This essay by feminist scholar and art curator Jana Kukaine explores the work of Latvian artist Daina Dagnija, who lived in exile in the United States after fleeing the Soviet occupation in 1944. While threading questions of migration and exile; memory, loss and belonging; and womanhood and mothering, Dagnija’s practice remains grounded in Baltic history, culture, and mythology. In her analysis of it, Kukaine establishes a potential convergence of Indigenous, anti-capitalist, intersectional feminist, and posthuman insights.

Daina Dagnija (1937–2019) is well-known in Latvia, especially after You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism opened in 2021 at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga. The exhibition title makes ironic reference to a remark that countless women artists are used to hearing—and that, though often presented as a compliment, in fact confirms the notion of masculine greatness as the decisive yardstick by which to evaluate art. The exhibition explored the diversity of Dagnija’s artistic interests and achievements, introducing a variety of feminist insights, including issues of gender stereotypes and related inequalities, at a time when, according to exhibition curator and art researcher Elita Ansone, “much prejudice and confusion [regarding feminism] remain among the Latvian public.”1Elita Ansone, “You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism,” press release, Latvian National Museum of Art, May 19, 2021, https://www.lnmm.lv/en/latvian-national-museum-of-art/exhibitions/you-paint-just-like-a-man-192. It is worth noting that this title marked the first time the word feminism had been used by the museum in the title of an exhibition, indicating a possible feminist awakening (or at least a thaw) in Latvia’s art scene.

Regardless of the prejudice and confusion surrounding the notion of feminism—and the distrust and anxiety with regard to it that is typical not only in Latvia but also in other post-socialist countries in Eastern and Central Europe—considering Dagnija’s work from a feminist perspective is rewarding. Indeed, taking into account the artist’s direct interaction with the political ideas and social activism of the so-called second wave of feminism and the women’s emancipation movement in the United States in the late 1960s and ’70s is not only theoretically gratifying but also historically informative. This association reveals a rarely acknowledged dimension of cultural exchange between the Latvian and American art scenes that, until now, has been mostly examined from the point of view of cross-cultural encounters via Latvian exile art circles—for example, the Hell’s Kitchen collective in New York, which Daina Dagnija was part of. Yet, accounting for the feminist sensibility in Dagnija’s works introduces a new dimension to transatlantic feminist genealogies as well as enhances intersectional feminist perspectives in Latvian art that are based in Eastern European cultural and political histories.

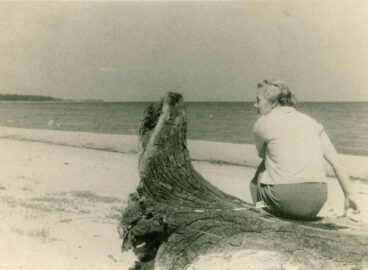

Daina Dagnija was born in 1937 in Riga. Four years later, in 1941, her family was affected by the atrocities of the communist regime when her cousins’ parents were deported to Siberia. Dagnija and her family fled the Soviet occupation in 1944, traveling to Gdansk in a cargo ship, and later to Germany, where they spent six years in the camps for displaced persons before moving to Detroit in 1951. In the following years, Dagnija studied art in New York and Los Angeles, and after a trip to Okinawa with her husband, she became immersed in the vibrant artistic and political activism and transformation taking place in the 1960s and ’70s in New York.

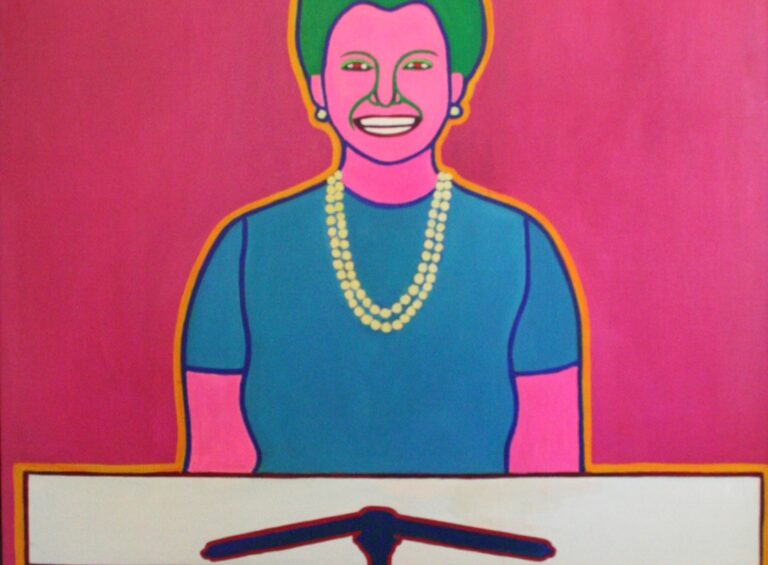

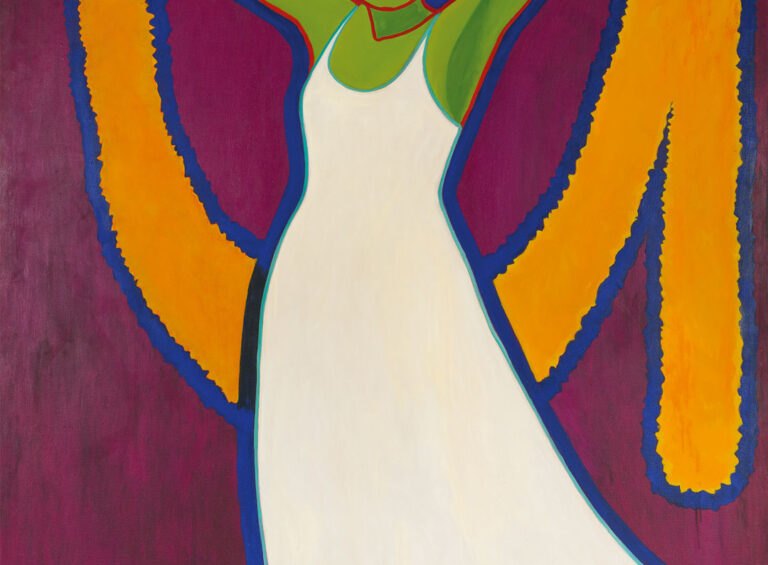

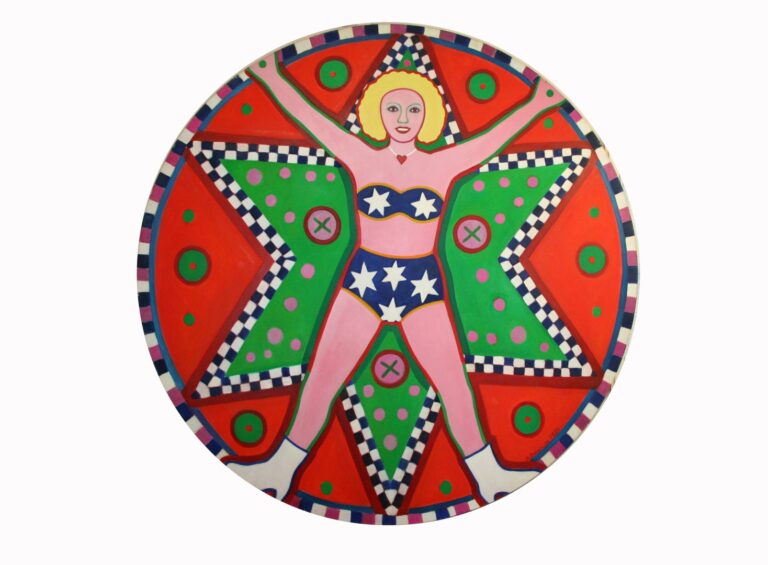

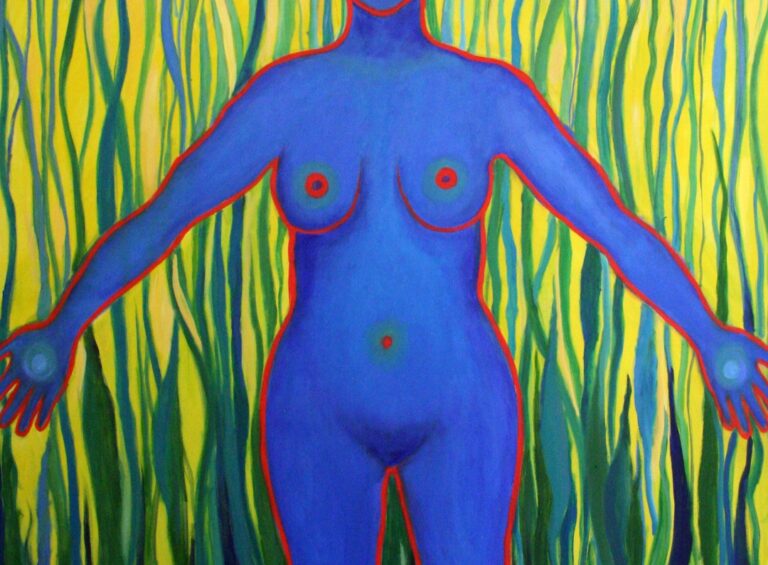

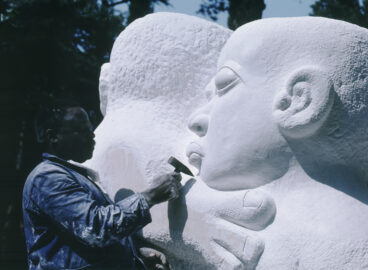

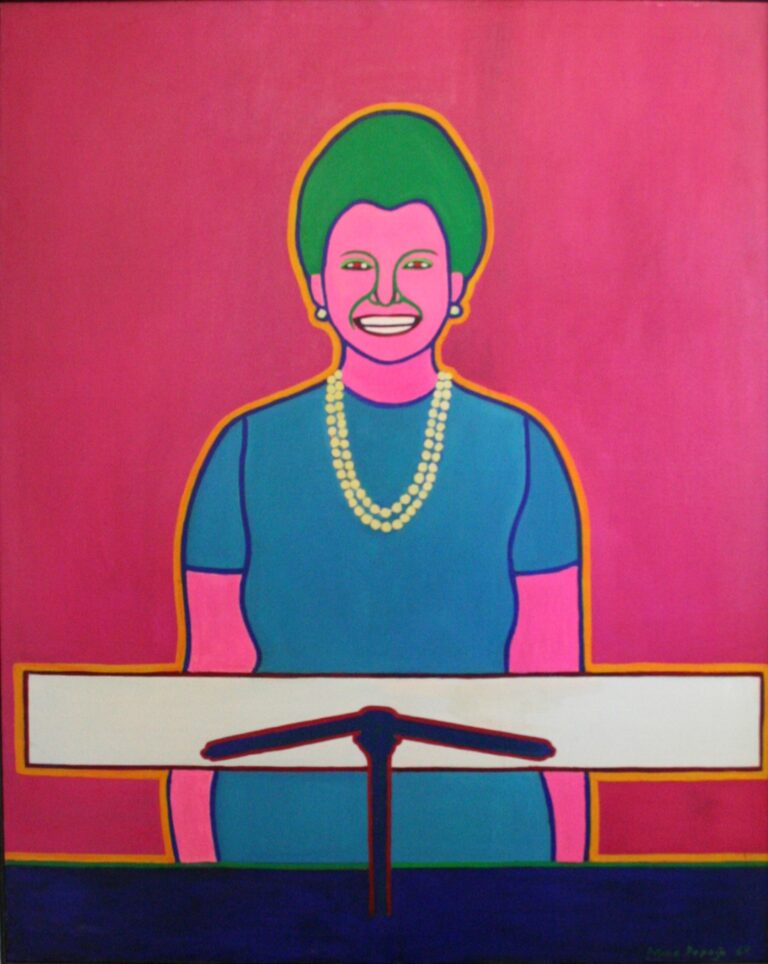

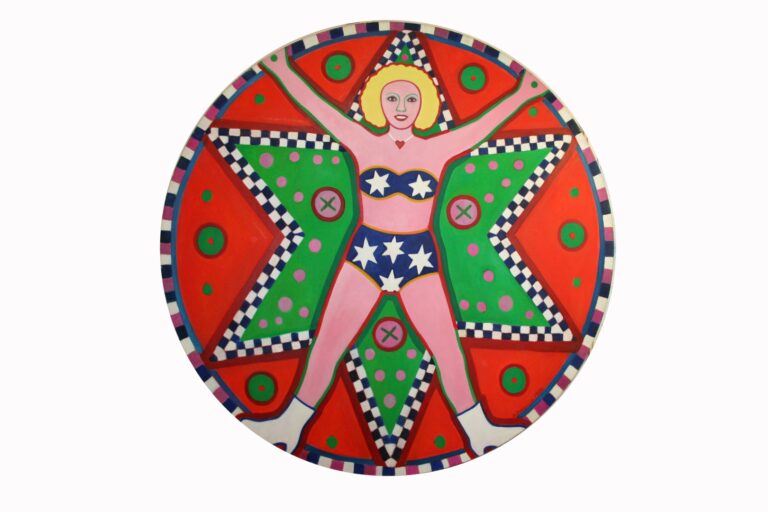

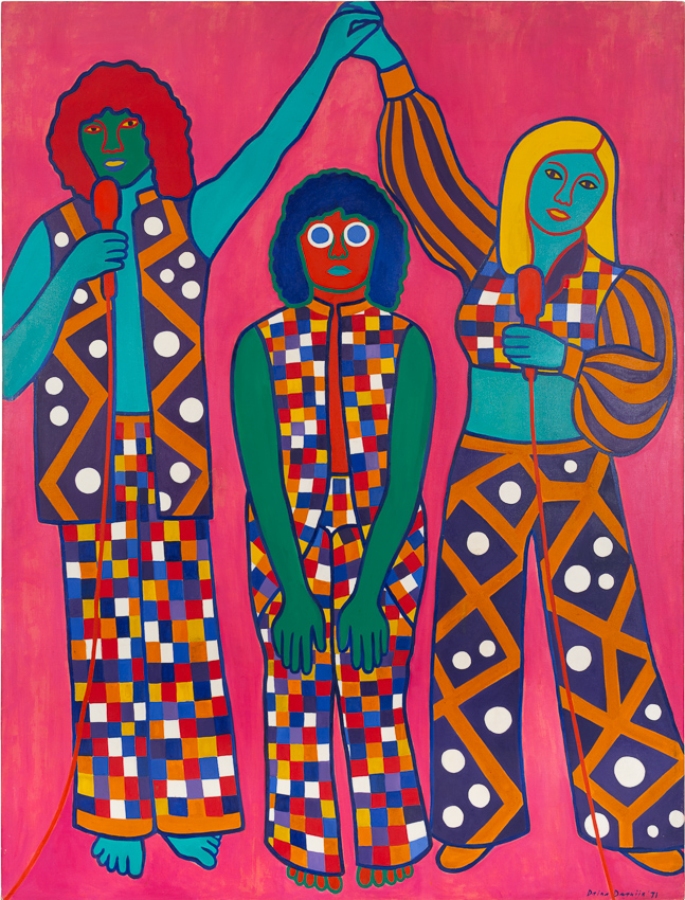

Numerous paintings undertaken by Dagnija during this period attest to her proximity to and involvement with the ideas and events associated with the women’s liberation movement (for example, Miss America 1922 and The Orator, both from 1969), and with antiwar and environmental activism (for example, Eartha Kitt from 1968 and Earth Day from 1971). Others reflect her interest in hippie subculture and popular culture (for example, Target Queen from 1980, Hair from 1971/72, and High Wire Performers from 1981). During this time, she developed what would later become her signature style—a form of figurative realism incorporating mainly human figures (often life-size depictions of women) rendered with thick, precise outlines against abstract backgrounds characterized by the application of intense complementary colors and elements associated with Pop and Op art.2Elita Ansone, “You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism,” in You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism, ed. Una Sedleniece and Rolands Krūmiņš, trans. Valts Miķelsons, exh. cat. (Rīga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2021), 8. Another hallmark of Dagnija’s style emerged early on in what is considered her “American period” (1968–2000), when she began depicting human bodies in green or blue, as if hinting at their nonhuman qualities.

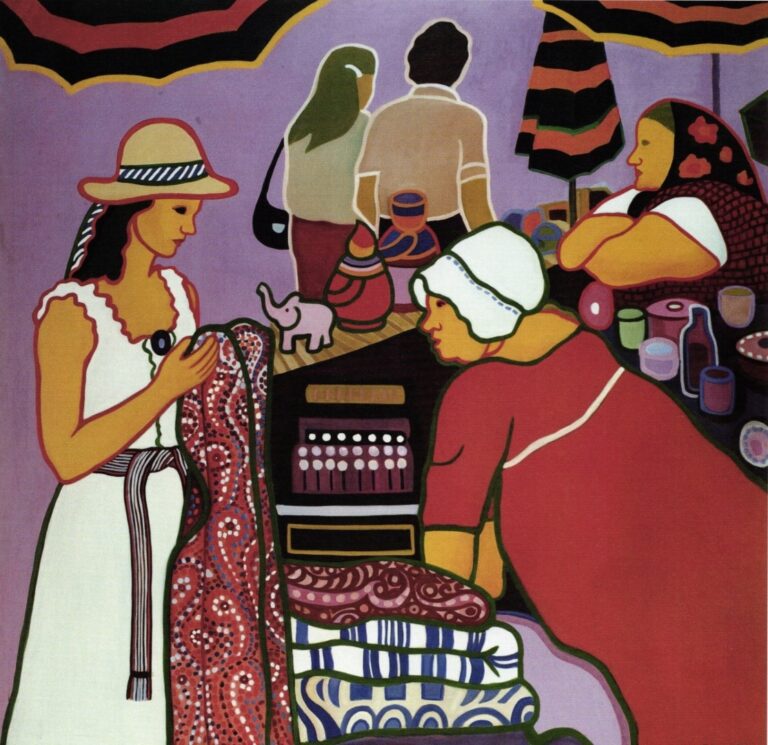

Despite her references to American life, Dagnija emphasized that she experienced the United States as an outsider. Though “doing her own thing” and “preoccupied with . . . existential and survival needs,” she learned to “live on the edge.”3Daina Dagnija, Milk Words, ed. Anita Vanaga and Daina Dagnija (Rīga: Neputns, 2004), 13. A hint of this edginess can be sensed in the painting Flea Market (1979), which depicts a woman looking at a pile of colorful blankets for sale in an open-air market. She is wearing a white dress that, as is characteristic of traditional Latvian folk costumes, is accessorized with a waist belt and pin, the latter recalling a sakta, or shirt brooch. In the market, among the many exotic, outdated, and vintage wares, she is perhaps looking for a sense of belonging and identity—or maybe recalling childhood memories and images or objects evoking life in Latvia prior to the Soviet occupation.

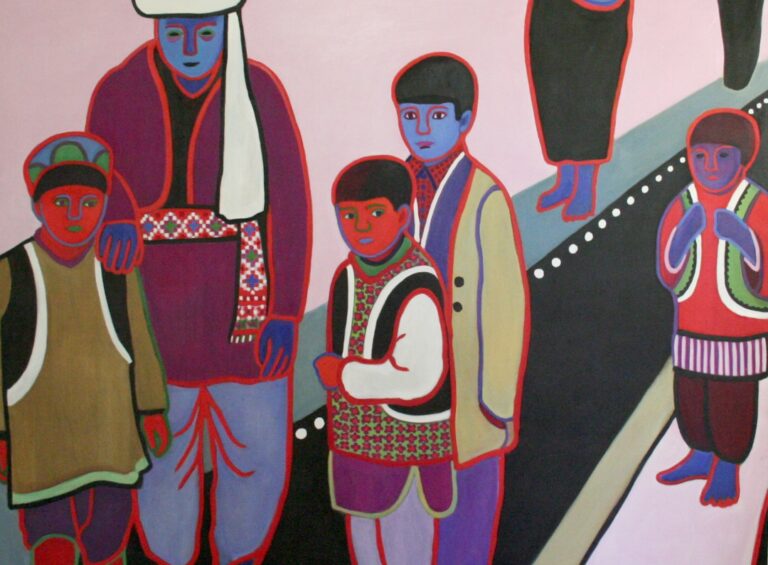

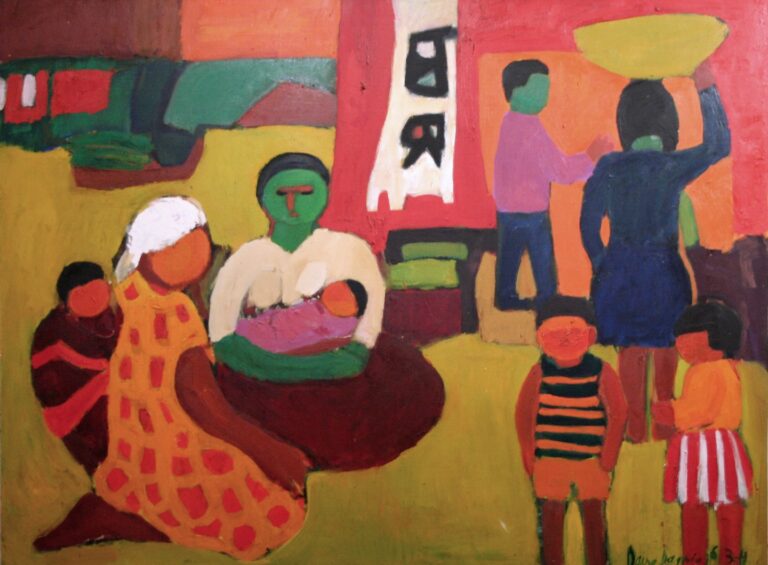

Dagnija expressed a much sharper and poignant sense of non-belonging, of being an outsider, in her multiple depictions of refugees. In her memoirs, the artist remembers that “since we had lost everything, I . . . learned not to worry about the material values or ‘security,’ which helped me to survive as an artist in the US.”4Dagnija, Milk Words, 12. Art historian and curator Andra Silapētere observes that the experience of exile was an important point of departure for Dagnija because the artist saw “parallels between her [own] story and those of refugees and marginalised communities in other parts of the world,”5Andra Silapētere, “DAINA DAGNIJA,” in PORTABLE LANDSCAPES: Comprehensive Latvian Exile and Emigrant Contemporary Art Project, exh. cat. (Berlin: K. Verlag, forthcoming [2023]). including the Latvian diaspora in the United States. While The Immigrants (1969) echoes her personal experience, Vietnamese Refugees (1976/77) and Afghan Refugees, also known as Where To (1980), address the casualties and loss caused by military conflicts incited by imperial powers in other parts of the world.

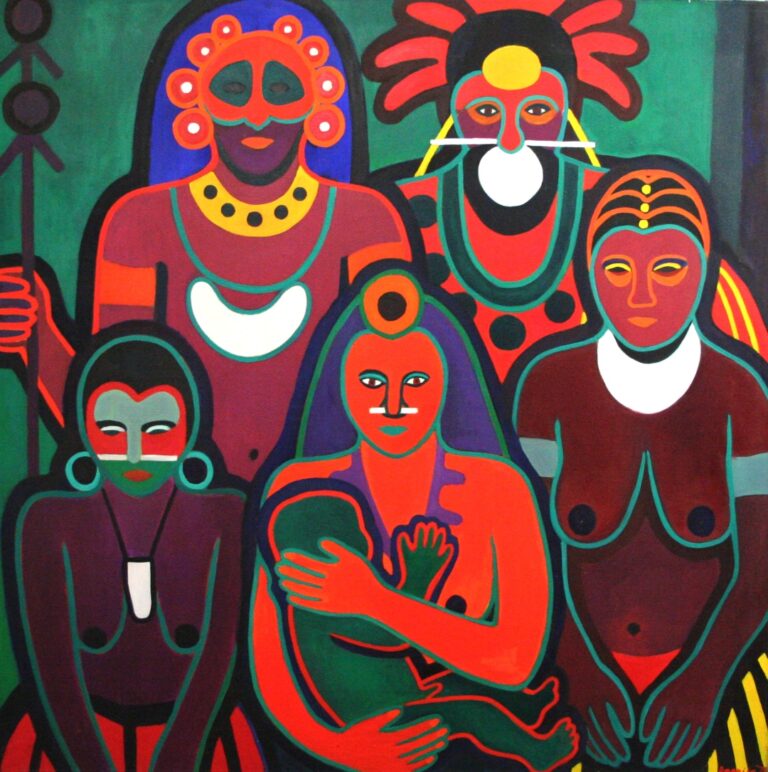

In these works, Dagnija emphasized the collective nature of displacement and flight—drawing attention to the fact that it is whole families and communities, not only individuals, who have been forced to flee. Despite their unusual and traditional appearance, the artist’s representations of migrants or culturally marginalized groups are never exoticized, nor do they celebrate “primitiveness.” Instead, her depictions of nomadic subjects6Rosi Braidotti,Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994). reveal a sense of “tender attunement”—an attitude “characterized by inclusivity, openness, commitment, and sensitivity”7Natalia Anna Michna, “From the Feminist Ethic of Care to Tender Attunement: Olga Tokarczuk’s Tenderness as a New Ethical and Aesthetic Imperative,” Arts 12, no. 3 (May 2023): 91, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030091; and Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London and New York: Verso, 2009). —that enhances their capacity to speak8Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (London: Macmillan, 1988), 271–313. and acknowledges their right to public mourning of lost homes and lives. Decades before the rights of Indigenous peoples had been officially recognized, Dagnija established an affective affinity for culturally, economically, and socially oppressed native communities. We can see this, for example, in Tribal Portrait (1975), or in works from the artist’s Okinawa period (1961–62), when she empathically explored the everyday life of the island’s inhabitants.

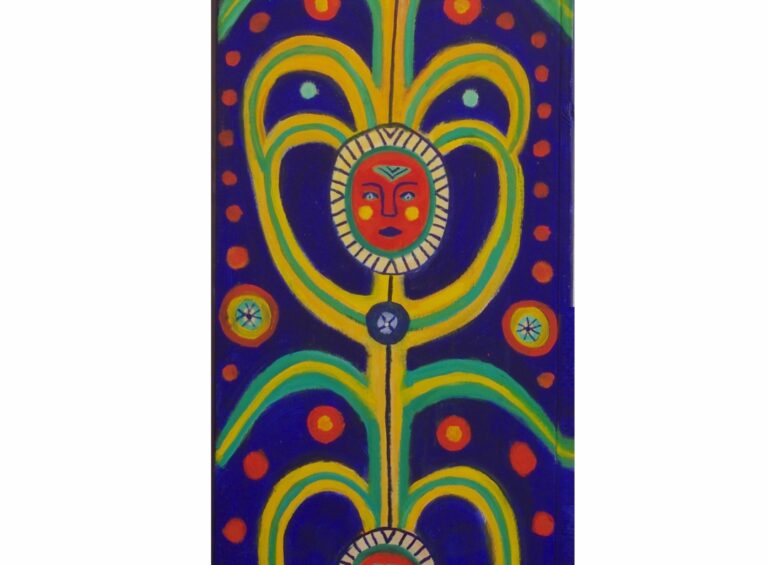

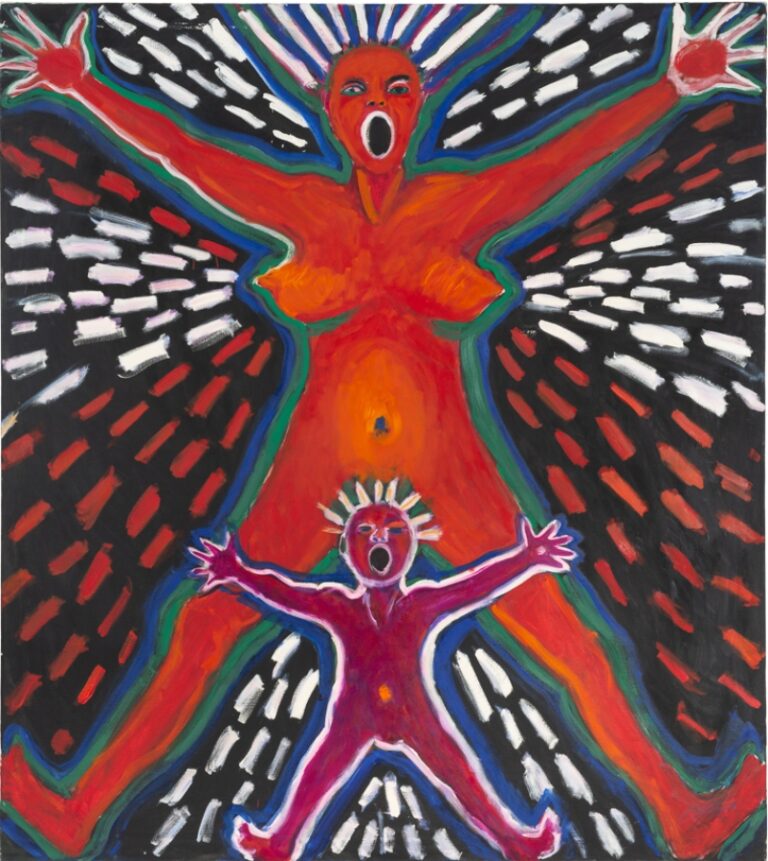

In her memoirs, the artist recalls that in refusing to identify with American consumer culture and fashions, or the US market economy, her thinking was “closer to that of Native Americans.”9Dagnija, Milk Words, 13. Moreover, turning to Indigenous cultures as alternatives to patriarchal consumer capitalism fostered her environmental awareness and nourished her interest in premodern societies, in their rites and beliefs, suggesting that a synthesis of matter and spirit, Indigenous wisdom and practices of art-making, can bring about new ways of being in the world.10Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 47. In particular, Dagnija focused on pantheistic religions, among them, the Goddess movement and its mythical notion of the Earth as a living organism. These perspectives are manifest especially in works from the late 1980s, when, for Dagnija, the female figure began to represent “a quasi-universal mandala, a kind of cosmos”11Ansone, “You Paint Just Like a Man!,” 14. in which myths and symbols of Native American, Baltic, Hindu, Greek, and other cultures interact and converge (for example, Woman Power and Lava from 1993, Nymph from 2008, Paris Painting No. 1 from 2009, and Family Tree from 2011).

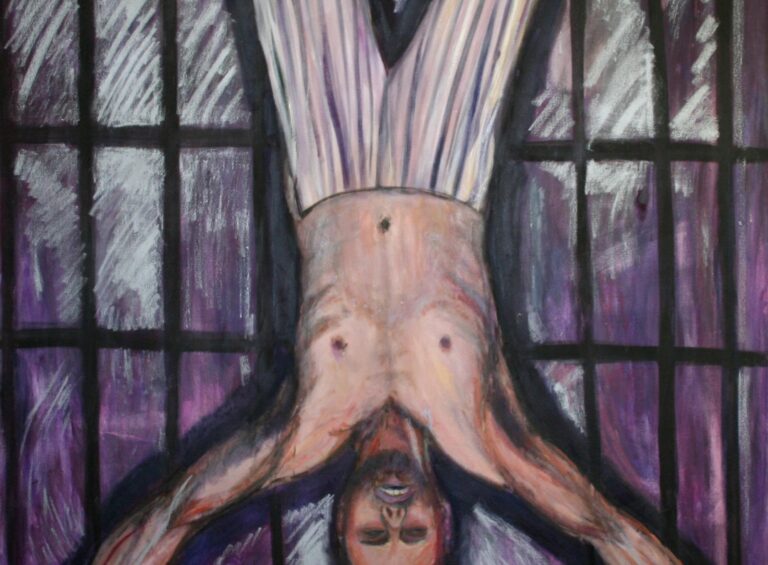

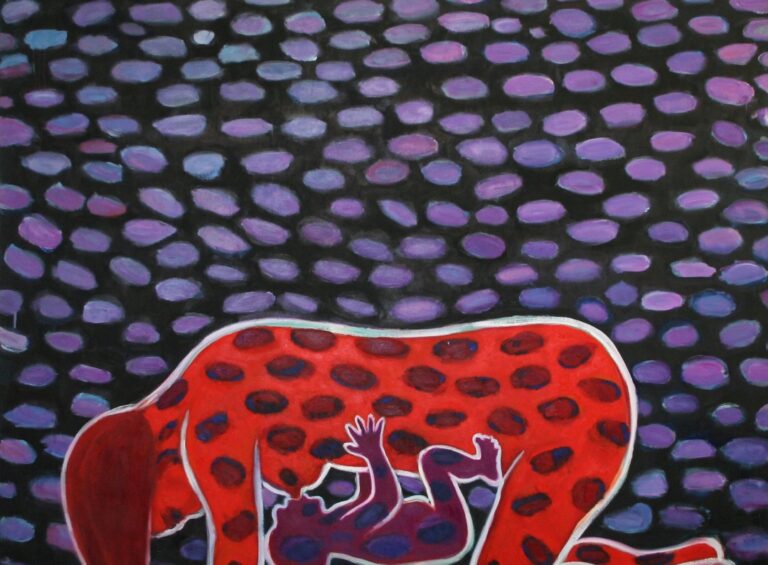

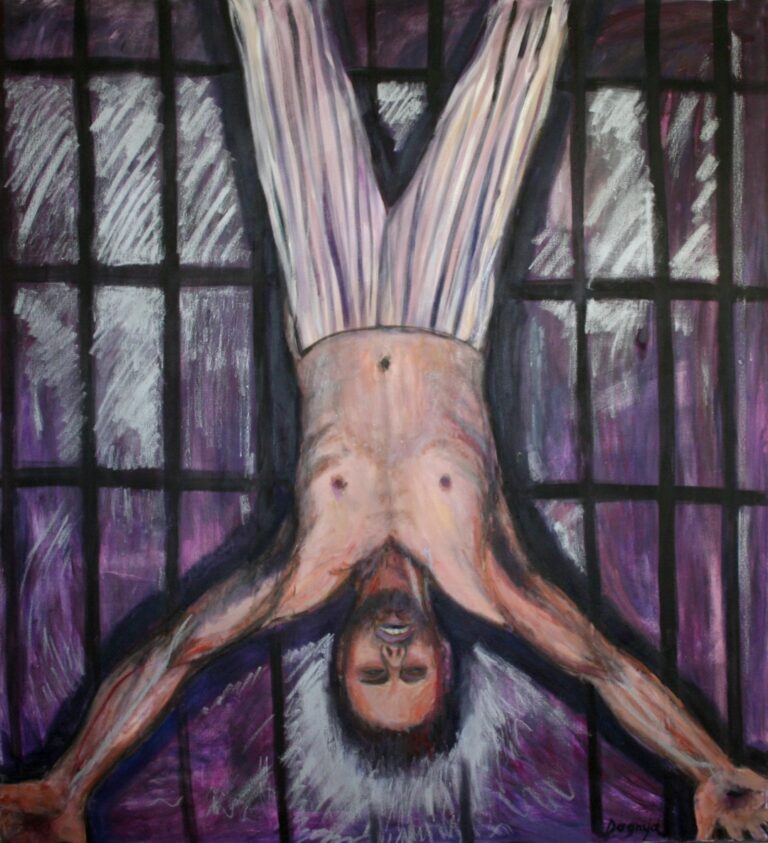

However, Dagnija’s artistic incentives nonetheless retained a political dimension, one eliciting the trauma of Soviet atrocities. The series Ancestor Lakes (1986–95), for example, not only evokes traditional Latvian folklore, mythology, and cosmogony but also speaks of the forgotten and silenced victims of totalitarian oppression. An even more poignant exposure of the horrors and crimes of the Communist regime is the Martyr series (1989). Among this body of work is a painting of a flipped female figure (reminiscent of an upside-down crucifix) fading into a snowstorm, which the artist dedicated “to the deported, who starved and froze in Siberia.”

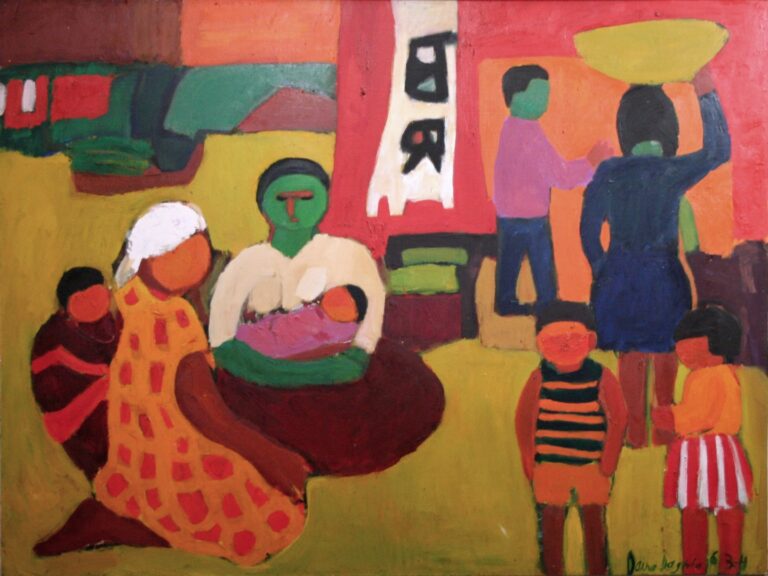

The nomadic wanderings of Dagnija’s subjects are also gendered. Dagnija returned to Latvia in 2001, and after her 2002 exhibition at the Museum of Foreign Art in Riga—now Art Museum Riga Bourse—she remarked that although some visitors had interpreted her works as related to Pop art, she actually had “little in common with the boys of ‘American’ Pop—I was European, an immigrant, a mother, [and] later—a divorced woman artist raising two sons by herself.”12Dagnija, Milk Words, 13. She frequently incorporated motifs of motherhood, especially in the 1970s and ’80s. Often disturbing depictions of pain, anxiety, and suffering, these images are characterized by an intense red and Neo-Expressionist aesthetic. Works like Scream (1986), Falling (1986), and The White Line (1987) expose maternal distress and vulnerabilities, and they resonate with a feminist critique of the commonly perceived disposability of female bodies and the appropriation of their reproductive functions for ideological purposes—as well as the double or even triple burden of a woman who is at once a mother, single parent, and artist.

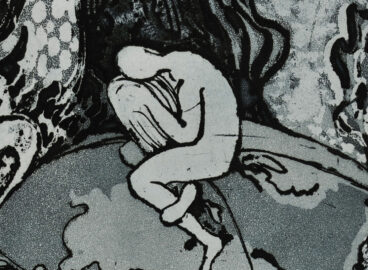

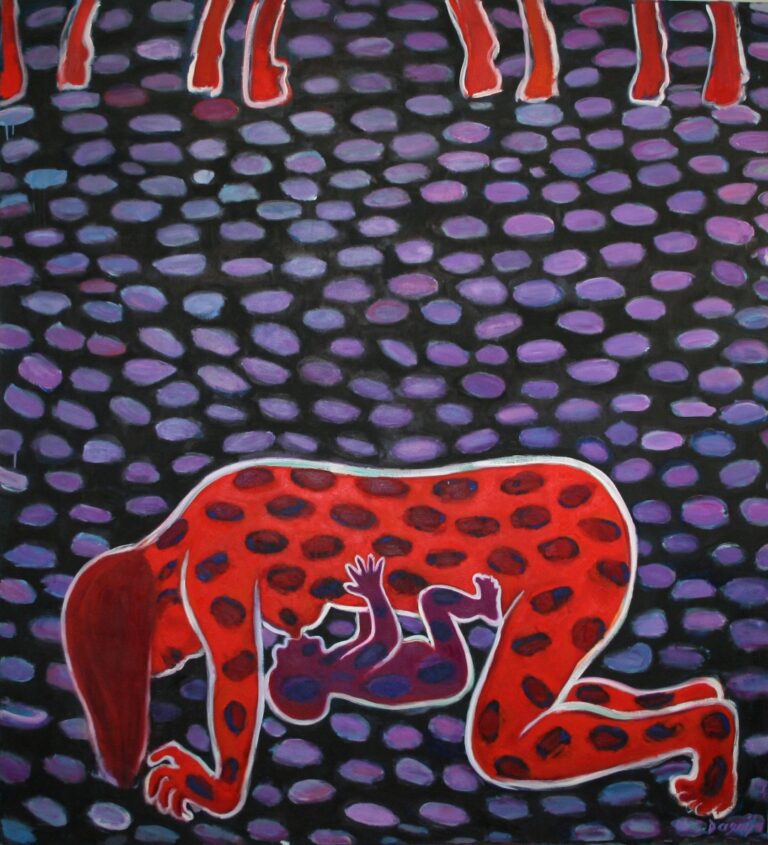

A more balanced view of mothering is represented in the series Woman and a Cow (1982–85), although the reference to pregnancy and the figure of an infant appear in only four of the fourteen paintings comprising it. According to art critic Aiga Dzalbe, the series might evoke associations with the myth of the Rape of Europa or the biblical story of the Flight into Egypt, or with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.13Aiga Dzalbe, “Dainas Dagnijas mītiskās domas atspulgs gleznās,” NRA, March 23, 2004. Yet it can also be read as a return to the meadow where Dagnija and her sister played as children. If in the painting Summer 1944 (1980) the two girls are disturbed by the military plane, in Woman and a Cow the threatening object is replaced by the cow – a nurturing, comforting, and life-bearing companion, a mother, and perhaps also a midwife. In this sequence of images, the woman and cow develop a post-human intimacy exemplified by their corporeal proximity and peaceful coexistence. The motif of a woman lying in the grass while a cow silently observes her recurs in several paintings and can be interpreted as an expression of the time necessary to overcome the pain of loss and the trauma of non-belonging. The process of gestation and birth and, in the final works in the series, the suckling of an infant, signify revival and a return to life, emphasizing the caring relationships, mutuality, and respectful coexistence evoked by the possibility of homemaking in a homeless world. The promise of a home is enabled by traversing the distinction between human and nonhuman, the self and the other, the caregiver and the cared for, the body and the spirit.

The nomadic subjectivity in Dagnijas’s works is saturated with her multicultural interests and experiences as a refugee, woman, mother, and artist. She has enriched and expanded the feminist ideas of the second wave with Indigenous wisdom and commitment to strive for the sustainable conviviality of species while reviving ancient views of cosmogony. Dagnija’s nomadic insights reflect the historical trauma of replacement and the social vulnerability of marginalized or oppressed communities. Her work addresses the mayhems caused by imperial powers, and it honors their victims while preserving hope for revival, rebirth, and reconstitution of life. The pain of loss combined with the joy of homemaking establishes a unique feminist sensibility in Latvian art—one that while nourished by feminist activism in the United States, remains grounded in Baltic history, culture, and mythology. The nomadic subjects in Dagnija’s work and the promise of finding a home remain important allies in the face of today’s political and social crises of fortifying imperial ambitions and reemerging forms of coloniality.

The author is grateful to Roland Krumins, Elita Ansone and Dace Ševica for their help with the visual materials.

- 1Elita Ansone, “You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism,” press release, Latvian National Museum of Art, May 19, 2021, https://www.lnmm.lv/en/latvian-national-museum-of-art/exhibitions/you-paint-just-like-a-man-192.

- 2Elita Ansone, “You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism,” in You Paint Just Like a Man! The Art of Daina Dagnija in the Context of Feminism, ed. Una Sedleniece and Rolands Krūmiņš, trans. Valts Miķelsons, exh. cat. (Rīga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2021), 8.

- 3Daina Dagnija, Milk Words, ed. Anita Vanaga and Daina Dagnija (Rīga: Neputns, 2004), 13.

- 4Dagnija, Milk Words, 12.

- 5Andra Silapētere, “DAINA DAGNIJA,” in PORTABLE LANDSCAPES: Comprehensive Latvian Exile and Emigrant Contemporary Art Project, exh. cat. (Berlin: K. Verlag, forthcoming [2023]).

- 6Rosi Braidotti,Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

- 7Natalia Anna Michna, “From the Feminist Ethic of Care to Tender Attunement: Olga Tokarczuk’s Tenderness as a New Ethical and Aesthetic Imperative,” Arts 12, no. 3 (May 2023): 91, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030091; and Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London and New York: Verso, 2009).

- 8Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (London: Macmillan, 1988), 271–313.

- 9Dagnija, Milk Words, 13.

- 10Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 47.

- 11Ansone, “You Paint Just Like a Man!,” 14.

- 12Dagnija, Milk Words, 13.

- 13Aiga Dzalbe, “Dainas Dagnijas mītiskās domas atspulgs gleznās,” NRA, March 23, 2004.