Theresa Musoke (born 1944) is one of Uganda’s premier artists, although the literature shows that her place alongside the masters of twentieth-century modern art in Africa is yet to be recognized. Part of the earlier generation of artists trained at the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts at Makerere University, she often goes without mention—such as in recent art criticism on Ugandan mastery.1See Dominic Muwanguzi, “Forgotten Art Masters,” The Independent, October 31, 2018, https://www.independent.co.ug/arts-forgotten-art-masters/. In this paper, I aim to provide an introduction to her art, including biographical notes and visual analysis of a selection of her paintings, prints, and sculpture. My text focuses on Musoke’s concept of the wild and also details her intellectual rebuttal of the pedagogy at the Makerere Art School during the 1960s.2When Musoke was a student, the school was known as the Makerere Art School—before it was renamed the Margaret Trowell School of Fine Arts after its founder, and later the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts. To indicate the dates of Musoke’s studies, I will refer to it as the Makerere Art School throughout this paper.

Born in Kampala, Theresa Musoke began her artistic practice in the early 1960s, and to this day, continues to make art with the tenor, range, and mastery of many African modernists of the postwar era. Her work can appear synonymous with postwar African art and has been described by scholars such as Margaret Nagawa3Margaret Nagawa, “The Challenges and Successes of Women Artists in Uganda,” in Art in Eastern Africa, ed. Marion Arnold (Dar-es-Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2008), 154. and George William Kyeyune4George William Kyeyune, “#043 Marabou Storks von Theresa Musoke,” Iwalewahaus, https://www.iwalewahaus.uni-bayreuth.de/en/collection/object-of-the-month/043/index.html. as engaging fauna, wildlife, and abstraction. Musoke’s reputation as an artist has rested on the academic training she received in various institutions in Uganda, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Arguably, the dominant theme running through literature on Ugandan and East African art more broadly is the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts and its aesthetic pedagogy.5Since its founding as a department in the 1930s, the Makerere University art school has been pedagogically guided mostly by its teachers and students, including British artists Margaret Trowell 1904–1985) and Cecil Todd (1912–1986), Kenyan artists Gregory Maloba (1922– 2004) and Elimo Njau (born 1932), Ugandan artists Francis Musangogwantamu (1923–2007), Ignatius Serulyo (born 1937), and Francis Nnaggenda (born 1936), and in the last decade, Ugandan artists Kizito Maria Kasule (born 1967) and George William Kyeyune (born 1962). However, during the 1960s, when Musoke attended the school, a strong focus was placed on anatomy and draftsmanship—and what Cecil Todd described as a realism influenced by the African novel among other developments. See Cecil Todd, “Modern Sculpture and Sculptors in East Africa,” African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music 2, no. 4 (1961): 72–76; and George William Kyeyune, “Art in Uganda in the 20th Century” (PhD thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies [University of London], 2003). It is easy to see Musoke’s excellent draftsmanship, which has been described as her art’s “sweeping brush stroke,”6“The Arts in Kenya,” Women Artists News 11, no. 1 (Winter 1986): 10. but when we step away from the academicism of her art, it is clear that her investment in and concept of the wild are more broadly inspired than merely an academic exercise would suggest. Her visual treatment of wildlife, in its illuminating and vociferous activity, recalls the interiority of postwar artists in Uganda, particularly through what I refer to as her imaginative and surreal imagery. While I do not subscribe to a singular definition of surrealism, I claim the imaginative, meditative, poetic, animist, and psychological as descriptive of Musoke’s surrealist art.

In this short paper, I challenge the claim that Musoke began working with nature and the concept of the wild during the mid-1970s in Nairobi, Kenya,7Angelo Kakade, “On the Love that Dares Exhibition: Overlapping Histories, Shared Visions,” in A Love That Dares, ed. Margaret Nagawa, exh. cat. (Kampala: AAG Gallery, 2017), 41–48; and Kyeyune, “#043 Marabou Storks von Theresa Musoke.” clarifying their presence in her aesthetic trajectory and artistic practice as early as 1963. To give a concise biography, Musoke entered the Makerere Art School in Kampala, Uganda, in 1962.8Ibid. Makerere University was widely known at the time (and in subsequent years) as the “Harvard of Africa.” Between 1962 and 1965, Musoke made waves at the art school and larger university campus by winning a painting prize, and working on a public mural commission for the old girl’s dormitory at Mary Stuart Hall, which was completed in 1953, and extensions made in 1958 that include a common room.9Martha Kazungu, “Theresa Musoke: A Lifetime Dedicated to Art in East Africa,” Contemporary And, March 8, 2019, https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/theresa-musoke-a-lifetime-dedicated-to-art-in-east-africa/. She went on to earn a diploma from the Royal College of Art in London in 1967. By 1970, Musoke was in the United States pursuing an MFA at the University of Pennsylvania. She returned to Uganda in 1972. Upon her return, she taught at the Makerere Art School for two years before leaving for Kenya, where she taught at Kenyatta University. Musoke permanently returned to Uganda in 1997. Since then, she has maintained a studio-gallery in her home, where she continues to practice painting, drawing, and printmaking.

During World War II (1939–45)

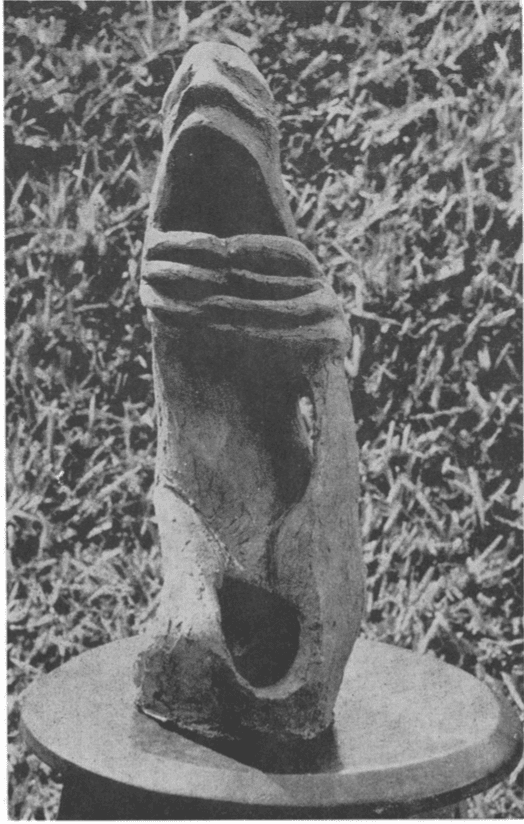

The prevailing dark mood in East African art emerged in the 1940s within the context of World War II. For example, several works made in 1941 by Gregory Maloba (1922–2007), a pioneer modernist in East Africa, clearly reflect the mood of the time.10For more, see Serubiri Moses, “Death and the Stone Age: Ugandan Art Institutions (1941–1967),” in How Institutions Think: Between Contemporary Art and Curatorial Discourse, ed. Paul O’Neill, Lucy Steeds, and Mick Wilson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017): 56–65. This mood lent itself to folklore. Maloba used the myth of walumbe (death) in his 1941 wood sculpture Death, and similar references to mythology can be traced in the work of many Makerere artists. The emergent Makerere style is evidenced in the work of Maloba and his contemporaries—including Sam James Ntiro (1923–1993), whose 1956 oil painting Men Taking Banana Beer to Bride at Night is in MoMA’s collection—who are considered the first group of Makerere Art School artists. The emergence of the Makerere style was no doubt inspired by the teachings of Margaret Trowell and her pedagogical focus on folkloric myth. However, during and after World War II, artists working in the Makerere style generally chose somber, mournful, or terror-filled myths as sources for their imagery.

Early Years at the Makerere Art School

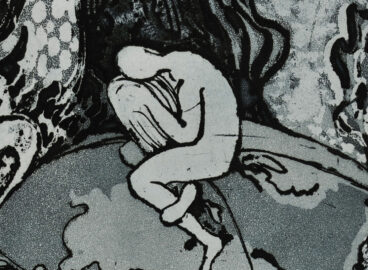

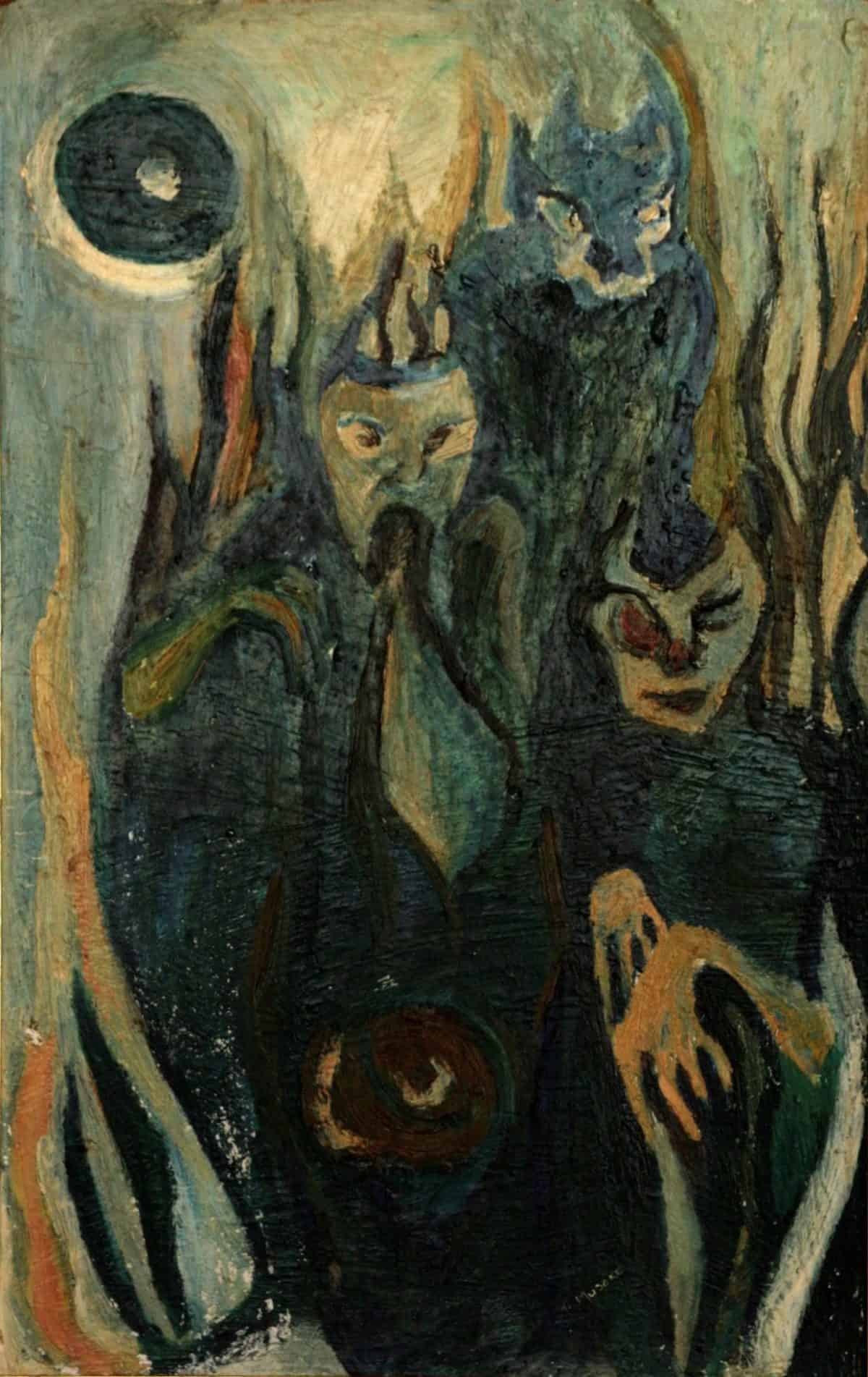

Theresa Musoke is no exception to the prevailing dark mood expressed in the postwar by artists in East Africa. Her earliest works, such as Anguish (1964; fig. 1) and Cat Ghosts (1962; fig. 2) reflect this somber state of mind. Although Musoke’s work in the 1960s was created in a moment of optimism, and indeed of transition, her much-discussed turn to animal imagery is consistent with the deeply meditative. For instance, her visions of birds and the wild are not “realistic” but rather taken from the imagination. In this sense, her concept of the wild is complex. Such is the case with Guinea Fowls (1963; fig. 3), which was featured in 1963 in Transition magazine. The three birds in this image all face different directions and move across the entire plane of the woodcut. Musoke’s use of space creates the impression that there is no horizon line. Her tendency to break the horizon and create compositions in which much activity takes place but isn’t fixed by a foreground and background, or sight lines, has persisted throughout her career.

In contrast to the dominant discourse on twentieth-century art in Africa, in which artists are measured by their proximity to “modern life,” artists like Musoke have produced a different picture of their experiences. If the urban is absent in Musoke’s art, and further, if her concept of the “wild” tends to be misplaced by Ugandan historians in a lineage of British or American Romanticism and its view of the sublime,11Ibid. then her early 1960s Cat Ghosts (fig. 2) suggests that her concept of the wild has an affinity with a certain temperament. “Cat Ghosts” translates as emiyaayu in Luganda, and is used in this context to mean roaming or hostile spirits. Effectively, Musoke’s works confront the postwar anxieties of East Africa as it was coming out from under the clutches of British colonial rule.

The atmosphere at the art school had changed by the time Musoke was admitted as a student, when Maloba and other former students were already teaching there. She encountered a changing department, one that reflected the optimism of Ugandan independence from Britain in 1962. One may ask how the zeitgeist of transition influenced her art, and yet by her second year at the Makerere Art School, she was working with nature. In addition to Guinea Fowls, she produced Cat Ghosts in the style promoted by the art school at that time, that is, the style of artists such as Gregory Maloba, whose innovative aesthetic centered highly emotive subjects such as death and horror. The Makerere Art School, which had been in existence for almost two decades in the early 1960s, emphasized the use of myth, and these artists pushed the aesthetic further by creating aesthetic innovations that foreground the dark atmosphere of the postwar era in East Africa. While Musoke’s Guinea Fowls may not give an accurate depiction of these emotive aesthetics or the somber state of mind of the era, her later surrealist sculpture Anguish (1964; fig. 1), which was featured in 1964 in Transition magazine, does.12Theresa Musoke, “Anguish,” Transition 15 (1964): 49. The sculpture depicts a figure whose body is visibly contorted, its face looking up into the sky and its hands loosely folded together. Its two legs are either rested or kneeling, and the work bears several hollow spaces or voids that cast shadows in sharp light, evoking the traumatic dimensions of the era. Musoke’s turn to nature in 1963 shows her resolution in establishing her own path.

After Makerere

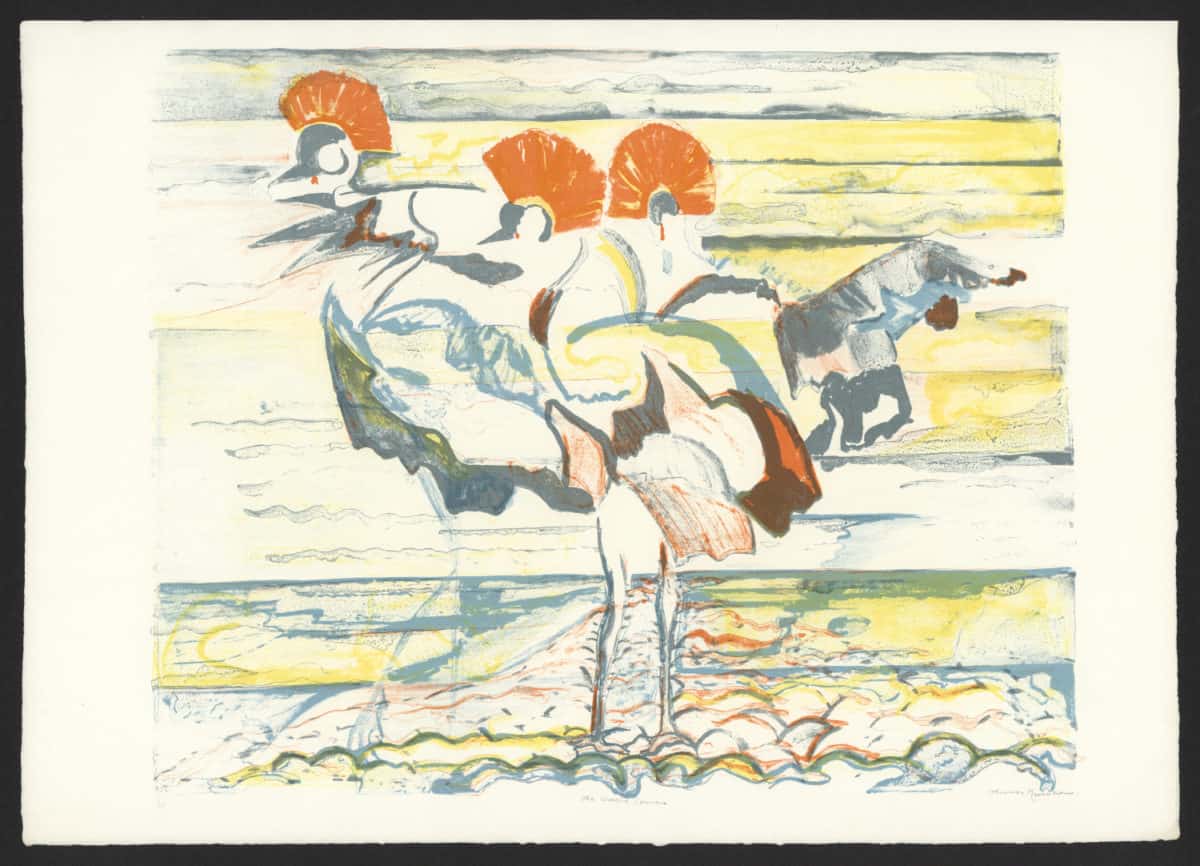

When Musoke was at the Royal College of Art in 1967, she continued her engagement with nature and natural imagery. In The Crested Cranes, a startling beautiful print from 1967 (fig. 4), she depicted the national bird of Uganda. In this lithographic print on paper, her use of color is extravagant. The composition includes a trio of crested cranes, all of which are dancing or flapping their wings. The background is serene, depicting what could be either a clear sky or a calm sea marked by horizontal lines that extend across the plane in a way that appears more forceful. The marshland on which the cranes dance has a more rugged terrain. This work can be contextualized in the history of Ugandan art, which includes oil paintings of crested cranes by Harry Johnson, founder of the Uganda Museum (a Greek temple on Mengo hill), and more recently, works such as a large watercolor drawing of crested cranes by Taga Nuwagaba (born 1968). These works signal to the viewer that Musoke cannot be separated from the social and political history of Uganda, and that as an artist, she understands the visual iconography that has produced Uganda’s history and narrative. If, as art historian Angelo Kakande argues, Musoke did not depict politics in her art,13Kakade, “On the Love that Dares Exhibition,” 41–48. and as art historian Margaret Nagawa states, she isn’t interested in “social issues,”14Nagawa, “The Challenges and Successes of Women Artists in Uganda,” 154. perhaps this artwork shows us that Musoke embraces the “national” as a paradigm for art-making. Some of the other prints she produced in 1967 also incorporate birds—for example, Feed (1967; fig. 5), which depicts what I view as a reed bunting with thick brown plumage whose mouth is wide open as it reaches out for a circular piece of food. Reed buntings occur year-round in the United Kingdom and would have been a common sight when Musoke studied there.

Indeed, Musoke does not easily fit into neat boxes of social realism that depict feminist art or the incumbent postcolonial regimes. And thus, anyone turning to her art in hopes of finding a clear illustration of either postcolonial or anti-colonial political struggle, or of women’s experience and feminism will be disappointed. I believe that Musoke began to challenge realism fairly early on as a student at the Makerere Art School when, in 1962–63, she enrolled in anatomy classes. In this setting, she favored the peculiar “beautiful ugly”15I use this term to refer to the particular orientation toward “horror” in the artwork of Ugandan artists in the postwar era. aesthetic of Gregory Maloba and Ignatius Serulyo (1937–2018), and evolved from this position to inject her own personality into her art. This includes her turn to nature as a source. It also includes her opposition to a particular brand of formalist aesthetics under the baton of Scottish artist Cecil Todd (1912–1986), who was dean of the Makerere Art School in the 1960s when Musoke was a student there.

1980s to the Present

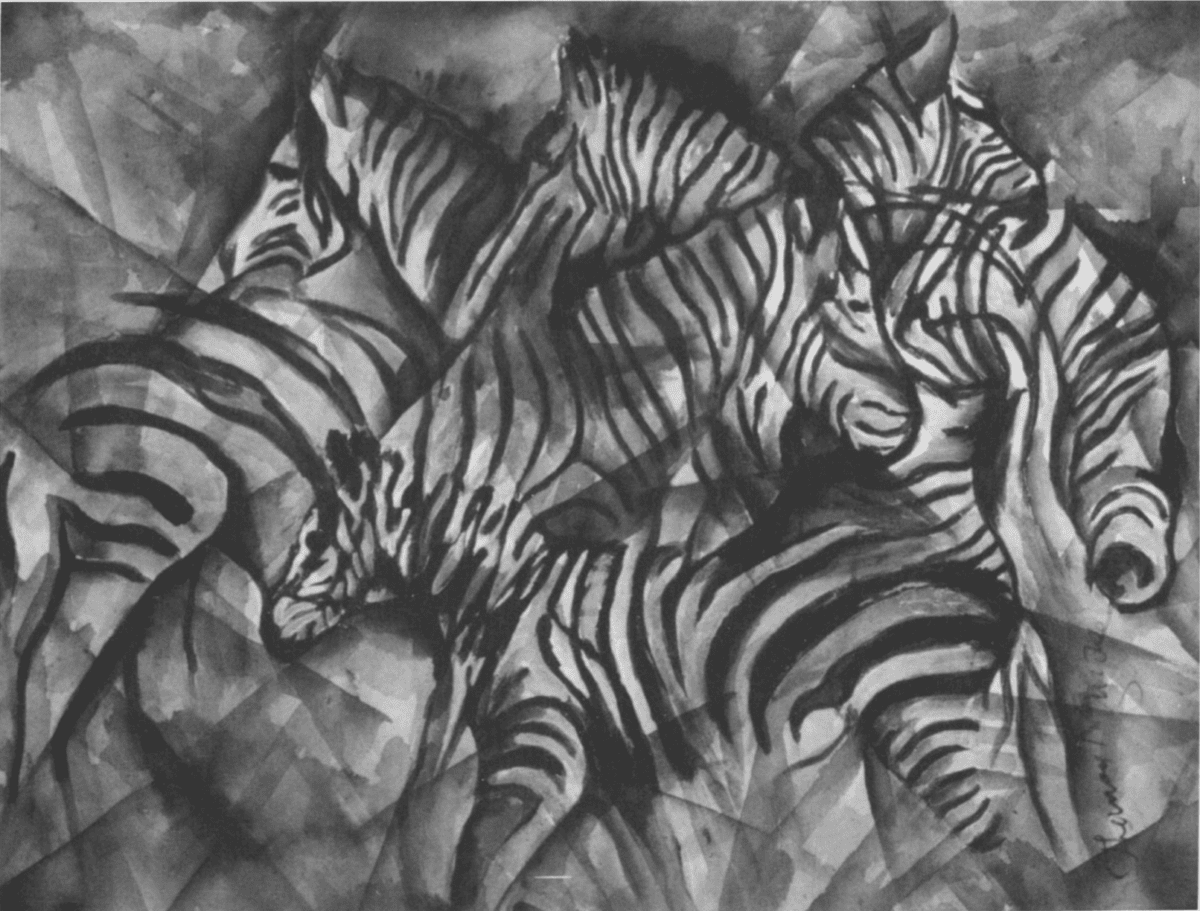

Musoke’s art has been included in a range of important exhibitions from the 1980s onward,16These include Sanaa: Contemporary Art in East Africa, Commonwealth Institute, London, 1984; Armory Pre-Selection, Parliament House, London, 1984; the first Johannesburg Biennale, 1995; various exhibitions at Gallery Watatu, Nairobi, c. 1990s; Theresa Musoke—Legendary Artist of Uganda, Nairobi Gallery, 2017; A Love That Dares, Afriart Gallery (AAG), Kampala, 2017; Mwili, Akili na Roho—East African Figurative Painting of the 1970s–90s as part of Michael Armitage. Paradise Edict, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2021; and A Retrospective of Three Artists: Theresa Musoke, Thabita wa Thuku, Yony Waite, Circle Art Gallery, Nairobi, 2022. and questionably positioned within a modernist and primitivist trajectory.17See Kakande, “On the Love That Dares Exhibition,” 41–48. Her work of the 1980s incorporates dense imagery suspended in space. In this period, Musoke’s visual language matured to what has become her recognizable style. Her paintings from 1982 to 1986 reveal an almost complete revolt against the notion of a stable horizon line, and in Zebras (1983; fig. 6), she pushed her concept of space even further by depicting the animal figures suspended in midair. Her output from the 2000s onward has been similarly prolific.

In closing, Musoke is an artist who has carried out active intellectual opposition to dominant aesthetic ideologies, such as to the particular human anatomical pedagogies of the Makerere Art School during Todd’s tenure (although she would occasionally return to portraiture in the early 1980s and after).18Betty LaDuke, “East African Painter Theresa Musoke: Uhuru or Freedom,” Art Education 42, no. 6 (1989): 16–24. This view might be contested by art historian Kyeyune, who wrote that her rigorous formal training in subjects such as anatomy is a dominant force in her art.19Kyeyune, “#043 Marabou Storks von Theresa Musoke.” Art historian Nagawa has argued that this kind of intellectual opposition could be contextualized within the “artistic, social, and intellectual issues” that have preoccupied Ugandan women artists, who have forged largely independent careers within a patriarchal field.20Nagawa, “The Challenges and Successes of Women Artists in Uganda,” 154. Lastly, Musoke’s surreal imagery continues to be sweeping and densely psychological. Her work may parallel twentieth-century post–Independence Uganda in its breadth, and it shows an artist who has innovated her own style and aesthetic sensibility. With this innovation in mind, Musoke’s influence on East African artists, particularly with respect to the surreal landscape, is towering.

- 1See Dominic Muwanguzi, “Forgotten Art Masters,” The Independent, October 31, 2018, https://www.independent.co.ug/arts-forgotten-art-masters/.

- 2When Musoke was a student, the school was known as the Makerere Art School—before it was renamed the Margaret Trowell School of Fine Arts after its founder, and later the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts. To indicate the dates of Musoke’s studies, I will refer to it as the Makerere Art School throughout this paper.

- 3Margaret Nagawa, “The Challenges and Successes of Women Artists in Uganda,” in Art in Eastern Africa, ed. Marion Arnold (Dar-es-Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2008), 154.

- 4George William Kyeyune, “#043 Marabou Storks von Theresa Musoke,” Iwalewahaus, https://www.iwalewahaus.uni-bayreuth.de/en/collection/object-of-the-month/043/index.html.

- 5Since its founding as a department in the 1930s, the Makerere University art school has been pedagogically guided mostly by its teachers and students, including British artists Margaret Trowell 1904–1985) and Cecil Todd (1912–1986), Kenyan artists Gregory Maloba (1922– 2004) and Elimo Njau (born 1932), Ugandan artists Francis Musangogwantamu (1923–2007), Ignatius Serulyo (born 1937), and Francis Nnaggenda (born 1936), and in the last decade, Ugandan artists Kizito Maria Kasule (born 1967) and George William Kyeyune (born 1962). However, during the 1960s, when Musoke attended the school, a strong focus was placed on anatomy and draftsmanship—and what Cecil Todd described as a realism influenced by the African novel among other developments. See Cecil Todd, “Modern Sculpture and Sculptors in East Africa,” African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music 2, no. 4 (1961): 72–76; and George William Kyeyune, “Art in Uganda in the 20th Century” (PhD thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies [University of London], 2003).

- 6“The Arts in Kenya,” Women Artists News 11, no. 1 (Winter 1986): 10.

- 7Angelo Kakade, “On the Love that Dares Exhibition: Overlapping Histories, Shared Visions,” in A Love That Dares, ed. Margaret Nagawa, exh. cat. (Kampala: AAG Gallery, 2017), 41–48; and Kyeyune, “#043 Marabou Storks von Theresa Musoke.”

- 8Ibid.

- 9Martha Kazungu, “Theresa Musoke: A Lifetime Dedicated to Art in East Africa,” Contemporary And, March 8, 2019, https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/theresa-musoke-a-lifetime-dedicated-to-art-in-east-africa/.

- 10For more, see Serubiri Moses, “Death and the Stone Age: Ugandan Art Institutions (1941–1967),” in How Institutions Think: Between Contemporary Art and Curatorial Discourse, ed. Paul O’Neill, Lucy Steeds, and Mick Wilson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017): 56–65.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Theresa Musoke, “Anguish,” Transition 15 (1964): 49.

- 13Kakade, “On the Love that Dares Exhibition,” 41–48.

- 14Nagawa, “The Challenges and Successes of Women Artists in Uganda,” 154.

- 15I use this term to refer to the particular orientation toward “horror” in the artwork of Ugandan artists in the postwar era.

- 16These include Sanaa: Contemporary Art in East Africa, Commonwealth Institute, London, 1984; Armory Pre-Selection, Parliament House, London, 1984; the first Johannesburg Biennale, 1995; various exhibitions at Gallery Watatu, Nairobi, c. 1990s; Theresa Musoke—Legendary Artist of Uganda, Nairobi Gallery, 2017; A Love That Dares, Afriart Gallery (AAG), Kampala, 2017; Mwili, Akili na Roho—East African Figurative Painting of the 1970s–90s as part of Michael Armitage. Paradise Edict, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2021; and A Retrospective of Three Artists: Theresa Musoke, Thabita wa Thuku, Yony Waite, Circle Art Gallery, Nairobi, 2022.

- 17See Kakande, “On the Love That Dares Exhibition,” 41–48.

- 18Betty LaDuke, “East African Painter Theresa Musoke: Uhuru or Freedom,” Art Education 42, no. 6 (1989): 16–24.

- 19Kyeyune, “#043 Marabou Storks von Theresa Musoke.”

- 20Nagawa, “The Challenges and Successes of Women Artists in Uganda,” 154.