This essay highlights the reconstruction of memory through material culture in Ukrainian museums since the 1990s. Within the context of the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, the Ivan Honchar Museum, and the Maidan Museum—all of which are in Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital—cultural workers have responded to politically salient events, including Ukrainian independence, the Maidan revolution, and the current war. This effort has included challenging Soviet–era historical narratives, engaging decolonial discourses, and centering culture suppressed under the Soviet regime. Although the current war is aimed at, among other things, destroying Ukrainian heritage and identity, both seem to have strengthened and deepened because of it.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, a new landscape, one created by those on the ground, has formed—public sculptures wrapped in plastic held in place by tape, monuments emerging from pyramids of sandbags, and churches engulfed in scaffolding. Ukrainian cities resemble installations by Christo (American, born Bulgaria, 1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude (American, born Morocco, 1935–2009). Meanwhile, museum workers and evacuation crews have moved artifacts from institutions and archives to undisclosed locations. Both newly formed initiatives and previously existing ones have allocated emergency supplies, like fire extinguishers and packing materials, to professionals in need.1See, for example, Polina Baitsym, “Art Workers at War: How the Ukrainian Artworld Has Rallied to Protect Cultural Heritage,” ArtReview, March 17, 2022, https://artreview.com/art-workers-at-war-how-the-ukrainian-artworld-has-rallied-to-protect-cultural-heritage/; and Simone Sondermann, “Im Fadenkreuz: Mit vereinten Kräften stemmt sich die Ukraine gegen die Zerstörung ihres Kulturerbes [. . .],” Weltkunst, May 4, 2022, https://www.weltkunst.de/kunstwissen/2022/05/ukraine-krieg-kulturerbe-unesco-im-fadenkreuz. Beyond the country’s infrastructure and human life, Ukrainian identity and statehood are under threat. In a recent essay, historian Timothy Snyder writes that Putin denies the very reality of Ukraine, and that his “claim that a nation does not exist is the rhetorical preparation for destroying it.”2Timothy Snyder, “The War in Ukraine Is a Colonial War,” New Yorker, April 28, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/essay/the-war-in-ukraine-is-a-colonial-war.

Attention is now very much focused on Ukrainian heritage, but museum professionals in the country have been working for the last several decades to preserve and/or recontextualize this same heritage. In defining narratives and frameworks for material culture, a pushback against Soviet and Russian legacies, which are often violent, is a common thread.

The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts in Kyiv holds the largest collection in Ukraine of European, Asian, and ancient art. The museum was founded in the early twentieth century by Bohdan (1848–1917) and Varvara Khanenko (1852–1922), however, the couple and their efforts were not publicly acknowledged until the 1990s, following the collapse and dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Ukrainian independence. The Khanenko Museum’s narrative has been shifting since then, and currently, discussions around decoloniality take place there. In March 2022, I spoke to Hanna Rudyk, Deputy Director General of Education and Communication.3Hanna Rudyk, interviews with author, March 11 and May 15, 2022. All information about the Khanenko Museum comes from these conversations. Rudyk, also a curator of the Islamic arts department, was in Lviv (where she moved to from Kyiv on the second day of the war). For security reasons, she could not reveal the current whereabouts of the collection.

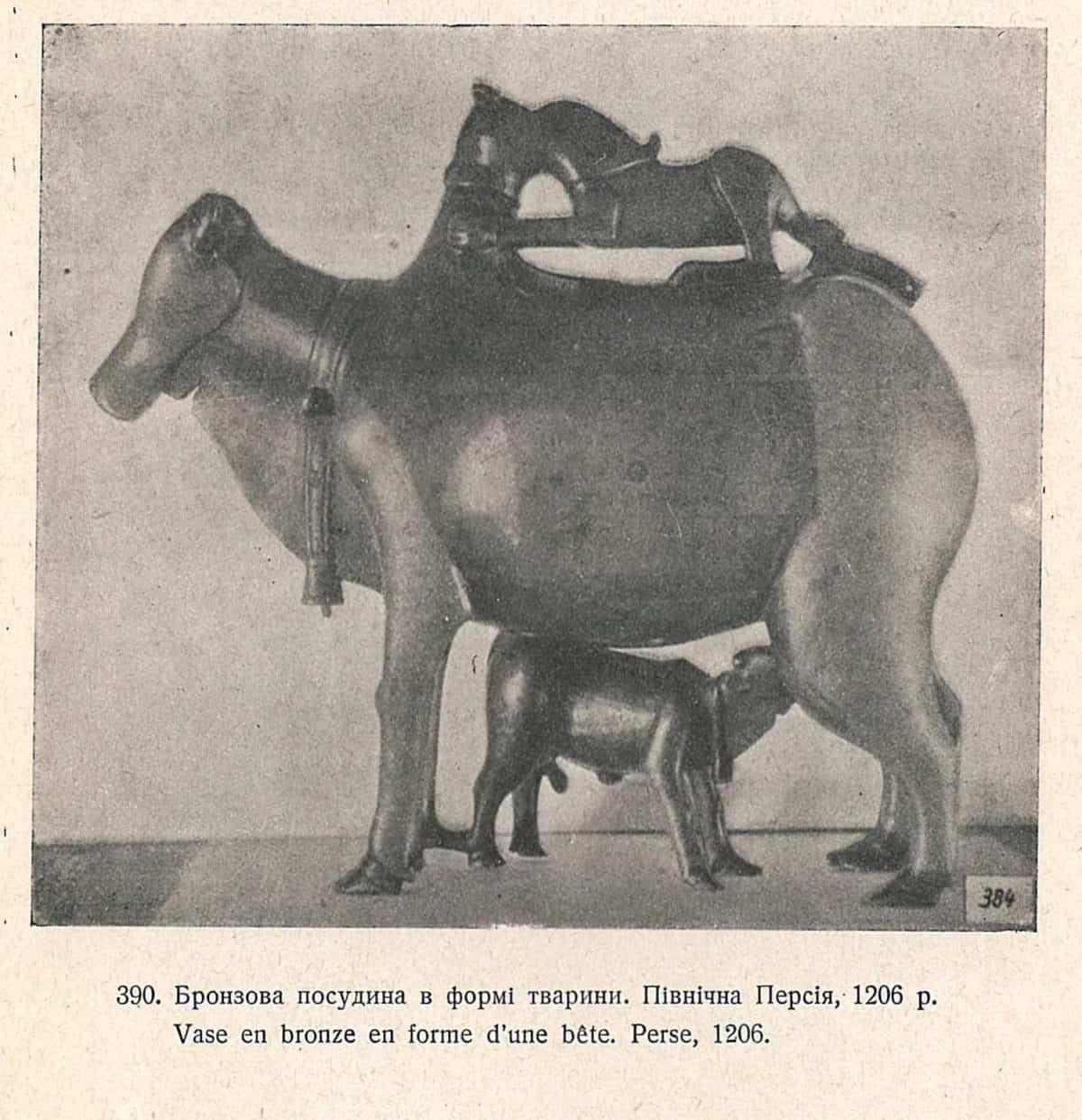

Rudyk told me that throughout the Soviet period and until 1999, the institution was called the Kyiv Museum of Western and Oriental Art. Under the Soviet regime, the original founders were considered “class enemies,” and mentioning or engaging with them was potentially dangerous for museum staff. Research into this history was launched in the 1990s, when historians working with the institution began reviewing its past from a Ukrainian, rather than Russian or Soviet perspective. They discovered that Varvara Khanenko donated the couple’s collection to the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in 1918 with the intention of creating a public museum. In 1919, however, under the Bolshevik regime, the museum became a property of the state, and its original collection was divided. Some rare items, such as a bronze Persian aquamanile in the form of a zebu cow with a calf and lion, made in 1206, were relocated to the Hermitage in the 1930s and remain there.4Information about the original collection is based on archival research by Hanna Rudyk and her colleagues at the Khanenko Museum. Interview with the author, May 15, 2022. The personal archives of the Khanenkos disappeared ten days following Varvara’s death in 1922, but researchers have been able to reconstruct this history based on limited documentation that is still available.

When I asked Rudyk if the current aim is to “Ukrainianize” the institution, she replied that the founders’ Ukrainian origins have emerged on their own. She does not consider the Khanenkos Ukrainian nationalists and sees their identities as more complex. They were, in fact, citizens of the Russian Empire. Bohdan was a member of the Empire’s State Council (Derzhavna rada), and both spoke mostly Russian (although likely understood Ukrainian). However, they supported the development of culture in Ukraine, and promoted the preservation of Ukrainian folk-art traditions, financed archaeological excavations in Ukraine, and created spaces for contemporary Ukrainian artists to work. They also funded medical, technological, and educational initiatives in Ukraine.

Rudyk and I talked again in May 2022. By this time, she had relocated to Berlin for a fellowship with the Museum of Islamic Art, where she is developing a project to decolonize the narratives of the Khanenko Museum. According to Rudyk, Ukraine has had a complex and multilayer experience of being both a colony of the Russian Empire and a semicolony of the Soviet Union, and yet historically, it was also connected to Western science and thought. She believes that as Western thought decolonizes, critiques, and deconstructs itself, it is important to rethink the place Ukraine occupied in the colonial past. She is considering, in particular, how Islamic and Buddhist art collections should be reframed. For example, exhibits traditionally separate the “Soviet East” from the “other East”—artificially cutting through a history of entanglement. This includes a divide placed between pre–Mongol Central Asian culture and Persian culture. Despite the historical connections, most exhibits follow the former borders of the Soviet Union. Similarly, the museum does not mention the colonial aspects of acquiring (and looting) that the Khanenkos implicitly, if not directly, engaged in by participating in networks of object circulation. For example, the couple bought illuminated pages torn from destroyed Islamic manuscripts, as at the time, images were valued more than handwritten lines.

Rudyk and her colleagues want to multiply the narratives surrounding objects and their provenance, stressing more than their aesthetic qualities, the focus on which is also a remnant of conservative Soviet curation. As she explained to me, “There are historical narratives being exhibited and others being silenced.” She has been thinking about this for a while, but the war pushed her to actualize the project. Though she refers to it as a “crisis decision,” she is hopeful that it will be fruitful. Ironically, in its attempt to erase Ukrainian identity, the Russian invasion, at least in this case, has furthered the critical possibilities of rereading Ukrainian history. Echoing other cultural workers and historians, Rudyk told me that “it’s very much a decolonizing war.”5For recent discussions on the topic of decolonization in relation to the Russian war against Ukraine, see Daria Badior, “Why We Need a Post-Colonial Lens to Look at Ukraine and Russia,” Hyperallergic, March 9, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/716264/why-we-need-a-post-colonial-lens-to-look-at-ukraine-and-russia/; Svitlana Biedarieva, “Decolonization and Disentanglement in Ukrainian Art,” post: notes on art in a global context, June 2, 2022, https://post.moma.org/decolonization-and-disentanglement-in-ukrainian-art/; Asia Bazdyrieva, “No Milk, No Love,” e-flux Journal, no. 127 (May 2022), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/127/465214/no-milk-no-love/; Kateryna Iakovlenko, “It’s Time for Ukraine to Speak,” apofenie, April 14, 2022, https://www.apofenie.com/letters-and-essays/2022/4/14/its-time-for-ukraine-to-speak; and Snyder, “The War in Ukraine is a Colonial War.”

Unlike the Khanenko Museum, which is working through its prerevolutionary and then Soviet history, some museums in Kyiv were established after independence, or in response to more recent political events. These institutions are nonetheless entwined with the Soviet Union or Russia, even if negatively. Take, for example, the Ivan Honchar Museum, also known as the National Center of Folk Culture, which opened in 1993 and is based on the art and ethnographic collection of Ivan Honchar (1911–1993), a dissident, collector, and artist.

Ihor Poshyvailo, the museum’s former deputy director, is currently in Ukraine.6Ihor Poshyvailo, correspondence via email with author, June 4, 2022. Information about the Ivan Honchar Museum and the Maidan Museum comes from this written exchange unless otherwise specified. We corresponded via email, and he told me that Honchar traveled across Ukraine after World War II to acquire objects, creating a personal museum in the late 1950s. This collection included folk paintings, icons, crafts, and clothing found in ruined churches or abandoned houses in the countryside. Honchar was not permitted to exhibit his collection. Indeed, the Soviet security apparatus—the KGB—surveilled his home, and visitors risked future “security issues.”7Ibid.

In some sense, this collection might be considered conservative, playing into the perspectives of right-leaning discourses on national identity, which favor “tradition” and the mythologies accompanying it. Poshyvailo, however, views Honchar’s efforts as a form of resistance. The types of items he saved were typically disregarded or even destroyed by the Soviet authorities, who were promoting socialist realism and its optimistic depictions of Soviet workers and life. Folk culture, meanwhile, was politicized by the Soviet regime and either banned or deliberately transformed.8Francine Hirsch, for example, writes about how the ethnographic department of the Russian Museum in Leningrad used Ukrainian folk culture to demonstrate backwardness or to identify class enemies. Hirsch states that this was done even though the museum’s ethnographers knew that the displays were not factual. See Francine Hirsch, “Getting to Know ‘The Peoples of the USSR’: Ethnographic Exhibits as Soviet Virtual Tourism, 1923–1934,” Slavic Review 62, no. 4 (Winter 2003): 683–709.

Poshyvailo also noted that folk art served as inspiration for Ukrainian modernist artists, although this relationship was also suppressed under the Soviet regime. Moreover, recent scholarship has pointed to the impact Ukrainian folk culture had on avant-garde artists—including well-known “Russian” figures from Kazimir Malevich (born Ukrainian region of the Russian Empire, 1878–1935) to David Burliuk (Ukrainian, 1882–1967), the father of “Russian” futurism. However, many figures associated with the Ukrainian avant-garde were subsumed into the Russian cultural canon, forced to flee, or killed.9See, for example, Bohdan Tokarsky, The Un/Executed Renaissance: Ukrainian Soviet Modernism and Its Legacies (Berlin: Forum Transregionale Studien e.V., 2021), https://doi.org/10.25360/01-2021-00016; and Myroslav Shkandrij, Avant-Garde Art in Ukraine, 1910–1930: Contested Memory (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2019). The work of many others, such as that of painter Maria Prymachenko (Ukrainian, 1909–1997), was exhibited as “naïve” art, downplaying its seriousness. Some of Prymachenko’s works were at the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, which burned to the ground after shelling by Russian forces on February 25, 2022. A museum guard and two residents removed what they could before the roof collapsed from the fire, and varying reports state that all or some of the Prymachenko collection was saved.10According to journalist Marina Mozol, it’s unclear if all or part of Prymachenko’s works were saved. Marina Mozol, “V nachale voiny iz goryashchego muzeya pod Kievom chudom spasli kartiny Marii Primachenko,” Meduza, June 15, 2022, https://meduza.io/feature/2022/06/15/v-nachale-voyny-iz-goryaschego-muzeya-pod-kievom-chudom-spasli-kartiny-marii-primachenko-teper-ee-raboty-stali-simvolom-borby-za-mir. On the Soviet treatment of Prymachenko’s art, see Baitsym, “Art Workers at War.” For the relationship between “naïve” art and female artists, see Iakovlenko, “It’s Time for Ukraine to Speak.” The output and achievements of female artists were particularly denigrated. Under Stalin, Ukrainian folk art was not only considered backward but also, as cultural researcher Kateryna Iakovlenko has recently written, “devoid of modernist traditions . . . perceived as different and opposed to the urban, intellectual, or progressive, that is, devoid of potential.”11Kateryna Iakovlenko, “It’s Time for Ukraine to Speak,” apofenie, April 14, 2022, https://www.apofenie.com/letters-and-essays/2022/4/14/its-time-for-ukraine-to-speak.

Beyond its efforts to reintegrate these relationships, the Honchar Museum aims to promote education and open communication, ideally creating an institution that serves the public as opposed to the authorities or outdated ideologies. Similarly, Rudyk considers disengaging with Soviet curatorial and educational practices as integral to the process of decolonization. In the Soviet Union, guides and other museum workers were expected to “enlighten” and “raise the masses” to the level of the intellectual “elite,” while nonetheless maintaining a demarcation between museumgoers and professionals. The education department was called “the mass department” and its activities “mass work,” because its audience was made up of the “human masses.” Rudyk sees this hierarchy as deeply non-democratic, as a top-down form of education in which museum visitors had no say.

In 2016, Poshyvailo became the director of the Maidan Museum. This institution is dedicated to Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan revolution, which resulted in the removal of pro-Russian Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. Though in some ways the two institutions are at opposite ends of the spectrum—the Honchar Museum preserves historical culture, whereas the Maidan Museum presents objects and themes connected to political and societal reorganization—both “were founded in a struggle for Ukraine’s freedom and out of the needs to tell the stories of who we are.”12Ihor Poshyvailo, correspondence via email with author, June 4, 2022. There are also links within their collections: artwork in the Honchar Museum is iterated in items held by the Maidan Museum—including in helmets and shields painted with flowers and other decorative elements, records of music and songs from the barricades, and the frame of an artificial yolka (Christmas tree) decorated with flags and posters.13For more on this relationship, see Laura Weber, “HISTORY OF THE NOW—a museum for Maidan. An Interview with Ihor Poshyvailo,” novinki-Blog, February 21, 2016, https://novinkiblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/14/history-of-the-now-a-museum-for-maidan-an-interview-with-ihor-poshyvailo/. For more information on the Maidan Museum’s collection, see “Museum collection,” National Memorial to the Heavenly Hundred Heroes and Revolution of Dignity Museum website, https://www.maidanmuseum.org/en/node/356. The Honchar Museum, meanwhile, after Maidan, began to collect stories and objects from recent history, and to organize events celebrating everyday life.14For more on the relationship between museum practices after Maidan, see Elżbieta Olzacka, “The Role of Museums in Creating National Community in Wartime Ukraine,” Nationalities Papers 49, no. 6 (2021): 1028–44, https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.39.

In a photograph accompanying an article published by the Guardian magazine in May 2022, Poshyvailo is shown holding a ceramic rooster obtained from a shelled kitchen in Borodianka, a city in the province of Kyiv.15Oliver Basciano, “‘We collect symbols of the resistance’: the Ukrainian museum working through the war,” Guardian, May 19, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2022/may/19/ukraine-maidan-museum-objects-ihor-poshyvailo-kyiv-cockerel. The rooster, images of which also made their rounds on social media, has become a symbol of Ukrainian resistance.16See, for example, @asiabazdyrieva, Instagram post, April 9, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CcJNmfMtxFz/. Poshyvailo and his team continue to collect other items as well, including white textiles used by fleeing people (who were later murdered) to show their civilian status, and children’s books and other belongings left in deserted apartments. He hopes to incorporate these items in future exhibitions.

The war leaves new material evidence of Ukrainian identity, fraught with destruction and Russian violence. The monuments and buildings covered with tarps or surrounded by sandbags, and collections moved to secret locations, are emblematic of what cultural critic Kateryna Botanova calls the “silence” of the war. As she writes in an article for Eurozine, “Ukrainian culture today is a void compiled of empty spaces that could have been filled with books, exhibitions and performances that did not happen.”17Kateryna Botanova, “Defined by silence: The Ukrainian art that was destroyed—and the art that never happened,” Eurozine, May 6, 2022, https://www.eurozine.com/defined-by-silence/. Historian Victoria Donovan, however, stresses the productive element of the current moment in Ukraine, noting: “As some things are being destroyed and disappearing—heritage, cities, people—other things are coming into existence. In the face of neo-colonial brutality, people are busy at work: desperation archiving, anger archiving, resistance archiving.”18Victoria Donovan, “Archives at War,” Tribune, April 26, 2022, https://tribunemag.co.uk/2022/04/archive-ukraine-russia-war-history-eastern-europe-mbembe. There are small signs of hope for the future of heritage.

In March, I called Milena Chorna, who was in Vinnytsia, a city in west-central Ukraine.19Milena Chorna, interview with author, March 18, 2022. Chorna is an art historian and heritage expert at the Ukrainian Cultural Fund. At the time we spoke, she was helping settle refugees, sewing camouflage nets, and working to promote heritage protection. Like Rudyk, she could not share specifics, but she did speak about general developments. In 2019 and 2020, she had traveled throughout Ukraine, encouraging regional representatives to apply for grants to preserve heritage. Everywhere she went, she found that people did not understand why they should restore things they didn’t see as “theirs.” Sites were viewed not as “Ukrainian,” but rather as belonging to other cultures—Polish or German, for example.

Chorna stressed that these sites are not only on Ukrainian territory, but also a testament to the complexity of Ukrainian identity. As she explained to me: “It’s our common cultural heritage. The monuments, the artifacts—they transmit history between generations.” But just a few years ago, people would not accept this perspective. Now, however, she sees signs of change. Since the war started, many people have contacted her to ask for help with protection and restoration, but this shift is bittersweet. Ironically, though Ukrainian heritage is now being recognized as important, it is in more danger. There is debate about whether blue shields—symbols used in crisis to identify property to be protected—should be put up. As Chorna noted, if Russian troops see a blue shield, they immediately know the monument is valuable, and so might destroy it more quickly.20Russians or Russian-backed separatists already destroyed or damaged museums and archaeological sites, including Crimean Tatar burial grounds, in Crimea and in the Donbas region of Ukraine before the current escalation. Some items were illegally removed to Russia to celebrate “Russian” cultural heritage. See Poshyvailo’s talk at the Smithsonian Institution’s symposium, “Current Approaches to the Conservation of Conflict-Affected Heritage”: Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, “Ihor Poshyvailo | Addressing the Conflict-Affected Heritage in Ukraine: Challenges and Responses,” YouTube video, May 12, 2020, 21:52, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l97dbr0rxgI&ab_channel=SmithsonianCulturalRescueInitiative.

Before the war, there was a long list of artifacts and sites needing restoration—and too few professionals to tend to all of them. Bureaucracy also stands in the way, as procedures in the current ministry of culture were passed down from the Soviet Union. Since independence, Chorna said, regardless of the president, culture has never been a priority. Rather, the weight of preserving Ukrainian heritage has been born by cultural workers, who earn little and don’t have much support. “But they manage to do great things,” she added. “They are fanatics really. They’re risking their lives now to save the artifacts.” She believes that the public attitude toward heritage preservation will have changed after the war because society will be readier for it.

These considerations resonate with Rudyk’s views. Soviet museums and those institutions in the tradition of them tended to be opaque about their shortcomings. Their hierarchical systems required long, positive reports, regardless of whether the findings were actually optimistic or in fact invented. Rudyk hopes for transparency. She wants displays to include objects in bad condition (unless being exhibited damages them further) in order to attract public attention to the fact that there is a problem.

It’s hard to say what new identities and conditions will emerge. Will heritage pluralize and expand what it means to be Ukrainian? Some developments are promising. We can hope that when the war is over, more complex and open narratives will form, transmitted through the heritage saved by those now risking their lives to do so.

- 1See, for example, Polina Baitsym, “Art Workers at War: How the Ukrainian Artworld Has Rallied to Protect Cultural Heritage,” ArtReview, March 17, 2022, https://artreview.com/art-workers-at-war-how-the-ukrainian-artworld-has-rallied-to-protect-cultural-heritage/; and Simone Sondermann, “Im Fadenkreuz: Mit vereinten Kräften stemmt sich die Ukraine gegen die Zerstörung ihres Kulturerbes [. . .],” Weltkunst, May 4, 2022, https://www.weltkunst.de/kunstwissen/2022/05/ukraine-krieg-kulturerbe-unesco-im-fadenkreuz.

- 2Timothy Snyder, “The War in Ukraine Is a Colonial War,” New Yorker, April 28, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/essay/the-war-in-ukraine-is-a-colonial-war.

- 3Hanna Rudyk, interviews with author, March 11 and May 15, 2022. All information about the Khanenko Museum comes from these conversations.

- 4Information about the original collection is based on archival research by Hanna Rudyk and her colleagues at the Khanenko Museum. Interview with the author, May 15, 2022.

- 5For recent discussions on the topic of decolonization in relation to the Russian war against Ukraine, see Daria Badior, “Why We Need a Post-Colonial Lens to Look at Ukraine and Russia,” Hyperallergic, March 9, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/716264/why-we-need-a-post-colonial-lens-to-look-at-ukraine-and-russia/; Svitlana Biedarieva, “Decolonization and Disentanglement in Ukrainian Art,” post: notes on art in a global context, June 2, 2022, https://post.moma.org/decolonization-and-disentanglement-in-ukrainian-art/; Asia Bazdyrieva, “No Milk, No Love,” e-flux Journal, no. 127 (May 2022), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/127/465214/no-milk-no-love/; Kateryna Iakovlenko, “It’s Time for Ukraine to Speak,” apofenie, April 14, 2022, https://www.apofenie.com/letters-and-essays/2022/4/14/its-time-for-ukraine-to-speak; and Snyder, “The War in Ukraine is a Colonial War.”

- 6Ihor Poshyvailo, correspondence via email with author, June 4, 2022. Information about the Ivan Honchar Museum and the Maidan Museum comes from this written exchange unless otherwise specified.

- 7Ibid.

- 8Francine Hirsch, for example, writes about how the ethnographic department of the Russian Museum in Leningrad used Ukrainian folk culture to demonstrate backwardness or to identify class enemies. Hirsch states that this was done even though the museum’s ethnographers knew that the displays were not factual. See Francine Hirsch, “Getting to Know ‘The Peoples of the USSR’: Ethnographic Exhibits as Soviet Virtual Tourism, 1923–1934,” Slavic Review 62, no. 4 (Winter 2003): 683–709.

- 9See, for example, Bohdan Tokarsky, The Un/Executed Renaissance: Ukrainian Soviet Modernism and Its Legacies (Berlin: Forum Transregionale Studien e.V., 2021), https://doi.org/10.25360/01-2021-00016; and Myroslav Shkandrij, Avant-Garde Art in Ukraine, 1910–1930: Contested Memory (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2019).

- 10According to journalist Marina Mozol, it’s unclear if all or part of Prymachenko’s works were saved. Marina Mozol, “V nachale voiny iz goryashchego muzeya pod Kievom chudom spasli kartiny Marii Primachenko,” Meduza, June 15, 2022, https://meduza.io/feature/2022/06/15/v-nachale-voyny-iz-goryaschego-muzeya-pod-kievom-chudom-spasli-kartiny-marii-primachenko-teper-ee-raboty-stali-simvolom-borby-za-mir. On the Soviet treatment of Prymachenko’s art, see Baitsym, “Art Workers at War.” For the relationship between “naïve” art and female artists, see Iakovlenko, “It’s Time for Ukraine to Speak.”

- 11Kateryna Iakovlenko, “It’s Time for Ukraine to Speak,” apofenie, April 14, 2022, https://www.apofenie.com/letters-and-essays/2022/4/14/its-time-for-ukraine-to-speak.

- 12Ihor Poshyvailo, correspondence via email with author, June 4, 2022.

- 13For more on this relationship, see Laura Weber, “HISTORY OF THE NOW—a museum for Maidan. An Interview with Ihor Poshyvailo,” novinki-Blog, February 21, 2016, https://novinkiblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/14/history-of-the-now-a-museum-for-maidan-an-interview-with-ihor-poshyvailo/. For more information on the Maidan Museum’s collection, see “Museum collection,” National Memorial to the Heavenly Hundred Heroes and Revolution of Dignity Museum website, https://www.maidanmuseum.org/en/node/356.

- 14For more on the relationship between museum practices after Maidan, see Elżbieta Olzacka, “The Role of Museums in Creating National Community in Wartime Ukraine,” Nationalities Papers 49, no. 6 (2021): 1028–44, https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.39.

- 15Oliver Basciano, “‘We collect symbols of the resistance’: the Ukrainian museum working through the war,” Guardian, May 19, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2022/may/19/ukraine-maidan-museum-objects-ihor-poshyvailo-kyiv-cockerel.

- 16See, for example, @asiabazdyrieva, Instagram post, April 9, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CcJNmfMtxFz/.

- 17Kateryna Botanova, “Defined by silence: The Ukrainian art that was destroyed—and the art that never happened,” Eurozine, May 6, 2022, https://www.eurozine.com/defined-by-silence/.

- 18Victoria Donovan, “Archives at War,” Tribune, April 26, 2022, https://tribunemag.co.uk/2022/04/archive-ukraine-russia-war-history-eastern-europe-mbembe.

- 19Milena Chorna, interview with author, March 18, 2022.

- 20Russians or Russian-backed separatists already destroyed or damaged museums and archaeological sites, including Crimean Tatar burial grounds, in Crimea and in the Donbas region of Ukraine before the current escalation. Some items were illegally removed to Russia to celebrate “Russian” cultural heritage. See Poshyvailo’s talk at the Smithsonian Institution’s symposium, “Current Approaches to the Conservation of Conflict-Affected Heritage”: Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, “Ihor Poshyvailo | Addressing the Conflict-Affected Heritage in Ukraine: Challenges and Responses,” YouTube video, May 12, 2020, 21:52, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l97dbr0rxgI&ab_channel=SmithsonianCulturalRescueInitiative.