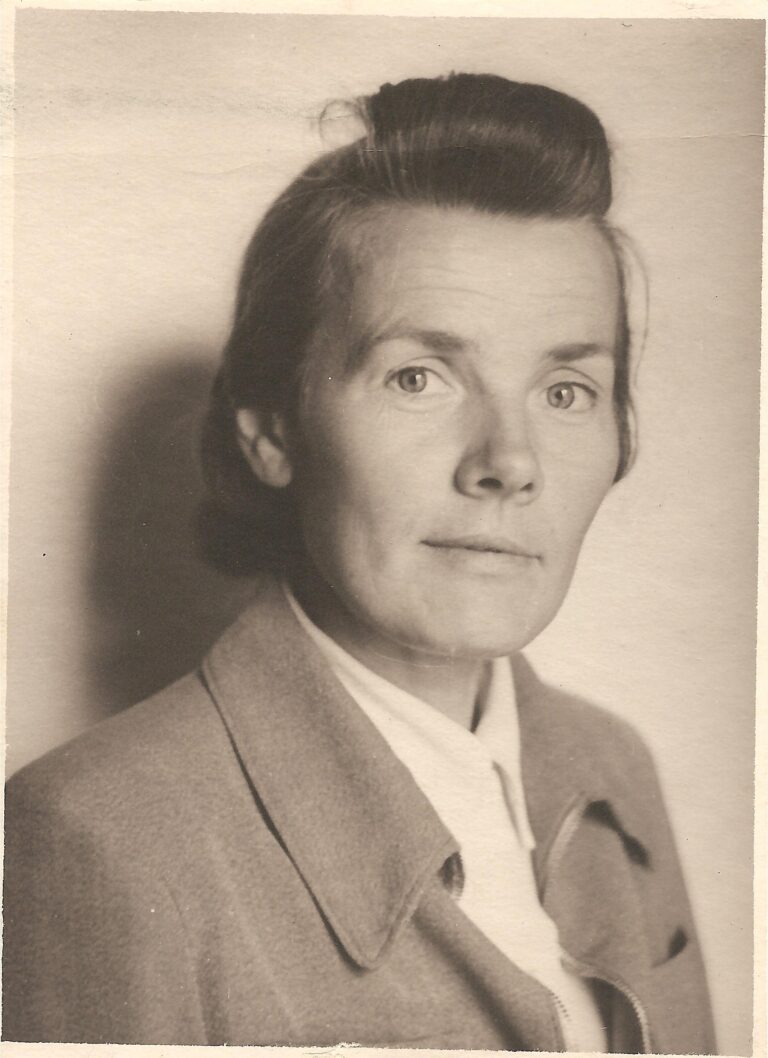

This essay examines the practice of architecture and the roles assigned to female architects in Latvia in the 1950s to the early 1990s through the life and work of Latvian architect Marta Staņa.

My initial encounter with Marta Staņa (1913–1972) and her work in architecture occurred in 2002 when, as a young architecture journalist, I had the opportunity to interview Latvian-Australian architect Andrejs (Andrew) Andersons (born 1942), who hailed from Riga. During our conversation, Andersons highlighted Staņa’s remarkable work, which, to my surprise, was not widely known in contemporary architecture circles at that time.

Further investigation revealed that Staņa was better recognized among artists and designers, many of whom had been her students at the Riga Art and Design School and the Art Academy of Latvia. Andersons’s insights inspired me to delve deeper into Staņa’s story, prompting me to conduct interviews with her contemporaries who were still alive at the time. Additionally, I visited the Latvian Museum of Architecture, where a portion of her archive is housed

In the years that followed, I dedicated myself to research and had the privilege of curating an exhibition showcasing Staņa’s work. The exhibition Behind the Curtain. Architect Marta Staņa, held in 2010 at two venues in Riga—the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre and the Dailes Theatre—focused on her public buildings and architectural competition entries. However, there remained a folder containing newspaper clippings and notes about her smaller projects, including private homes, summer cottages, exhibition designs, illustrations for magazines, and even designs for gravestones. I put this folder aside to explore in the future. It is also essential to know that many of her design proposals, books, photographs, and personal belongings remain in the possession of individuals residing in the houses she designed. Some documents were lost during the restructuring of archives belonging to Soviet-era organizations, and some of the recollections of her contemporaries lack supporting documentary evidence. Nevertheless, thanks to the gradual digitization of museum collections, it has become possible to compile a relatively comprehensive list of her works.

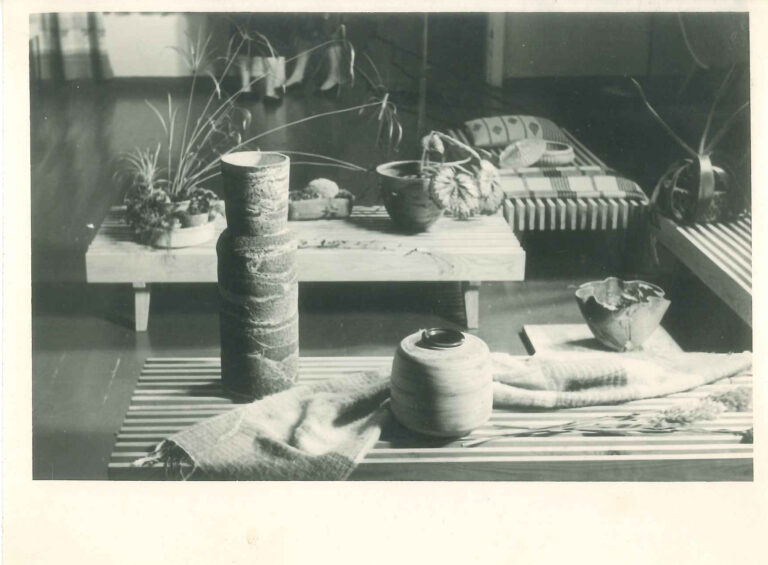

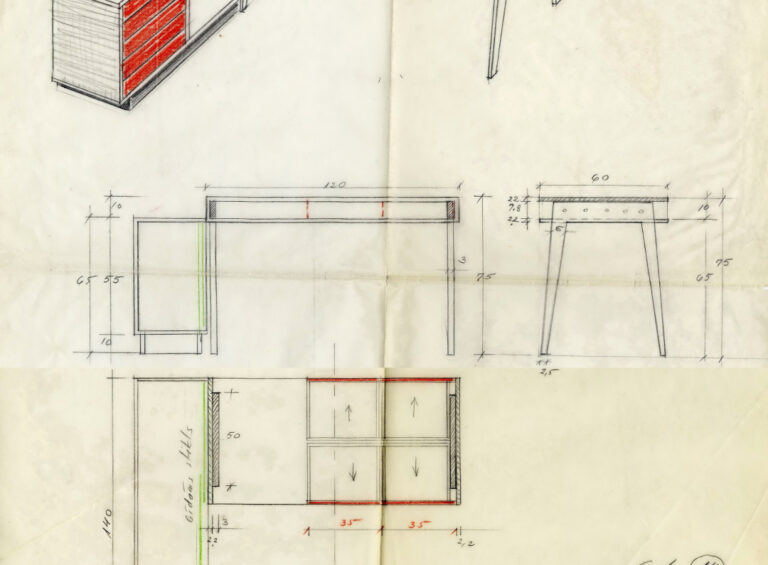

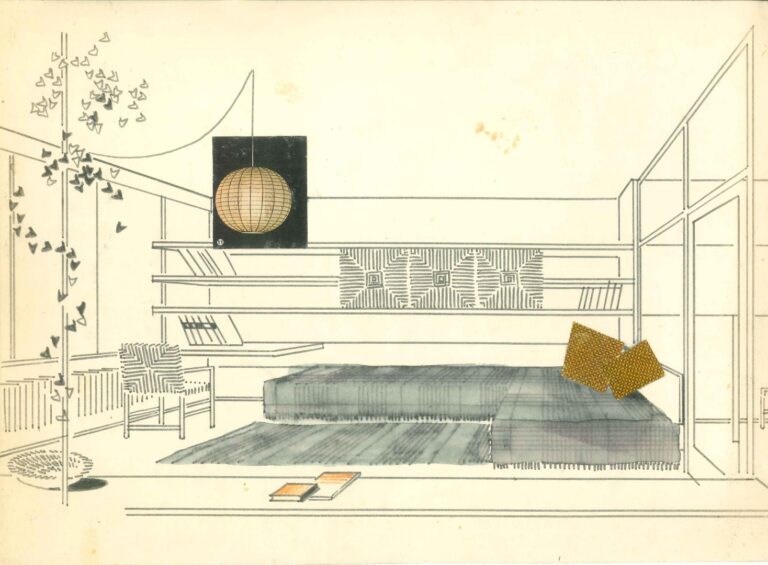

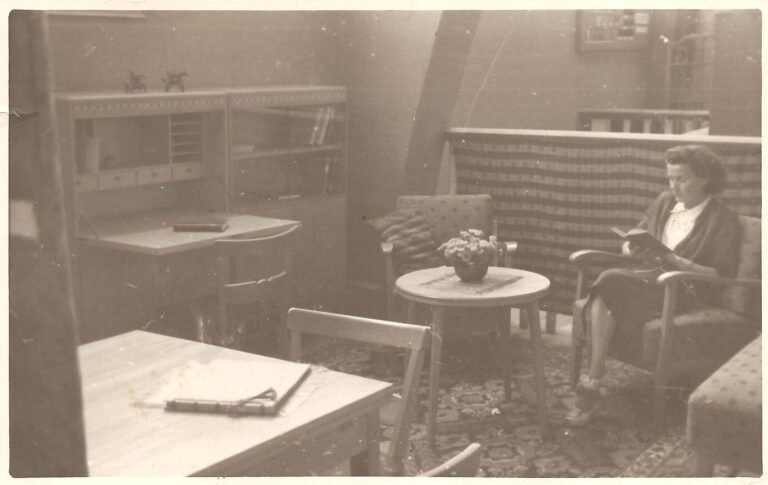

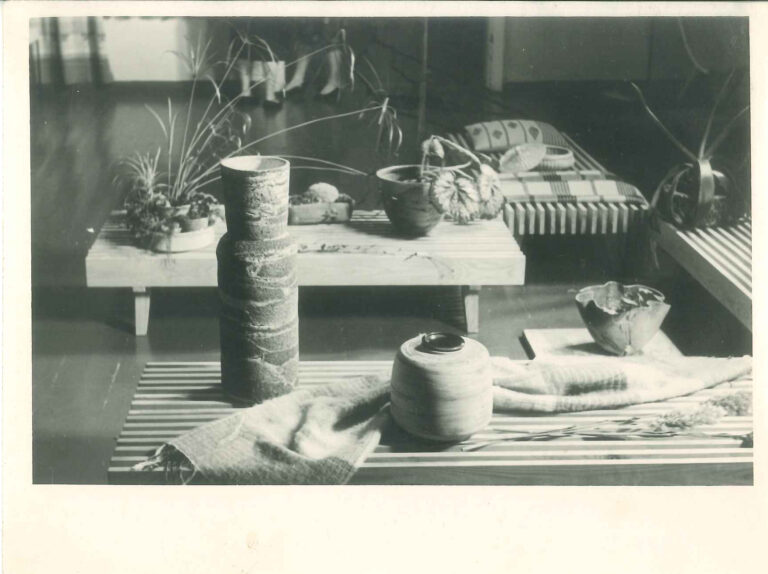

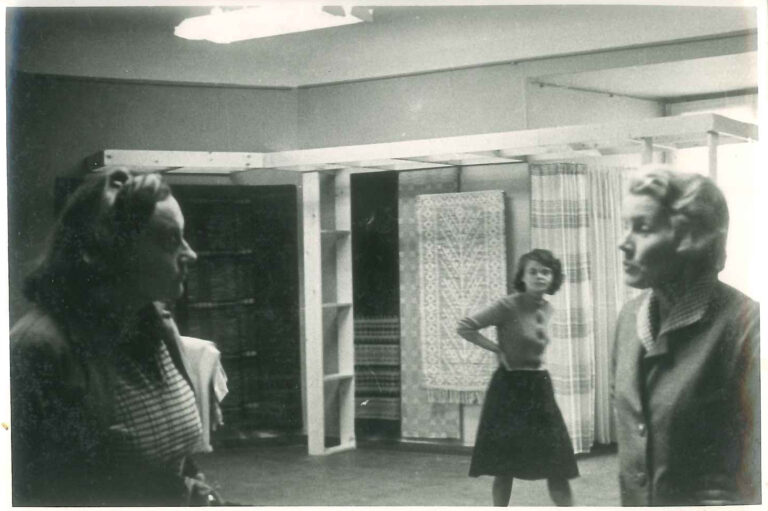

For example, the small Tukums Museum preserves a furniture set consisting of a chair, a dining table, and a sideboard, along with a rug, wall art pieces, and metal candlesticks. This set was displayed in 1962 in the annual design exhibition held at the Latvian National Museum of Art, a highly popular show, the design of which Staņa also contributed to. Her innovative approach of presenting individual furniture pieces organized in sets, juxtaposed with traditional and contemporary crafts, ceramics, and textiles, was praised by her students and critics alike. This unique integration of modern furniture within the broader context of various art forms as well as architecture was a characteristic not only of the exhibitions she designed and co-curated but also of her own designs.

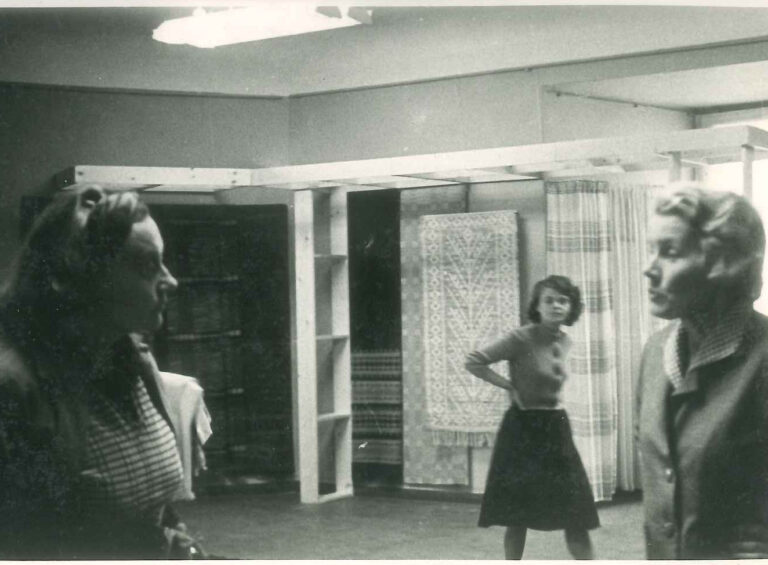

In 1963, she provided the design for an exhibition of work by her close friends and collaborators Erna Rubene (1910–1990), a respected master of traditional crafts, and Margarita Melnalksne (1909–1989), a ceramic artist. For their show, Staņa designed the general layout and furniture stands and created furniture pieces, such as tables and cabinets, to provide context for the entire exhibition.

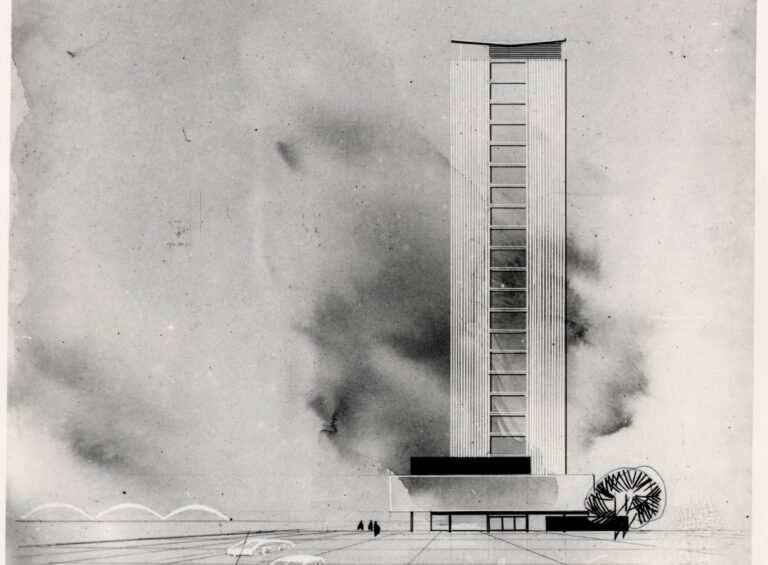

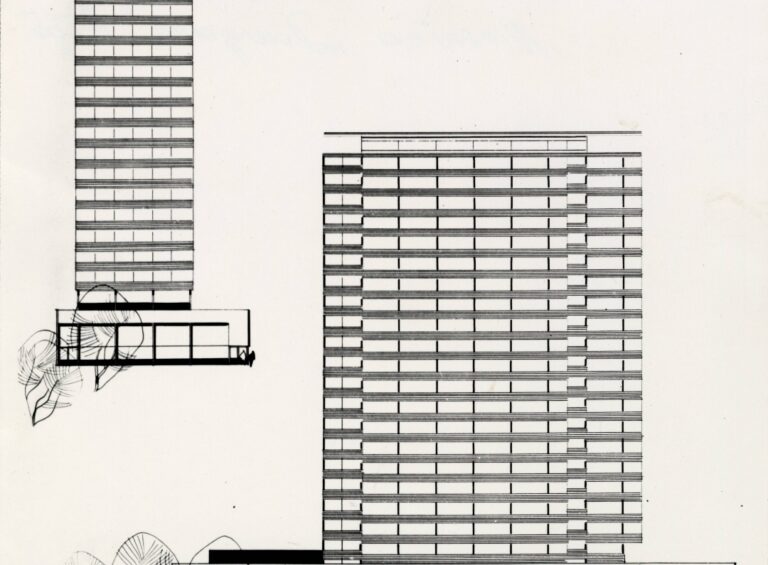

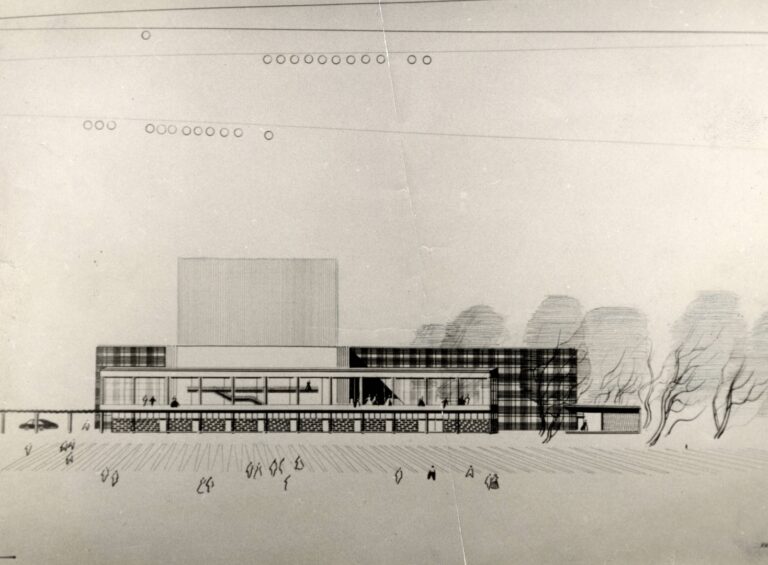

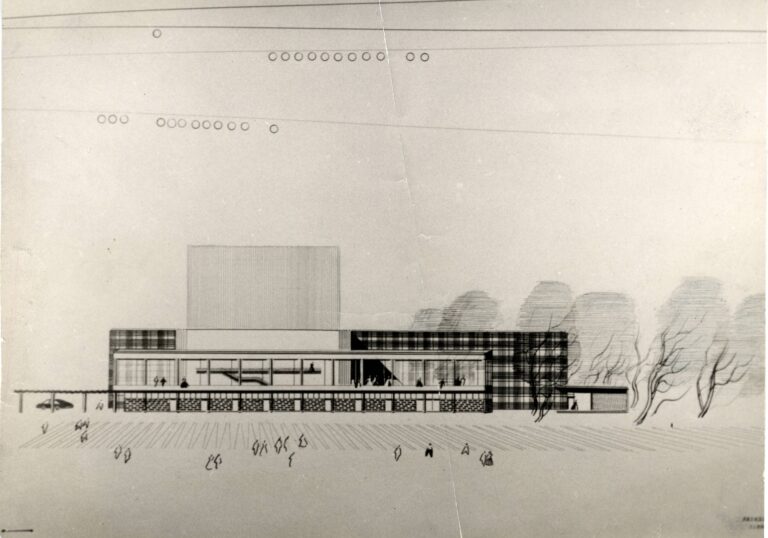

Having designed the Dailes Theatre (1959–77) in Riga, the most celebrated public building in the mid-twentieth-century modernist style in Latvia, Staņa is one of a few Latvian architects whose main architectural work built during the Soviet occupation has retained its original shape and function. Among her other notable projects are a sleek cinema extension, innovative residential building typologies, schools, private residences, and summer cottages. Unfortunately, apart from the Dailes Theatre building, all of these structures have been modified to meet contemporary functional and energy efficiency requirements. While Staņa’s legacy encompasses a significant number of ambitious projects, ranging from high-rise office buildings and apartment blocks to schools and cultural venues, many of these exist solely as blueprints and architectural competition proposals.

After earning a diploma from the Jelgava Teachers Institute, Staņa initially pursued a career in teaching before enrolling in the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Latvia in 1936. Upon graduating from the Faculty of Architecture in 1945, she was offered an assistant position under Professor Ernests Štālbergs. However, the tumultuous events of the time, including the repatriation of Baltic Germans, the initial Soviet occupation, subsequent deportations, the German occupation and persecution of Jews, and the subsequent emigration of Latvians to avoid the consequences of the Soviets’ return in 1945, greatly disrupted the established architecture school. The academic staff faced complete reconstitution, and Staņa became a member of the faculty during this process. She stood out as a talented young architect and a protégé of Štālbergs. Moreover, her previous teaching qualifications made her the sole professional educator among the other faculty graduates and other possible candidates for the job. Unfortunately, the academic community in the field of architecture, already weakened by the circumstances, suffered another blow when Staņa and her professor were dismissed from their positions at the University of Latvia during the academic purges of 1949–50. Immediately after that, the Faculty of Architecture was also closed, completely destroying the national school of architecture. Architecture was further taught at the Faculty of Building Construction at Riga Technical University.

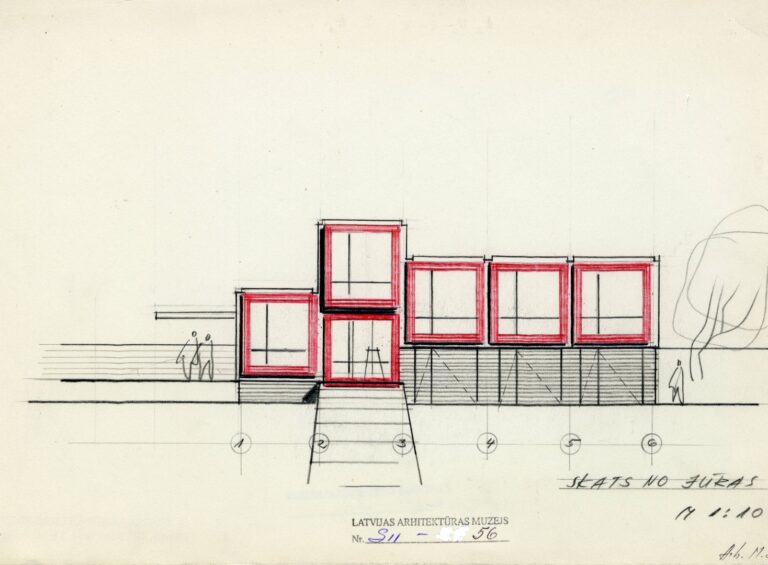

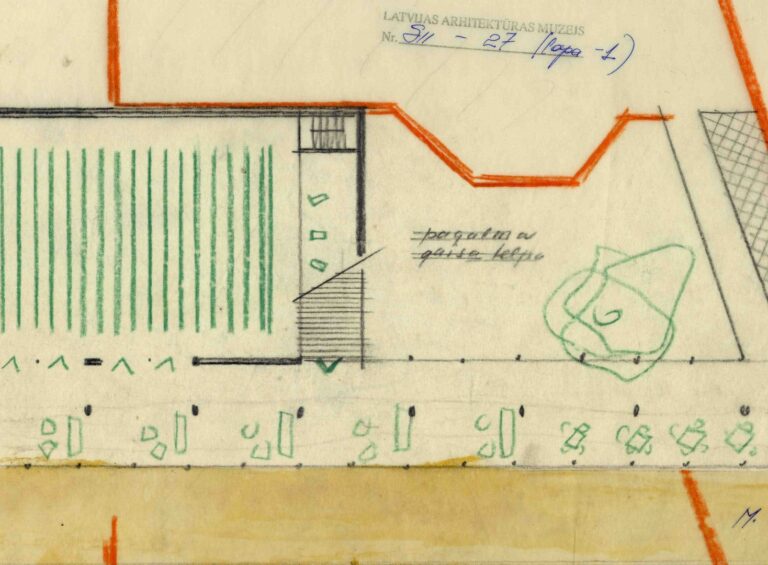

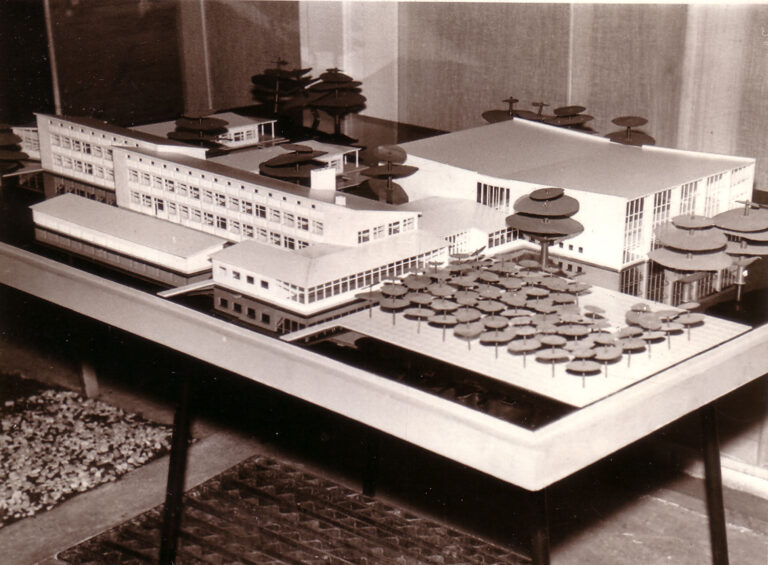

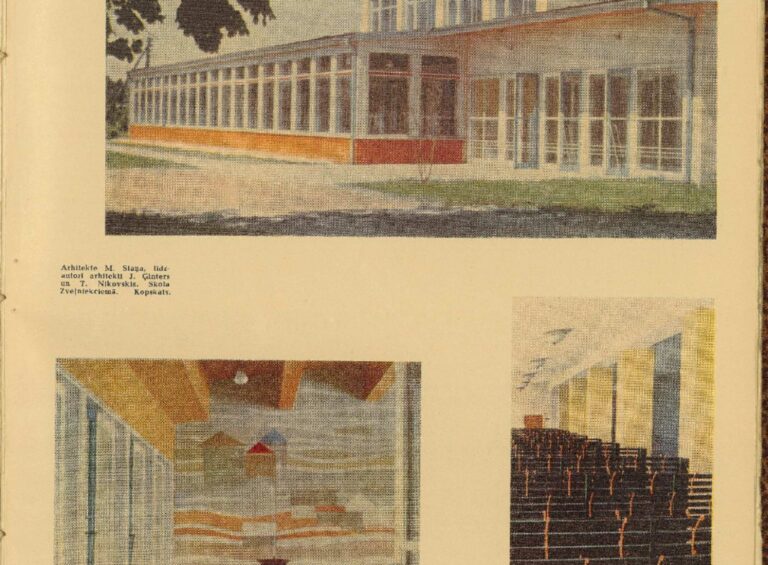

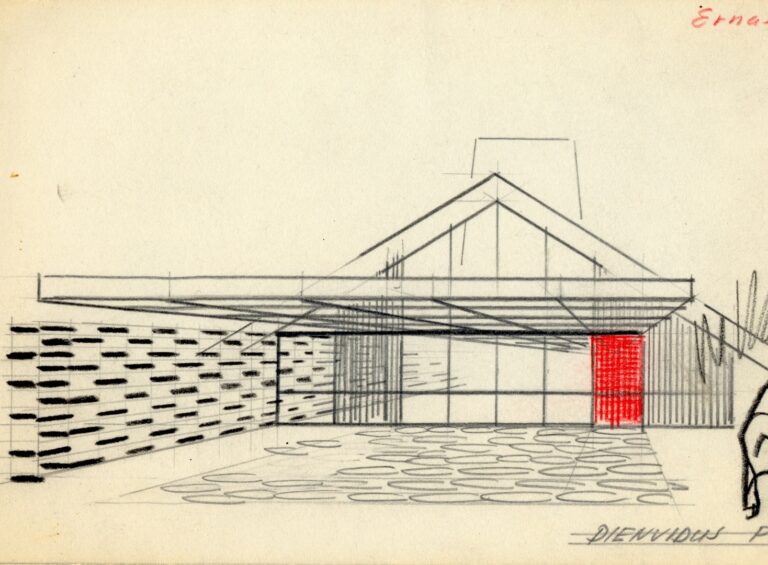

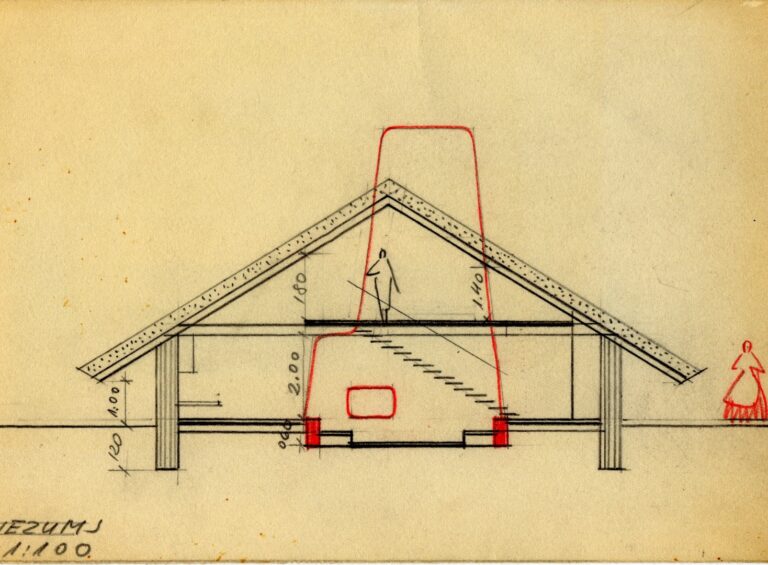

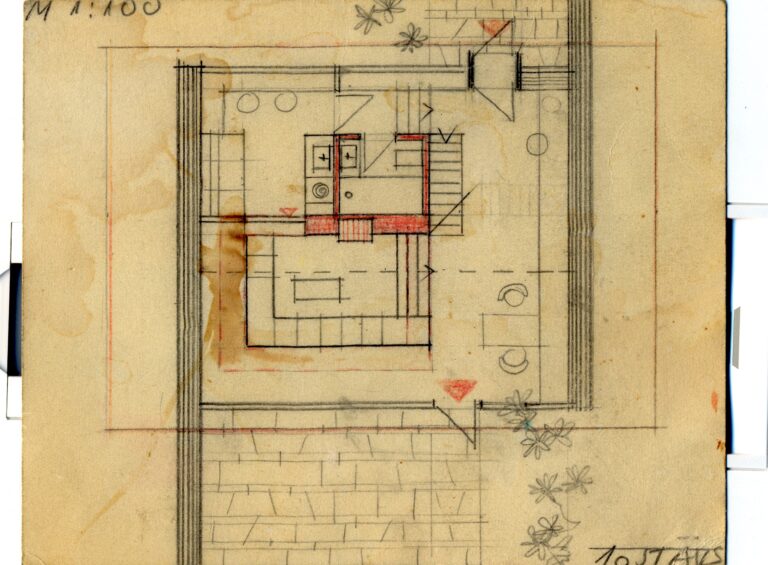

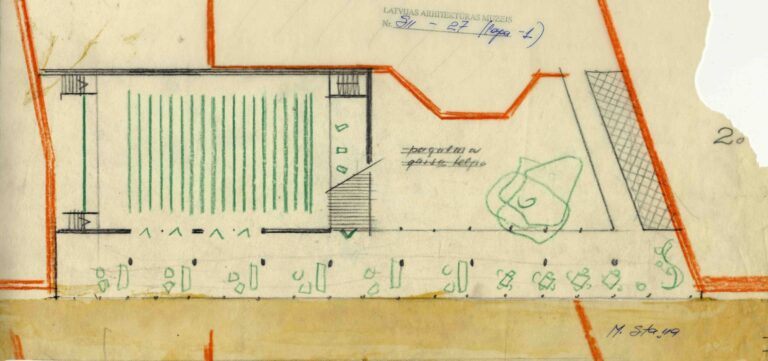

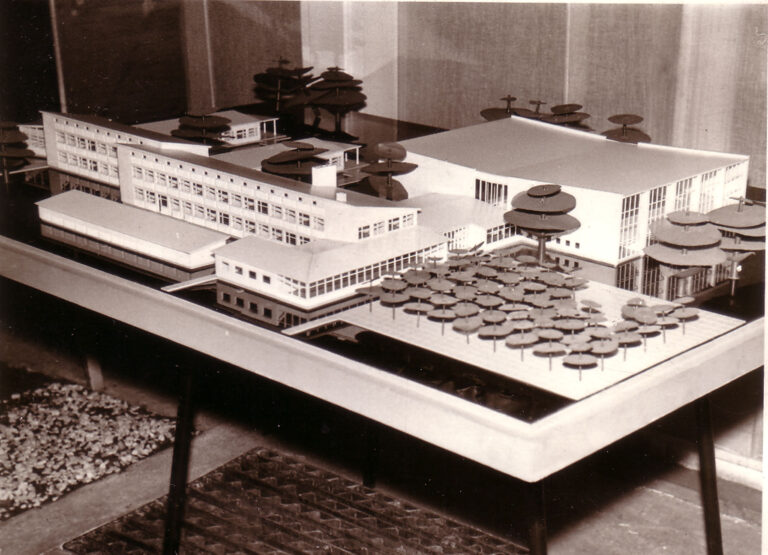

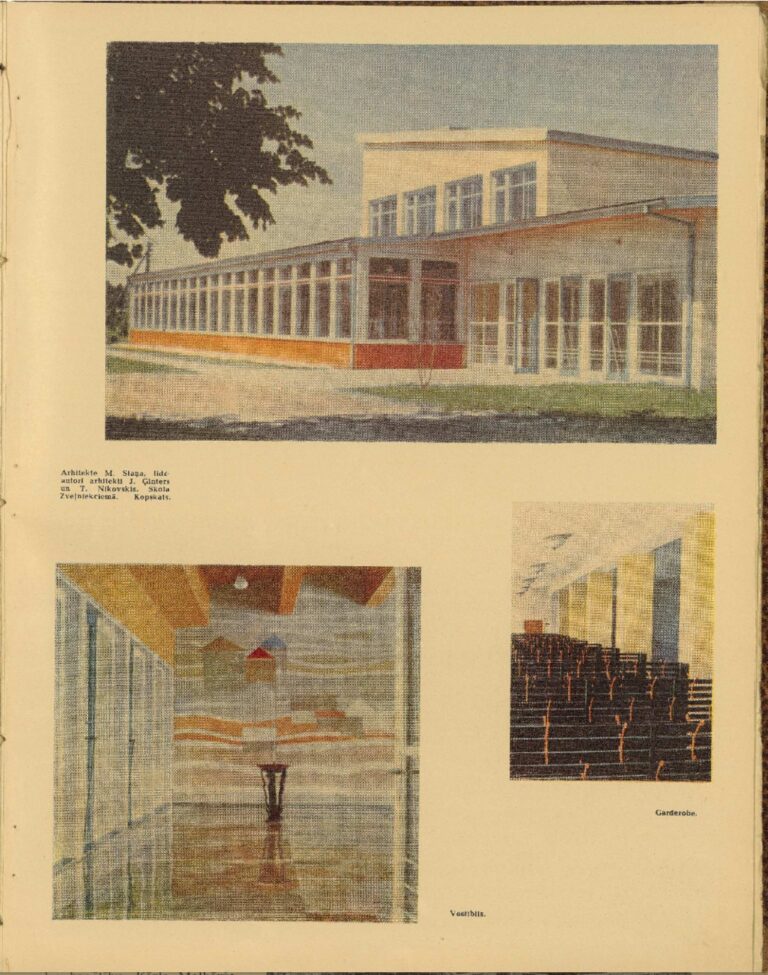

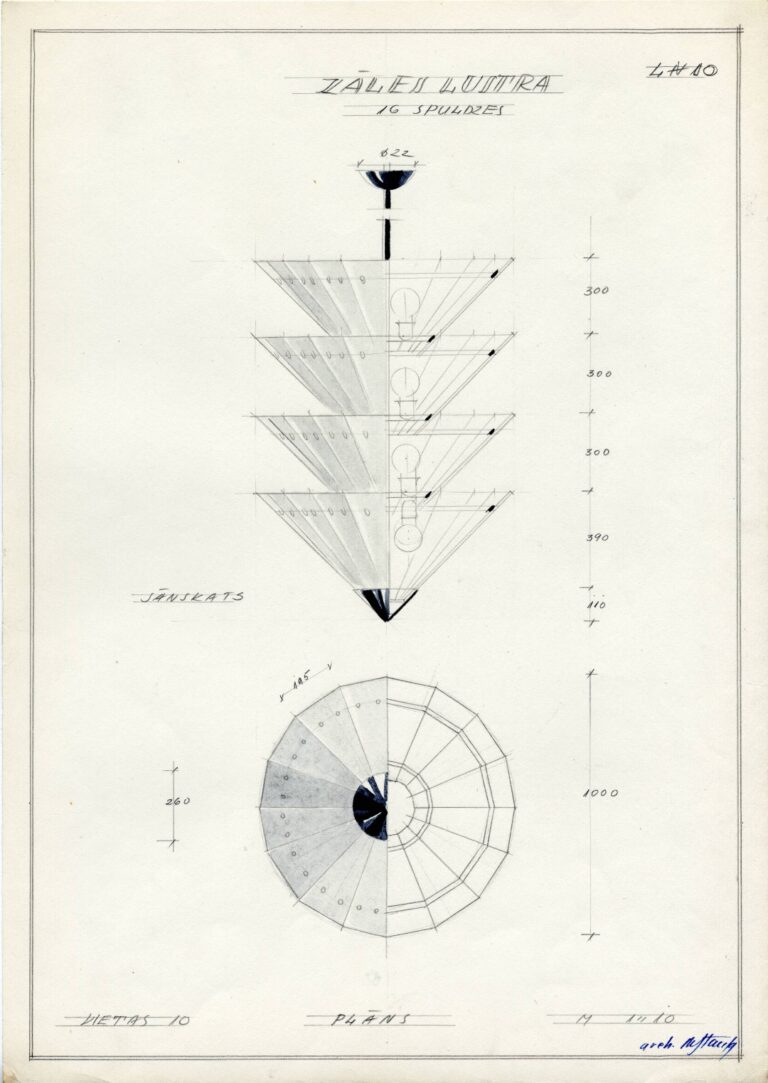

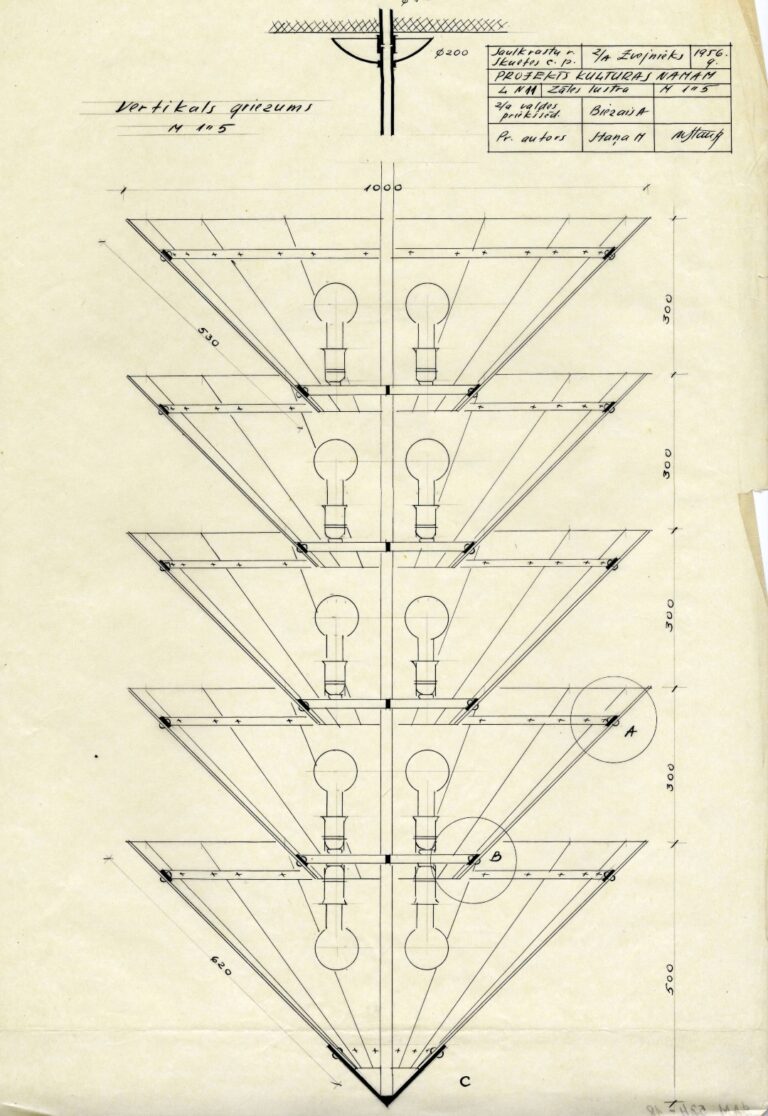

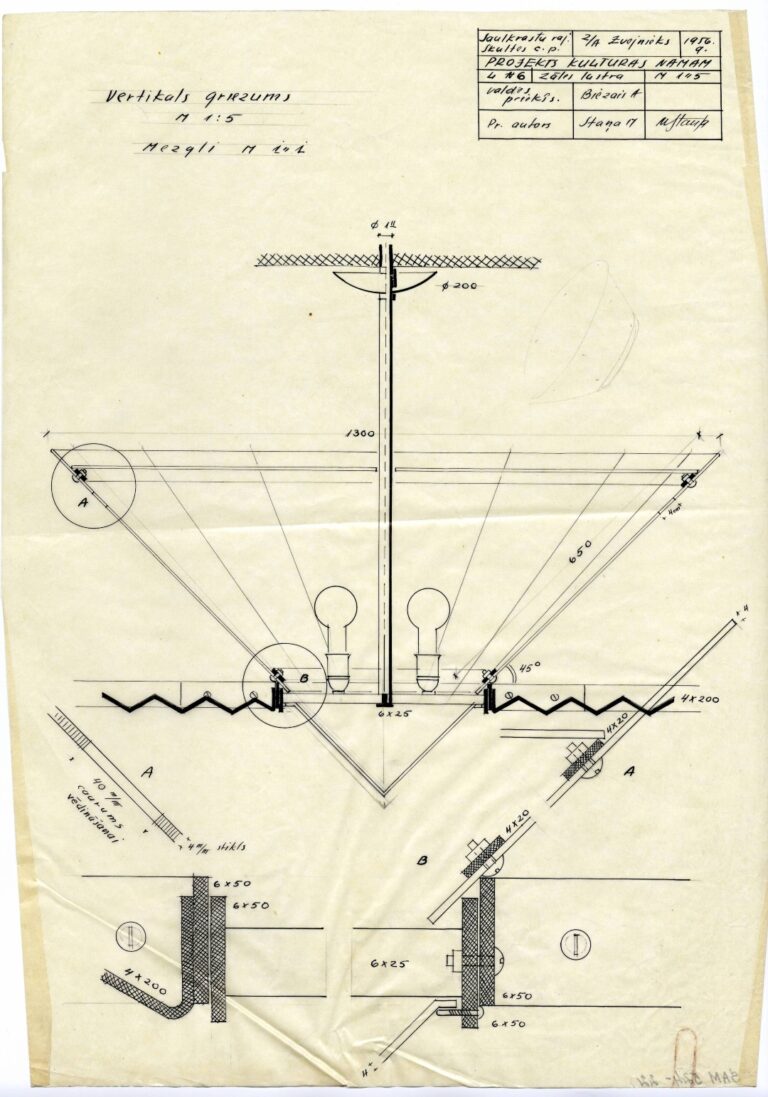

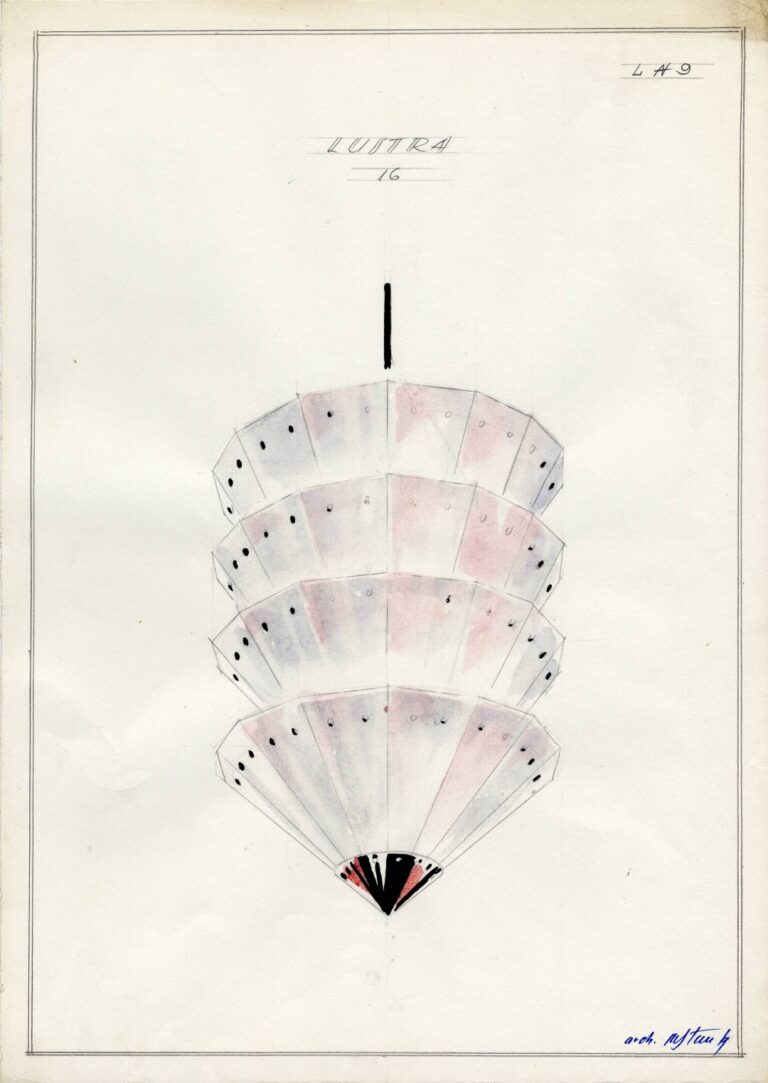

During most of the 1950s, Staņa was engaged in a significant project for the remote fishermen’s kolkhoz, a newly made Soviet collective farm, in the coastal village of Skulte (Zvejniekciems), now part of Saulkrasti city. Her involvement included designing a master plan for the village, encompassing various facilities such as a workers’ club, a school, and a low-rise housing complex for teachers. The kolkhoz, which emerged from a prosperous fishermen’s cooperative that had been nationalized by the Soviets, possessed substantial resources and ambitions, enabling the commissioning of an entire village.

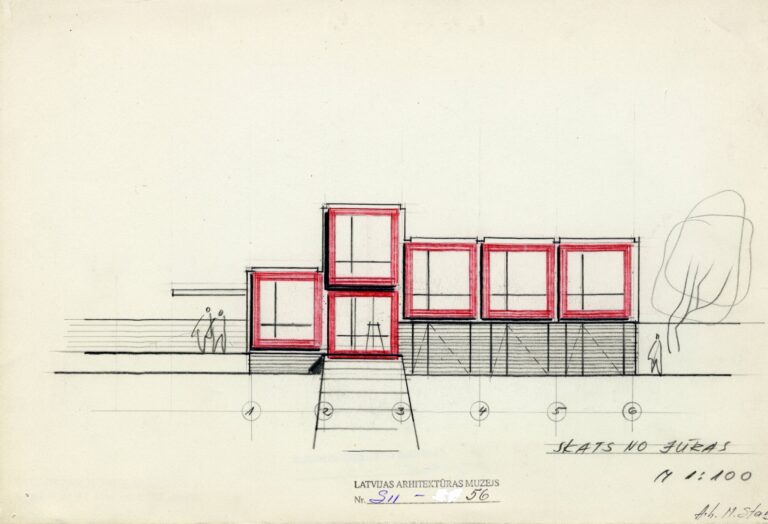

Initially, Staņa’s early proposals for the village adhered to the obligatory Stalinist architectural style prevalent at the time. However, in the mid-1950s, she embraced a newfound liberation inspired by the sweeping modernisation throughout the Soviet Union. This shift allowed her to explore innovative approaches in her designs. One noteworthy project that exemplified this progressive mindset was the school in Zvejniekciems. Developed immediately after the club, showcasing the canonical Stalinist architecture, the school design offered pioneering qualities, such as a horizontally arranged layout, with distinct volumes dedicated to each function. Abundant natural light flooded the learning spaces, creating an inviting environment. Furthermore, the school offered direct access to the surrounding nature, fostering a harmonious connection between the built environment and the outdoors.

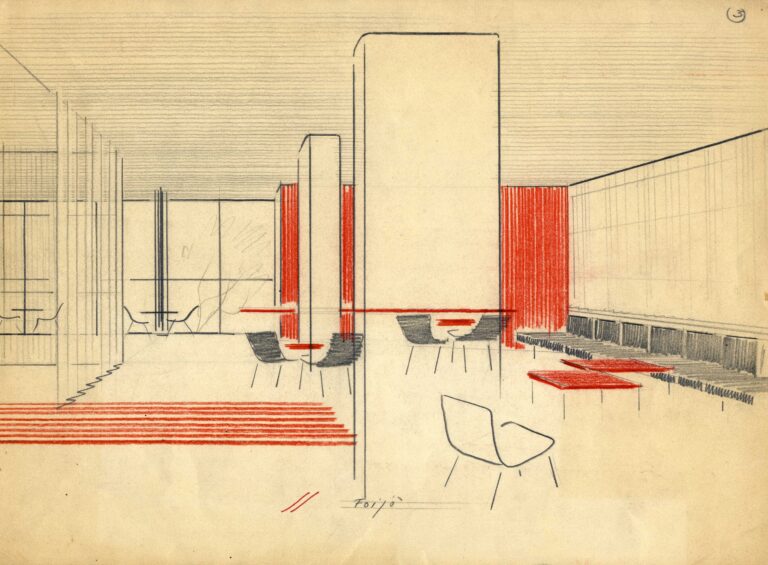

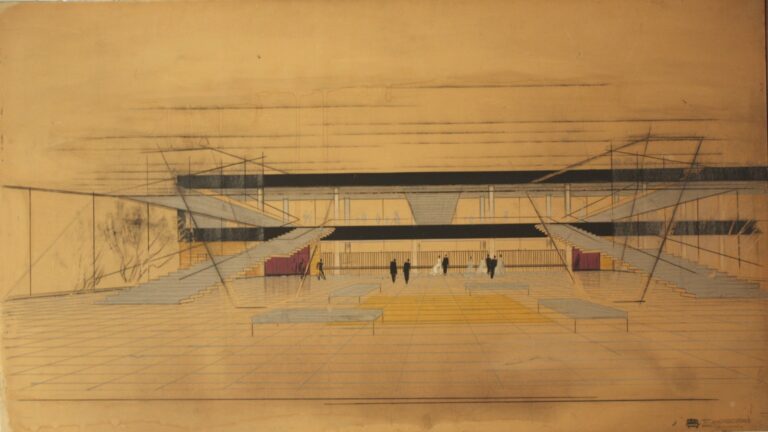

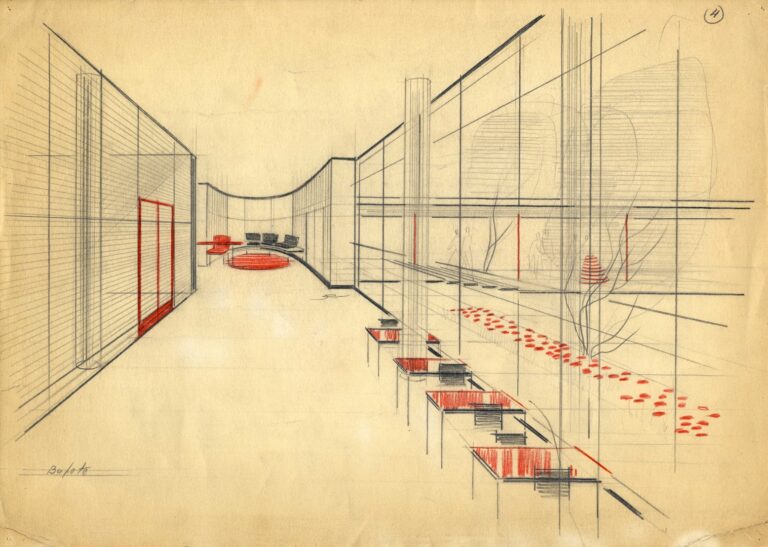

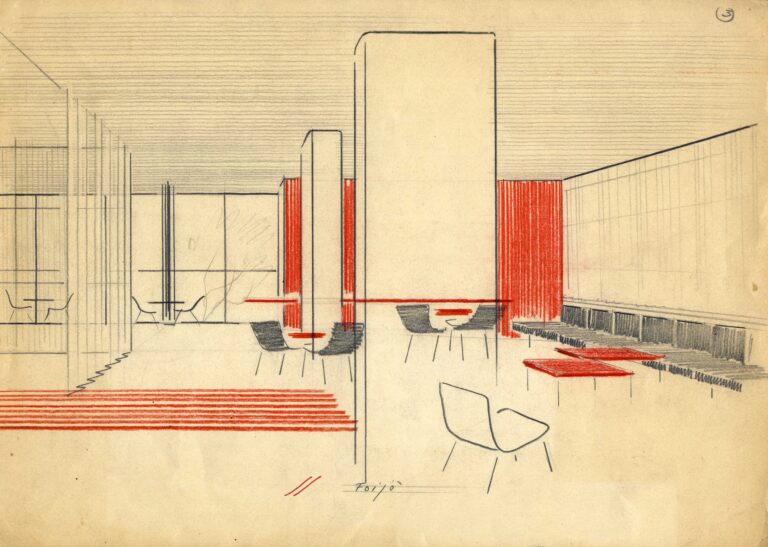

Following her victory in the Dailes Theatre building competition in 1959, Marta Staņa joined the State Design Institute in 1960, where she dedicated herself to the ongoing design of the theatre until her final days. Her proposal with the main foyer’s horizontal volume situated on the second level remains unique within the context of Riga, where historical architecture predominantly prevails. By incorporating wide windows in foyers and designing a hall capable of accommodating 1,000 audience seats, Staņa introduced a fundamentally new architectural and theatrical experience opening it up to the city. Unfortunately, in line with the typical constraints of the Soviet economy, the construction of the theatre spanned 18 years due to changes and material shortages. However, despite modifications made throughout the design process, the architect’s original idea remained intact. The architecture of the theatre encompassed not only the building itself but also the surrounding public space, which underwent renovations in 2023 by MADE architects. This serves as a rare example of a building constructed during the Soviet era that has not only retained its original purpose but also complies with modern standards of public space and accessibility.

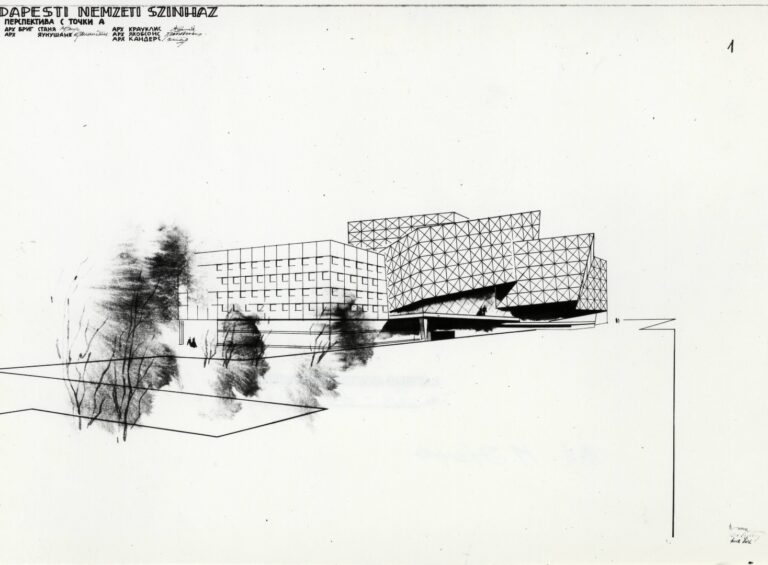

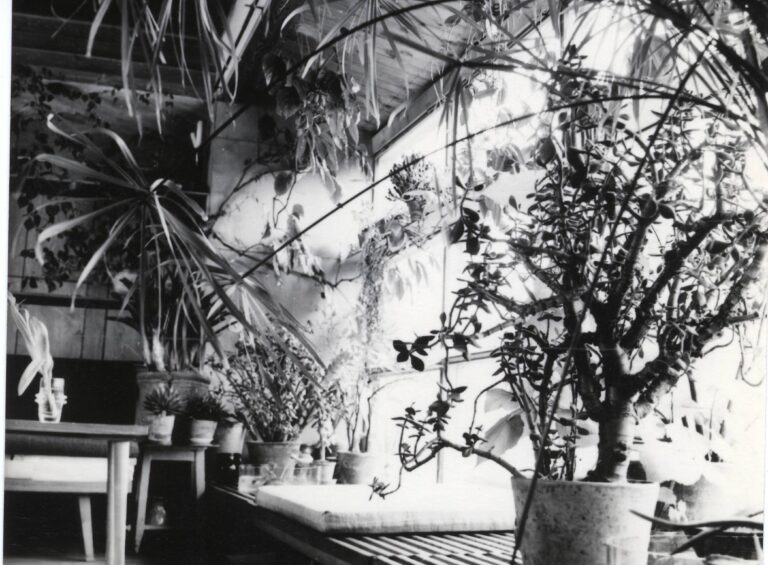

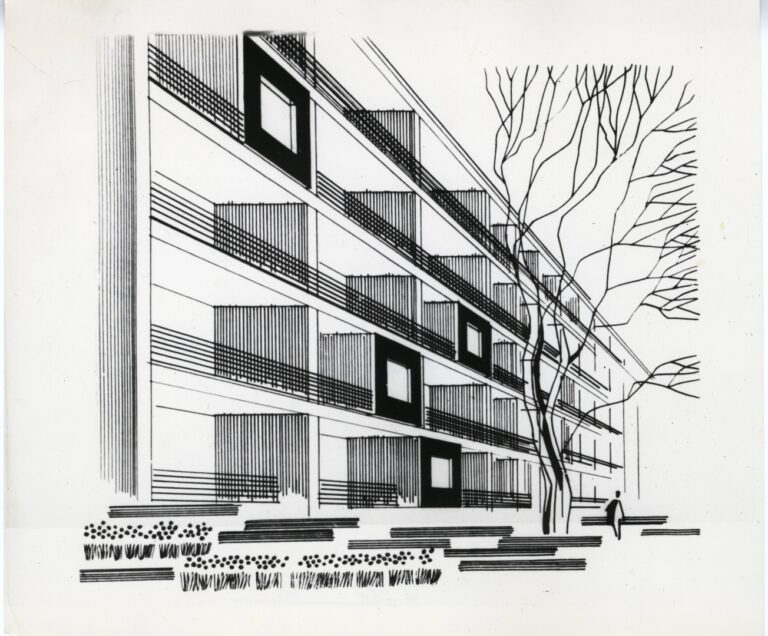

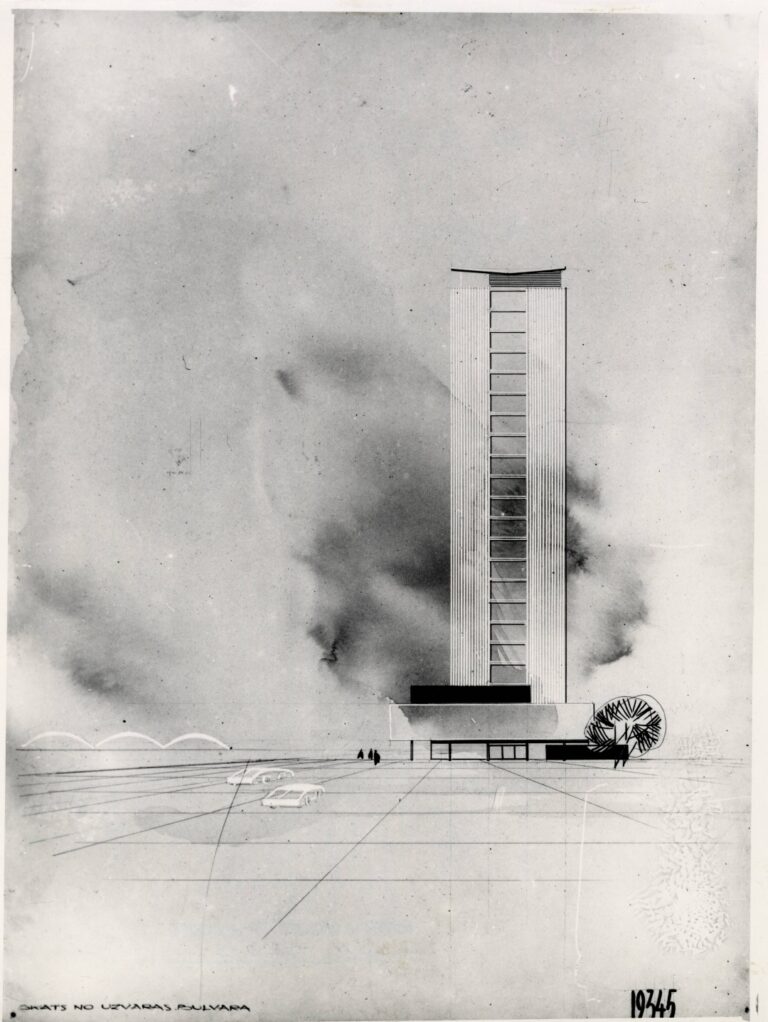

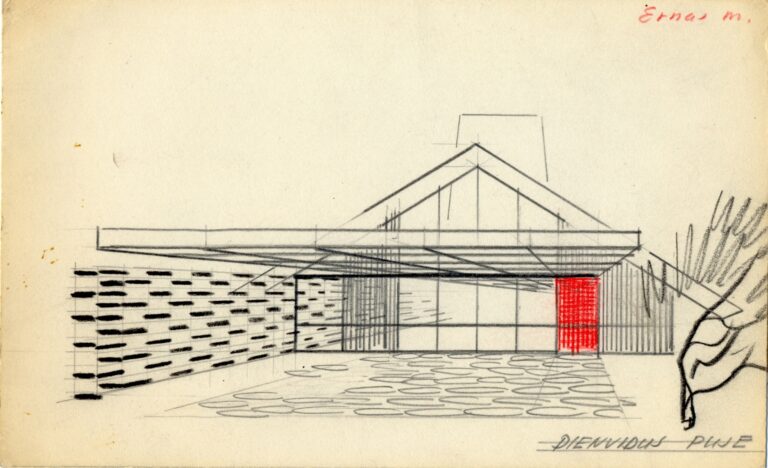

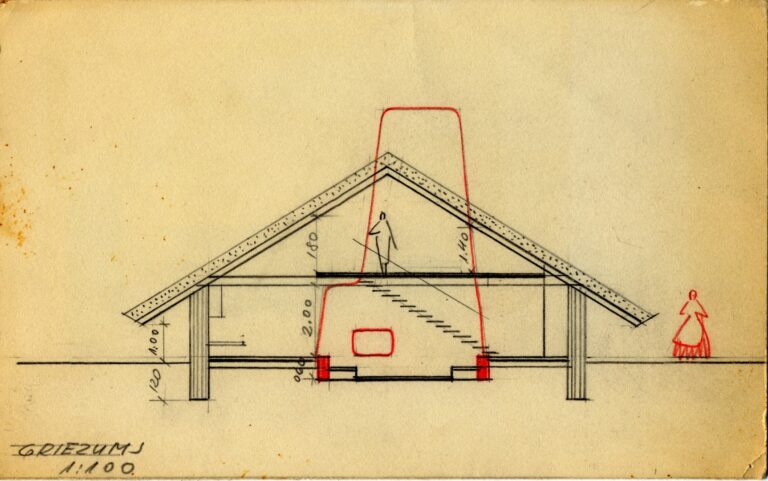

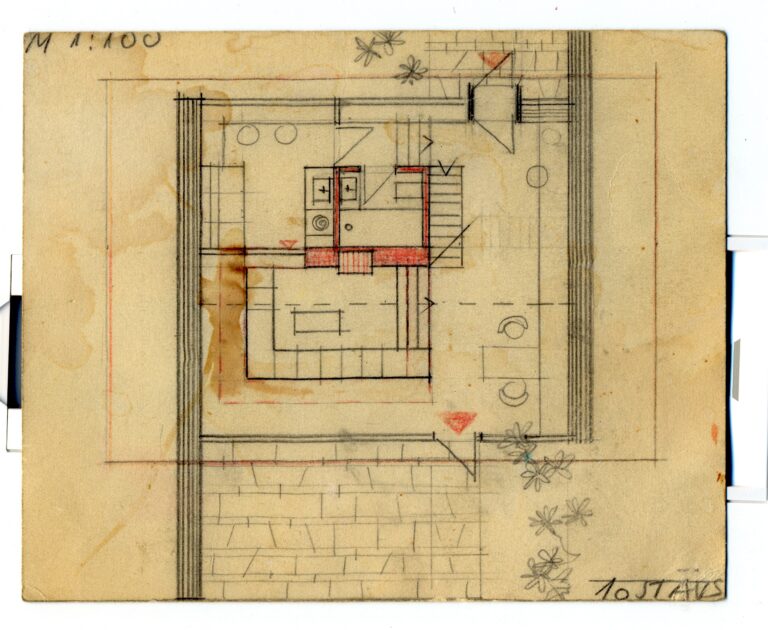

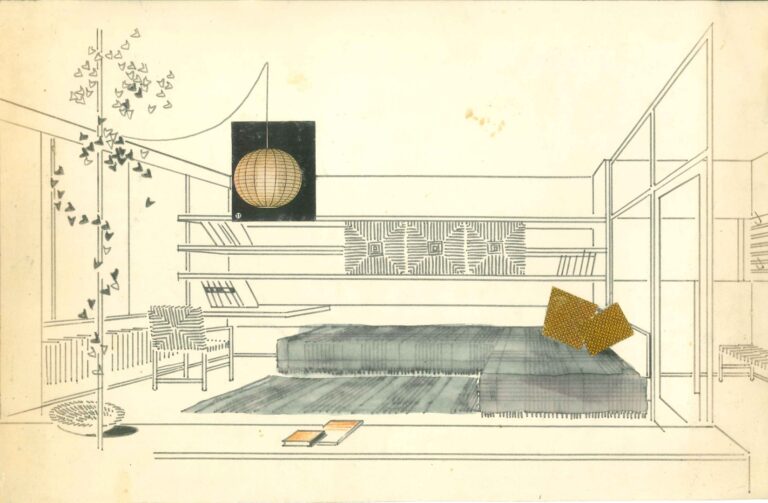

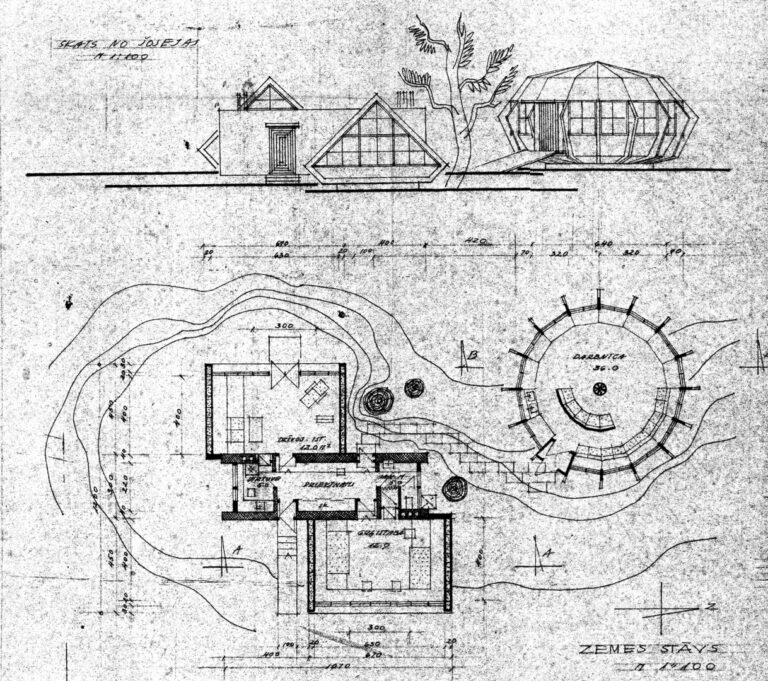

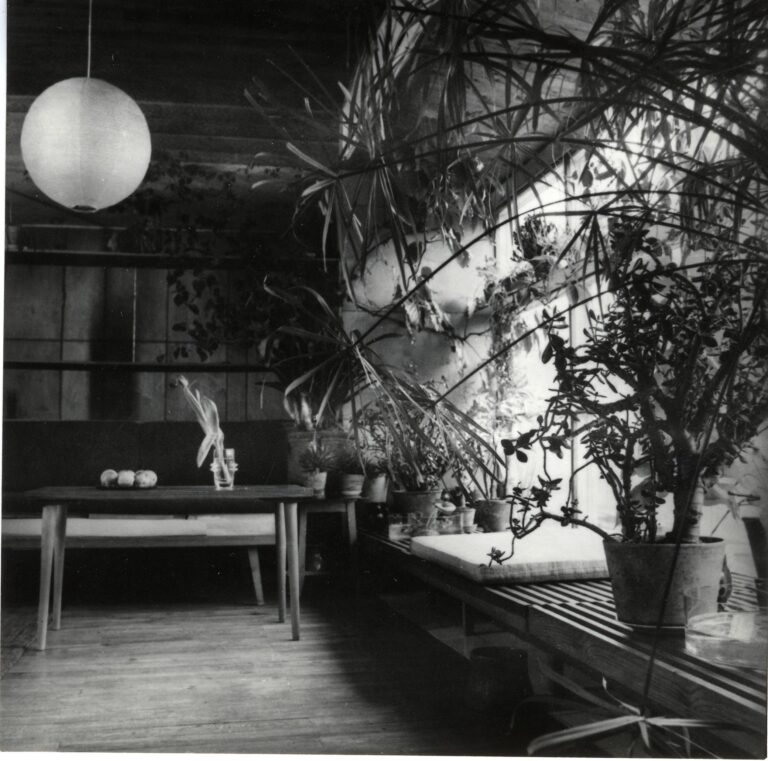

During her tenure at the institute, Staņa actively participated in numerous local and international design competitions, earning the admiration of colleagues for her ability to swiftly translate ideas into drawings, proving her talent for architecture and exceptional artistic skills. Among other notable works during her time at the institute were experimental apartment blocks characterized by spacious balconies, efficient utilization of space and natural light, and unconventional arrangements of facade panels. Additionally, outside of her official working hours, she passionately designed private homes and summer cottages for her colleagues and friends. These projects, created on limited budgets, exemplified Staņa’s remarkable ability to work harmoniously with available, low-quality materials, often repurposing leftover resources while maintaining a connection with nature.

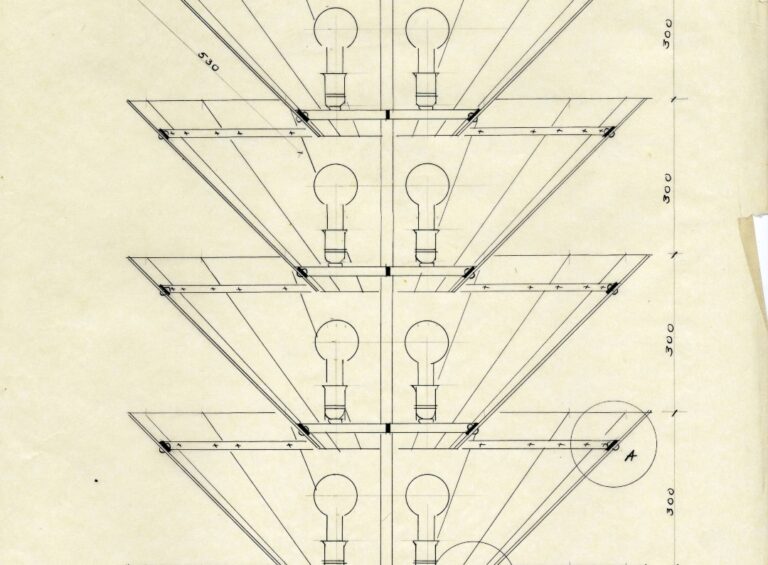

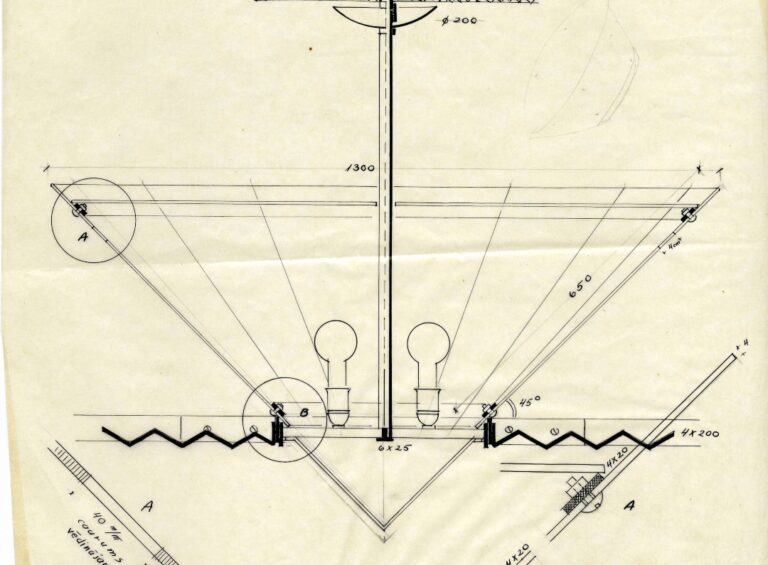

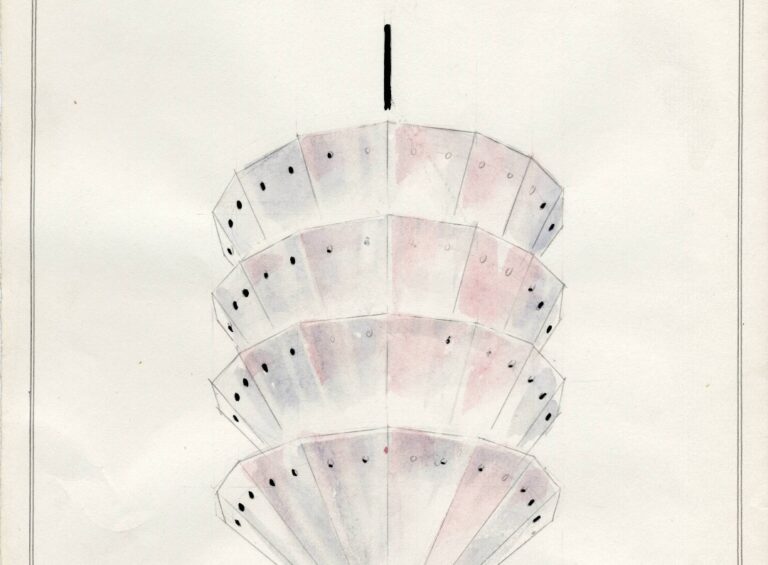

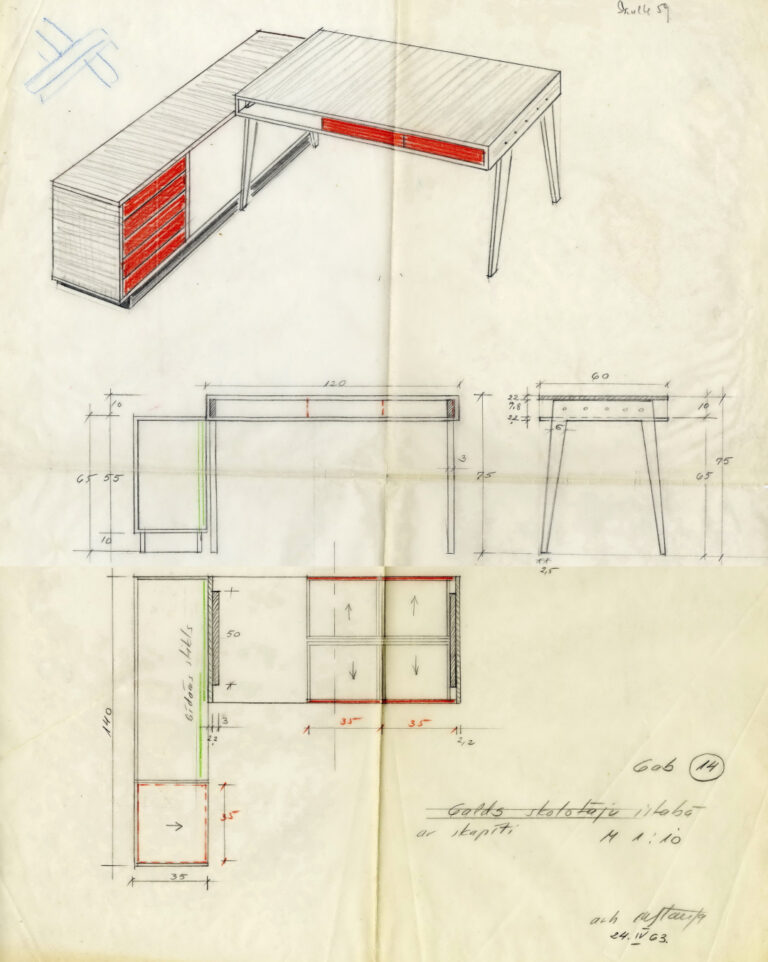

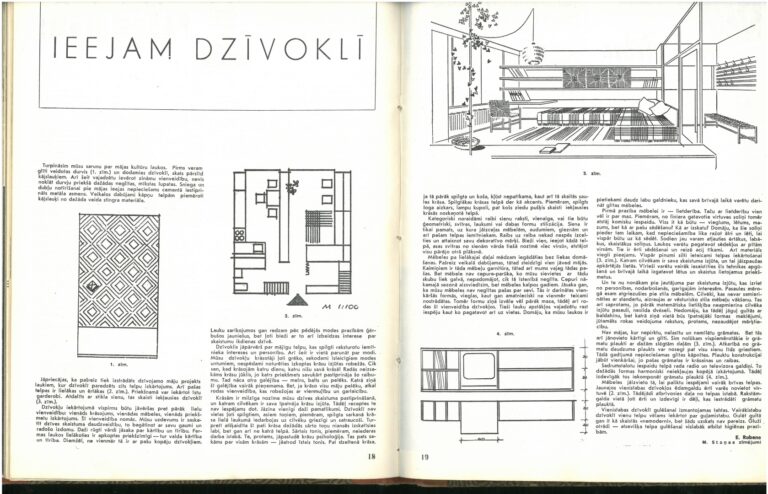

For most of her projects, Staņa also provided interior design ideas, including furniture, lighting, and textiles. Staņa’s passion for illustration led her to collaborate with magazines, where together with her friend Erna Rubene she shared their expertise through illustrated advice on modern living. Her artistic skills and a keen eye for design were instrumental in providing practical and visually appealing suggestions to readers.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Staņa also dedicated herself to teaching, primarily within the interior design departments of Riga Design School and the Art Academy of Latvia. Although teaching may have held a lower status in terms of prestige, it was highly regarded by students who valued her unique guidance and expertise. Staņa’s educational method incorporated the concept of working with space and its objects as a cohesive ensemble, showcasing her approach to complex and rational thinking. She consistently encouraged her students to strive for excellence, offered constant encouragement and provided inspiration. Although she did not receiving any awards during her lifetime, her students, such as stage designer Andris Freibergs (1938–2022), who has mentored a new generation of internationally acclaimed stage designers, attest to the enduring effectiveness of her teaching methods and her talent as an educator: “I was so taken by her. I joined the interior design department of the Art Academy because Marta Staņa started teaching there.”1https://www.neputns.lv/en/products/andris-freiberg Margarita Zieda. Andris Freibergs. Rīga: Neputns, 2015. Many young designers had the opportunity to prove themselves by contributing to Staņa’s architectural projects, for example, in Zvejniekciems, where both the club and school buildings display graduation works, such as stained glass windows, ceramics and textiles, of Riga Art and Design School students.

Staņa died of cancer in 1972 and her career as an architect was relatively brief, lasting less than twenty years. Her work is characterized by a distinct clarity of vision, scope, and bold lines, skillfully incorporating people in motion and elements of nature. She viewed architecture, both in practice and education, as a unified approach to space, where architecture harmoniously interacts with the surrounding environment, interior spaces, and art objects within them. Staņa has not left a written theoretical legacy. Even in discussions held at the Latvian Association of Architects, she participated with simple, rational comments. She also helped her colleagues practically, even working in several teams during one competition. Staņa was not able to see the Dailes theatre building completed, nor was she able to live in the house and work in the studio she designed and started to build for herself by the Baltic Sea. Many of her ideas remained only as drawings. “I was born too soon. No one can build my ideas,”2From the author’s interview with Staņa’s former colleague at the Design Institute architect Vera Savisko in 2003.she has said.

The assignment of roles to female architects was one of the many architectural histories explored during the 2019 exhibition A Room of One’s Own at the Estonian Architecture Museum3https://arhitektuurimuuseum.ee/en/naitus/a-room-of-ones-own-feminist-questions-about-architecture/ in Tallinn. The curators raised questions about authorship in architectural collaborations and the distribution of awards in the field. In 1967, Staņa completed a mandatory biography questionnaire before her trip to former Czechoslovakia. She confirmed that it would be her first trip abroad and that she had never received awards for her work. While the Soviet labour market maintained equality between men and women, awards and participation in such trips were privileges reserved for male colleagues with prominent positions and Communist Party membership.

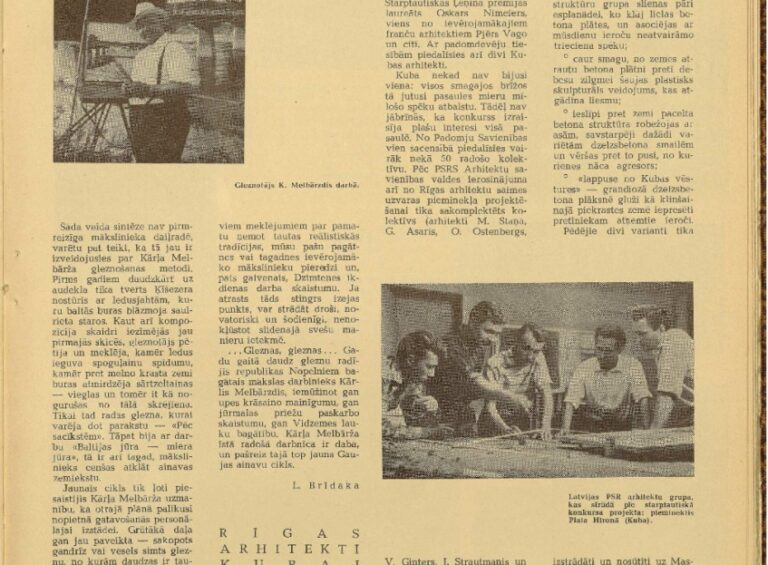

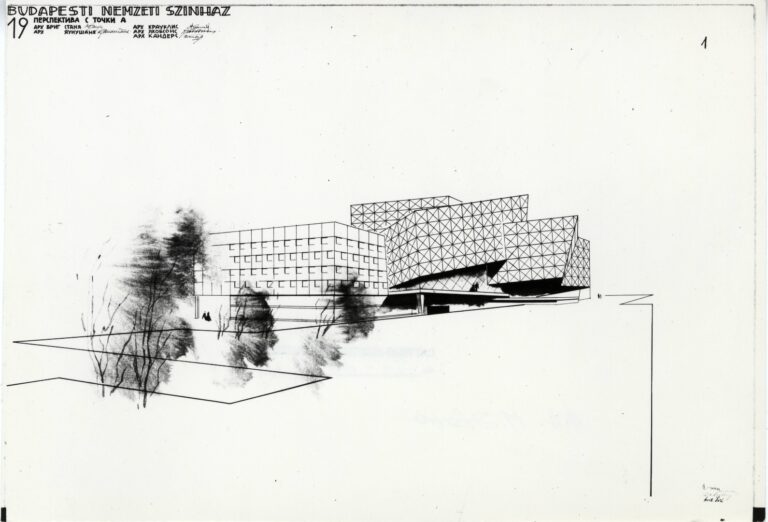

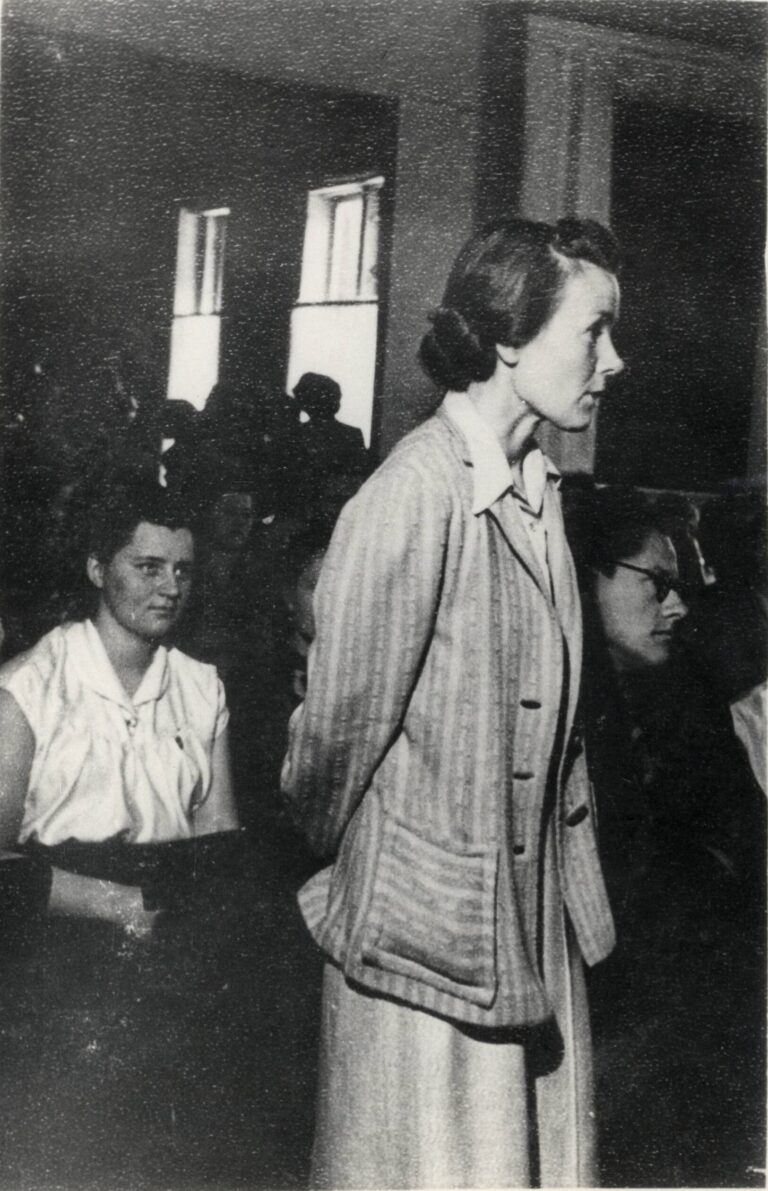

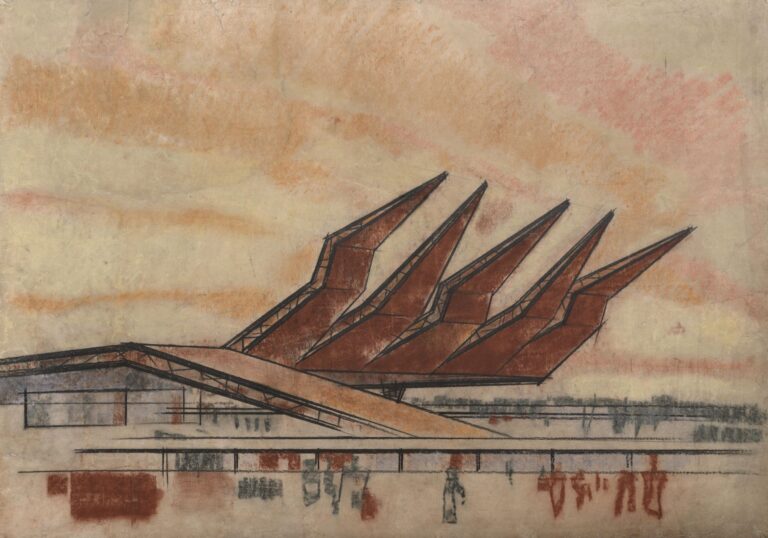

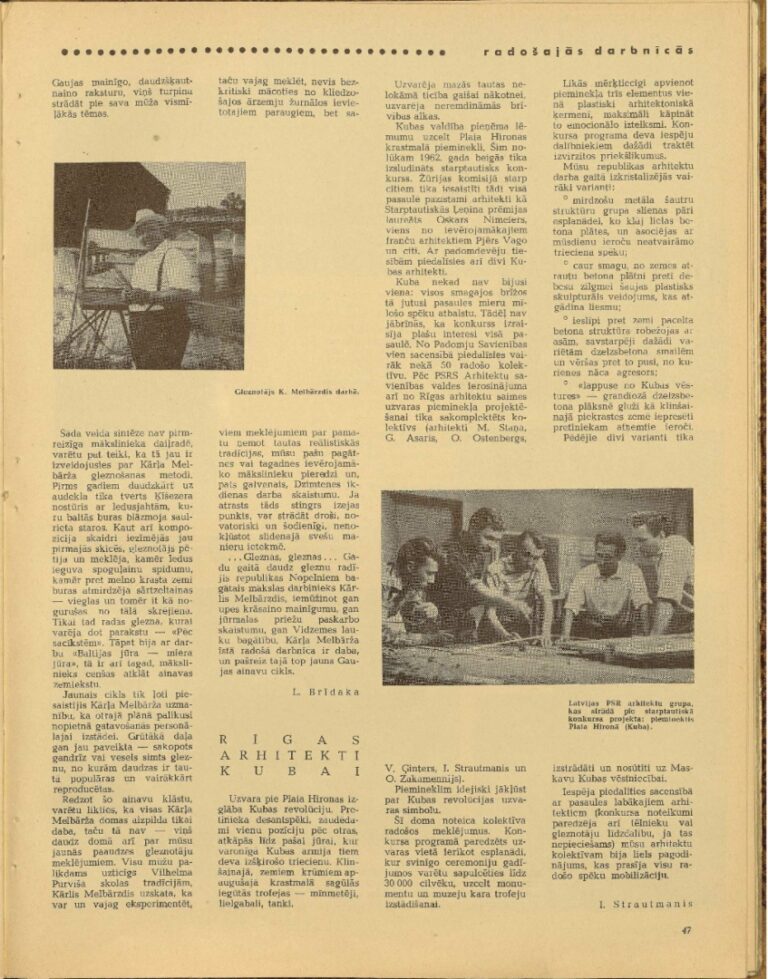

Regarding work placements, every architecture student was guaranteed a job at one of the State Design Institutes. However, not everyone managed to secure a position at the prestigious City division, which offered the opportunity to work on large public buildings. Women architects were often sent to remote locations, the countryside, or employed in other industries, such as road design. Female architects also played valuable roles in competitions, yet authorship and recognition frequently favoured male leaders. For instance, in 1963, an article4Māksla, Nr.3 (01.07.1963) in the magazine Māksla reported the participation of the Latvian team in the international competition for the monument in Playa Girón, Cuba. Similar to other competitions, a team of renowned professionals was formed, later working on Staņa’s idea. However, the accompanying photograph only featured her male companions. In that same year, one of the authors, Ivars Strautmanis, highlighted this competition as a personal achievement in the newspaper Rīgas Balss5Rīgas Balss, Nr.307 (30.12.1963), without mentioning other team members. Both articles in this case reflect the male perspective of the author, photographer, and editor. Such articles, omitting co-authors, reinforce the perception of authorship, perpetuating it in subsequent publications and conversations to this day. Additionally, it was common practice not to invite female team members to present projects on television or in documentaries, which were abundant to promote Soviet propaganda through culture. When women managed to appear on screen, they were often given the role of attractive background or exhibition visitors.

However, Staņa did not require an official title to earn recognition and praise from art and cultural circles. Her projects may have been unrealised or small in scale, budget, and impact on the official architectural agenda, nevertheless, her position on the periphery led her to work on cultural projects. These projects, though modest, have recently become accessible for examination thanks to the digitalization efforts of museums and archives. It has been a tremendous pleasure to discover footage of the interior she designed for the editorial office of Māksla magazine or blueprints of storage cabinets created for the Museum of Literature and Music while writing this article and adding two more works to her portfolio. In the Soviet Union, architects were not rewarded with prizes or bonuses for empowering the female community, designing museum cabinets, or experimenting with houses for private clients using leftover construction materials. Staņa’s architecture, indeed, exemplified empathy and embodied the paradigms of our time, transcending the boundaries of the 20th century.

- 1https://www.neputns.lv/en/products/andris-freiberg Margarita Zieda. Andris Freibergs. Rīga: Neputns, 2015.

- 2From the author’s interview with Staņa’s former colleague at the Design Institute architect Vera Savisko in 2003.

- 3https://arhitektuurimuuseum.ee/en/naitus/a-room-of-ones-own-feminist-questions-about-architecture/

- 4Māksla, Nr.3 (01.07.1963)

- 5Rīgas Balss, Nr.307 (30.12.1963)