This text considers the work of Vera Pagava, a Georgian artist who lived in exile in Paris, as an amalgamation of modernist and Georgian art historic references. Following Pagava’s life story from Tbilisi, where she was born, to Germany and later Paris, where she settled with her family in 1923 and lived until her death in 1988, this essay introduces her work in relation to that of various other Georgian artists, simultaneously tracing her path from figuration to abstraction.

Vera Pagava was born in 1907 in Tbilisi, Georgia. In 1919, she and her family left Georgia when her father, Georges Pagava, fell ill. Although the Pagava family intended to return, they soon realized that they would have to wait to do so, for Georgia was going through turbulent times, culminating in the 1924 August Uprising, an unsuccessful insurrection against Soviet rule.1Georgia was a Democratic Republic between 1918 and 1921, when it was annexed by the Red Army. In 1923, after living in Germany for several years, Pagava and her family moved to France, where they joined the Georgian émigré community settled in Montrouge. Between 1932 and 1939, Pagava studied fine art at the Académie Ranson in Paris with Roger Bissière (1886–1964) and Nicolas Wacker (1897–1987). She became friends with a group of artists in Paris, most of whom were also émigrés, including Portuguese painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992) and Hungarian painter Árpád Szenes (1897–1985).

In order to understand Pagava’s position as an artist, it is important to consider her biography not only within Paris and the larger international context, but also within twentieth-century Georgian history. The political situation in her native country in the 1920s had left her not only an émigré, but also an artist in exile.

Apart from her Georgian community in France, Pagava had a close relationship with her uncle Giorgi Naneishvili, who managed to return to Tbilisi (where in 1937, he was arrested and assassinated by the Soviets). Nonetheless, through him, she met other Georgian artists in Paris, including Ketevan Magalashvili (1894–1973), David Kakabadze (1889–1952), and Lado Gudiashvili (1896–1980), among others. Even though Pagava stayed in France until her death, she and her life companion Vano Enoukidze (1907–1979), who was also an artist and exile, and her family members never chose to become French citizens.

Not being interested in securing French citizenship was something Pagava shared with her friend and gallerist Tamara Tarassachvili who, in 1972, opened Galerie Darial with an exhibition of Pagava’s paintings.2Vera Pagava, Peintures, Galerie Darial, Paris, May 3–June 17, 1972. Not only a vibrant place in the context of Paris, Galerie Darial was also the first commercial gallery in the history of Georgian galleries. Its name was derived from the Darial Gorge, a river gorge in the Caucasus on the border between Russia and Georgia. Darial Gorge and the river Tergi located within it were popular subjects among late nineteenth-century Georgian and Russian poets and writers, including Ilia Chavchavadze (1837–1907) and Akaki Tsereteli (1840–1915). Notably, Darial Gorge is immortalized in “Demon” (1839), a masterpiece of European Romantic poetry by Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841). The Tergi and Darial Gorge would become symbols of resistance, independence, and the dissemination of knowledge in late nineteenth-century Georgian culture.

Apart from its name, the gallery also had a strong Georgian identity in terms of its graphic design. Tarassachvili chose to use the Georgian letter D (დ) as its main visual identity (fig. 1). At the time, given Georgia was hardly recognized as a culture independent from Russia, this seemingly subtle gesture was in fact a bold political statement.

In 1944, long before Darial represented Pagava, gallerist Jeanne Bucher introduced the artist’s work to Parisian audiences in a two-person exhibition with Dora Maar (1907–1997).3Quelques peintures de Dora Maar et Vera Pagava, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, June 13–30, 1944. From that point onward, Pagava’s work continued to be exhibited in France as well as throughout Europe and the United States—including in the 33rd Venice Biennale, held in 1966, in a group exhibition curated by Jacques Lassaigne, in which Pagava represented France. In Venice, Pagava’s abstract watercolor series from 1962–63 was showcased in the French Pavilion.

Parallel to Pagava’s artistic development in France, Georgian art history was evolving, shifting from a short-lived modernist period toward Socialist Realism. Especially in the 1930s, artists, poets, and visionaries on the other side of the Iron Curtain were either brutally executed or pushed to adapt to Soviet censorship. Artists in Georgia during this time, such as Niko Pirosmanashvili (Pirosmani, 1862–1918), found inspiration in practices allowed by the regime—for example, in works in the style of nineteenth-century Tbilisian portraiture—considered the first wave of independent Georgian portraiture, and Christian Orthodox wall painting of the Middle Ages.

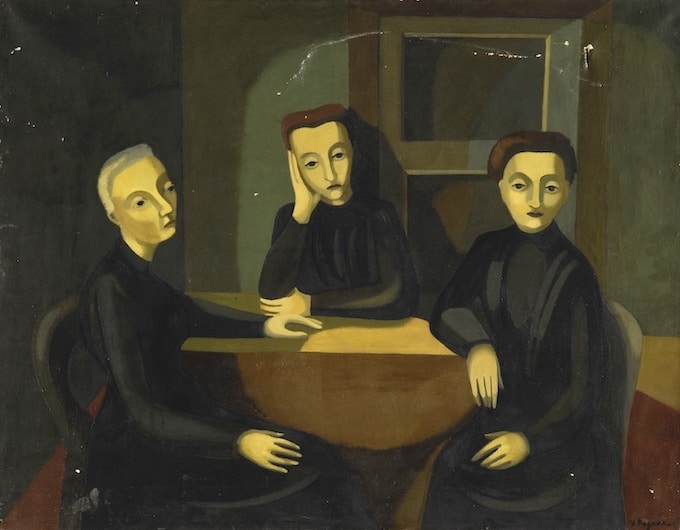

In Pagava’s earlier works, in particular, one can trace influences of Georgian painting tradition. For example, Les Magnan (1947; fig. 3), which depicts three ladies dressed in black gathered around a table in a dim interior, is reminiscent of Tbilisian Portrait, Portrait of Andronikashvili (fig. 4) as well as early portraits by Ketevan Magalashvili (1894–1973; figs. 5, 6).4Ketevan Magalashvili was a famous portrait painter and among the pioneering Georgian women artists working in this genre. She studied painting in Tbilisi with acclaimed Georgian artist Mose Toidze (1871–1953) and then continued her studies in Moscow under painters Konstantin Korovin (1861–1939) and Nikolay Kasatkin (1859–1930). Between 1923 and 1926, she studied art at the Académie Colarossi in Paris. She worked at the Georgian National Gallery, which was newly established by her life partner, painter Dimitri Shevardnadze (1885–1937). Together, she and Shevardnadze were influential in Georgian cultural circles. Magalashvili is known for her portraits of the cultural workers and other cultural actants in Georgia at this time. Her legacy is also important in terms of its historical and documentary dimensions.

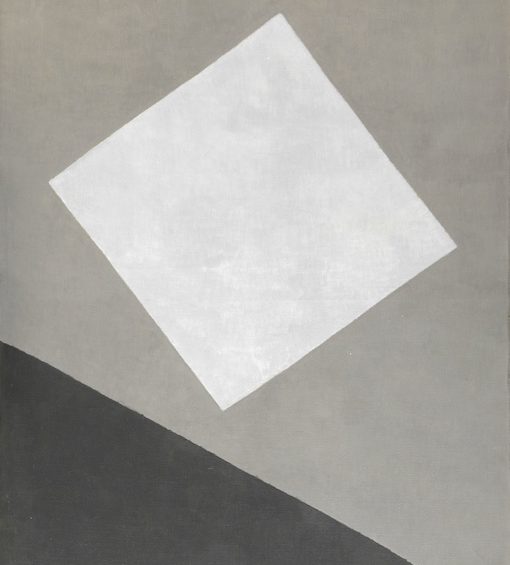

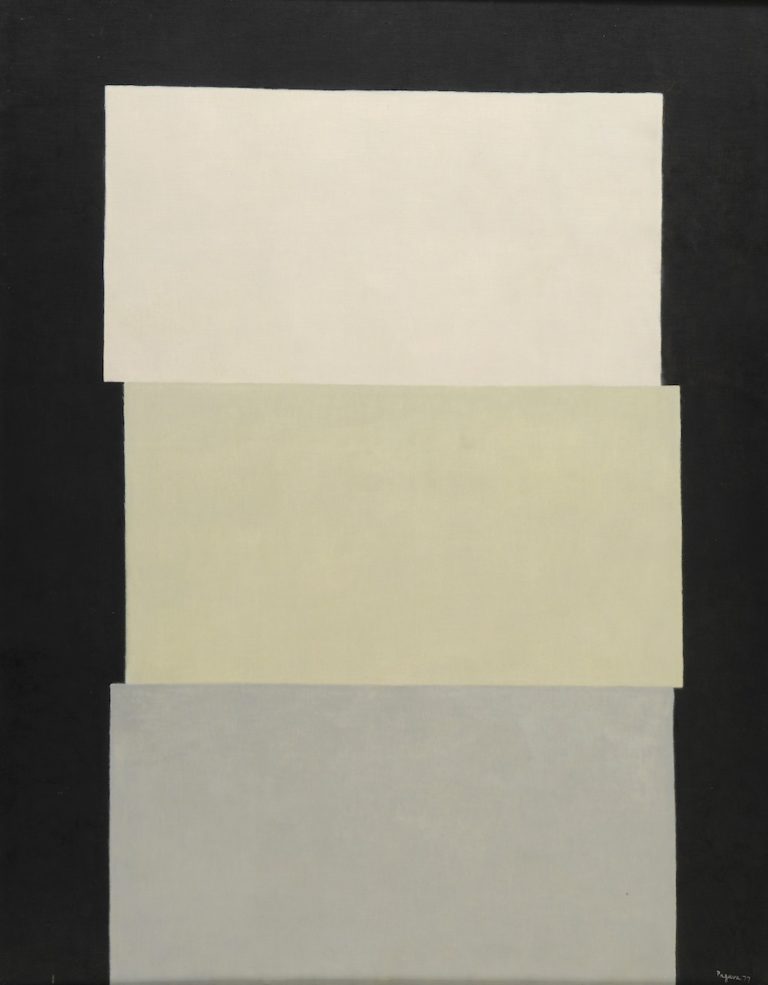

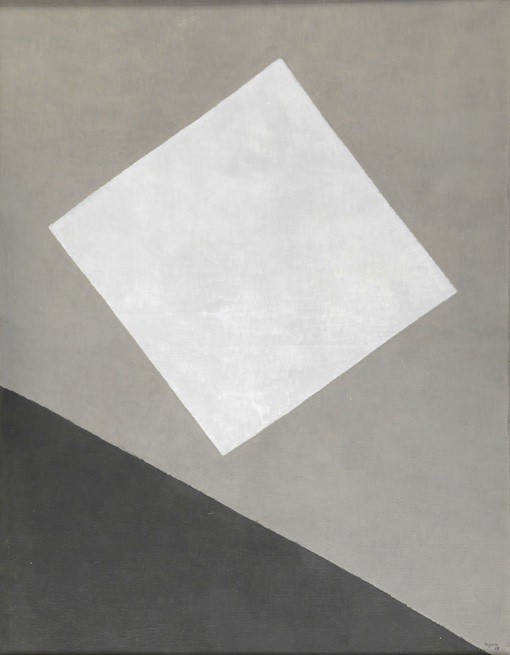

The women in the portraits by Magalashvili also wear black, and they too are seated—and look out at the viewer. Their dark clothing contrasts with the lightness of their skin, highlighting their faces and hands. In all four portraits, the subjects’ postures and hand positions resemble one another. Curiously, the hands, in particular, evoke the hands in a much older portrait—an iconic twelfth-century portrait of the female King Tamar (fig. 7). Here, the shape of the king’s hand is noteworthy. Again, the light skin color and delicacy of the fingers are in contrast to the decorative elements of the subject’s clothing, and the rough, dark form of the object she holds. The geometrical figure of a square also occurs in all of the above-mentioned works: in the form of a window (fig. 3), a framed painting (fig. 5), a chairback (fig. 6), and an architectural model (fig. 7). The color black is dominant and serves as a background for much lighter colors—as well as frames the face and hands of those depicted.

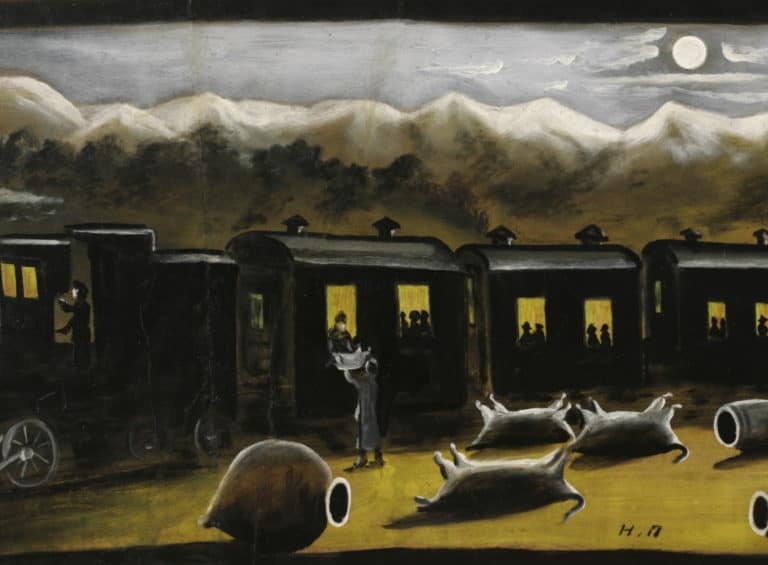

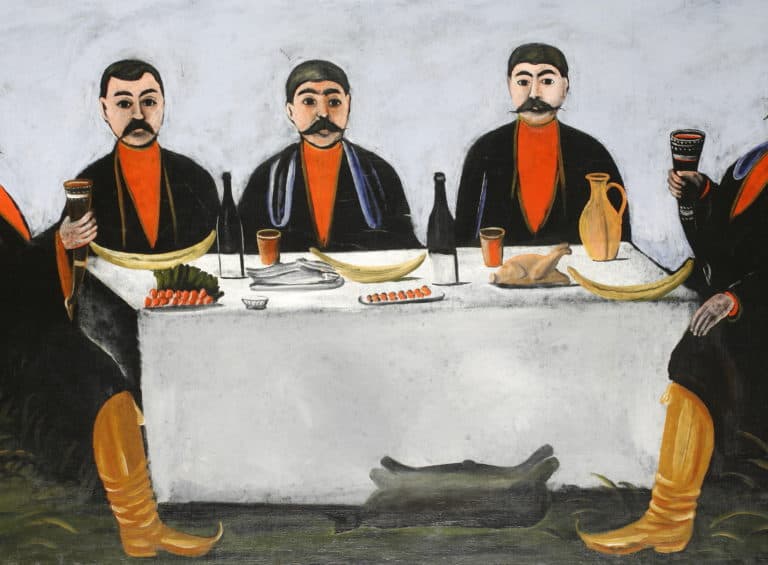

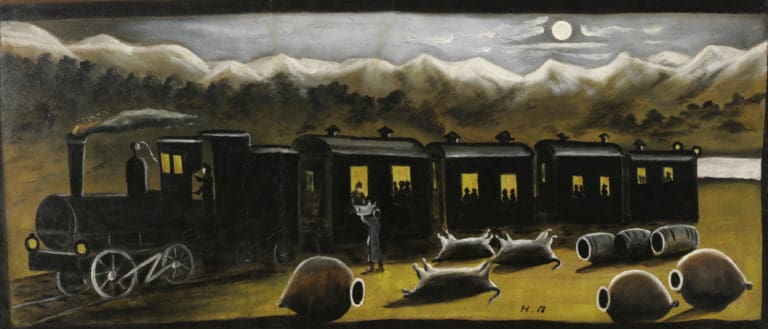

In discussing the use of black in Georgian art, one cannot bypass the legacy of Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918), a self-taught artist who applied his paint directly to black oilcloth. Indeed black serves as a backdrop in most of his works. Recognized mostly posthumously, Pirosmani had an immense influence on the generations of artists that followed him, and Vera Pagava was no exception. It is known through her archive of personal belongings that she kept a Pirosmani catalogue in her studio, as well as reproductions from the Pirosmani exhibition held in 1969 at the Musée des arts décoratifs, the Louvre.5Niko Pirosmanachvili, 1862–1918, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée des arts décoratifs, 1969). Pirosmani’s influence can be felt throughout Pagava’s oeuvre, much of which uses his work as a point of departure. This is especially the case in Pagava’s earlier figurative works, but traces of Pirosmani’s luminous work can also be detected in the balance of heavenly light and darkness in her later abstract paintings.

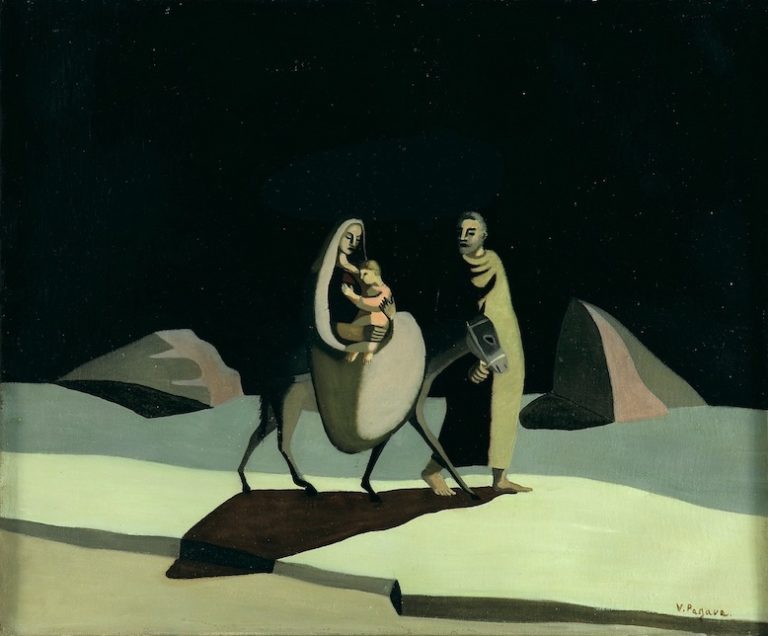

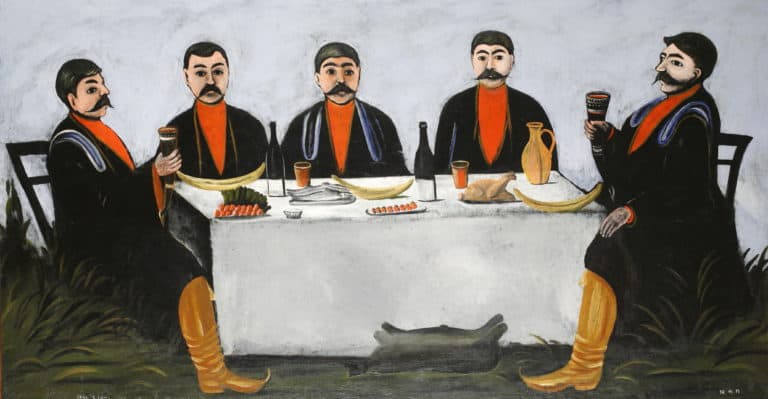

Pagava’s later works, such as The Flight into Egypt (La Fuite en Egypte, 1944; fig. 8), Théatre Hebertot (1947; fig. 10), and Still Life with Bread, Slices of Melons, Glass (1954; fig. 12) evoke works by Pirosmani in subject matter, as well as in core technical aspects (see, for example, figs. 9, 11, 13). What is salient in both artists’ work is the balance between light and dark, the contrast created between black and yellow tones, and the almost autonomous quality of illumination. In examining the rendering of Georgian bread on the table in Pirosmani’s painting The Feast of Five Noblemen (1906; fig. 13) and of the melons on the table in Pagava’s Still Life with Bread, Slices of Melons, Glass (fig. 12), one sees the source of inspiration for what is a leitmotif in Pagava’s paintings. The recurring image of a half-moon-shaped melon in Pagava’s still lifes calls to mind Pirosmani’s masterful depictions of a supra (Georgian traditional feast)—and his focus on the objects on the table, rather than on the figures surrounding them. The transcendental nature of objects and subjects is yet another interest the two artists shared.

Throughout World War II (1939–45), particularly after the German invasion and occupation of France, Pagava explored biblical themes, addressing the difficult historical moment through religious subject matter. The absence of the figure in this series addressing the war’s brutality is emphasized in the archetypal nature of the narrative suggested by the objects depicted. The stark rendering of these images serves to represent the un-representable, and to evoke the biblical proportions of the tragedy of the times.

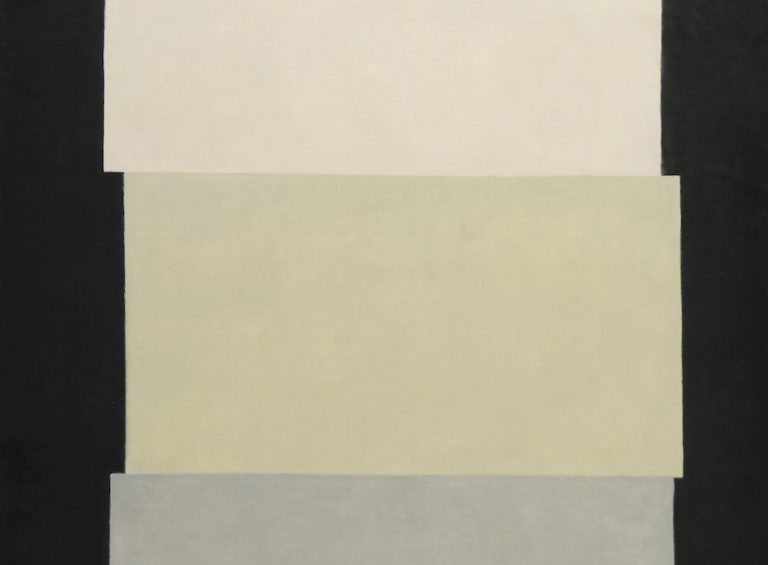

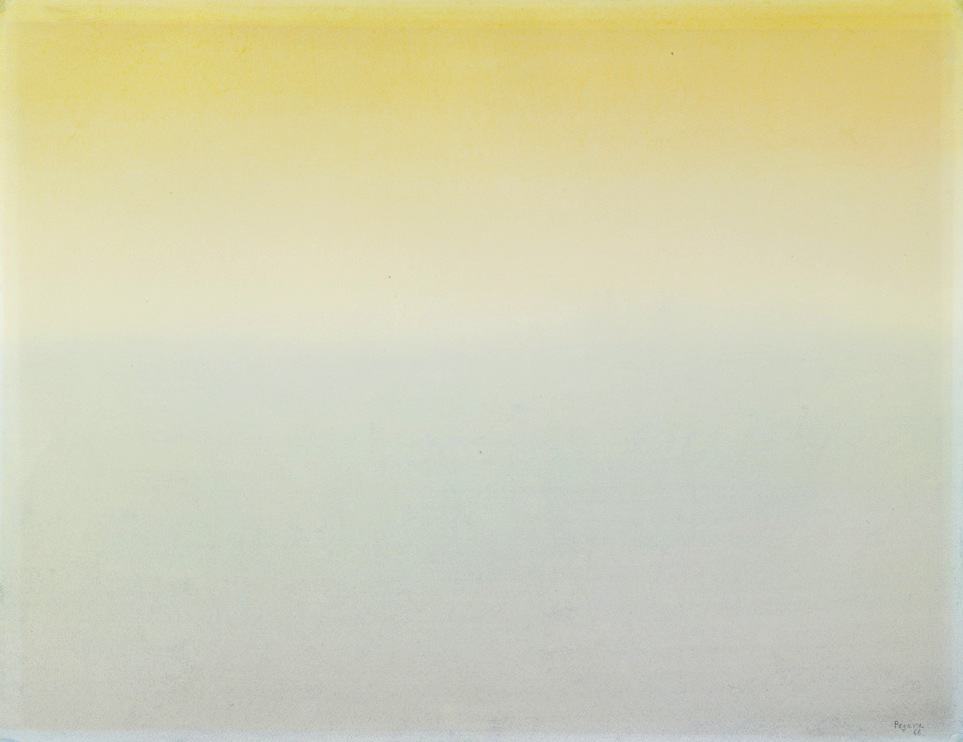

By the end of the 1950s, Pagava’s work had grown even more abstract. In this transitional period, the artist undertook a series of architectural landscapes in which she reduced buildings to almost pure geometric form, engaging the viewer in an interplay of lines and color (figs. 16, 17).

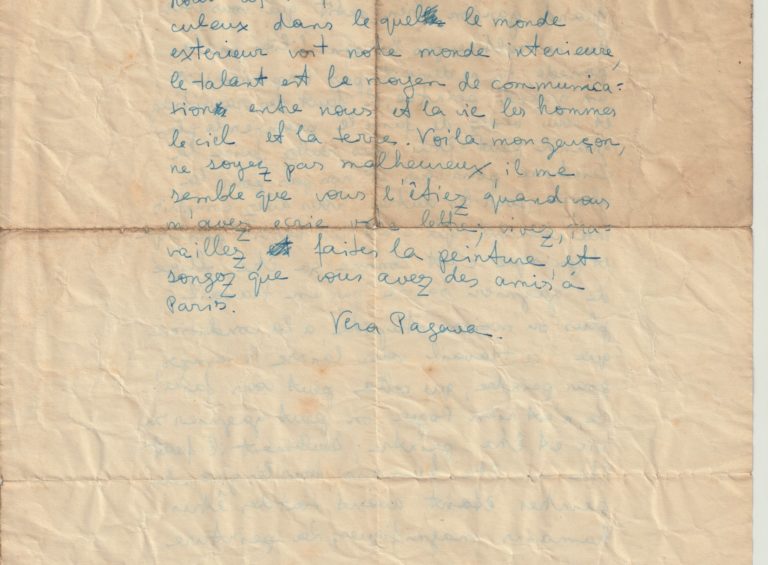

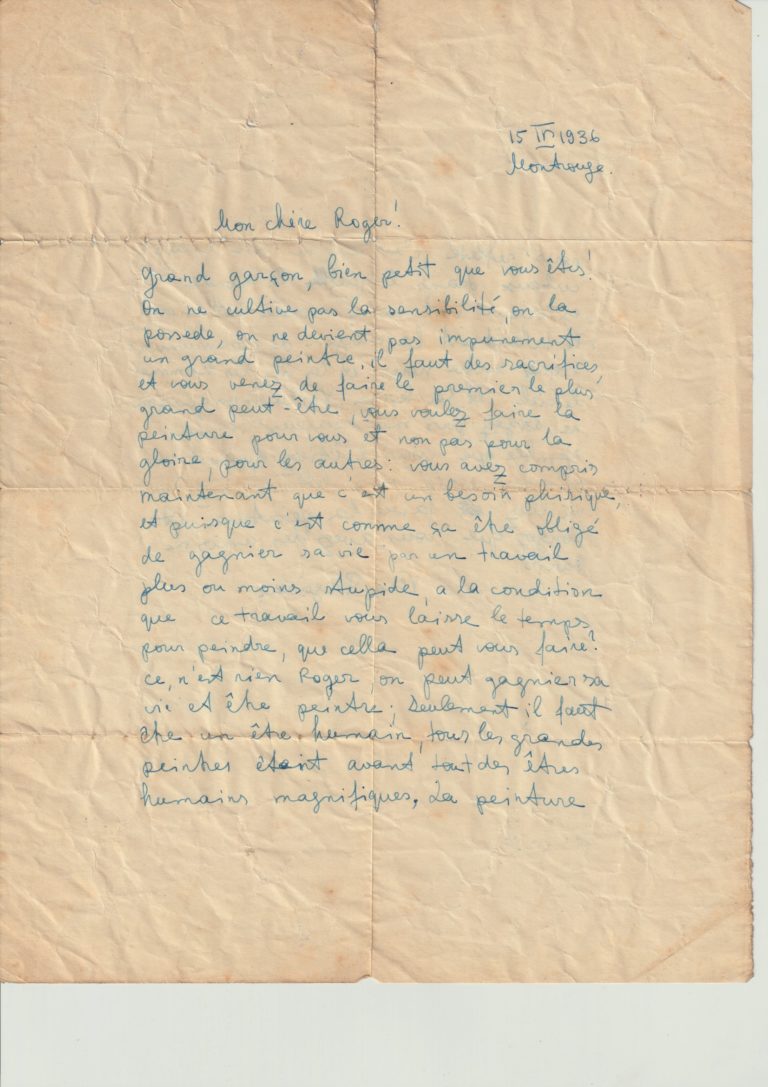

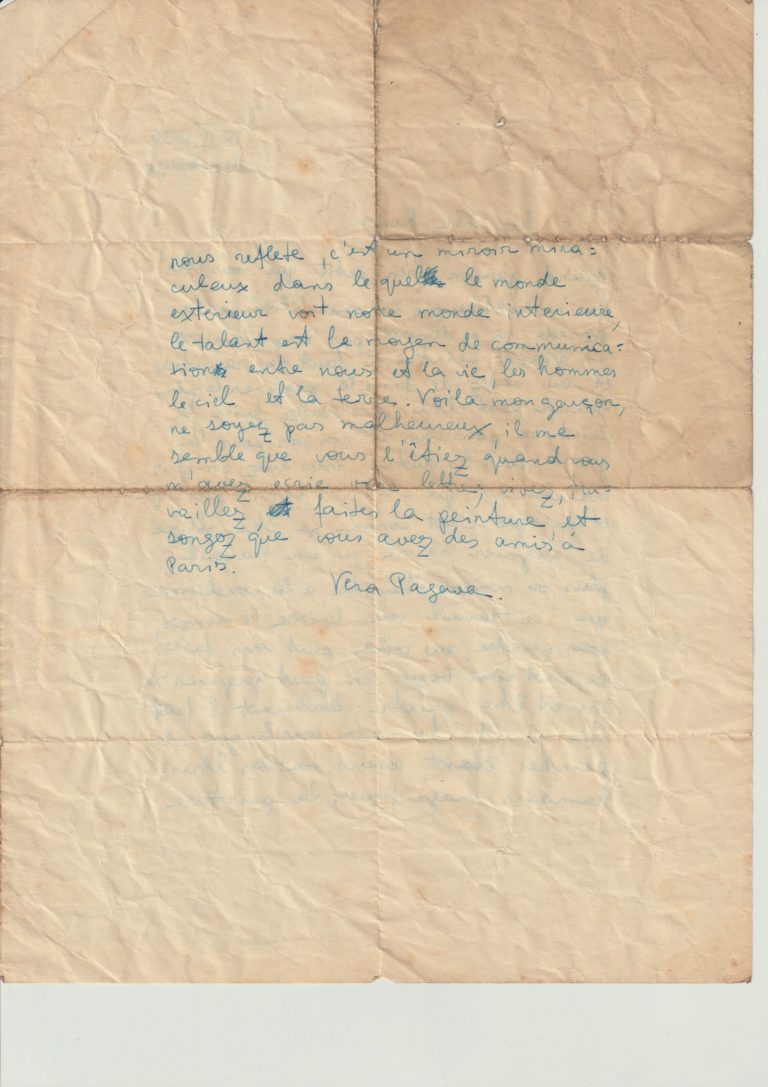

While Pagava took many steps in favor of abstraction, her formal decisions and color choices remained entwined with characteristics of her earlier works. Gradually, she completely abandoned figuration in favor of abstraction, settling upon the style she is most known for today. As if illuminated from within, her abstract forms suggest multiple planes on the surface of the canvas, which is devoid of corporeal and mundane qualities. Irregular shapes are fluid, morphing one into the other in harmonious compositions in which rectangular and triangular shapes have no sharp edges, but rather are soft and rounded. As her career progressed, Pagava sought to depict pure abstract forms in perfect equilibrium and harmony. Her later work can be described as spiritual, the product of her “inner world,” as she wrote in 1936 to British painter Roger Hilton (1911–1975),6Vera Pagava to Roger Hilton, April 15, 1936, Association Culturelle Vera Pagava—AC/VP. Translated from French to English by Olivia Baes. who was her close friend. On this rare occasion, an otherwise quiet and reserved person shared her ideas about art and the role of an artist: “It’s all right, Roger, you can earn a living and be a painter; you just have to be a human being, all the great painters were, above all, magnificent human beings. Painting reflects us, it is a miraculous mirror in which the outer world glimpses our inner world, talent is the means of communication between us and life, us and men, us and heaven and earth.”

While Pagava’s miraculous mirror reflects the modernist thinking characteristic of Paris in her time, it also reflects inward, into the deeply rooted Georgian influences she carried with her. Vera Pagava’s legacy is one of the rare artistic practices in which Georgian painting tradition is not only transformed into the language of modernism, but also stands as an intersection between the two. It is likewise yet another example of how the diaspora absorbs and profoundly shapes the art scenes of the artists’ new home countries.

- 1Georgia was a Democratic Republic between 1918 and 1921, when it was annexed by the Red Army.

- 2Vera Pagava, Peintures, Galerie Darial, Paris, May 3–June 17, 1972.

- 3Quelques peintures de Dora Maar et Vera Pagava, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, June 13–30, 1944.

- 4Ketevan Magalashvili was a famous portrait painter and among the pioneering Georgian women artists working in this genre. She studied painting in Tbilisi with acclaimed Georgian artist Mose Toidze (1871–1953) and then continued her studies in Moscow under painters Konstantin Korovin (1861–1939) and Nikolay Kasatkin (1859–1930). Between 1923 and 1926, she studied art at the Académie Colarossi in Paris. She worked at the Georgian National Gallery, which was newly established by her life partner, painter Dimitri Shevardnadze (1885–1937). Together, she and Shevardnadze were influential in Georgian cultural circles. Magalashvili is known for her portraits of the cultural workers and other cultural actants in Georgia at this time. Her legacy is also important in terms of its historical and documentary dimensions.

- 5Niko Pirosmanachvili, 1862–1918, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée des arts décoratifs, 1969).

- 6Vera Pagava to Roger Hilton, April 15, 1936, Association Culturelle Vera Pagava—AC/VP. Translated from French to English by Olivia Baes.