Refusing to fit into the mainstream art of her time, Gazbia Sirry replaced formal modernist training with local Egyptian art conventions to critically address women’s rights, patriarchy, social justice, and Western imperialism. A spokesperson for seventy years of Arab history, Sirry creates social realist mosaic-like paintings that still allow for a multiplicity of culturally loaded interpretations. Notwithstanding her celebrated use of color, her art continues to serve as an urgent and contemporary political act.

The canon of Egyptian art history has consistently championed women. Unlike their Western contemporaries, Egyptian women artists have been both present and on an equal footing with their male counterparts since the first Salon du Caire was held in 1921. As a result, a local industry of empowered women painters emerged during the last century.1A few examples of pioneer Egyptian female artists include Amy Nimr (1898–1974), Effat Naghi (1905–1994), Marguerite Nakhla (1908–1977), Khadiga Riaz (1914–1982), Tahia Halim (1919–2003), Zeinab Abdel Hamid (1919–2002), and Inji Efflatoun (1924–1989). Exposed to the outside world, they defied conventions, pioneered art movements, fought for women’s rights, and in the process, spoke on behalf of a nation. Gazbia Sirry (born 1925) is one of these groundbreaking women.

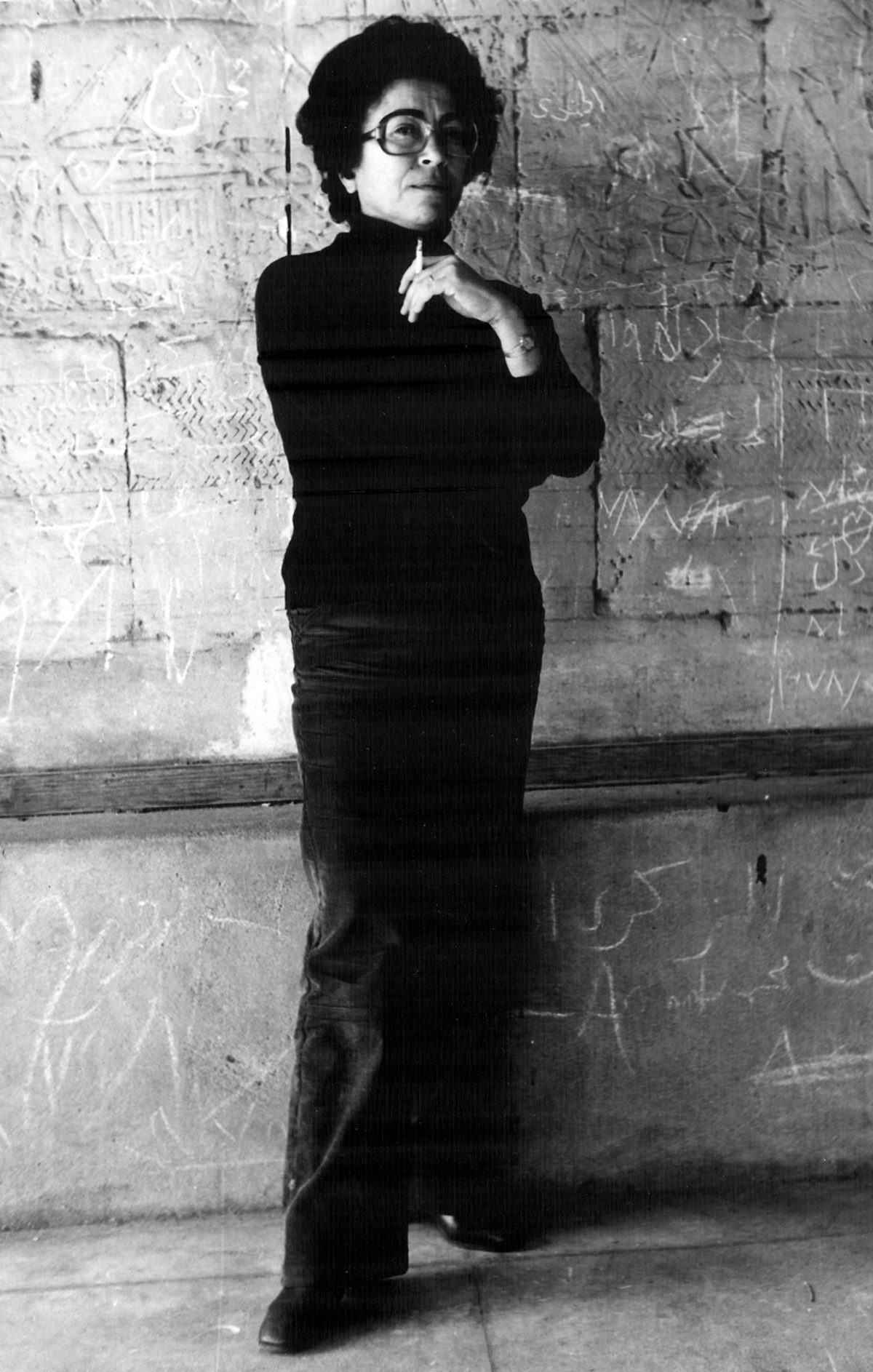

A spokesperson for seventy years of history, Sirry might well be looked upon as a complex political project.2Sirry lived through two kings, seven presidents, four wars, and three revolutions (1919, 1952 and 2011). Notwithstanding the historical significance of her art—and the international recognition that has come with a record of seventy-five-plus one-woman shows across continents—Sirry is surprisingly under-studied, and her art is described predominantly in technical terms centered on “color.”3The most recent institutional retrospective, titled The Lust for Color, was held at the American University in Cairo in 2014. See https://www.aucegypt.edu/news/stories/lust-color-exhibition-gazbia-sirry. The quintessence of life and political statements, however, seems to have been ignored, if not entirely missed. Educated in Egypt and Europe, Sirry built one of the most influential careers in twentieth-century modern Arab art.4Gazbia Sirry graduated from the Higher Institute of Fine Arts for Women Teachers in Cairo in 1948. In 1951, she traveled to France to study under French painter Marcel Gromaire (1892–1971). In 1954/55, she completed her postgraduate studies at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Divided into three overlapping phases, her paintings blur art and politics as they narrate the story of societies vacillating between triumph and defeat, dignity and humiliation, social justice and inequality. Sirry arguably birthed a new identity that makes no distinction between seeing and militancy. As she fluidly moved between styles, this “childless” grande dame became the national godmother to an entire nation (fig. 1).

Gazbia’s Voice: The Voice of a People

Much has been written about Gazbia Sirry’s “Lust for Color,” the title of the only monograph published about the artist, making “color” her legacy and the thread on which her entire career hangs.5Mursi Saad El-Din, Gazbia Sirry: Lust for Color (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1998). Although significant, color is but one facet of Sirry’s life and work. Since her appearance on the art scene in the late 1940s (fig. 2), she has opened a portal to Egyptian society in an effort to translate “the worries that plague [people].”6Nabil Farag, “al-Fanana al-Misriyyia Gazbia Sirry: al-Hawiyyia al-Kawmiyyia fi al-Muhit al-Alami,” al-Aklam 5 (May 1, 1985): 129–30. Decidedly figurative, then abstract expressionistic, her work is often denied the sociopolitical adumbrations she intended when she began her career by stripping the veil of intimate moments in open-end narratives. Often described as “ornamentation”7Aimé Azar, La peinture moderne en Égypte (Cairo: Les Éditions Nouvelles, 1961). or “Decorative Realism,”8Farouk Bassiouni, Gazbia Sirry, Description of Contemporary Egypt through Fine Arts (Cairo: al-Hay’a al-Ama l-il Isti’lamat, 1984), 18. Farouk Youssef, “The Rebellious Aristocrats,” al-Arab, September 23, 2018, 12. her early stylistic phase is a window onto an infinitely expandable world—and the foundation of her entire journey.

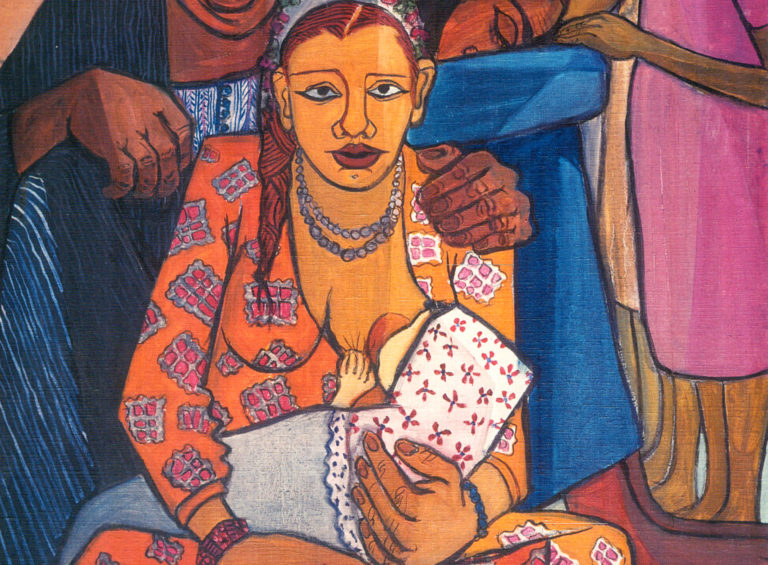

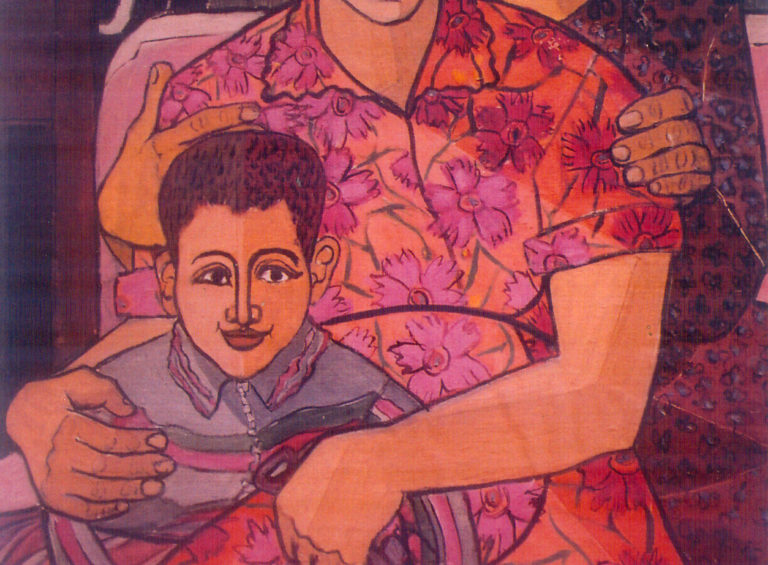

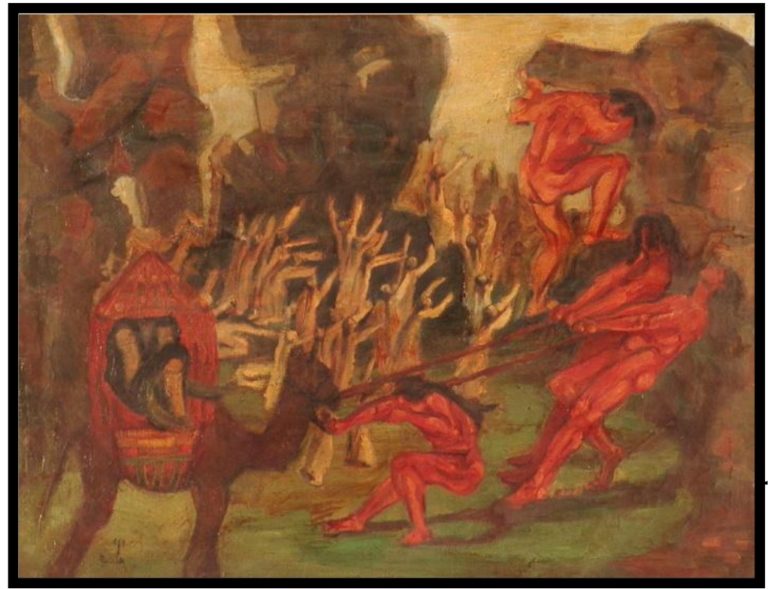

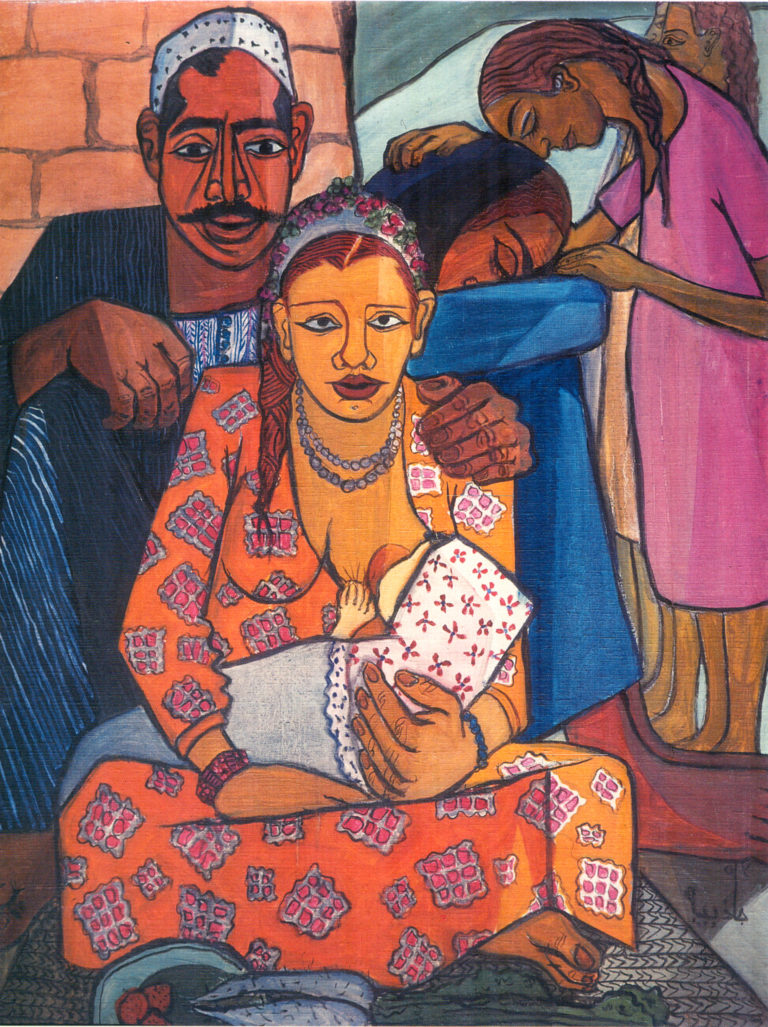

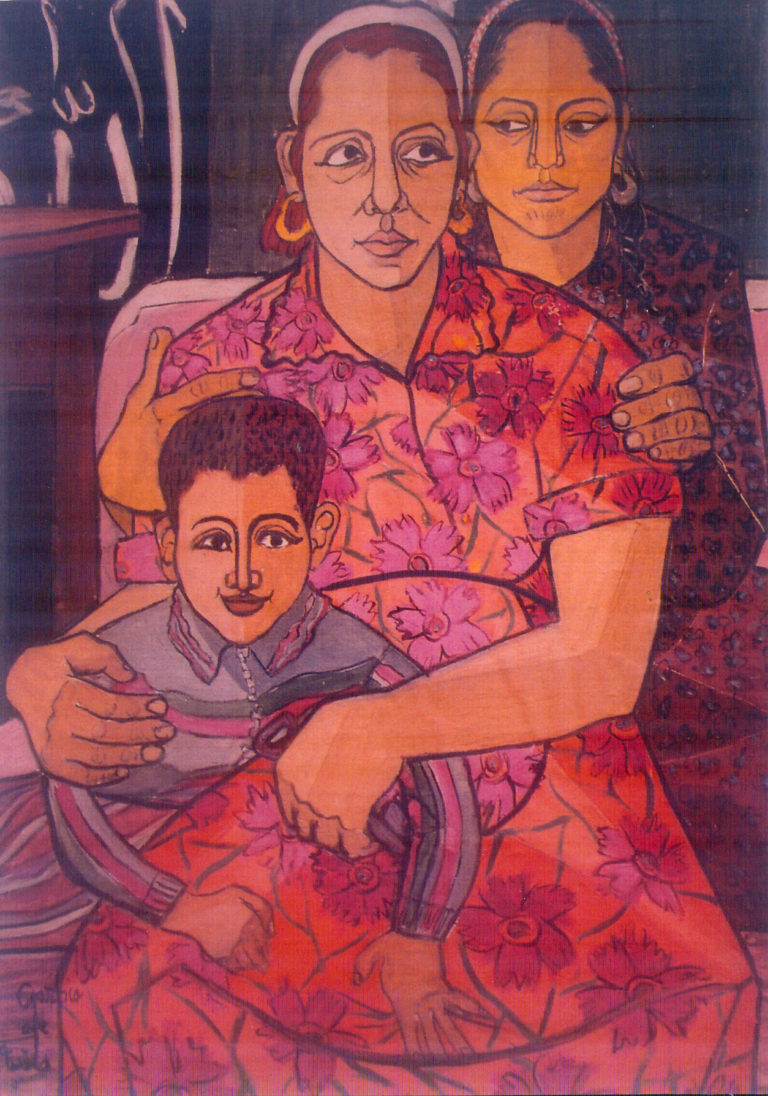

Raised by her widowed mother and divorced grandmother, Sirry was determined to address gender equality at a time when heated debates around the “Woman Question” peaked.9The formation of a feminist consciousness in Egypt ran in parallel to the country’s rapid development as a modern, secular state at the start of the 19th century. During the first half of the 20th century, women publicly demanded full social and political rights, which had been withheld in what has been a traditionally patriarchal society: specifically, they demanded access to equal education, and changes to the personal status law in terms of women’s rights in marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance, as it favored men over women. Female figures emerged as leaders of the Egyptian feminist movement, and ultimately, contributed to the transformation of women’s roles in Egyptian society between 1919 and 1952, known as the “liberal age.” For more, see Huda Shaarawi, Harem Years: The Memoirs of an Egyptian Feminist, 1879–1924 (New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1986). Filled with movement, resistance, and commotion, the extraordinary painting Tahrir al-Mara’a (Women’s Liberation; 1949) shows Sirry’s symbolism as she renounces the inherited traditions10Far-reaching and deeply enshrined patriarchal traditions forced women to adhere to domestic seclusion and gender segregation, limited their contact with men, and enforced the wearing of head scarves and face veils. that hold women back (fig. 3).11Reproduced from Nahir Ramadan al-Shoushany, “Women’s Issues as a Source for the Creativity of Female Artists in Modern and Contemporary Egyptian Art,” Egyptian Journal of Specialized Studies (EJOS) 6 (January 2018): 288. Three nude figures struggle to pull an immobile camel forward while carrying three veiled women inside a carriage shaped as a pyramid—a reminder of the tombs of the dead in ancient Egypt. On the top right, a muscular man wrestles a large stone as he tries to free the women’s path. In the middle of what could be a forest, humans shaped as trees raise their hands as they seek salvation. In al-Zawjatan (The Two Wives; 1953), Sirry touches on the controversial topic of polygamy (fig. 4). At the center of this image, the new wife sits on the floor, looking straight at the viewer. In her arms, a newborn baby boy is latched to her breast. The “expired” wife sits miserably behind her replacement. Grieving, the latter’s two teenage daughters console her as they feel responsible for their mother’s misfortune. By the same token, Sirry digs deeper into the ramifications of gender preference as she stresses favoritism toward the male child (Um Antar; 1953; fig. 5), or the perks of daughterhood’s associated domestic lifestyle of seclusion (Um Ratiba; 1952; fig. 6). In this series of paintings, Sirry calls upon the sacred light of ancient Egyptian temples, the rich colors of Coptic textiles, and the geometric themes of Islamic art. Playing with light and darkness, she repeats and juxtaposes vibrant motifs and patterns on walls, floors, and clothes. Consistent with Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor’s notion of “provincialized modernisms,”12See Okwui Enwezor’s notion in “Questionnaire: Enwezor,” October 139 (Fall 2009): 36. Sirry transforms the scenes into modern folkloric mosaics in which spatial disharmony and random precision meet.

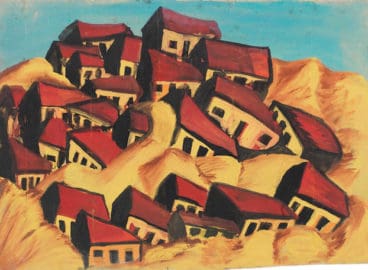

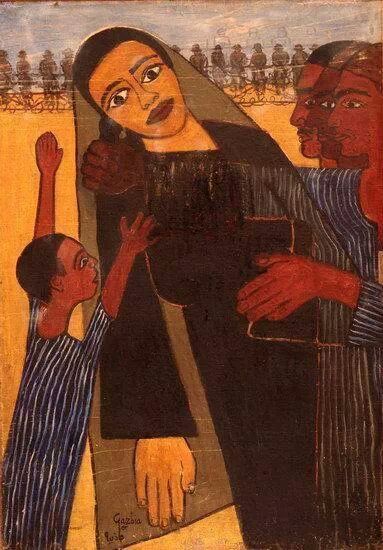

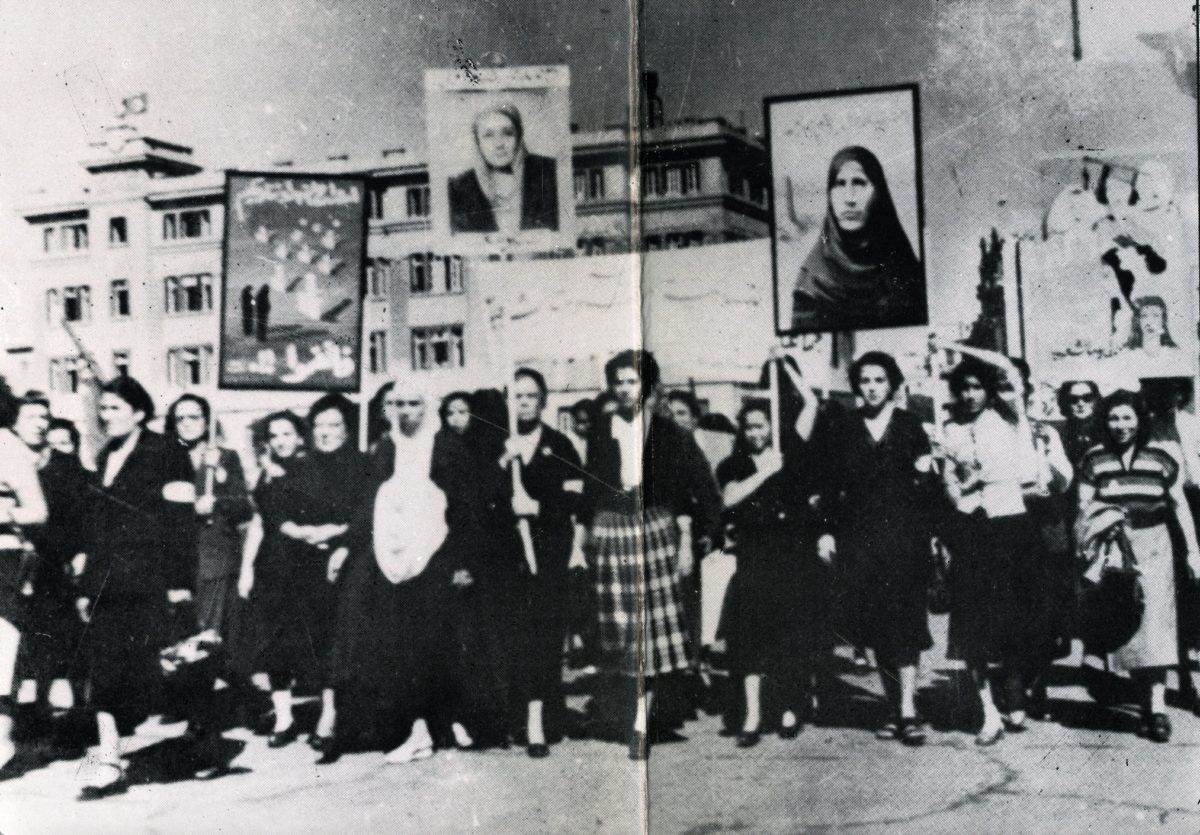

Unlike the majority of Sirry’s pattern-rich paintings of the 1950s, Umm Saber (1952; fig. 7), is composed of large monochromatic blocks. A tribute to one of the peasant women who sacrificed her life to resist British occupation in 1951 (fig. 8), the painting depicts a rural woman dressed in a traditional loose-fitting black gown (galabia).13Dubbed “The martyr of honor,” Fatma, also known as Umm Saber, was shot by British soldiers when she refused to be searched and physically touched by a British soldier at a checkpoint in Ismailia in November 1951. Abdel Hamid Rashed, “Umm Saber: The Martyr of Honour and Chastity,” al-Gomhuriaa al-Youm, August 19, 2017, https://algomhuriaalyoum.com/49221. Staring out at the viewer, her eyes are filled with fear and she is leaning backward. On the right, three men attempt to hold her before she collapses, while on the left, a young boy, probably her son, raises his tiny arms as he seeks to grab his mother’s attention. In the background, a dozen small figures dressed in similar uniforms and holding rifles stand behind barbed wire. A two-dimensional solid ground separates the soldiers from Umm Saber. Evocative of ancient Egyptian painting, the main figures are characterized by an absence of linear perspective, which results in a seemingly flat and static scene. Darker than the woman, the three men and the boy are shown in profile, their eyes drawn from a frontal view to infuse the surrealistic elements with Sirry’s ancient past.

Whereas a simple village woman illustrates Sirry’s treatment of oppression under British colonialism, two emancipated upper-class urban women represent the dawn of a new era. A tribute to the Revolution of July 23, 1952, and the overthrow of the Egyptian monarchy, Song of the Revolution, also painted in 1952, depicts two fashionably dressed women with strikingly short hair, gazing at the unknown (fig. 9). Rendered in horizontal shades of red, white, green, and black, the women’s clothes blend the colors of the old royal and the new liberation flags to symbolize the rite of passage. One woman plays the piano while the other is standing. Portrayed with a falcon face reminiscent of Horus, the emblem of the revolution, the standing woman places her birdlike hand firmly on the illegible music note, bare except for the word “nashid” (chant or anthem).

The Rupture

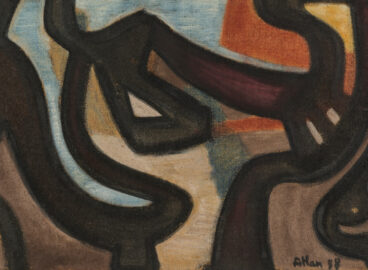

By 1959, Sirry was working in a new ideological and stylistic zone—revealing her private sphere in times of political instability. Two works serve to illuminate this period: Fortune Teller (1959) marks the break between representational painting and the beginning of the abstract period (fig. 10).14Farouk Bassiouni, Gazbia Sirry (Cairo: al-Hay’a al-Ama l-il Isti’lamat, 1984), 32. Whether by choice or destiny, Sirry never had children. Contextualized, she resorts to palmistry and folk culture to reflect on the future and the (im)probability of having a child. Meticulously constructed around the symbolism of colors developed in ancient Egypt, the face and belly of the central figure flaunt the blue color that routinely symbolizes fertility and rebirth.15For more on color symbolism in Ancient Egypt, see Richard H. Wilkinson, Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art (London: Thames and Hudson), 1994. The diamond-shaped belly button hints at the amulets used to protect the pregnant. While the yellow/gold face stands for the eternal, the choice of a striking red body indicates life and victory, and anger and fire. Facing the viewer, the central figure displays swollen breasts, a rounded belly, and possibly an embryo, cradled by a pale hand. The Arabic title of the painting Kare’at al-Kaf translates as The Palm Reader, which helps to explain why Sirry has chosen to highlight the hand. Rather than reading a coffee cup, or looking into a crystal ball, the artist spells out the method used to predict the future while evoking the protective talisman known as the Hand of Fatima. Heads in profile, the couple surrounding the central figure follow the conventional rule in ancient Egyptian art whereby the male figure is depicted with reddish-brown skin and the woman, here only the body, is light-skinned. In this context, Sirry’s choice to depict the face of the left female figure in black can be associated with rebirth and resurrection, as was the case with the god Osiris, who was returned to life by Isis. “By contrast,” as interpreted by Tiffany Floyd for the exhibition Post-War: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965, “the arms of the mud-red male figure on the right are crossed over his chest, a traditional burial pose, suggesting death.”16Tiffany Floyd, “Gazbia Sirry: The Fortune Teller,” Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 exhibition website, https://postwar.hausderkunst.de/en/artworks-artists/artworks/the-fortune-teller-die-wahrsagerin. Or the hopelessness of having a child. It is not clear who the central figure represents. Is it the palm reader or a self-portrait? Who is the naked couple? The artist and her husband? Highly rich in symbols and meanings, Fortune Teller is one of the artist’s most revelatory works as Sirry opens up a personal space and invites the viewer to partake in her own self-interrogation (fig. 11). Equally important, it stands at a crossroad between the desire to create a new life and the imprisonment of her husband, Adel Thabet, during the massive crackdown on leftist intellectuals by president Gamal Abdel Nasser (r. 1954–70).17Between January and April 1959, Gamal Abdel Nasser’s second wave of repression against communists began, and an estimated 700 to 1000 communists (specifically journalists and intellectuals) were arrested. Adel Thabet, Gazbia Sirry’s husband, was among them. Thabet spent thirty-three months in jail. For more on Nasser’s waves of repression, see Derek A. Ide, “Socialism without Socialists: Egyptian Marxists and the Nasserite State, 1952–65” (master’s thesis, University of Toledo, 2015).

In al-Sign or Awlad al-Takhshiba (Prison or Prison Children; 1959), Sirry depicts six figures trapped in the same cell (fig. 12). The figure on the top left is crying, while the one on the right looks to the side, wearing a prisoner’s number on his chest. Using sketchy brushstrokes, Sirry has distorted the prisoners, connecting them through yellow outlines, twisted facial features, and oblique angles. As we sense a reduction of unnecessary visual clutter, the prisoners are portrayed as shadows, laying open the simplicity of the subjects and conveying their blank resignation. Rather than juxtaposing colorful Islamic or Coptic geometric motifs, Sirry’s treatment of imprisonment evokes Pharaonic friezes found in tombs and temples. Chopped heads are arranged vertically on horizontal layers without linear perspective to reinforce the sinister and cramped atmosphere. Overtly simplified, the painting offers a counterpoint to the dazzling exuberance of the artist’s earlier works. Instead, it depicts a compressed and somber space, bare but for a yellow sun visible through the bars.

Al-Hazima (Defeat; 1967) concludes the radical break between Sirry’s figurative compositions and the beginning of her abstract period (fig. 13). The devastating moral aftermath of the 1967 Third Arab-Israeli War echoes in the inanimate painting as Sirry depicts herself standing firmly on the left. A shadow without clothes, she confronts the viewer. Functioning within a field that sways from Pan-Arab pride to shame, a landscape of ruin betrays the personal feelings of disillusionment. Behind the unshakable thousands-year-old gold pyramid appears a red patch, the sun. Is it setting or rising? It does not matter, as Sirry diligently points to the eternity of Egypt.

- 1A few examples of pioneer Egyptian female artists include Amy Nimr (1898–1974), Effat Naghi (1905–1994), Marguerite Nakhla (1908–1977), Khadiga Riaz (1914–1982), Tahia Halim (1919–2003), Zeinab Abdel Hamid (1919–2002), and Inji Efflatoun (1924–1989).

- 2Sirry lived through two kings, seven presidents, four wars, and three revolutions (1919, 1952 and 2011).

- 3The most recent institutional retrospective, titled The Lust for Color, was held at the American University in Cairo in 2014. See https://www.aucegypt.edu/news/stories/lust-color-exhibition-gazbia-sirry.

- 4Gazbia Sirry graduated from the Higher Institute of Fine Arts for Women Teachers in Cairo in 1948. In 1951, she traveled to France to study under French painter Marcel Gromaire (1892–1971). In 1954/55, she completed her postgraduate studies at the Slade School of Fine Art in London.

- 5Mursi Saad El-Din, Gazbia Sirry: Lust for Color (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1998).

- 6Nabil Farag, “al-Fanana al-Misriyyia Gazbia Sirry: al-Hawiyyia al-Kawmiyyia fi al-Muhit al-Alami,” al-Aklam 5 (May 1, 1985): 129–30.

- 7Aimé Azar, La peinture moderne en Égypte (Cairo: Les Éditions Nouvelles, 1961).

- 8Farouk Bassiouni, Gazbia Sirry, Description of Contemporary Egypt through Fine Arts (Cairo: al-Hay’a al-Ama l-il Isti’lamat, 1984), 18. Farouk Youssef, “The Rebellious Aristocrats,” al-Arab, September 23, 2018, 12.

- 9The formation of a feminist consciousness in Egypt ran in parallel to the country’s rapid development as a modern, secular state at the start of the 19th century. During the first half of the 20th century, women publicly demanded full social and political rights, which had been withheld in what has been a traditionally patriarchal society: specifically, they demanded access to equal education, and changes to the personal status law in terms of women’s rights in marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance, as it favored men over women. Female figures emerged as leaders of the Egyptian feminist movement, and ultimately, contributed to the transformation of women’s roles in Egyptian society between 1919 and 1952, known as the “liberal age.” For more, see Huda Shaarawi, Harem Years: The Memoirs of an Egyptian Feminist, 1879–1924 (New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1986).

- 10Far-reaching and deeply enshrined patriarchal traditions forced women to adhere to domestic seclusion and gender segregation, limited their contact with men, and enforced the wearing of head scarves and face veils.

- 11Reproduced from Nahir Ramadan al-Shoushany, “Women’s Issues as a Source for the Creativity of Female Artists in Modern and Contemporary Egyptian Art,” Egyptian Journal of Specialized Studies (EJOS) 6 (January 2018): 288.

- 12See Okwui Enwezor’s notion in “Questionnaire: Enwezor,” October 139 (Fall 2009): 36.

- 13Dubbed “The martyr of honor,” Fatma, also known as Umm Saber, was shot by British soldiers when she refused to be searched and physically touched by a British soldier at a checkpoint in Ismailia in November 1951. Abdel Hamid Rashed, “Umm Saber: The Martyr of Honour and Chastity,” al-Gomhuriaa al-Youm, August 19, 2017, https://algomhuriaalyoum.com/49221.

- 14Farouk Bassiouni, Gazbia Sirry (Cairo: al-Hay’a al-Ama l-il Isti’lamat, 1984), 32.

- 15For more on color symbolism in Ancient Egypt, see Richard H. Wilkinson, Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art (London: Thames and Hudson), 1994.

- 16Tiffany Floyd, “Gazbia Sirry: The Fortune Teller,” Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 exhibition website, https://postwar.hausderkunst.de/en/artworks-artists/artworks/the-fortune-teller-die-wahrsagerin.

- 17Between January and April 1959, Gamal Abdel Nasser’s second wave of repression against communists began, and an estimated 700 to 1000 communists (specifically journalists and intellectuals) were arrested. Adel Thabet, Gazbia Sirry’s husband, was among them. Thabet spent thirty-three months in jail. For more on Nasser’s waves of repression, see Derek A. Ide, “Socialism without Socialists: Egyptian Marxists and the Nasserite State, 1952–65” (master’s thesis, University of Toledo, 2015).