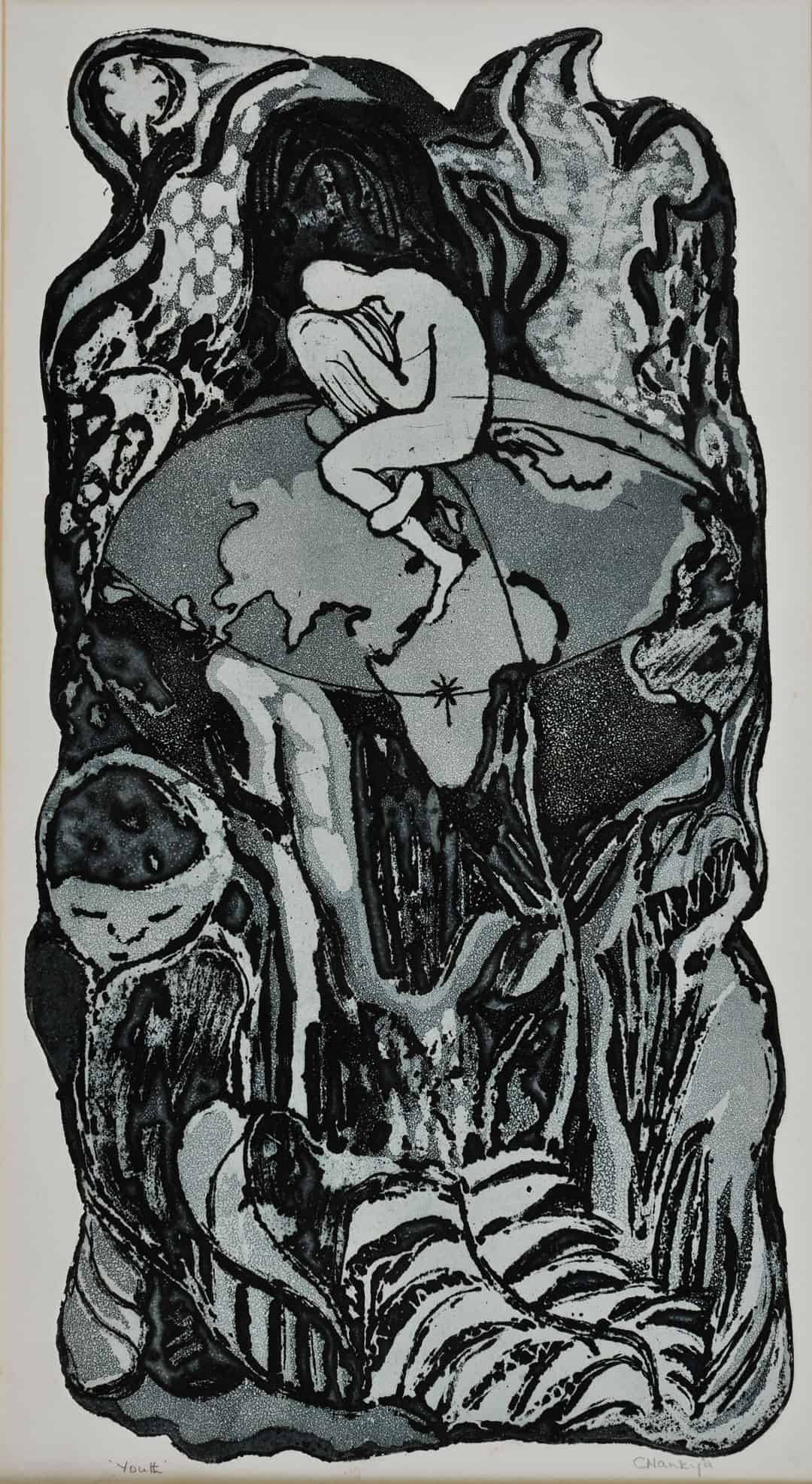

In the etching Youth (1965; fig. 1), a contemplative figure sits atop a globe, head resting on a knee, legs twisted together, arms tucked protectively into the body. The figure’s head, which is turned inward, counterposes the frontal, downcast face in the lower left foreground. It is this face that the etching’s maker, Ugandan artist and professor Catherine Nankya Katonoko Gombe, states was the origin point for the work itself, its tender melancholy invoking the difficulties of her childhood following “the death of [her] father at a tender age and the struggle to continue with education.”1I am grateful to Professor Catherine Gombe for sharing her thoughts on this work during the preparation of the exhibition Dar to Dunoon: Modern African Art from the Argyll Collection (2021). Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021. Youth is one of three prints pulled from plates etched by Gombe in her final year in the printmaking course offered by the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts (MTSIFA) at Makerere University, then part of the University of East Africa.2This was a short-lived, multi-sited institutional configuration in operation from 1963 to 1970 and bringing together the University of Nairobi and the University of Dar es Salaam with Makerere University in Kampala, where MTSIFA is based. The 1965 class was a historic one. Alongside Gombe was a small cohort of students proficient in etching, woodcut, linocut, aquatint, and lithography. This class was the first to complete the full four years of Makerere’s new graphic art undergraduate program, founded in 1961 by Royal College of Art–trained artist Michael Adams. With its multiple textures, sinewy lines, shifts from abstraction to figuration, and plays with vertiginous perspective, Youth reflects Gombe’s notable skill. The central figure represents the apotheosis of her unlikely journey from childhood trauma to expert printmaker. However, any sense of triumph inferred by the body’s planetary perch is tempered by the anxieties inherent in the figure’s hunched pose. The sense of a precipice, or “dark hollow” beyond, speaks directly to what Gombe has recalled was “the mental uncertainty of the next path.”3Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.

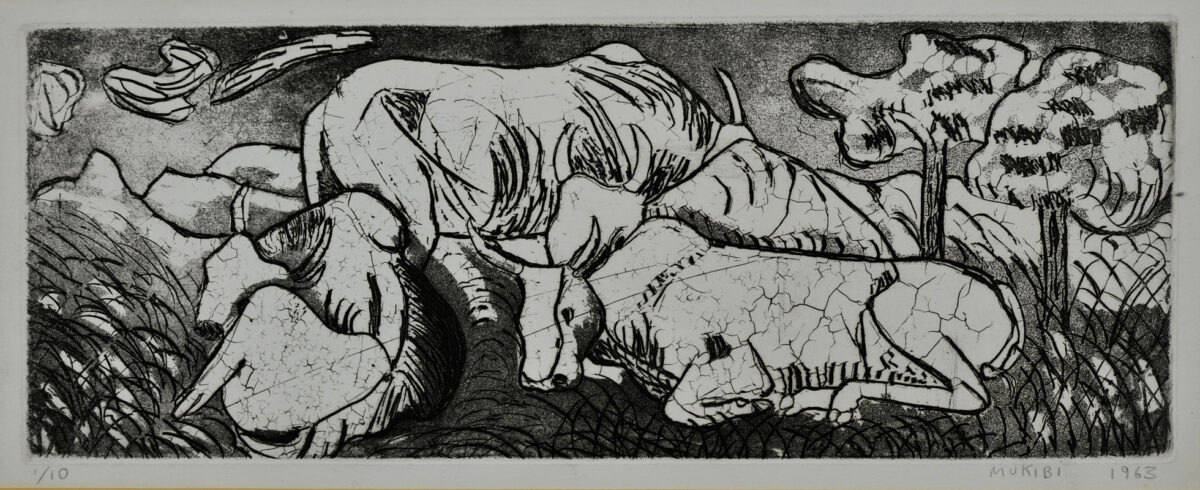

Youth, part of a trio on the theme of “Journey,” is an explicitly personal work, in which Gombe deployed her newfound printmaking skills to convey the complexities of her personal trajectory. Nonetheless, its conflicting themes and formal experimentations resonate more broadly with the school’s creative energies and tensions, providing initial insights into lesser-explored aspects of art-making at Makerere in the 1960s. Alongside prints by her classmates, such as Modest Wealth (1964; fig. 2) by Augustine Alirwana Mugalula-Mukiibi (1943–2019), Gombe’s work is a reminder that beyond the school’s better-known programs in painting and sculpture—which had, over the previous decade and a half, produced and then been led by renowned artists Sam J. Ntiro (1923–1993), Gregory Maloba (1922–2004), Elimo Njau (born 1932), Theresa Musoke (born 1944), and Francis Nnaggenda (born 1936), among others—printmaking was a burgeoning field at the heart of public creative expression in the early years of independence.

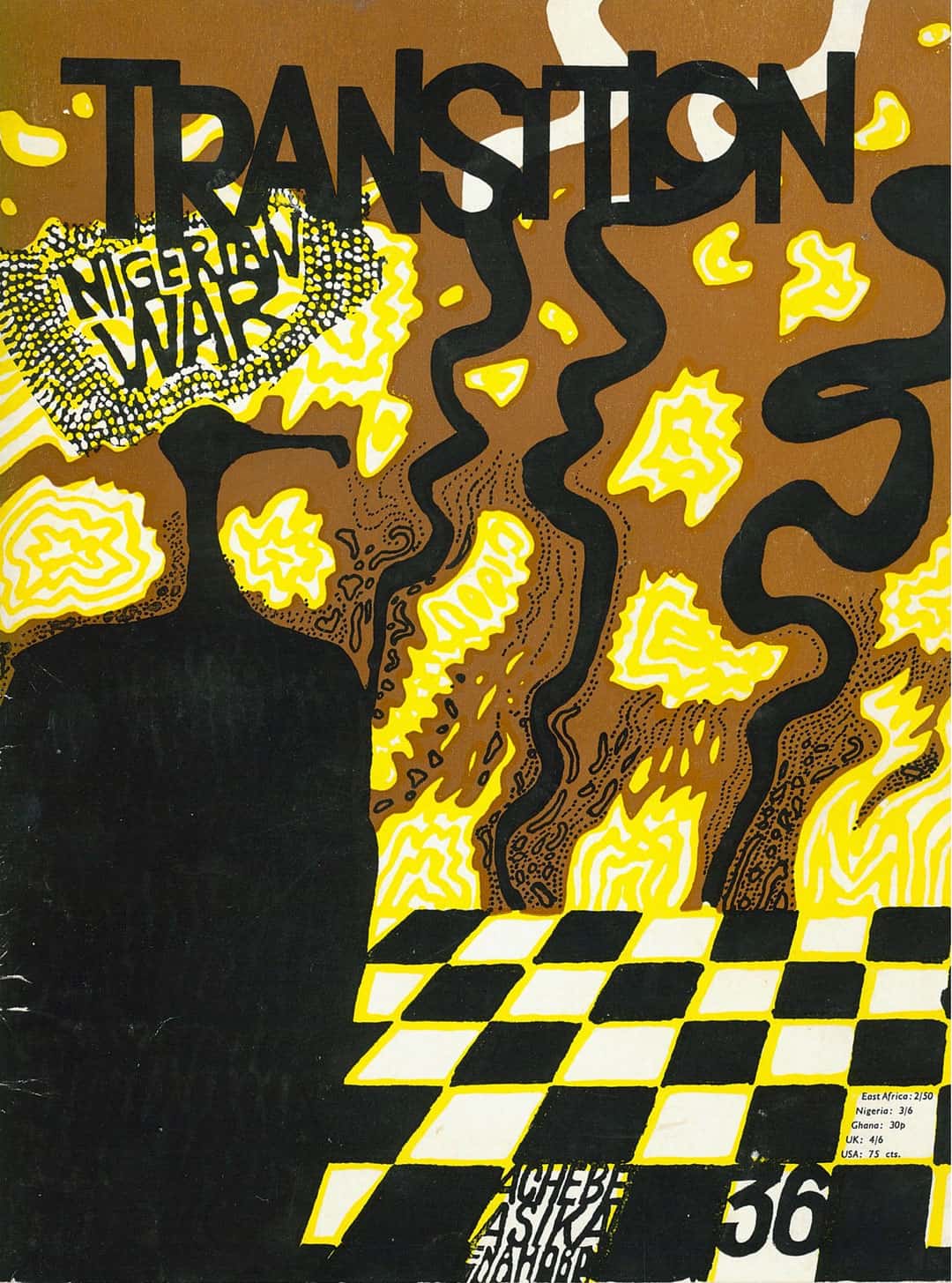

Kampala, a thriving creative city, was the locus of several young, innovative, graphic-rich publications including Roho and Transition, which were printed by Uganda Argus Ltd.4For a short overview of the contemporaneous energies in Kampala, see Anna Adima, “Literature, Music and Fashion: Cosmopolitan Kampala in the 1960s,” Global History Blog, Scottish Centre for Global History, posted October 21, 2020, https://globalhistory.org.uk/2020/10/literature-music-and-fashion-cosmopolitan-kampala-in-the-1960s/.The printmaking equipment that Adams installed at the university—a physically demanding process that he has described as “acids and fingers, hot plates and turpentine, a dangerous beginning”—enabled his students to produce imagery that fed directly into their pages.5For example, in a letter, Adams describes the physical challenges of installing a two-ton etching press in which “the flat bed shot out from two rollers,” almost mortally wounding two students who were assisting, as well as creating the aquatint box “so that it didn’t leak resin all over the room.” Michael Adams, personal communication with author, February 1, 2021. Adams, himself a painter and a printmaker, designed several iconic covers for Transition, including the 1966 cover featuring a green, red, and yellow playing card design to accompany an essay by Ali Mazrui (1933–2014) on Kwame Nkrumah, the “Leninist tzar”; the 1967 cover featuring a sardonic cartoon that accompanies an essay by Paul Theroux on Tarzan, the “first expatriate”; and an ominous design from 1968 (fig. 3) dominated by a vulture for the issue focused on the Biafran civil war.6See Ali Mazrui, “Nkrumah: The Leninist Czar,” Transition, no. 26 (1966): 9–17, https://doi.org/10.2307/2934320; and Paul Theroux, “Tarzan Is an Expatriate.” Transition, no. 32 (August–September 1967): 13–19, https://doi.org/10.2307/2934617.

At Makerere, Adams was, as Sunanda Sanyal has discussed, a provocateur unafraid of confronting a growing art world elitism.7Sunanda K. Sanyal, “‘Being Modern’: Identity Debates and Makerere’s Art School in the 1960s,” in A Companion to Modern African Art, ed. Gitti Salami and Monica Blackmun Visona (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2013), 264.This is most evident in an editorial he published in Transition in 1962 (when Gombe, Mugalula-Mukiibi, and others were in their second year), in which he denounces critics as failed artists who “stopped understanding when they stopped being creative.”8Michael Adams, “Critics: Men of Taste?” Transition, no.6/7 (October 1962): 35, https://doi.org/10.2307/2934785. In this text, he argues that the gap between high and low is relative, that both Michelangelo and Mickey Mouse constitute a “worldy experience,” and that the postcards people buy of each are, ultimately, “the same size.” Below his text, there is a small, abstract, graphic work titled Clouds, which appears like a crystalline, stratigraphic slice underscoring the idea that encounters with creative expression need not be confined to the hallowed gallery space. Adams was an inspiring teacher, one whom Gombe remembered fondly nearly sixty years later. The sentiment, it seems, was mutual. In 2021, thinking back on the class of 1965, Adams wrote “When my 4th year students left, I knew I had to follow. They had graduated me.”9Adams, personal communication with author, February 1, 2021.

As Serubiri Moses has recently discussed in reference to Gombe’s contemporary Theresa Musoke (born 1944), who won the prize for painting in 1965, the art school in the mid-1960s was both energized by Uganda’s independence in 1962 and challenged by an increasing emphasis on formalism.10Serubiri Moses, “Theresa Musoke’s Surrealist Art,” post: notes on art in a global context, December 21, 2022, https://post.moma.org/theresa-musokes-surrealist-art/.The latter had been introduced by Scottish artist Cecil Todd (1912–1986), who took over leadership of the school in 1959 and worked to shift the curriculum away from Margaret Trowell’s essentialist pedagogy promoting the belief that African artistic education should prioritize a “native” intuition free of Western influence.11For a thorough, recent evaluation of this approach, see Emma Wolukau Wanambwa, “Margaret Trowell’s School of Art. A Case Study in Colonial Subject Formation,” Art Education Research [e-journal for the Institute for Art Education, Zurich],no. 15 (2019): 1–14, https://sfkp.ch/resources/files/2019/02/AER15_Wolukau-Wanambwa_E_20190218.pdf. In its place, Todd instituted a rigorous, academic program in which students studied artworks from the Western canon, took life drawing classes, and were encouraged to gain mastery in a variety of mediums. His school sought to offer an internationalist art education, and yet it did so within a climate that the new nation state could not help but inspire.

Moses argues that Musoke rejected Todd’s formalism and turned instead to surrealist representations of nature inspired by East Africa’s rich flora and fauna.12Moses, “Theresa Musoke’s Surrealist Art.”Musoke herself took printmaking classes, and her woodcut of guinea fowl, as Moses discusses, appeared in Transition in 1963. Musoke’s evident interest in wildlife was shared by many of her contemporaries, reflecting the concern for conservation that proliferated in the wake of independence. The second issue of Roho: Journal of the Visual Arts of East Africa (1962), for example, features an excerpt from the Arusha Manifesto (1961), a foundational document in East African conservation, as well as an essay by Kenyan zoologist and Makerere professor David Wasawo that calls upon readers to recognize the urgent need for preservation, especially in an age of ever-growing tourism.13David Wasawo, “Not by Bread Alone,” Roho: Journal of the Visual Arts of East Africa, no.2 (June 1962): 24–29.Wasawo’s text is accompanied by twelve graphic depictions of animals, all of them the work of Makerere printmaking students—including Fatma Abdullah (1939-1994) , whose abstracted, writhing mass Python occupies a full half-page.

Contemporaneous artworks evidence that beyond Roho’s diminuitive illustrations, Adams’s students developed more complex works on the theme of Uganda’s wildlife, employing a range of printmaking techniques to evoke particular qualities. In figure 4, which is by a currently unknown artist, what Adams describes as a “free-wheeling line and perfect mastery of black-and-white form” conspire to convey a sinuous scene of busy, mischievous primates. The wide-eyed backward glance of the figure in the center left, in particular, has a cartoonish quality that seems to speak to a playfulness inspired by Adams’s own irreverent disregard for “sterile” and “imitative perfection.”14The artist of this print remains unknown. Along with Gombe’s and Mugalula-Mukiibi’s prints, it resides in the Argyll Collection in Scotland, brought there in the 1960s by writer Naomi Mitchison on a visit to Makerere. Research on this long-forgotten collection led to the attribution of Gombe and Mugalula-Mukiibi, but this work, along with another, depicting a heron, remain unattributed. For more on the project, see the exhibition website for Dar to Dunoon: Modern African Art from the Argyll Collection, www.dartodunoon.com. In February 2021, Michael Adams stated that he believe the print looked like the work of Berlings P. Sanka, but the signature does not confirm this, and no comparable examples of Sanka’s work have yet been uncovered. Anyone with leads regarding attribution should contact Kate Cowcher, kc90@st-andrews.ac.uk. At the same, Mugalula-Mukiibi’s work (see fig. 2) demonstrates material mastery through precision cracking of the wax on the etching plate to create a vignette that conflates the hardy bodies of Uganda’s iconic Ankole longhorn cattle with the parched earth of the harsh, desert climate in which they thrive. These works superceded Todd’s formalist insistences, pushing the material qualities of printmaking processes to elevate conservationist agendas and affront elitism—while also satisfying the appetite for new national icons.

Unlike her classmates, Gombe did not depict Ugandan fauna. She did, however, feature a large, indigenous banana leaf in the foreground of her etching, depicting it in a torn state to accentuate an atmosphere of “abundance . . . and uncertainty.”15Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.Like Mugalula-Mukiibi’s mobilization of etching’s formal qualities to infer Ankole hardiness, Gombe’s work retains a clear index of its process of production in the rendering of the map of the African continent in reverse. For the final project display, Gombe was asked to mount the actual plate she had produced, and so she chose to etch the map the correct way around for those viewing it. The resulting print, Youth, therefore represents the continent as a mirror image of itself, serving as a reminder that it was the plate itself that was the primary subject of examination. Importantly, however, the star that marks Uganda centrally on the equator remains unchanged, as the central anchor in both the etched plate and its subsequent printed manifestation. These details in Gombe’s and Mugalula-Mukiibi’s work emphasize that Makerere’s first printmaking students did not simply prioritize form over content, but rather consciously experimented with the material specificities of the former to create new representations of the latter.

In a work so deeply entrenched in Ugandan imagery, it is hard not to sense in Gombe’s anxieties about the future a broader trepidation regarding the fate of the young nation state. In 1965, tensions between Uganda’s first president, King Edward Muteesa II of Buganda, and its prime minister, Milton Obote, were rife, with the latter overthrowing the former within a year, and Idi Amin seizing power only five years later. Despite the immense difficulties and trauma of the ensuing years, both Mugalula-Mukiibi and Gombe went on to forge successful careers as artists and academics. Their printmaking training at Makerere stood them in good stead, instilling in both a lifelong attentiveness to material qualities and to Ugandan cultural iconography and heritage. Prior to his passing in 2019, Mugulalu-Mukiibi had enjoyed a long career as a master printmaker, developing, in particular, new techniques for printing on Ugandan bark cloth, which he exhibited internationally. Catherine Nankya Katonoko Gombe has similarly pursued a career steeped in the protection and celebration of historic heritages, obtaining a PhD from Kenyatta University in arts education, and publishing and teaching on ceramics, basket weaving, and bark cloth to this day. 16See, for example, Catherine Gombe, “Indigenous Pottery as Economic Empowerment in Uganda,” International Journal of Art & Design Education 1, no. 21 (February 2002): 44–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5949.00295; Catherine Gombe, “Indigenous Plaited Patterns on Ugandan mats,” International Journal of Education through Art 2, no. 3 (September 2007): 123–32, https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.3.2.123_1; and the current research project of which Gombe is co-project coordinator, “Transnational Action on Traditional Knowledge Ethos in Strategic Human Development (TATKESHD)” at University of Vienna, https://tatkeshd.univie.ac.at.

As with many of the works produced at Makerere in the 1960s, Youth was sold shortly after it was made. It was bought by Scottish writer and campaigner Naomi Mitchison on a visit to Kampala, and was sent for inclusion in the Argyll Collection, a public art initiative she had set up to provide rural, Highland communities an access to art.17For a brief overview of this history, see Kate Cowcher, “Modern African Art, from Dar es Salaam to Dunoon,” ArtUK, posted August 4 2021, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/modern-african-art-from-dar-es-salaam-to-dunoon Seeing the work again in 2021 after a long hiatus, Gombe was struck by the complexities of emotions that it evoked: “Happy and sad moments, achievements and struggles, self-assurance and uncertainty.”18Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.More than anything, however, Youth reminded her of critical childhood guidance. As she recalled, “My mother repeatedly told me, ‘Bwoba toyagala emirimu ginno, soma ennyo,’which translates as ‘If you do not like these chores, study hard.’” Academic success, she understood, would be liberating, a mantra that has guided her six-decade career as an artist and educator.

- 1I am grateful to Professor Catherine Gombe for sharing her thoughts on this work during the preparation of the exhibition Dar to Dunoon: Modern African Art from the Argyll Collection (2021). Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.

- 2This was a short-lived, multi-sited institutional configuration in operation from 1963 to 1970 and bringing together the University of Nairobi and the University of Dar es Salaam with Makerere University in Kampala, where MTSIFA is based.

- 3Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.

- 4For a short overview of the contemporaneous energies in Kampala, see Anna Adima, “Literature, Music and Fashion: Cosmopolitan Kampala in the 1960s,” Global History Blog, Scottish Centre for Global History, posted October 21, 2020, https://globalhistory.org.uk/2020/10/literature-music-and-fashion-cosmopolitan-kampala-in-the-1960s/.

- 5For example, in a letter, Adams describes the physical challenges of installing a two-ton etching press in which “the flat bed shot out from two rollers,” almost mortally wounding two students who were assisting, as well as creating the aquatint box “so that it didn’t leak resin all over the room.” Michael Adams, personal communication with author, February 1, 2021.

- 6See Ali Mazrui, “Nkrumah: The Leninist Czar,” Transition, no. 26 (1966): 9–17, https://doi.org/10.2307/2934320; and Paul Theroux, “Tarzan Is an Expatriate.” Transition, no. 32 (August–September 1967): 13–19, https://doi.org/10.2307/2934617.

- 7Sunanda K. Sanyal, “‘Being Modern’: Identity Debates and Makerere’s Art School in the 1960s,” in A Companion to Modern African Art, ed. Gitti Salami and Monica Blackmun Visona (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2013), 264.

- 8Michael Adams, “Critics: Men of Taste?” Transition, no.6/7 (October 1962): 35, https://doi.org/10.2307/2934785.

- 9Adams, personal communication with author, February 1, 2021.

- 10Serubiri Moses, “Theresa Musoke’s Surrealist Art,” post: notes on art in a global context, December 21, 2022, https://post.moma.org/theresa-musokes-surrealist-art/.

- 11For a thorough, recent evaluation of this approach, see Emma Wolukau Wanambwa, “Margaret Trowell’s School of Art. A Case Study in Colonial Subject Formation,” Art Education Research [e-journal for the Institute for Art Education, Zurich],no. 15 (2019): 1–14, https://sfkp.ch/resources/files/2019/02/AER15_Wolukau-Wanambwa_E_20190218.pdf.

- 12Moses, “Theresa Musoke’s Surrealist Art.”

- 13David Wasawo, “Not by Bread Alone,” Roho: Journal of the Visual Arts of East Africa, no.2 (June 1962): 24–29.

- 14The artist of this print remains unknown. Along with Gombe’s and Mugalula-Mukiibi’s prints, it resides in the Argyll Collection in Scotland, brought there in the 1960s by writer Naomi Mitchison on a visit to Makerere. Research on this long-forgotten collection led to the attribution of Gombe and Mugalula-Mukiibi, but this work, along with another, depicting a heron, remain unattributed. For more on the project, see the exhibition website for Dar to Dunoon: Modern African Art from the Argyll Collection, www.dartodunoon.com. In February 2021, Michael Adams stated that he believe the print looked like the work of Berlings P. Sanka, but the signature does not confirm this, and no comparable examples of Sanka’s work have yet been uncovered. Anyone with leads regarding attribution should contact Kate Cowcher, kc90@st-andrews.ac.uk.

- 15Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.

- 16See, for example, Catherine Gombe, “Indigenous Pottery as Economic Empowerment in Uganda,” International Journal of Art & Design Education 1, no. 21 (February 2002): 44–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5949.00295; Catherine Gombe, “Indigenous Plaited Patterns on Ugandan mats,” International Journal of Education through Art 2, no. 3 (September 2007): 123–32, https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.3.2.123_1; and the current research project of which Gombe is co-project coordinator, “Transnational Action on Traditional Knowledge Ethos in Strategic Human Development (TATKESHD)” at University of Vienna, https://tatkeshd.univie.ac.at.

- 17For a brief overview of this history, see Kate Cowcher, “Modern African Art, from Dar es Salaam to Dunoon,” ArtUK, posted August 4 2021, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/modern-african-art-from-dar-es-salaam-to-dunoon

- 18Gombe, personal communication with author, “Reflections on the Print—Youth,” February 2, 2021.