In an effort to consider the variegated impacts of COVID-19 — a virus with a global reach — post has interviewed curators and directors from vital institutions around the world about how the pandemic has affected their conceptions and practices of programming, civic engagement, and care. In this interview, we speak with Gridthiya Gaweewong, Artistic Director of the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok, Thailand.

Wong Binghao: Hi, Jeab! I’d like to begin our interview by discussing the importance of engaging audiences, which I recall speaking with you about in Phnom Penh in late 2018. You are keenly aware that the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok, where you serve as artistic director, attracts many different demographics, from tourists to people who aren’t familiar with art at all. How have your strategies for audience engagement changed due to COVID-19?

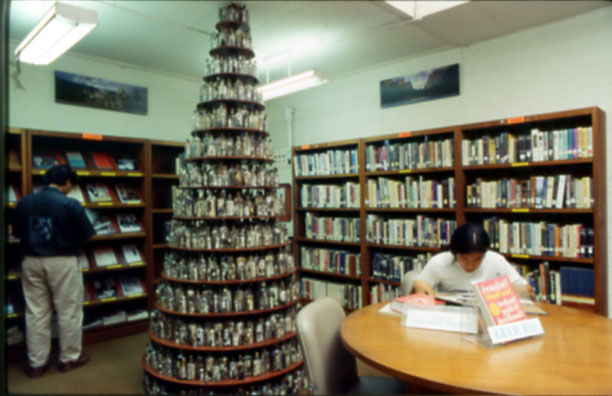

Gridthiya Gaweewong: These are difficult questions to answer because we lost touch with our audiences after closing our physical space in 2018, and then when we planned to open a new building, we were hit by COVID-19. But what we did and will continue to do is to create a variety of public programs that might appeal to different audiences, from schoolchildren to the general public to specific groups within the art community and academia. During that period, in the first quarter of 2020, we invited local artist Kornkrit Jianpinidnan (born 1975) to interact with our collection of William Warren’s books and use them as the point of departure to create his new series of photographs, printed materials, and moving images. The show was site specific to our library space, and it gave viewers different ways of experiencing the artwork. They could browse through the artist’s books, which Kornkrit installed on our bookshelves and tables. This project happened at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020, after which we were closed down because the city government announced the first lock-down. We extended the show and tried to conduct the public programs that we had already planned, which involved inviting guest speakers to talk online about queer teenagers and lifestyles in the Bangkok area during the Cold War. But the artists and guest speakers were not familiar with online platforms, and so they refused to participate. I found it quite interesting to see this, because though giving lectures online via Zoom seemed relatively new for the arts community here, we had done broadcasts via Facebook Live and YouTube before.

WBH: You have previously mentioned that your favorite part about curatorial work is meeting with artists in their studios to conduct research and gather information. What is a memorable or significant lesson that you have learned from artists?

GG: The most precious occasions, and those l always cherish, are the times that I spend with artists during studio visits or when I meet them in person. To visit an artist’s studio even just once or twice before the birth of a project is such a privilege. It’s like we are allowed to enter their context and their world. I really enjoy getting to know not only what kind of environment and ideas shape their mind and their thinking process, but also the way they deal with their reality, family, and community. This kind of information helps me to better understand their work, which is important when I have to conclude my research and make decisions. The most intense studio visit I had was during a trip to Beijing in the early 2000s. I went to China to do research for a show organized by the Japan Foundation called Under Construction. Beijing-based curator Pi Li, who was one of eight Asian curators invited by the Foundation to join this project, helped to arrange my time with artists. I met more than ten artists in one day! That was at the peak of the contemporary Chinese art scene. Our last studio visit was with Wang Gongxin (born 1960), whose studio was out of town. We returned to town to have dinner—Sichuan hot pot—around two o’clock in the morning. That was the first time I went to Beijing, even though I’d been to other Chinese cities like Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Guangzhou before. However, that kind of short trip, what people now call “parachuting,” is not so healthy as it’s quite intense and doesn’t allow for as much in-depth exploration. Maybe it’s okay to do it when you are still young and have energy. As I get older, I prefer to spend more time in one place, for instance through a residency program, to learn more about the context and art ecology of a particular city. For example, the residencies with IASPIS (International Artists Studio Program) in Stockholm, Asian Cultural Council, or the Japan Foundation Grants, which grant curators a one-to-six-month stay, are much better. Above all, what I get from a studio visit is a friendship that slowly develops with artists and their collaborators. This is the humanistic side of being part of the art community, and I have found it beautiful and rewarding.

WBH: In 2006, you made the observation that “in Thailand the difference between an organizer and curator is meaningless. If you have an idea you want to try, you make the laws yourself, and you do it yourself. That’s what it means to be a curator in Thailand.”1Quoted in Patrick D. Flores, Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2008), 161. I share your concerns about taking up the vaunted or universal label of “curator.” That is to say, curatorial work should be context specific. How do you think the situation in Thailand has changed, if at all, for curators and curating in the past two decades?

GG: Did I say that? I totally forgot about that quote, LOL. That kind of sentiment is history, since it was said around the mid-2000s, when Patrick (Flores) did a residency in Thailand. And I felt so bitter about working as a curator without infrastructure and moral support from the community. People in the arts and the society-at-large didn’t get the difference between the terms “curator” and “organizer”—they just called us “Poo JAD,” or organizers. There were not many museums or alternative spaces to help distinguish the difference between the commercial and nonprofit worlds, or the market and the museum/biennial art world.

But in the past decades, curating as a profession has become more visible because of the rise of such institutions as public and private museums and biennials, and the accessibility of information through social media. The younger generation is interested in this career, and finds being a curator a cool thing. So many young people further their studies abroad, and I find more and more people use the term “curator” in multiple contexts outside of the art world. However, students in Thailand still have to go abroad to study curatorial practices. Because of this, and the demands within the country and the region, the Jim Thompson Art Center has collaborated with Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts to launch a new online master’s degree program in curatorial practice next year. We will invite professional curators, theorists, and art historians in the region and beyond to teach, and plan to place interns with many institutions, as well as to have weekly seminars throughout each semester.

WBH: Your doctoral dissertation discusses what you describe as the “invisible curatorial practices” or “small narratives” in Thai and Southeast Asian art. For example, events like the Chiang Mai Social Installation (1992–98), an artist-initiated, self-organized festival. What other “small” or “invisible” practices or issues do you think deserve more critical attention?

GG: The idea of small narratives is an ongoing project. It has served as a parameter as well as a departure point since the beginning of my curatorial practice. My dissertation research focused on the exhibition histories and the art worlds of Southeast Asia, with a particular emphasis on artist collectives and artist-run projects like Chiang Mai Social Installation, Ruangrupa’s Militia and Video Art Festival, and TheatreWorks’ Flying Circus Project. Even though these case studies are quite different in nature, they are similar in that they were operated by artists. They feature bottom-up approaches and strongly critique state and institutions. They are like voices from below, “small narratives” that contest the grand narratives constructed and fabricated by the institutions within their specific contexts. In recent years, the other type of “small narratives” or “invisible issues” that I’m interested in have not only been about art history and how it was written, but also about socially engaged art in relationship to reality and history that we consider problematic, especially grand narratives like nationalist historiography. Recently, I find it fascinating that the younger generation, like secondary school and university students, who have been part of the student movements in recent years, have been interested in this topic and others—such as democracy and structural problems. There are also more publications on alternative and counter histories based on the PhD theses of local progressive scholars. This has contributed to an interesting intellectual movement in Thailand, though it has happened quite late compared to other countries in the region. The critical issues that are being discussed now include the decline of the democratic system, reforming the constitution and the lèse majesté laws, and disruptions by military intervention, such as several coups d’etat. These issues are the products and remnants of the colonial and Cold War histories. And this is probably why many local artists and scholars revisit this particular historical period.

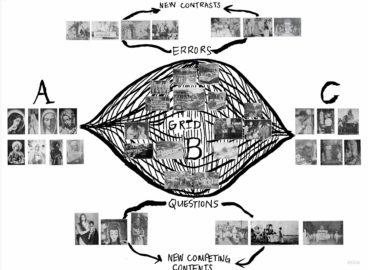

Currently, I’m working on a series of four exhibitions that are the result of a collaboration between the Singapore Art Museum, National Gallery of Indonesia, Hamburger Bahnhof—Museum für Gegenwart—Berlin, and MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum in Chiang Mai, and initiated by the Goethe-Institut. Titled Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories, this project focuses on the institutions’ collections. The idea for the series centers on alternative histories from Southeast Asia and beyond. My exhibition titled ERRATA looks at the MAIIAM collection as the errata of art collections in our local context, which resonates with regional and global histories of the colonial and Cold War periods. Future Tense, the inaugural exhibition in Jim Thompson Art Center’s new building, which is scheduled to open around the end of November 2021, will feature artworks by fourteen regional and international artists and will also deal with Cold War history from multiple perspectives. Many of the artworks that we have selected trace counter histories, collective memories, geopolitics, military strategies and their consequent effects in various contexts, from Asia to Eastern Europe and Latin America. I feel that artists and curators have to work together as archaeologists to excavate the untold histories and small narratives that can be relevant to our reality.

WBH: We share a love of good food. If you could describe your curatorial practice as a dish or ingredient, what would it be, and why?

GG: Great question, Binghao! Somtam (papaya salad), a spicy food for thought!!! It’s fresh, healthy, and complex. It consists of many flavors—sweet, salty, sour, savory, and spicy. Papaya, tomatoes, and chilies (some of the ingredients used in the dish) are the products of the colonial period, having arrived in Southeast Asia from Latin America through the Europeans. But our people localized these, and made somtam a “national dish,” which is very funny and debatable because it’s a signature dish from the Mekong region. The curatorial practices in our region are like these ingredients: they are also the products of colonization and modernization. But they have been contextualized and localized in our own context. I would consider somtam with lots of chilies as a metaphor for my curatorial practice. Whether through exhibitions or other kinds of art-related programs, I want people to experience the same effect as when they eat spicy somtam. After they see a show or join our programs, I want them to feel like they have had spicy food for thought ☺

- 1Quoted in Patrick D. Flores, Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2008), 161.