From August 2022 to June 2023, over numerous correspondences on Zoom, e-mail, and Google Docs, artists and friends Julie Tolentino and Kang Seung Lee reflected on their decades-long practices in kinship, politics, performance, and queer history.

Wong Binghao: Julie, Kang, how and when did you meet?

Kang Seung Lee: I was introduced to Julie by Young Chung, founder of Commonwealth and Council gallery in Los Angeles, sometime in 2016. I think it was right before my second show at the space, titled Absence without leave (2017). I had moved to Los Angeles from Mexico City in 2013 and was not too familiar with Julie’s recent work at that time, though I knew of their1Editor’s note: Julie uses she/they pronouns interchangeably. work with ACT UP NY; her early collaborations with Ron Athey and others; their involvement with New York’s queer womxn’s space, the Clit Club; and, of course, the famous 1989 “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do” campaign by Gran Fury. Julie is a legend in many ways.

Julie Tolentino: I remember Young Chung talking to me about Kang’s work; I can’t recall when exactly, but it was long before we actually met. I had lived and worked in New York for twenty-seven years and had just moved to the Mojave Desert. I took a chance to define a practice that had been moving through performance, conceptual, and visual art. My introduction to the gallery exposed me to many local artists. I was immediately caught by Kang’s commitment to re-orientations of representation, presence/absence.

KSL: I vividly remember that my first encounter with Julie’s work was Future Gold (2014), their collaborative exhibition with her partner Stosh Fila (aka Pigpen) at Commonwealth and Council. It consisted of remnants of their recent performance in Abu Dhabi, such as honey, gold thread, and saliva that were “smuggled” to Los Angeles and mixed with silicon and mortar in a glass box with a steel frame. The artwork was permanently installed inside a brick wall in the gallery space, visible from both inside and outside of the building, and it became part of the architecture of the gallery. It almost looked like a fish tank full of amber-colored water lit by sunlight. Through this artwork, I began to understand Julie’s artistic ethos, particularly their consideration of the body as an archive of embodied knowledge.

JT: My first performance-based interactive exhibition at Commonwealth and Council, RAISED BY WOLVES (2013), was actually the basis of Future Gold, the work that Kang mentioned. RAISED BY WOLVES was an outreach to a new creative community, in which I sought out physical and conceptual contributions from fifteen local visual and performing artists that I then transposed into drawings on laminated cards. The audience collectively pulled three to five cards from the deck that I, in turn, responded to through an improvised performance. Each artist’s work would “work on” the other, and thus influence me and the objects and people in the gallery space. The exhibition left behind a permanent wall work entitled Echo Valley, for which we had painted an excerpted text from Shame: A Collaboration by Birgit Kemper and Robert Kelly on a gallery wall. Over time, my partner, Stosh Fila and I would age (that is, darken and blur) the hand-painted text. As an additional transformation, and after we toured the durational performance installation Honey (2013) in Abu Dhabi, we repurposed empty oud perfume bottles and smuggled the performance’s excess honey to create an intervention. Removing a concrete block from the wall, we inserted a handmade thin glass container into the opening. The container was filled with the gold metallic thread, saliva, and honey from the performance. The work was renamed Future Gold.

The first work of Kang’s that I encountered was a wall mural that was part of a collaborative piece with Young Joon Kwak and Candice Lin. It emerged soon after RAISED BY WOLVES. I recall that the collection of work was situated on two walls, with a piece hanging from the ceiling, and a soundscore that accompanied it. It was near a door that is often left open and traversed—a social doorway. This work continues to hold significance for me as it embraces and holds my own wish for intergenerational, interdisciplinary, East-West art-activist-queer collisions, and transnational exchange. It was more “writing on the wall,” carrying collective love and many kindred conversations among us. It was a stunning way to meet Kang as I was already in love with Candice and Young Joon.

WBH: Kang, what do you remember about the collaborative work/exhibition that Julie mentioned?

KSL: The artwork is a collaborative installation in a hallway of Commonwealth and Council and was assembled by Young Chung. It consisted of my wallpaper installation Untitled (William Yang_The Morning After_1976) (2016) with Young Joon’s hanging mirror ball sculpture and Candice’s sound piece. I remember Candice’s work was played using a cassette player, and Young had to replace the battery almost every day.

WBH: In what ways have you collaborated since your first encounter? Are there any ideas or projects that you’d like to embark on together but haven’t gotten around to?

KSL: Julie’s engagement in queer activism, kinship, and care are especially pronounced in her work Archive in Dirt (2019–ongoing). The work, also known informally as “Harvey,” is a living cactus that Julie revived, that had been propagated from its “mother” plant that originally belonged to the activist/politician Harvey Milk. It came from their friend, an archivist in the special collections department at UCLA, who acquired cuttings from one of Milk’s ex-roommates in San Francisco. When I saw the work for the first time in the exhibition Altered After curated by Conrad Ventur at PARTICIPANT INC (July–August 2019), which both Julie and I were part of, the plant was quite fragile, with just one new, pale green leaf sprouting. The plant is a container of multigenerational memories of activism and connections in constant transformation as it grows and multiplies.

In 2020, Julie allowed me to include Archive in Dirt in Becoming Atmosphere, my collaborative exhibition with Beatriz Cortez at 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica. I thought of it as a gesture of transference of intergenerational responsibility and care to Beatriz, me, and the staff at the gallery. With the help of Julie and Young, I became a participant in the evolution of the work through making ceramic planters and repotting the plant, taking care of cuttings, and sharing them with other members of the community, documenting the growth of each plant, making drawings and mapping connections, etc. In 2021, I extended this gesture by including Archive in Dirt in Permanent Visitor at Commonwealth and Council, as well as in New York as part of my untitled installation for the 2021 Triennial at the New Museum.

JT: After submitting Archive in Dirt and my accompanying anxious, Siri-mediated catalogue text for Altered After, which was part of Conrad Ventur’s Visual AIDS project, I was pleased to learn that Kang and I were showing together, and that our works were in proximity to each other. I sensed a mutual responsiveness to the intricacy of Kang’s gold-threaded embroidery on the floor of the gallery and the liveness of “Harvey.” As Kang mentioned, Harvey was a cutting, gifted from friend, beloved, anarchist, educator, archivist Kelly Besser from the still-here garden of Harvey Milk in San Francisco. A gift from a friend of his, then a piece shared with me. My best guess after some research is that its genus may be derived from the Schlumbergera russelliana—a species pollinated by hummingbirds. It’s understood that the birds stab the seed with their beak, then rub it off onto the bark of a tree, which is an impetus for germination and, too, that this species often gives pink or reddish flowers. The particularly opaque seed interests me as it is known to not open easily, and thus needs intervention and movement for growth. I resonate with this personally and related this to the Archive in Dirt’s origin as a gift. Community and archival care are both a form of conjuring and a way to see oneself in others.

Harvey, the succulent, had endured plane trips, various re-pottings, and imperfect conditions in an effort to find its roots as an artwork. It was extremely fragile in the post-exhibition transition—a very key moment for its multi-future as it was sprouting and rooting in different locations, under extreme changes. It was shared with Conrad, Kang, Commonwealth and Council/Young, and was eventually returned home to Pigpen and my apartment in Northern California—just seven miles from its original home, the activist Harvey Milk’s rooftop garden. Everyone received these tender shoots—experiencing the responsibility of the split, transfer, transition, and reach. Kang posts how Harvey is doing and installed Harvey in a show at the New Museum. There is a rich three-way text thread running between Young, Kang, and myself. Conrad touches in from time to time, and we all gasp at the flowers and any tiny offshoots—signs of life.

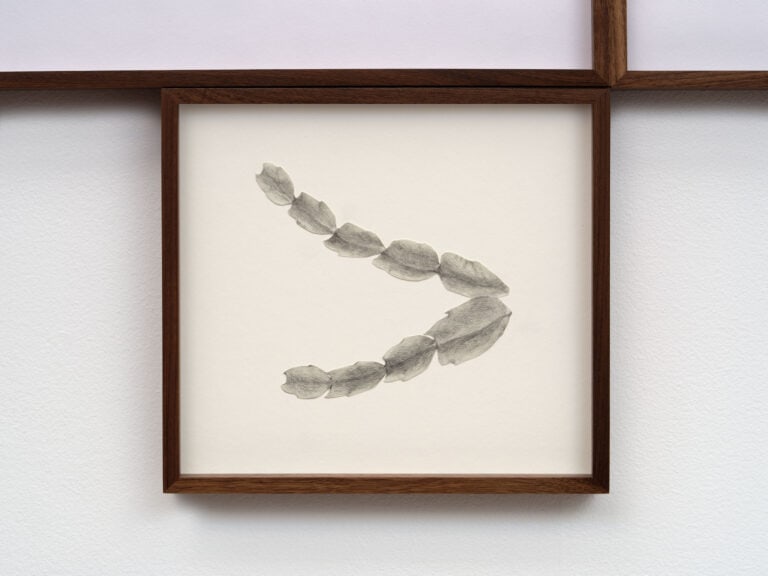

KSL: Skin (2021) and Untitled (Skin) (2021) are two other works in Permanent Visitor that came out of our conversations. Drawing from Julie’s consideration of the body, I was thinking about tattoos and scars as bearers of and witnesses to memories, pain, trauma—a mode of knowledge inscribed directly into the body. The two works are my attempts at capturing lifelong transformations through aging. I scanned the skin of Julie and three other friends: artists Jen Smith, Jennifer Moon, and Young Joon Kwak, who are all represented by Commonwealth and Council, trying to map a multigenerational fabric of our community’s embodied experiences. Skin is a video work in which the scanned images from the four artists are mixed together and move from one screen to another, resembling a flow of a river or human text as one collective body. In the floor installation Untitled (Skin), I embroidered these tattoos and scars on sambe cloth in antique 24-karat gold thread and juxtaposed them with fossilized leaves, seeds, and copper from the Pennsylvanian and Eocene eras. Sambe, a woven hemp textile, is traditionally used in Korea for funeral shrouds. Through the use of these materials, I was trying to honor our shared personal histories, address mourning and reverence, and reimagine collectivity through the flows of forces beyond one single life.

JT: Our bodies are laced together in Skin, tracing an opaque history that is built into the way we find ourselves drawn together—both with and onto each other. We are all UNEVEN in our togetherness—key to the way we use the archive. I lean toward the term “COUNTER ARCHIVE” to activate a liveness in oral recollections—that is, the liveness in the work shares the touch of Harvey, not a representation of Harvey Milk. This is not a critique so much as it is allowing terms around and between us that I experience as productive and queer.

I imagine that we take part in artworks and exhibitions as a kind of “forever practice.” Perhaps what I am saying, especially in the proposition in the tender-holding of Archive in Dirt as an archival expansion, is that we will always have opportunities to think with this kind of affiliation—as advocates for those among us and ourselves. This is always-in-process as our terms shift, as our surroundings and bodies change. I believe that Harvey and all the simpatico Harveys are part of a speculative forever-invitation offered to me—and thus, an Archive in Dirt translates as a verb: a care that is active, in action.

I hope that we can find ways to continue to talk at all the various stages of our encounters with Harvey. I feel like this interview across time, distance, space, caregiving, touring, artmaking, teaching, research, etc. is a form of continued public and privately negotiated dialogue, writing, and rewriting.

WBH: What first drew you to your engagement with queer histories (for example, genderqueer clubs, community organizing, HIV/AIDS activism) in and/or beyond art?

KSL: Growing up in Korea in the 1980s and ’90s, I was very frustrated with the lack of representation of queer people in the mainstream media. My mining of queer archives definitely started from the desire to be connected and to be part of a lineage. It also meant negotiating with Western-oriented hierarchies that shaped the narratives and histories of the queer community, a complex position for queer Asians, who face oppression and homophobia within their own culture while being on the margins of the White Euro/US–centric queer culture.

As I go back and forth between Los Angeles and Seoul, I try to find ways to contribute to the queer communities in both countries from my privileged transnational position. For example, for the past four years, I have worked with QueerArch, also known as Korea Queer Archive, a personal archive of activist Chae-yoon Hahn that was established in 2002 but became public soon after.

I make use of resources and funding opportunities from the contemporary art world to exhibit collections of books, magazines, newsletters, etc., and items such as ephemera from Pride parades from the archive, collaborate with younger generations of queer artists based in Korea creating new works influenced by our research at the archive, and also include items from their publication collection within my participation in the biennial in Gwangju, among other venues.

My projects are rooted in archival research. I try to reposition queer archives and collections, to connect distinct geographies and experiences to forge new sites of knowledge. For example, in my 2018 exhibition Garden, I juxtaposed the artworks and lives of two activist-artists, Oh Joon-soo and Derek Jarman, who were from two different continents but both died of AIDS in the 1990s. In a series of drawings on paper called Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi) (2018–20), part of which was exhibited in a recent solo exhibition Permanent Visitor, I appropriated and attempted to create a critical context and history for the Hong Kong–born artist Tseng Kwong Chi’s works. I want to keep the legacies of these artists and HIV/AIDS activism alive to challenge dominant whitewashed narratives.

JT: I grew up deeply impacted by early LGBT and race riots in San Francisco, raised by teen parents and first-generation Filipino and El Salvadoran immigrant grandparents. Language and access bore down on how we navigated progress narratives, access, the reality of living with and among HIV and AIDS, the various forms of belongings and the righteous making of lives through clubs, affinities, drugs, difficulty, disabilities, art forms. . . . In retrospect, I learned to take in isolation as something to address, support, and surround, yet also allow myself to identify and work with. I look at how archives can be challenged to examine and champion other kinds of marks and signs of life—to see into the shape of (im)possibilities. Our experiences are uneven and this is important to remain open to. Legibility can also be elusive, exclusive. Relationships are dreams that need care. Art-making helps us reimagine ways towards another—and along queer lines, past and future.

WBH: How does dance figure (or not) in your artistic practice?

KSL: I am currently working on a new project The Heart of A Hand, which pays tribute to Goh Choo San (1948–1987), an internationally renowned Singaporean-born choreographer who died of an AIDS-related illness at thirty-nine years old. During his lifetime, he performed and choreographed for prominent ballet companies throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States. His legacy remains largely absent from dance history in the United States, most likely due to his diasporic identity. His accomplishments have been slightly more recognized in Singapore, perhaps fueled by nationalism, but his place in global queer cultural contexts is still vague.

The research process for this project has been quite challenging as I had to follow traces of Goh’s inherently ephemeral work and life between worlds. Last summer, I took a very rewarding trip to Singapore, where I met with a group of queer artists and cultural workers who helped me move through the huddles: Ming Wong, Jimmy Ong and, of course, Bing, who made all the connections. It felt like we were on a mission to learn about this queer predecessor and his last years, and I had a realization that the invisible memories of queer lives can only be sustained by this kind of cross-generational curiosity.

Through Janek Schergen, Goh’s friend and ballet master, and his sister Goh Shoo Kim, I learned much about Goh’s last years in New York City; his partner Robert Magee, who died of AIDS-related complications a few months before Goh; and how they were looked after by a group of friends for the last year as they became weak. I am trying to find ways to address these untold memories and to convey the ongoing grief and their bodily experiences of caregiving and resistance. The centerpiece will be my collaboration with Joshua Serafin, a performance artist born in the Philippines and based in Brussels. We are in the process of creating a video inspired by Goh Choo San’s Configurations (1982), a queerer, nonconforming, and clubby version, of course.

JT: Dance—ah, so much to say here. I left capital D dance long ago, having trained via a queer, brown, not-designed-for-dance, classed, and racialized body. Coming up, out, and through formal training in the ’80s highlighted how my formation was imbued with mixed racialization—a kind of triple-dosed consciousness and its special brand of impacting encounters with classism, racism, and homophobia. Though it lingers, forty years ago, being an “imperfect and unrecognizable” body in the dance room, in its skinny mirror and stage that prizes the spectacle, there was always something to work through (resist) and break with (refuse). Movement (and movements) create choreographies of being with and listening for other bodies, speculatively echoing back and forth across time.

I worked professionally in David Roussève’s REALITY, originally a predominantly Black experimental dance company for twelve years. With many other artists, I contributed as performer/mover in more theatrical settings and this propelled my own practice into movement-based durational performance installation in the mid ’90s, when I experimented with folks like Grisha Coleman and Patty Chang. Years later, for my own work The Sky Remains the Same (2006–present), I archived works of other body-centered artists such as Lovett/Codagnone, Athey, and Franko B, as well as choreographers David Roussève and the late Stanley Love into/onto my body as a form of advocacy and community recognition expressed as curation<!>—while fully acknowledging the inadequacy of such a claim due to my own (disintegrating) body. This leans heavily on the necessity of movement—its weight, space, time, gathering.

Movement always leads, as in the 108-hour durational performance and visual art exhibition entitled REPEATER (2019) or the invitation to float and submerge, one-on-one, with audience members underwater in a gold-lined tent and cedar pool in Slipping into Darkness (2019). In recent collaborative and durational performances ECHO POSITION (with Ivy Kwan Arce, 2022), HOLD TIGHT GENTLY (with Stosh Fila, 2022), and LET’S TALK (with Jih-Fei Cheng and other artist/activist/writers, 2022), I consider the potency of collective movement embedded in light, reflection, and glass to call upon the voices of past and future to help us express stealth learning and the intricacies of public and private mourning, kink, care practices that are moving, and complex forms of love. There is so much more to say about the role of dancing and its material contagion—alone, on stage, slow drags, stuck in things, or just being the last messy one still swaying at the bar. Perhaps it’s the feeling of a kind of melancholic punk lingering, an in-person pulsing that remains. All that submerged melancholy drenched in fierce dancer epaulement. A nod to improvisation, ball culture, and the blues. All that swish. . . There is a kind of loosening I aim to engage in as a form of touch. A rigorous shaking (it up).

- 1Editor’s note: Julie uses she/they pronouns interchangeably.