What is historicized, how is it recorded, and who determines and controls these seemingly unyielding criteria? Invoking multiple media apparatuses and deriving its title from a rumor, Akram Zaatari’s Letter to a Refusing Pilot (2013) undercuts the hegemonic and umbilical ties of media and history.

Akram Zaatari’s mixed-media installation Letter to a Refusing Pilot (2013) was first presented in the Lebanese Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. The pavilion was housed in one of the Arsenale’s warehouse-scale galleries. At one end, a large projection looped a thirty-five-minute digital video, while at the other, a 16mm film was projected onto a vertical slab rising from the floor. Oriented toward the latter was a single spotlighted cinema seat, which was upholstered in an inviting, deep red. Eight circular flat-topped stools were scattered around the space. Containing remnants of both the cinema house and the media gallery, the installation’s carefully conceived architecture signaled the breadth of Zaatari’s influences and references. Its construction and configuration drew on the history of cinema as well as the now widespread phenomenon of projection-based works made for gallery spaces, placing it within a genealogy of expanded media practices that marked a historical break from cinematic illusionism. In this brief text, I explore the installation’s citation of multiple media apparatuses and the conceptual implications of its archival and narrative engagements while contextualizing it within the trajectory of Zaatari’s artistic practice.

Arguably the core of the installation, the projected video opens with the whir of a motor and a blurry image that soon comes into focus, seemingly the feed from a camera attached to a drone that lifts off the tiled roof of a modernist building and rises well above what appears to be a Lebanese city, most likely Beirut or Saida. A series of disparate images and materials are presented one after another, including the opening pages of Le Petit Prince by Antoine Saint-Exupéry and photographs from the artist’s personal and family albums. The latter offer glimpses into Zaatari’s childhood years in Saida, where he spent a considerable amount of time in the gardens of the Saida Public Secondary School for Boys, which his father founded. The titular narrative of the “refusing pilot” involves an Israeli Air Force pilot who, during the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, defied orders to bomb a building in Saida that he recognized from the air as either a school or hospital. Another pilot sent to complete the mission bombed the school a few hours later. This anchoring story evades explicit narration until the very end of the video, though Zaatari offers clues and alludes to it through archival fragments and aerial views, images, and sounds.

Letter to a Refusing Pilot stages a negotiation between rumor, memory, evidence, and the archive, revealing a tenuous and temporally extended process of revisiting and reconstructing a past that has consistently evaded official historical record and is increasingly being reinterpreted and represented through imaginative acts of artistic mediation. Zaatari’s installation needs to be read in tandem with the larger body of work he has produced since the 1990s, which engages questions of materiality, methods of assembly, and modes of display while working with archival media and documentary forms. Zaatari studied architecture in Beirut and media studies in New York before returning to Lebanon and working for a television network (Future TV) owned by former Lebanese prime minister Rafiq Hariri, who was assassinated in 2005.1For more on Zaatari’s biography, see Mark Westmoreland, “You Cannot Partition Desire: Akram Zaatari’s Creative Motivations,” in Akram Zaatari: The Uneasy Subject, ed. Juan Vicente Aliaga (León: MUSAC; Mexico City: MUAC; Milan: Charta, 2011). This early engagement with television significantly shaped his thinking and artistic formation. In the context of an early work All Is Well on the Border Front (1997), Zaatari discusses the case of Lebanese resistance fighters and former political prisoners whose accounts were often manipulated and broadcast on television as pictures of patriotic heroism that entirely ignore the enormous psychological and physical damage inflicted upon their subjects.2A synopsis of All Is Well on the Border Front (1997) reads: “Three staged testimonies shed light on the experiences of Lebanese prisoners held in Israeli detention centers during the occupation of South Lebanon. Notions such as heroism and suffering are explored amid a dissection of the codes of representation and ideological indoctrination during times of conflict in this tribute to Jean-Luc Godard’s Ici et ailleurs.” Karl Bassil and Akram Zaatari, eds., Earth of Endless Secrets (Frankfurt am Main: Portikus; Beirut and Hamburg: Sfeir-Semler Gallery; Beirut: Beirut Art Center, 2009), 7.

Born in 1966, Zaatari grew up in a middle-class family in the southern Lebanese city of Saida while it was under Israeli occupation. He was sixteen and already a keen photographer when the Israeli invasion of 1982 took place. Standing on the balcony of his family’s apartment, he recorded the sounds of fighter planes flying overhead, and photographed smoke rising from the hillsides surrounding his hometown as Israeli bombs struck. A selection from this series of photographs, which he plucked from his personal albums, was composited to create Saida June 6, 1982 (2006), a work that depicts numerous explosions around Saida over an extended period of time in a single frame. These photographs were then transferred onto 16mm film to create the filmic component in Letter to a Refusing Pilot. In the projected video across the gallery, other materials from Zaatari’s personal archive appear, including a text entry from his brother’s diary, dated July 2, 1982, which, accompanied by a newspaper cutout of an image of an Israeli jet, reads, “Today my father took us to visit the school, which was damaged during an airstrike, and Akram took a few pictures.”3Akram Zaatari et al., The Pavilion of Lebanon at the “55. Esposizione Internationale d’Arte—La Biennale di Venezia,” exh. brochure, 2013. In the video’s closing moments, an Israeli news broadcaster tells of the bombings of Ain El-Hilweh camp, a stronghold of the Palestinian resistance located adjacent to the school.

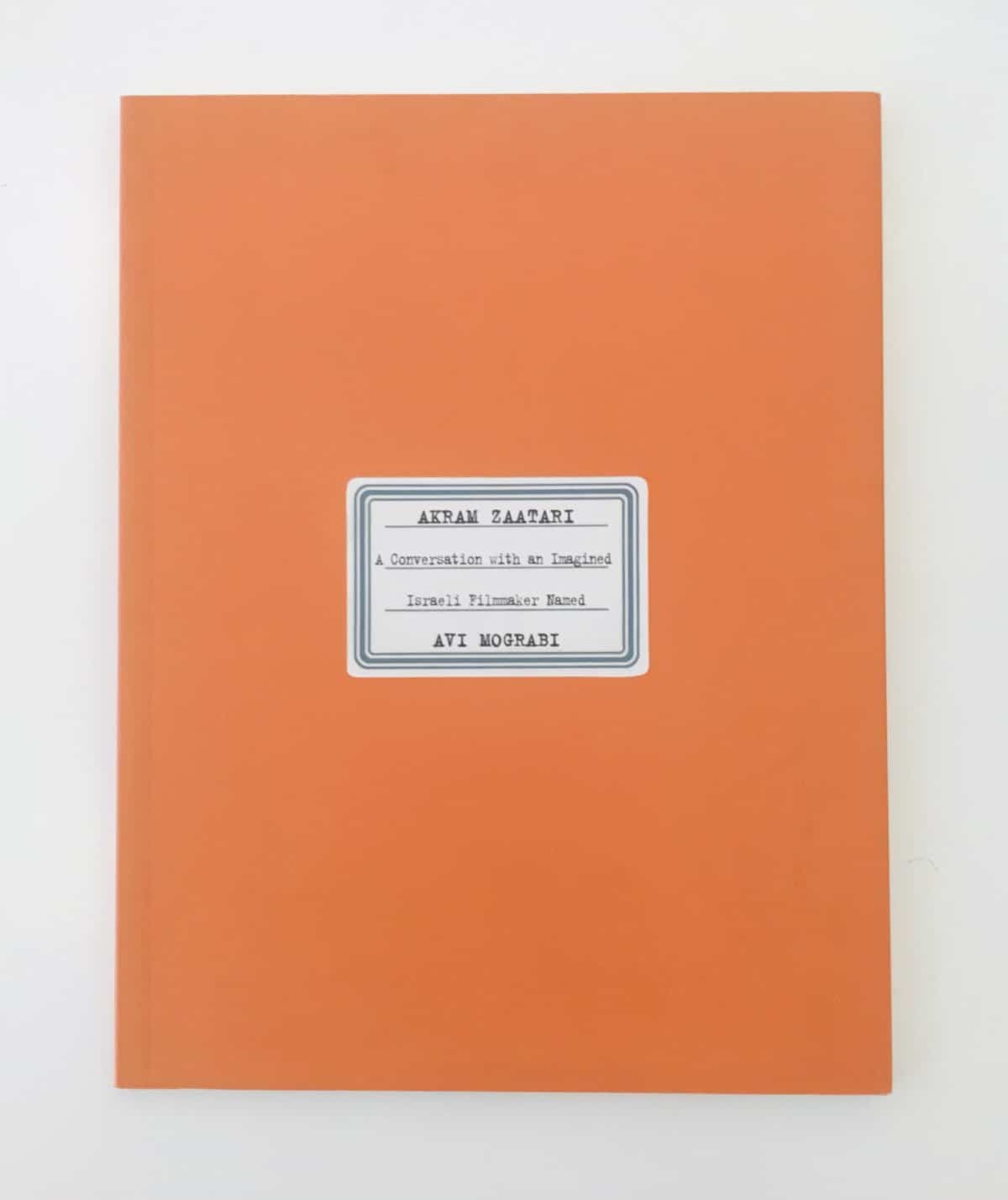

Zaatari grew up with various versions of the refusing pilot’s story. He recalls hearing from his uncle of a former Lebanese Jew turned Israeli pilot who had attended school in Saida and refused to bomb his alma mater, instead dropping the explosives into the sea. In fact, the school was bombed, purportedly by another pilot sent to complete the mission abandoned by his colleague. Yet the rumor—a touching tale of wartime empathy, childhood attachment, and a somewhat naïve expression of peaceful coexistence in the Levant—persisted. Zaatari recounts the tale in A Conversation with an Imagined Israeli Filmmaker Named Avi Mograbi (2010–12), the published script of a staged public conversation between him and Mograbi, two real filmmakers assuming fictional identities in a bid to overcome the seeming impossibility (both logistical and conceptual) of conversing openly across enemy lines.4Akram Zaatari, Akram Zaatari: A Conversation with an Imagined Israeli Filmmaker Named Avi Mograbi (Aubervilliers, France: Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers; Paris and San Francisco: Kadist Art Foundation; Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 30. Seth Anziska, then a doctoral candidate in International History at Columbia University conducting research on the 1982 occupation, found himself flipping through the pages of Zaatari’s new book at the Arab Image Foundation, an organization co-founded by the artist in 1997 that seeks to, “collect, preserve and study photographs from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab diaspora.”5See “About the Arab Image Foundation,” Arab Image Foundation website, http://arabimagefoundation.org/getEntityFront?page=PageDetails&entityName=PageEntity&idEntity=1. The Foundation has, since its establishment, amassed a collection of more than six hundred thousand photographs drawn from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Egypt, Morocco, Iraq, Iran, Mexico, Argentina, and Senegal. Zaatari’s involvement in its activities has changed significantly following the first decade (he is no longer a member) in response to his thinking around the medium of photography, collecting, preservation, and the creation of large, centralized, physical archives in a time when technology allows for both the easy creation and proliferation of visual documents (still and moving) as well as their preservation through digital means. For more on this, see Akram Zaatari, “Interview by Eva Respini and Ana Janevski,” Projects 100, April 2013, https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/projects/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Interview-Akram-Zaatari1.pdf. As he reached the section where Zaatari mentions his uncle’s telling of the refusing pilot story, Anziska was immediately reminded of a research interview he had conducted in Jaffa, Israel, two years before.6Zaatari et al., The Pavilion of Lebanon at the “55. Esposizione Internationale d’Arte – La Biennale di Venezia.” The subject was an architect named Hagai Tamir—a pilot in the Israeli Air Force during the bombing campaign in question—who told of his own refusal to carry out a mission when he recognized (based on his professional training) that the target was a school. Stripping the rumor of the flourishes it had acquired during the course of its decades-long circulation, including the pilot’s Lebanese Jewish heritage and personal attachment to the school in question, it matched Tamir’s telling perfectly, setting off a chain of events that connected Zaatari to Tamir and catalyzed the making of Letter to a Refusing Pilot.

The multimedia work’s reference to both cinema history and the capabilities of digital video are palpable and deliberate, specifically a combination of montage and editing techniques that allows multiple views and times to be compressed and displayed in a single frame. The lone cinema seat, the whirring projector, and the grainy images from Zaatari’s personal archive–deliberately transferred to 16mm film–evoke the cinematic apparatus, while occupying a larger installation that moves away from nostalgia and commemoration toward an incisive inquiry into the image itself. An influential figure in this regard, and a recurring reference for Zaatari, is French-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard (born 1930), whose ambitious Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–98) is a fitting culmination to a practice that has straddled both film and video, traversing the traditionally distinct genres of narrative, avant-garde, and documentary.7Jean-Luc Godard. Histoire(s) du cinéma. 1988–98. DVD: 266 minutes. Chicago: Olive Films, 2011. See also Mark Nash, “Art and Cinema: Some Critical Reflections,” in Art and the Moving Image, ed. Tanya Leighton (London: Tate Publishing, 2008), 448–49. Godard’s 2004 film Notre Musique explicitly addresses questions of violence and its cinematic representation, making reference to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the following terms: “In 1948, the Israelites walked in the water towards the Promised Land. The Palestinians walked in the water to drown. Shot and reverse shot. Shot and reverse shot. The Jewish people join fiction. The Palestinian people, the documentary.”8Jean-Luc Godard. Notre Musique. 2004. DVD: 80 minutes. New York: Wellspring Media, 2005.

Godard uses the language of mainstream commercial film editing to compare the historical fates of two peoples affected by a state of constant conflict. Ultimately, fiction is the idiom of victors and documentary that of the oppressed. Overturning this hierarchy, a political gesture in its own right, is where Zaatari and Godard intersect. In Zaatari’s work, the coalescence—of private and public, records from both sides of the border, mainstream media accounts, the archives of the Arab Image Foundation, personal photographs, recollections, and possessions—and the corresponding subversion of victor and victim archetypes are orchestrated through mixed-media constructions that engage in historical speculation and perform an archaeology of rumor, one that has only recently been verified as fact.

On a related note, the negotiation between analog and digital formats, in the contexts of storage, preservation, and use, finds some reflection in Zaatari’s changing view of the role, priorities, and modus operandi of the Arab Image Foundation. A decade ago, he proposed that the Foundation digitize its collection and then return the photographs to the contexts they originally inhabited (a family album, a bedroom wall), where they may ultimately meet their end.9In a 2013 interview with MoMA curators Eva Respini and Ana Janevski, Zaatari stated, “It would be interesting to determine what exactly is essential to preserve. If emotions can be preserved with pictures, then maybe returning a picture to the album from which it was taken, to the bedroom where it was found, to the configuration it once belonged to, would constitute an act of preservation in its most radical form.” See Zaatari, “Akram Zaatari: Interview by Eva Respini and Ana Janevski.” This proposal, rejected by the Foundation’s current members, reflects a preoccupation with de-fetishizing the photograph as a collectible to be preserved for its material qualities and perishable nature. Instead, the proposed digital archive would continue to provide material with which to work, its critical potential resting on gestures of juxtaposition, montage, and the creation of new constellations of image, text, sound, and storytelling located at a strategic distance from the dominant narratives rehearsed and replayed by the mass media. Zaatari’s installation profanes every apparatus it engages—cinema, television, radio—rendering their constitutive elements as tropes within the space of the installation.10For more on the profanation of the cinematic apparatus by visual artists, see Silvia Casini, “Engaging Hand to Hand with the Moving Image: Serra, Viola and Grandrieux’s Radical Gestures,” in Cinema and Agamben: Ethics, Biopolitics and the Moving Image, eds. Henrik Gustafsson and Asbjørn Grønstad (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 139–60. In this, the work unseats the unproductive and facile binary between “passive” and “active” spectatorship, the former associated with cinema and the latter with a multimedia installation that prompts movement.11The curator Mark Nash writes, “The ideological functioning of cinema spectatorship has, over the past fifty years, shifted to the wider, more fragmented and dispersed regime of the visual, encompassing advertising, television, mass circulation magazines and so on. Consequently, curatorial and artistic practices that are concerned with deconstructing and reconstructing spectatorship have had to find approaches that are not merely architectural. . . . I would argue that there can be no necessary connection between a particular formal approach to the conditions in which a work is experienced (e.g., creating a mobile spectator) and a presumed radicality.” Nash, “Art and Cinema: Some Critical Reflections,” 449. The composite media installation in a darkened room—itself an interstitial space between “black box” and “white cube”—with its challenge to both conventional cinema and the ideologically inflected gallery, is the setting in which Zaatari’s work is sited and experienced.

T. J. Demos’s arguments in The Migrant Image—The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis (2013) acknowledge recent artistic innovation in the face of a formidable “challenge [to] traditional documentary conventions, in order to investigate what political value accrues from those innovative strategies that negotiate the limits of representation yet nevertheless bring visibility to those who exist in globalization’s shadows.”12T. J. Demos, “Check-In: A Prelude,” in The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during the Global Crisis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), xix. Demos’s discussion of the exhibition Out of Beirut, held at Modern Art Oxford in 2006, is particularly useful in laying out the specific conditions within which the post–Civil War generation of Lebanese artists employs a poetics of the image, straddling their “fictional and conflictual aspects,”13Ibid., xxi. in engaging with a traumatic and unresolved history while resisting a “state-sponsored amnesia.”14T. J. Demos, “Out of Beirut—Mobile Histories and the Politics of Fiction,” in The Migrant Image, 181. In a political scenario marked by constant conflict, destruction, and loss, the task of re-creating history through the interpretation and study of fragmentary visual and textual information becomes a pressing concern for the artist. Mark Godfrey, in his 2007 essay “The Artist as Historian,” theorizes the origins of this trend and addresses—among other things—the work of Zaatari’s contemporary and occasional collaborator Walid Raad (Lebanese, born 1967), whose Atlas Group, a fictional collective that he conceived and cites as the author of many of his works, has engaged in the creation of a fictional archive of the Lebanese Civil War in an effort “to represent historical experience more adequately.”15Mark Godfrey, “The Artist as Historian,”October 120 (Spring 2007): 145. If Raad’s frequent inclusion in exhibitions and biennials has allowed his ideas around fiction and the political potential of the image’s questionable truth claims to gain traction within the spaces and discourses of contemporary art, Zaatari’s work with images and objects has emerged in a different vein. In many of his works, Zaatari relies on the study and presentation of shifting constellations of found elements, using them to uncover individual behaviors and personal experiences within the conditions produced by major historical events. In the work of both artists, fabrication plays a significant part—ranging from the invention of fictional accounts, individuals, and institutions (Raad) to the bringing together of disparate materials and narratives into multilayered assemblages (Zaatari).

The awareness of and interaction with multiple media apparatuses in the gallery space and the modes of spectatorship they produce is undoubtedly informed by the now canonical early experiments of artists like Paul Sharits (American, 1943–1993), Michael Snow (Canadian, born 1928), and Bruce Nauman (American, born 1941), with their revelation of the screen-reliant installation’s “phenomenological, psychic, institutional and ideological effects.”16Kate Mondloch, Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), xi. However, as curator Chrissie Iles pointed out in an October roundtable discussion following her important 2001 Whitney Museum exhibition Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–77, there was a reappearance of narrative in the work of experimental filmmakers and artists in the late 1970s and ’80s, marked by a move in the direction of “increasingly complex narratives and away from structural ideas, or process-based explorations of space.”17Malcolm Turvey et al., “Round Table: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art,” October 104 (April 2003): 72. Another participant in the roundtable, the early pioneer of projection-based works Anthony McCall (American, born England 1946), reiterated Peter Wollen’s thesis about the two avant-gardes and argued that the Godardian legacy that “stressed not material, but signification” has returned in the last decade “albeit in a new context—the art world.”18Ibid., 81. Also see Peter Wollen, “The Two Avant-Gardes,” in Readings and Writings: Semiotic Counter-Strategies (London: Verso, 1982).

Nearly two decades after this discussion and the accompanying exhibition took place, the regime of images and information is evermore subject to the insidious mechanisms of control exerted by both political actors and corporate behemoths. Within these conditions, Zaatari’s work uses multifarious apparatuses configured into an elaborate media architecture to present archival fragments and historical vignettes that underscore the politics of the image, and engage the dialectic between reception and distraction, awareness and immersion, art and documentary.19For more on documentary film installations in gallery spaces and their implications for spectatorship, see Elizabeth Cowie, “On Documentary Sounds and Images in the Gallery,” Screen 50, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 124–34.

- 1For more on Zaatari’s biography, see Mark Westmoreland, “You Cannot Partition Desire: Akram Zaatari’s Creative Motivations,” in Akram Zaatari: The Uneasy Subject, ed. Juan Vicente Aliaga (León: MUSAC; Mexico City: MUAC; Milan: Charta, 2011).

- 2A synopsis of All Is Well on the Border Front (1997) reads: “Three staged testimonies shed light on the experiences of Lebanese prisoners held in Israeli detention centers during the occupation of South Lebanon. Notions such as heroism and suffering are explored amid a dissection of the codes of representation and ideological indoctrination during times of conflict in this tribute to Jean-Luc Godard’s Ici et ailleurs.” Karl Bassil and Akram Zaatari, eds., Earth of Endless Secrets (Frankfurt am Main: Portikus; Beirut and Hamburg: Sfeir-Semler Gallery; Beirut: Beirut Art Center, 2009), 7.

- 3Akram Zaatari et al., The Pavilion of Lebanon at the “55. Esposizione Internationale d’Arte—La Biennale di Venezia,” exh. brochure, 2013.

- 4Akram Zaatari, Akram Zaatari: A Conversation with an Imagined Israeli Filmmaker Named Avi Mograbi (Aubervilliers, France: Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers; Paris and San Francisco: Kadist Art Foundation; Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 30.

- 5See “About the Arab Image Foundation,” Arab Image Foundation website, http://arabimagefoundation.org/getEntityFront?page=PageDetails&entityName=PageEntity&idEntity=1. The Foundation has, since its establishment, amassed a collection of more than six hundred thousand photographs drawn from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Egypt, Morocco, Iraq, Iran, Mexico, Argentina, and Senegal. Zaatari’s involvement in its activities has changed significantly following the first decade (he is no longer a member) in response to his thinking around the medium of photography, collecting, preservation, and the creation of large, centralized, physical archives in a time when technology allows for both the easy creation and proliferation of visual documents (still and moving) as well as their preservation through digital means. For more on this, see Akram Zaatari, “Interview by Eva Respini and Ana Janevski,” Projects 100, April 2013, https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/projects/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Interview-Akram-Zaatari1.pdf.

- 6Zaatari et al., The Pavilion of Lebanon at the “55. Esposizione Internationale d’Arte – La Biennale di Venezia.”

- 7Jean-Luc Godard. Histoire(s) du cinéma. 1988–98. DVD: 266 minutes. Chicago: Olive Films, 2011. See also Mark Nash, “Art and Cinema: Some Critical Reflections,” in Art and the Moving Image, ed. Tanya Leighton (London: Tate Publishing, 2008), 448–49.

- 8Jean-Luc Godard. Notre Musique. 2004. DVD: 80 minutes. New York: Wellspring Media, 2005.

- 9In a 2013 interview with MoMA curators Eva Respini and Ana Janevski, Zaatari stated, “It would be interesting to determine what exactly is essential to preserve. If emotions can be preserved with pictures, then maybe returning a picture to the album from which it was taken, to the bedroom where it was found, to the configuration it once belonged to, would constitute an act of preservation in its most radical form.” See Zaatari, “Akram Zaatari: Interview by Eva Respini and Ana Janevski.”

- 10For more on the profanation of the cinematic apparatus by visual artists, see Silvia Casini, “Engaging Hand to Hand with the Moving Image: Serra, Viola and Grandrieux’s Radical Gestures,” in Cinema and Agamben: Ethics, Biopolitics and the Moving Image, eds. Henrik Gustafsson and Asbjørn Grønstad (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 139–60.

- 11The curator Mark Nash writes, “The ideological functioning of cinema spectatorship has, over the past fifty years, shifted to the wider, more fragmented and dispersed regime of the visual, encompassing advertising, television, mass circulation magazines and so on. Consequently, curatorial and artistic practices that are concerned with deconstructing and reconstructing spectatorship have had to find approaches that are not merely architectural. . . . I would argue that there can be no necessary connection between a particular formal approach to the conditions in which a work is experienced (e.g., creating a mobile spectator) and a presumed radicality.” Nash, “Art and Cinema: Some Critical Reflections,” 449.

- 12T. J. Demos, “Check-In: A Prelude,” in The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during the Global Crisis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), xix.

- 13Ibid., xxi.

- 14T. J. Demos, “Out of Beirut—Mobile Histories and the Politics of Fiction,” in The Migrant Image, 181.

- 15Mark Godfrey, “The Artist as Historian,”October 120 (Spring 2007): 145.

- 16Kate Mondloch, Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), xi.

- 17Malcolm Turvey et al., “Round Table: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art,” October 104 (April 2003): 72.

- 18Ibid., 81. Also see Peter Wollen, “The Two Avant-Gardes,” in Readings and Writings: Semiotic Counter-Strategies (London: Verso, 1982).

- 19For more on documentary film installations in gallery spaces and their implications for spectatorship, see Elizabeth Cowie, “On Documentary Sounds and Images in the Gallery,” Screen 50, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 124–34.