On the evening of October 12, 2022, post presents hosted presentations and conversations with artists, scholars, and curators about the artistic responses to the war in Ukraine, looking at the period between the Maidan Revolution, which was followed by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of Donbas in 2014, and the full-scale Russian invasion launched on February 24, 2022.

During the event, art historian Svitlana Biedarieva talked about the development and transformation of documentary practices in Ukrainian wartime art, analyzing works by Dana Kavelina, Vlada Ralko, Alevtina Kakhidze, and Yevgenia Belorusets. Researcher Ewa Sułek expanded on her proposal that what happened in the visual arts after 2014 can be named a “postcolonial turn”—a phenomenon based on healing and the acceptance of history and of the past in its hybrid form, without the imposition of imperial or national patterns. Artist Lesia Khomenko discussed her own practice, which is currently focused on ways of looking at the war and the relationship between the digital archives and the materiality of painting. And Nikita Kadan spoke about his own practice, which references the Ukrainian avant-garde and modernism.

This conversation is a continuation of the presentations and conversations commenced that evening.

Inga Lāce: The full-scale war has been going on for more than a year. Could you say where you’re at now, and share a few words about how your surroundings and the cultural landscape have changed.

Ewa Sułek: I am currently in Warsaw, and the city has changed tremendously—Ukrainians have become part of the urban fabric. Works by Ukrainian artists are widely exhibited, and Polish art institutions are making an effort to enable refugee artists to live and work here. When the war started, I was at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, very far from Ukraine and from my own country. While all of my Polish friends were engaged in a massive, beautiful effort to help the millions of Ukrainian refugees arriving in Poland, I felt useless. But my perspective changed once I realized that one of the reasons this war is mainly understood as colonial is that all imperial and colonial powers aim at denying subjectivity to their subjects. This reality has been influencing Ukrainian history and culture for centuries but, once revealed, can become a powerful tool of subversion. So now is exactly the time when art and academic work in Ukrainian studies as separate from Russian ones is important. I have recently completed my PhD on contemporary art centers in Kyiv from the postcolonial and neocolonial perspectives, and I am planning to publish it as a book.

Svitlana Biedarieva: In January 2022, I talked with Ukrainian artists Alevtina Kakhidze, Maria Kulikovska, Piotr Armianovski, and Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dostliev for October about the wartime experiences of displacement and loss reflected in their art, and we also discussed the then-hypothetical threat of Russia’s attack.1Svitlana Biedarieva, “Art Communities at Risk: On Ukraine,” October, no.179 (Winter 2022): 137–49, https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00452. Based on their responses, it was apparent that, at that time, such a rapid and violent turn of events seemed completely unlikely. But then the reality proved to be worse than the most pessimistic predictions.

The war-related displacement from 2014 that had affected the cultural landscape of eastern Ukraine and Crimea became the new reality for the rest of the country in February 2022. Violence and destruction in the suburbs of Kyiv reinforced the vulnerability of human life. Many artists and researchers have been forced to continue their work outside Ukraine, but rather paradoxically, this movement provided a new opportunity to globally showcase Ukrainian culture, which until recently, was largely overlooked.

We saw much more radical forms of antiwar and anti-colonial expression. Artists and curators became more decisive and direct in their discourse, tracing the causes and consequences of the aggression through personal lenses—as direct witnesses to or victims of violence—and they set an important precedent for antiwar resistance through art in Eastern Europe, catalyzing the final dismantling of post-Soviet space together with its postcolonial agenda.

Lesia Khomenko: Immediately following the full-scale invasion, I evacuated my family from Kyiv while my husband joined the Territory Defense Forces. I moved to the United States with my daughter, and we are now based in Miami at an artist residency. Since 2014, a lot of artists from eastern Ukraine and Crimea have moved to Kyiv. There was a very interesting, dynamic exchange in the art community there between those who worked with the issue of war, observing it from outside, and those who had been forced to leave their homes, to run from the war. Now, as of February 24, 2022, there is no such difference.

Before fleeing to the US, I had been deeply involved in developing alternative art education in Ukraine beyond just Kyiv. The institutional landscape was fragile but developing fast. A lot of artists were investing their energy in expanding the context of their practices by curating, teaching, establishing residencies, or opening artist-run spaces. Since February 24, most of these new institutions have been in survival mode or functioning as volunteer hubs.

IL: Svitlana, you have been researching artists’ documentary practices since the beginning of the war in 2014. Could you elaborate on how narratives created by Ukrainian artists have shifted since the full-scale invasion in February 2022?

SB: I wrote in detail about the turn to documentary art in 2014 in the book I recently edited called Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art: Political and Social Perspectives, 1991–2021.2Svitlana Biedarieva, ed., Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art: Political and Social Perspectives, 1991–2021, Ukrainian Voices, vol. 14 (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2021). Directly following the Maidan Revolution and Russia’s occupation of eastern Ukraine and Crimea, artists such as Yevgenia Belorusets, Piotr Armianovski, Alevtina Kakhidze, Mykola Ridnyi, Andrii Dostliev and Lia Dostlieva, and Dana Kavelina—among many others—engaged with the effects of war by undertaking documentary practices incorporating photography, text, video, and existing archives and creating new accounts focused on notions of displacement, violence, and trauma.

Researchers Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg point out that this “documentary turn” has emerged globally in response to the postcolonial transformation, when artists turned their gaze away from the centrally produced body of ideas to take up diverse local perspectives, especially through direct, often raw visual language—as has been true in Ukraine.3Erika Balsom and Hila Pelef, “Introduction: The Documentary Attitude,” in Documentary across Disciplines, ed. Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, with Martin Hager (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 15.

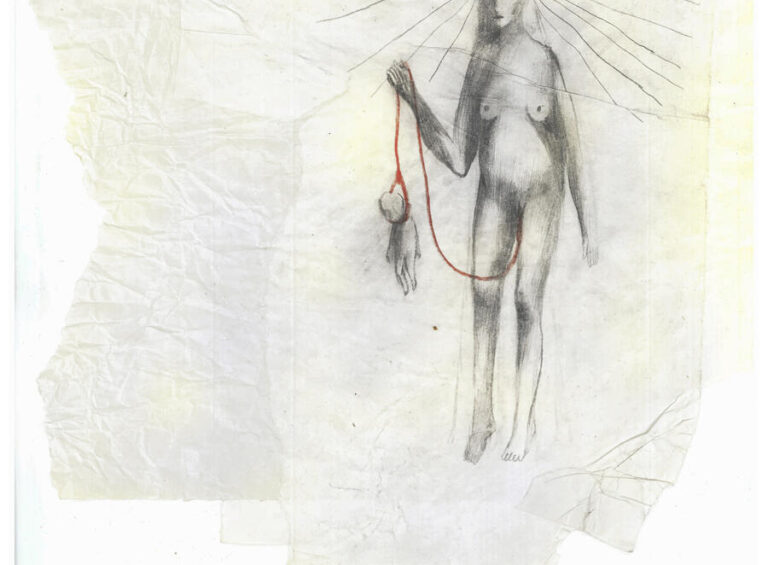

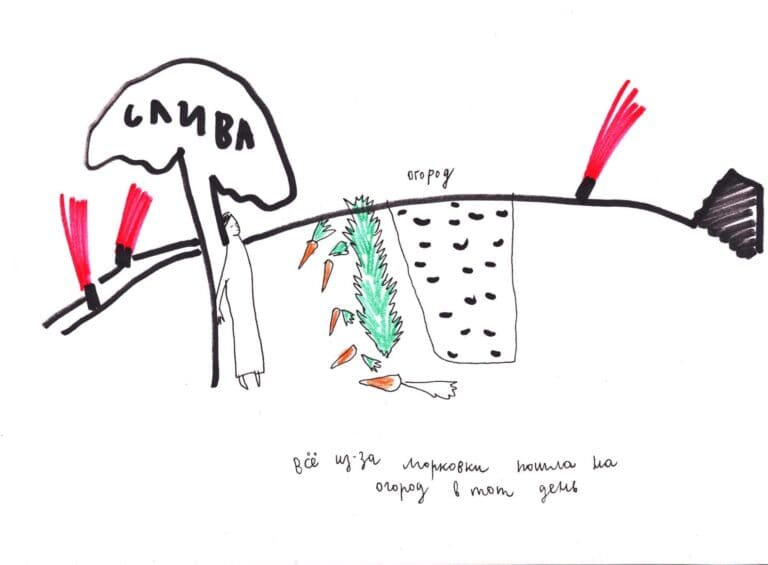

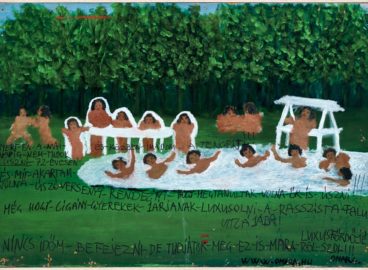

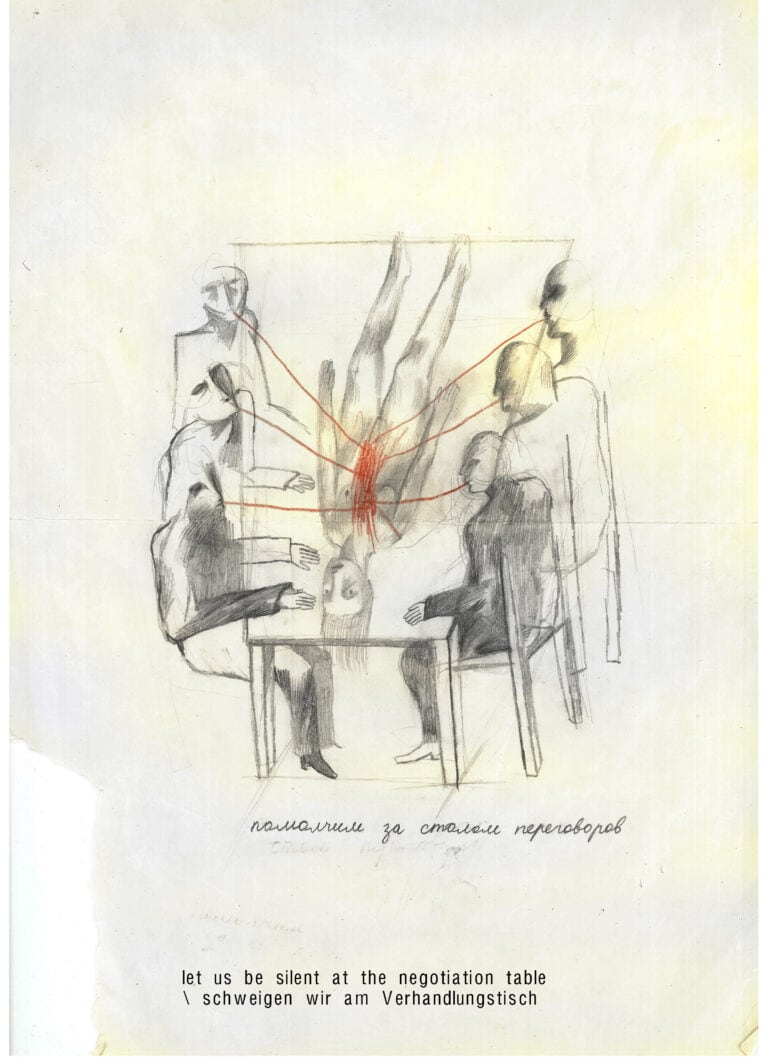

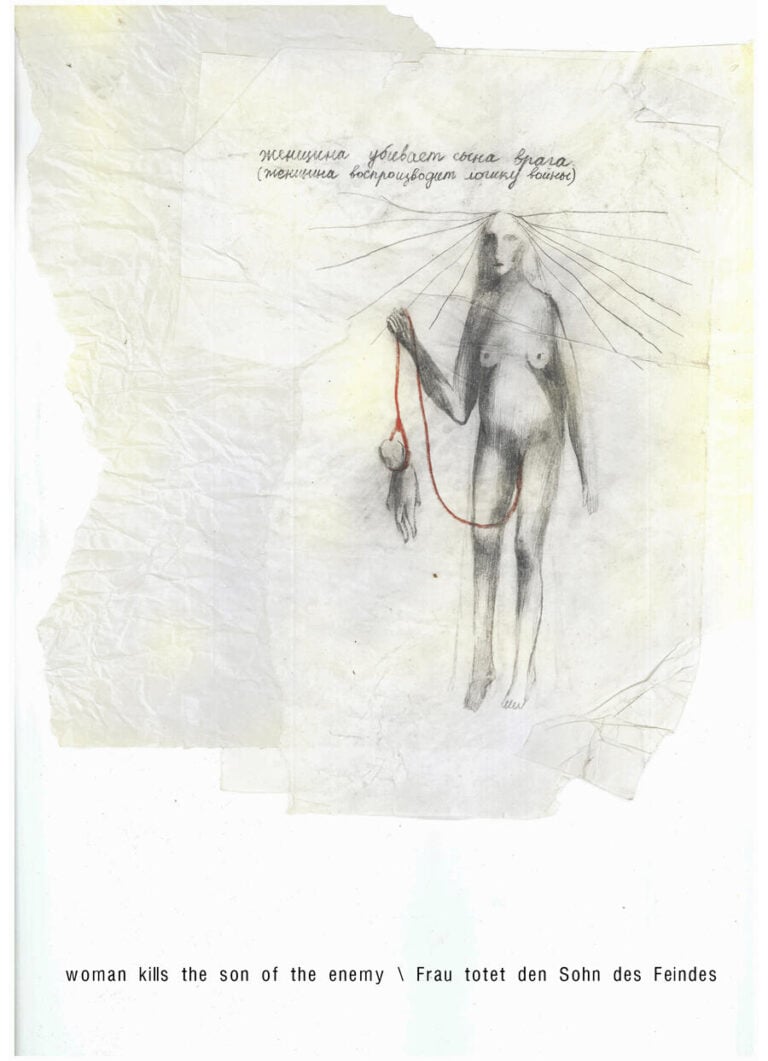

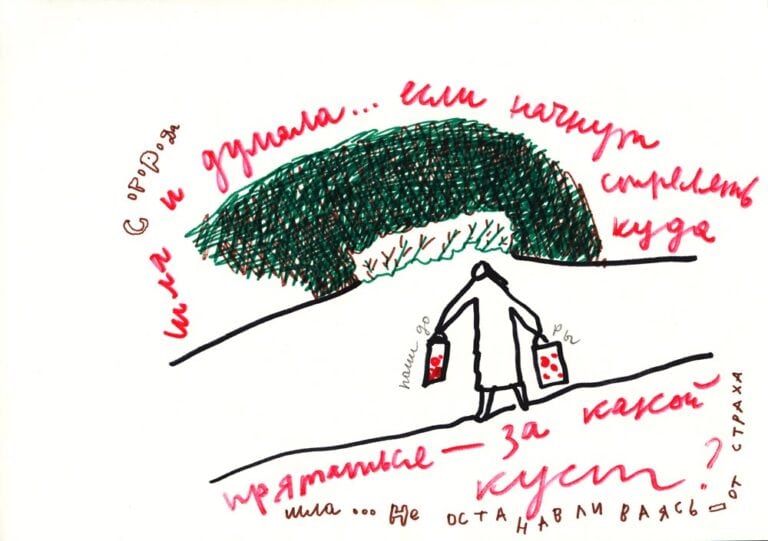

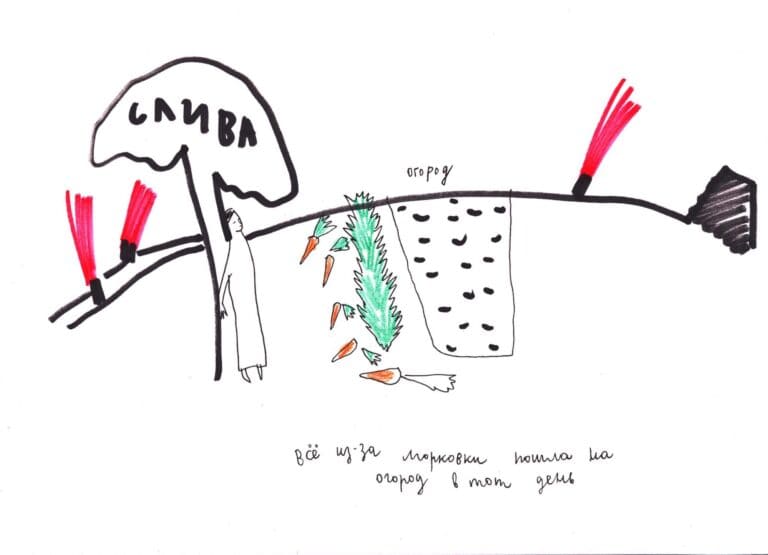

Post 2022, there has been another turn in the ways that mediation has moved from social documentation and archival investigation to personal chronicle, in which the different visions of the artist’s diary—in the work of Kakhidze, Vlada Ralko, and Yevgenia Belorusets, for example—have become an emblematic form focused on trauma, the body, identity, and decolonization.

The task of documentary practices now is also to emphatically reflect on the audience’s own traumatic life experiences of destruction and human losses. The question of historical memory has become secondary.

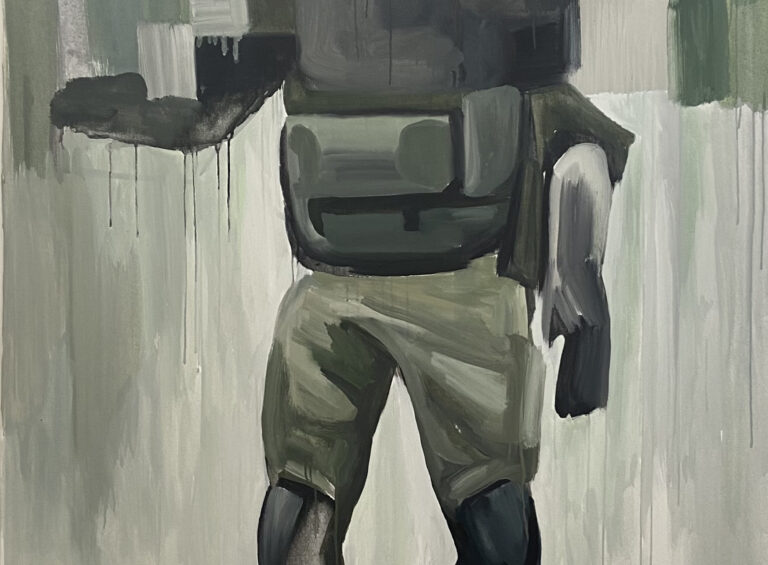

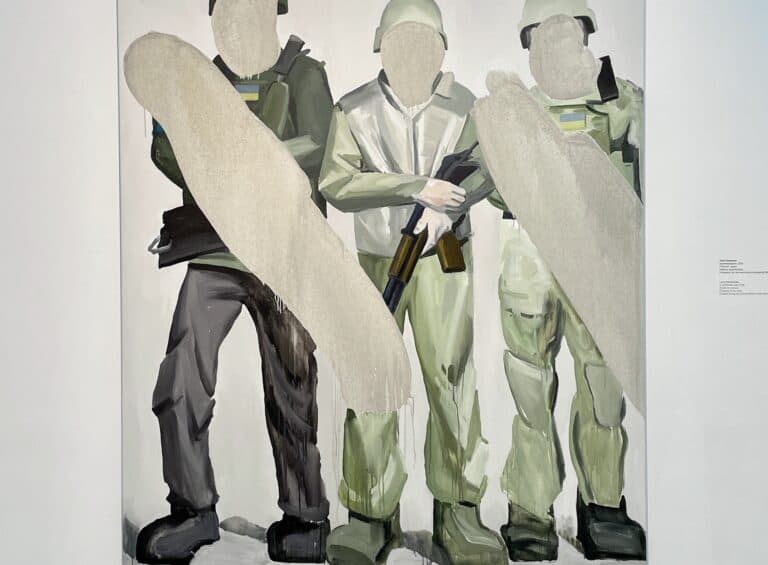

IL: Lesia, you talked about the development of your practice, ending with your recent series Max in the Army (2022). So, I’ll start with that. What was the impulse for making this series, and what does the work open up in relation to digital technologies and images of war?

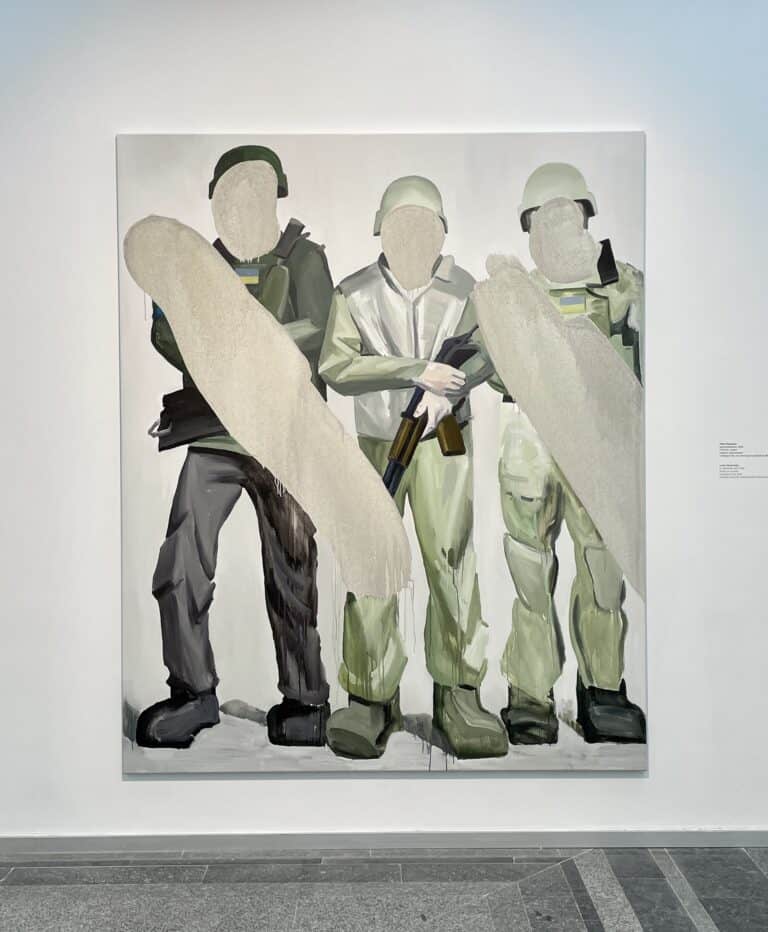

LK: It’s my first work after the full invasion and my escape from Kyiv. I depict my husband Max Robotov, who is an artist and musician, in the first weeks after he joined the army. I was curious how being a lieutenant had changed him. Early on, he sent me a photo of himself saluting in front of a dark and unclear background. He was in civilian clothes—as were most of the soldiers at the beginning of the war. This image epitomizes my personal experience of the war. The idea of the series is to reflect the merging of civil society and the army.

Since the full invasion, people are no longer allowed to take photos or videos of soldiers or military objects, because sharing them might give the enemy intelligence for an attack. Working on this series of paintings, I have been reflecting on the role and status of the image, which in the context of war has become a potentially lethal weapon. I’m using the photos that I have received from my husband—taken from outside his army unit—as well as footage circulating in the public sphere.

I’m referencing the history of battle painting and, at the same time, thinking about the role of the image and of representation in the context of the cyber war.

IL: Lesia, you and many of your peers got their education in post-Soviet Ukraine. How do you think the local education and museum system has affected your work and imagery and attitude toward painting?

LK: At my alma mater, painting is deeply rooted in the post-Soviet visual tradition, which, for me, is both problematic and productive. The programs in the state art academies in Ukraine are still based in the traditional school of the nineteenth century—corrected just a little during the Soviet period but almost unchanged in the post-Soviet period. By deconstructing the visual language of Soviet figurative painting, I’m rethinking the tools of Soviet propaganda and mythologization by comparing them to recent phenomena in the cyber war. I’m working not only with the idea of narrative but also rethinking the academic approach to producing images and to “realism” by using the method of copying or referencing traditional genres such as landscape, historical painting, or portraiture.

IL: Ewa, you talked about the curatorial strategies employed in Kyiv museums, which are rethinking their own art history, for example, bringing attention to self-taught artist Maria Prymachenko, who was falsely provincialized as the “happy peasant” by Soviet authorities. Can you delve a bit deeper into these curatorial projects and explain the context and intention behind them?

ES: I mentioned three projects in Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv: Kateryna Bilokur. I want to be an artist! (2015) and Mariya Prymachenko. Boundless (2016), both of which were curated by Alisa Lozhkina, and Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit. Overcoming Gravity (2019), which was curated by Kateryna Radchenko. These exhibitions aimed to re-narrate the work and lives of the self-taught Ukrainian women artists who were practicing in Ukrainian provinces during World War II and throughout the Soviet period. Bilokur’s and Prymachenko’s work, although widely recognized, was celebrated mostly for its floral or animal motifs or decorative patterns and thus fell into the category of folk art. In Soviet times, the myth of the Ukrainian village as the source and essence of Ukrainian culture was a state-supported construct that helped in colonizing the country, and so the artists were well supported by the regime.

Bilokur’s and Prymachenko’s work was seen back then as cheerful and optimistic, features that were desired in that they conformed to Stalin’s cultural policy that art should express the joy of the communist system. In fact, the policy of folklorization of Ukraine dates back to the Russian Empire. A similar policy was executed toward the Ukrainian language, which was perceived as a dialect of the main language—that is, of Russian.

Overcoming Gravity was devoted to a reinterpretation of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit’s work. A painter, folklorist, ethnographer, philosopher, and photographer, Plytka-Horytsvit lived and worked in the small village of Kryvorivnia, and she led a solitary life devoted to artistic and ethnographic practices. Her life was also marked by tragedies universal to many at the time—she joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and in the 1940s and ’50s, and spent almost a decade in labor camps and prisons in Germany and Siberia.

IL: Nikita, your projects are dealing with the historical references of avant-garde art and Soviet modernism. Could you elaborate on your strategy for dealing with the past, for unearthing these stories? Why is it important and what is your position with regard to it?

Nikita Kadan: I deal mostly with the ruins of the avant-garde. These ruins are covered with nationalist and neoliberal decorations, which aim to hide too radical universalist and internationalist intentions. I see my task as uncovering or unmasking these avant-garde intentions. “Back to avant-garde” means “back to universalism,” and the latter is no less paradoxical than the former. We have to go back to be able to restart the way to the future.

But local creators of universalist avant-garde work were often imprisoned and executed by the state for being “too Ukrainian.” The state publicly declared internationalist values but, in fact, reestablished a Russia-centric imperial structure for the Soviet republics and their cultural life. “Unearth” is a good word here—really. The remains of Ukrainian avant-garde creators are literally found in death pits in places of mass executions, like Sandarmokh.

The future is to be found in an execution pit—this is the horizon of the new utopia.

IL: There have been attempts across the Central Eastern Europe and Central Asia, especially the former Soviet Union countries to place their histories within the postcolonial debate and decolonial discourse. The recent full-scale invasion of Ukraine has amplified this approach among others with calls for decolonizing Russia. However, even though they share imperial domination with the postcolonial countries, their histories are very different. How, in your opinion, can we use the framework of postcolonialism and decolonization to speak about art in Ukraine?

ES: The story of Russian imperialism in Ukraine goes back much further than the Soviet Union, and a postcolonial perspective can be useful where there are relationships of domination and power that are imposed by imperial structures, like the relationship between Russian and Ukrainian cultures. I also find the concept of “coloniality” proposed by Aníbal Quijano and developed by Walter Mignolo and others helpful. While “colonialism” is a specific historical condition, “coloniality” emerged at the same time (in around 1500), and includes both imperialism and capitalism. It is not as much connected to the prevailing concept of the colony overseas based on geographical distance and racial distinctiveness, but rather to other factors stemming from the rhetoric of modernity, progress, and development. In that sense, the continuous narrative of Ukrainians as “little Russians”—meaning underdeveloped—also finds its place within this discourse. Furthermore, colonization is not only about territory, culture, or economics. There is also the colonization of minds, which likewise stems from the modern “civilizing mission,” and it includes communism.4Madina Tlostanova,“Postsocialist ≠ Postcolonial? On Post-Soviet Imaginary and Global Coloniality,” in “On Colonialism, Communism and East-Central Europe—some reflections,” special issue, Journal of Postcolonial Writing 48, no. 2 (2012): 132.

SB: My most recent research is dedicated to the dichotomy of postcoloniality/decoloniality in contemporary Ukrainian art and culture. I also employ a typology formed by [Madina] Tlostanova, who distinguishes between postcoloniality and decoloniality not only from a paradigmatic point of view, such as the postcolonial theory that was developed by such theorists as Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak and the decolonial theory by Latin American scholars Walter Mignolo and Aníbal Quijano, but also from a chronological perspective. The postcolonial development in Tlostanova’s model immediately follows the anti-colonial resistance and resulting downfall of an empire when a society of a now-independent country reworks its recent colonial experience.5See Madina Tlostanova, “The Postcolonial Condition, the Decolonial Option, and the Postsocialist Intervention,” in Postcolonialism Cross-Examined: Multidirectional Perspectives on Imperial and Colonial Pasts and the New Colonial Present, ed. Monika Albrecht (London and New York: Routledge, 2019), 165; Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994); Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,1999); Aníbal Quijano, Modernidad, identidad y utopía en América Latina (Lima: Sociedad y Política Ediciones, 1988); and Walter D. Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). The decolonial process, however, goes one step further in its liberation from any colonialism-related elements, which is exactly what we are witnessing today in wartime Ukraine. I believe, however, that a new theory is needed to describe Ukraine’s complex situation in the post-Soviet space. In my research and the book that is currently under contract with Palgrave Macmillan, I use this theory as a cornerstone for developing a model that would be suitable for the Ukrainian/Russian case.

My position is that art in Ukraine has recorded how Ukrainian society went through a postcolonial stage after 1991 and entered a decolonial stage in February 2022. First, artists are dismantling postcolonial narratives and substituting them with decolonial ones, and second, they are creating new content that conceptually breaks with the imperial legacy of Russia. The current traumatic experience of war serves as the impulse for decolonial transformations—from the anti-colonial calls to cancel Russian culture to the civilized decolonization of institutions of power.

LK: I consider decolonial discourse in Ukraine extremely important. Articulated since 2014, it is in its hottest phase ever. But there is a contradiction among Ukrainian intellectuals: some insist on complete decommunization and on the de-Russification of public space and culture, while others propose rethinking and the reappropriation of certain names and phenomena. I think that the role of artists in this process is very important, because artists build nonlinear narratives and are able to operate within a complex system of paradoxes.

IL: Nikita, in your prompt, you mentioned the changes in the perception of the notion of the avant-garde in post-1991 and post-2014 Ukraine, as well as the (im)possibility of a “national avant-garde.” Could you elaborate on this position?

NK: Early post-Soviet perception was part of Ukraine’s “multi-vector” position in the 1990s and early 2000s, when lots of imperial patterns in culture remained untouched. But the return of the Ukrainian avant-garde to the narrated history was often initiated by people whose position was rather conservative. [Mikhail] Semenko or [Valerian] Polischuk, [Maria] Siniakova or [Anatoly] Petritsky, [Boris] Kosarev or [Vasyl] Yermylov were observed through optics, in which “national” elements in their practices were seen as much better than “cosmopolitan” ones. And this very much differs from the original intentions of most Ukrainian avant-garde and modernist figures. On the other hand, the imperial phenomenon of the “Russian avant-garde” was not really questioned by decolonial thought and was not so problematic for many art professionals and audiences in Ukraine. So narrating avant-garde figures as conjointly Ukrainian, cosmopolitan, and non-Russian was like being between Scylla and Charybdis. 2014 made the “nation-centric” views more popular. At the same time, the field of discussion became broader, and the positions opposing both narrow national-conservative thinking and cultural neocolonialism became more visible.

IL: Could you talk about how your practices as researchers and artists have changed since the full-scale invasion in relation to representing a certain nation state and its art scene. I am thinking of many of our previous conversations, which have been full of ideas of cosmopolitanism, transnational research, and the fact that you are fundamentally international artists and scholars. However, with the war, the pressure to serve national representation seems to be very high. How does it resonate in your art and other activities? How do you negotiate this pressure?

ES: As a non-Ukrainian, I initially found myself doubting my right to comment on art practices in Ukraine now, since it is not possible to fully understand what it means to live and work in a country at war unless one personally experiences it. I have been working with Ukrainian art since 2014, and as a Polish scholar exploring Ukrainian topics, my postcolonial perspective has, at least a couple times, been criticized as a form of Orientalization. An interesting article titled “Explaining the ‘Westsplainers’: Can a Western Scholar Be an Authority on Central and Eastern Europe” was published by Aliaksei Kazharski in July 2022.6Aliaksei Kazharski, “‘Westsplainers’: Can a Western Scholar Be an Authority on Central and Eastern Europe,” Forum for Ukrainian Studies, July 19, 2022, https://ukrainian-studies.ca/2022/07/19/explaining-the-westsplainers-can-a-western-scholar-be-an-authority-on-central-and-eastern-europe/. It shows that we are maybe even more cautious now about who speaks about what and who is given a voice.

SB: I don’t see speaking about Ukraine or the war as the pressure to serve national representation, but rather as the only means of active protest against the war. Even though, currently, it’s very difficult to make any parallels or comparisons, in 2019, I spoke of the war in Ukraine to Latin American and Canadian audiences as part of the interdisciplinary project At the Front Line. Ukrainian Art, 2013–2019, which took place in Mexico City and Winnipeg. This was the first large-scale research-led project in Latin America focused on the war in Ukraine that addressed the common experiences of conflict, violence, and displacement. When speaking about Euromaidan, for example, we encountered a vivid response from Mexican audiences who remembered or even witnessed the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968; similarly, stories of Russian military violence in eastern Ukraine prompted comparison with the drug cartels’ violent actions in the north of Mexico.

LK: The current attention being given to Ukrainian artists is helping us to better articulate a lot of messages. At the same time, there is very high turbulence in Ukrainian society itself, and a lot of artists are balancing between pure propaganda and critical artistic gestures, between personal stories and general conclusions. These debates, as well as the visibility of artists is very important for postwar Ukraine.

IL: Even though there is this visibility, in the context of the current war, there is a danger that Ukrainian art and artists are reduced to speaking only about the war. How do you deal with that?

LK: I’ve been working with the issue of war for more than ten years. I had been researching World War II and working with the story of my grandfather and Soviet postwar paintings. Now I’m looking at the current war through the perspective of the role of the image and representation—and, of course, I’m thinking about commemoration and the creation of historical narratives. Footage of this war has made me think about how war affects the global civilization in general and what it means to be visible—how security issues and technology are changing our optics. Personally it’s difficult to think about anything else but the war. And, on the other hand, to convey knowledge of the war with nuance is extremely important to resisting the propaganda machine.

NK: Ukrainian artists speak about reality. And reality is impregnated by war. Landscape is a war landscape. Bodies are war bodies. It is a big shift in our sensitivity. Now you even don’t have to show war literally, directly—it is in your work anyhow. I still make work about forgotten and interrupted stories of Ukrainian modernism. About stories of local twentieth-century art history. But these stories are read through the lens of war. There is no other way.

IL: Our discussion takes place in the context of The Museum of Modern Art, thus an important issue for us is to understand how your research and artistic practices impact the art historical narratives and museum practices in relation to art from Ukraine. What is your take on that?

ES: It is important not to engage the norms imposed by the Western point of view, which tends to see Ukraine as “Other” and to exoticize the vaguely defined “East” as a continued form of silencing and trivialization by the dominant discourses. Eastern Europe has been an object of the colonial gaze from both the West and Russia, and a certain image of this place has been imposed. Less interest has been given to art from Ukraine or Poland than to work coming from Russia. Such an attitude strengthens the imperial status quo. Artists and researchers decolonize Ukraine by rewriting the story of the land and region from a Ukrainian as opposed to Russian perspective—discerning its uniqueness, and creating narrations distinct from those imposed in Soviet times and earlier, in the times of the Russian Empire—and, at the same time, recognizing the hybridity that emerged due to decades of existence in the frames of both systems.

SB: I agree with Ewa. For example, many artists, particularly those working in the 1920s–30s avant-garde, who were born or worked in Ukraine, are still labeled “Russian,” which of course is being corrected now with urgency but is still a process often flawed or lacking research. So involving Ukrainian art historians and curators can help a lot.

IL: Is there anything that you feel is missing in the discussion about art in and from Ukraine that you would like to raise here?

SB: Everyone’s talked a lot about the war. I believe that what is missing currently in the international discussion on Ukrainian art is taking into account its heterogeneity, development of the classification of its chronological stages, and critical currents linked to the personal position and style of each artist. Otherwise, in trying to develop a Ukrainian “trademark” in terms of art, we risk overgeneralization. But this art historical systematization needs to be undertaken with a certain historical distance, as it is often impossible to grasp the entire panorama while in the epicenter of war.

post presents: Art, Resistance, and New Narratives in Response to the War in Ukraine was co-organized with the Polish Cultural Institute New York and co-sponsored by the James Gallery at CUNY. Promotional support was provided by the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University.

post presents is a series of talks devoted to the cross-geographical consideration of modern and contemporary art. The sessions are an extension of post, MoMA’s online platform devoted to art from a global perspective.

- 1Svitlana Biedarieva, “Art Communities at Risk: On Ukraine,” October, no.179 (Winter 2022): 137–49, https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00452.

- 2Svitlana Biedarieva, ed., Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art: Political and Social Perspectives, 1991–2021, Ukrainian Voices, vol. 14 (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2021).

- 3Erika Balsom and Hila Pelef, “Introduction: The Documentary Attitude,” in Documentary across Disciplines, ed. Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, with Martin Hager (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 15.

- 4Madina Tlostanova,“Postsocialist ≠ Postcolonial? On Post-Soviet Imaginary and Global Coloniality,” in “On Colonialism, Communism and East-Central Europe—some reflections,” special issue, Journal of Postcolonial Writing 48, no. 2 (2012): 132.

- 5See Madina Tlostanova, “The Postcolonial Condition, the Decolonial Option, and the Postsocialist Intervention,” in Postcolonialism Cross-Examined: Multidirectional Perspectives on Imperial and Colonial Pasts and the New Colonial Present, ed. Monika Albrecht (London and New York: Routledge, 2019), 165; Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994); Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,1999); Aníbal Quijano, Modernidad, identidad y utopía en América Latina (Lima: Sociedad y Política Ediciones, 1988); and Walter D. Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

- 6Aliaksei Kazharski, “‘Westsplainers’: Can a Western Scholar Be an Authority on Central and Eastern Europe,” Forum for Ukrainian Studies, July 19, 2022, https://ukrainian-studies.ca/2022/07/19/explaining-the-westsplainers-can-a-western-scholar-be-an-authority-on-central-and-eastern-europe/.