In an assiduous reading of Philippine modern artist Anita Magsaysay-Ho’s painting, In the Marketplace, art historian Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol discusses notions of gender, economic value, and spirituality.

There is always more at stake in a market than prices. So goes a fundamental lesson of anthropology. Beliefs, norms, obligations, and other non-utilitarian valuations are in play, together providing the scaffolding that gives meaning to material acts of exchange. In the Marketplace suggests something of the difficult task of picturing embeddedness. A hand clutching a bundle of cash is at the painting’s center, yet the significance of monetary transaction is subsumed into the fray. A raucous din suffuses the crowded composition, as figures jostle one another, pushing up against the tightly cropped frame. With their mouths open and limbs wildly gesticulating, the women appear to be engaging in a choreography that construes communication as commotion. Extended hands and pointed digits take on expressive lives of their own—the marketplace here being defined less by sovereign agents than by disjointed gestures of uncertain intentionality. A young girl to the left proffers an offering to an unseen divinity above. Another girl in the distant background has her eyes closed, as if this were all a numinous dream. God, or gods, inhabit the scene.

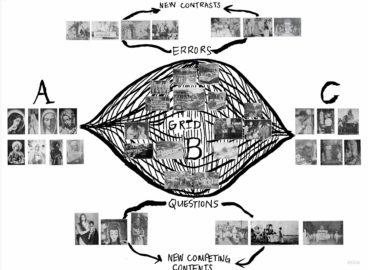

In the Marketplace was painted in 1955 by Anita Magsaysay-Ho (1914–2012), first cousin of then-president of the Philippines, Raymond Magsaysay, and in the words of a contemporary critic, “the most popular painter in the country.”1Emmanuel Torres, “Anita Magsaysay-Ho: Genre Painter,” Philippines International 2, no. 2 (December 1957): 24. The work’s subjects, native women with awkward, angular features, had been a “Magsaysay trademark” since her student days at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1947.2Alice M. L. Coseteng, “Trends and Prospects of Philippine Modern Painting,” Chronicle Yearbook (1961): 89–90. But this small egg tempera painting represents a particularly ambitious compositional attempt, featuring the largest group of figures the artist would ever assemble. Magsaysay-Ho must have anticipated In the Marketplace not only as a magnum opus of sorts, but also as a hot commodity. “The mere mention of a new Ho painting is as good as sold,” critic Emmanuel Torres marveled in 1957.3Torres, “Anita Magsaysay-Ho,” 25. Indeed, the work would later go on to shatter the auction record for a Filipino artist, selling for nearly four hundred thousand US dollars in 1999.4Christie’s, Southeast Asian Pictures, Auction 9909: Sunday, 3 October 1999 (Singapore: Christie’s, 1999). No wonder that Magsaysay-Ho’s detractors, both then and now, have interpreted her fascination with native women as symptomatic of an elite gaze trained upon an idealized world of the folk.5Alfredo R. Roces, Anita Magsaysay-Ho: In Praise of Women (Pasig City: Crucible Workshop, 2005), 43. In Roces’s words, “Filipiniana breathes in her paintings and beats in her heart.” Put in the most critical terms, the marketplace of her painting could be said to present a primitivist imagination of an economy unalienated from the spiritual.

Yet the strangeness of In the Marketplace—its refusal of the saccharine—belies plain nostalgic longing. Embedded as Magsaysay-Ho was in the booming art market, what would it mean to take her seriously, not only as a painter, but also as an observer of the economy? Could In the Marketplace be said to respond to its own condition as an exemplary artwork-commodity? The first step in answering these questions may be to revisit the idea of “moral economy,” toward which the painting gestures. The term broadly refers to the nexus of beliefs, obligations, practices, and emotions that underpin market exchange, and is often applied to describe subaltern resistance to the encroachment of modern price-making markets.6Jaime Palomera and Theodora Vetta. “Moral Economy: Rethinking a Radical Concept,” Anthropological Theory 16, no. 4 (December 2016): 413–32. But the rich have moral economies too, even if such economies encode unjust patterns of accumulation. Magsaysay-Ho had a front-row seat to new flows of transnational capital that, commandeered largely by Catholic, mestizo elites, fed the rapid development of postwar Manila.7See Anita Magsaysay-Ho: Isang Pag-Alaala / A Retrospective, exh. cat. (Manila: Metropolitan Museum of Manila, 1988). With this view toward its embeddedness in channels of elite desire, In the Marketplace is perhaps a response more to the world of its maker than that of its subjects.

The painting’s only male figure peers directly out, cutting through the commotion of the marketplace to meet the gaze of the viewer. Though located furthest back, he arguably feels the most psychologically present, if not connected to the physical world that we occupy. If this figure offers a measure of open communication between two parties, Magsaysay-Ho seems also to imply that such efficiency of means short-circuits the intrigue of the artwork. Moving forward from the man and to the right, gestures that invite conjecture and imagination play out. Two hands lightly brush in awkward tenderness, their disjoint scale denying the intimacy of a firm clasp. Talking at the same time, two women in the foreground vocalize with a vigor that makes palpable the airy interval that separates them. The broken sociality of these communicative acts suggests something of the difficulty of convening a world conjointly. But they also intimate, by touch and breath, the possibility of intersubjectivity. Discrete individuality and the directness of the gaze give way to forms of non-sovereign relationality. Next to the man, a woman has her eyes closed, in a withdrawal that reaches for another idealized mode of communication—that of otherworldly communion.

In the Marketplace may well serve as a meta-reflection on the communicative norms of the world that Magsaysay-Ho inhabited. Alongside booming real estate development in Manila, one of Asia’s most vibrant art scenes emerged, the consolidation of which legitimized the previously marginal profession of art criticism. As Marian Pastor Roces argues, prominent male critics of the decade habitually reached for a “language of mysticism,” straining for the “lost comforts” of religious authority.8Marian Pastor Roces, “The Outer Limits of Discourse,” in SHIFT: Critical Strategies, ed. Nicholas Tsoutas (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 1998); reprinted as “Art Text as Bricolage: Philippines,” in Gathering: Political Writing on Art and Culture, by Marian Pastor Roces (Manila: Museum of Contemporary Art and Design; Hong Kong: ArtAsiaPacific, 2019). Disgust, bafflement, attraction, surrender, marvel, enrichment, and release—these were the libidinal tropes that framed aesthetic judgment and the evaluative operations of the art market as heroic activity.9See, for instance, Ricaredo Demetillo, La Via: A Spiritual Journey (Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1959). But such fierce individualism was also diagnosed as (male) longing, rather than reality. “The situation,” Emmanuel Torres wrote in 1963, “calls for a gallery proprietor who has savoir faire, showmanship, a shrewd business sense, and money. But such a proprietor, we fear, is as mythical as the unicorn. This absence is lamented as much as the lack of a single qualified art critic who can actively cover the art exhibitions in the metropolitan papers to stir up awareness, pass critical judgment, inform, and help set up an art market.”10Emmanuel Torres, “The Odds Against the Painter,” Esso Silangan 9, no. 1 (1963). Against the backdrop of this desire for communicative bravado and sovereignty, Magsaysay-Ho’s intersubjective ploy gained an edge.

At stake was the figuration of the postwar economic actor—or actress. Elite, highly educated women such as Purita Kalaw-Ledesma (1914–2005) and Lyd Arguilla (1914–1969) took on executive roles at the helms of galleries and cultural organizations, becoming instrumental in imagining a yet-to-be-determined social order of the art world. “A gallery is both encourager and mentor,” explained Arguilla, founder and manager of the Philippine Art Gallery (PAG; est. 1951). “It teaches by visual demonstration, by elimination, by choice. When a gallery has set a standard for itself, it becomes a critic of art in the gentlest and most persuasive sense.”11Lyd Arguilla, “Definitions,” Scrapbook No. 8 (1957–58), 318–19, Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Archives, Manila. Arguilla’s personification of the gallery as exemplary subject—business proprietor and discerning critic rolled into one—suggests something of the edifying thrust behind the activities of the PAG, the postcolony’s first “Modern” art gallery. But as importantly, and perhaps indicative of operative patriarchal norms, Arguilla’s conflation of corporate entity, economic actor, and art critic also served to mask her voice, dissipating her agency into more abstract forms. Indeed, Arguilla and Kalaw-Ledesma, who founded the Art Association of the Philippines, would insist on framing their activities in terms of collective moral uplift, a far cry from Torres’s showman-proprietor.12Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, And Life Goes On: Memoirs of Purita Kalaw-Ledesma (Manila: Vera Reyes, 1994).

If Magsaysay-Ho animated In the Marketplace in an operatic register, the result is less a celebration of heroinic individualism than a claim to immanence. The marketplace as a site of pictorial representation offers a testing ground for the figuration of economic agents whose sense of communality takes precedence. The drama of group form harks back to the works of Hungarian-born American artist Zoltan Sepeshy (1898–1974), Magsaysay-Ho’s teacher at Cranbrook.13For more on Sepeshy’s work, see Laurence Eli Schmeckebier, Zoltan Sepeshy: Forty Years of His Work, exh. cat. (New York: Syracuse University, 1966); Elizabeth Gaidos, The Creative Spirit of Cranbrook: The Early Years (Bloomfield Hills: Cranbrook Academy of Art, 1972). Deeply affected by the mandate of civic unity promoted by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (1935–43), Sepeshy’s paintings center on scenes of synchronized action among figures at work, often touched by the providential hand of God. Magsaysay-Ho’s women carry distorted echoes of Sepeshy’s fishermen, rail operators, and framers—her teacher’s ideal of bodies unified through collective labor now reformulated as a concerted drama of gesticulations and calls in the marketplace. The importance of the individual recedes within a compositional order that finds value in the interrelation of its subjects. What spirituality could be read in her work suffuses the scene as the force that holds the possibility of a shared world together.

If the assertion of artistic integrity often implies a critique of market principles, Magsaysay-Ho championed precisely the opposite of distance. Her sense of integrity had everything to do with embracing the fray of the marketplace as a site of potentially transformative relationships. Such a belief animated the careers of many artists of Magsaysay-Ho’s generation. Even if In the Marketplace is exceptional, the connections that the work raises between artistic production, transnational economics, and faith should not be regarded as incidental to histories of Philippine modernism. An emphasis on art’s moral economy may reveal something of the deep-rooted beliefs and desires that animate the promises of collectivity, cutting across political divisions of right and left classically construed. How such morality becomes a smokescreen for other forms of exploitation is a story for another time.

- 1Emmanuel Torres, “Anita Magsaysay-Ho: Genre Painter,” Philippines International 2, no. 2 (December 1957): 24.

- 2Alice M. L. Coseteng, “Trends and Prospects of Philippine Modern Painting,” Chronicle Yearbook (1961): 89–90.

- 3Torres, “Anita Magsaysay-Ho,” 25.

- 4Christie’s, Southeast Asian Pictures, Auction 9909: Sunday, 3 October 1999 (Singapore: Christie’s, 1999).

- 5Alfredo R. Roces, Anita Magsaysay-Ho: In Praise of Women (Pasig City: Crucible Workshop, 2005), 43. In Roces’s words, “Filipiniana breathes in her paintings and beats in her heart.”

- 6Jaime Palomera and Theodora Vetta. “Moral Economy: Rethinking a Radical Concept,” Anthropological Theory 16, no. 4 (December 2016): 413–32.

- 7See Anita Magsaysay-Ho: Isang Pag-Alaala / A Retrospective, exh. cat. (Manila: Metropolitan Museum of Manila, 1988).

- 8Marian Pastor Roces, “The Outer Limits of Discourse,” in SHIFT: Critical Strategies, ed. Nicholas Tsoutas (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 1998); reprinted as “Art Text as Bricolage: Philippines,” in Gathering: Political Writing on Art and Culture, by Marian Pastor Roces (Manila: Museum of Contemporary Art and Design; Hong Kong: ArtAsiaPacific, 2019).

- 9See, for instance, Ricaredo Demetillo, La Via: A Spiritual Journey (Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1959).

- 10Emmanuel Torres, “The Odds Against the Painter,” Esso Silangan 9, no. 1 (1963).

- 11Lyd Arguilla, “Definitions,” Scrapbook No. 8 (1957–58), 318–19, Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Archives, Manila.

- 12Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, And Life Goes On: Memoirs of Purita Kalaw-Ledesma (Manila: Vera Reyes, 1994).

- 13For more on Sepeshy’s work, see Laurence Eli Schmeckebier, Zoltan Sepeshy: Forty Years of His Work, exh. cat. (New York: Syracuse University, 1966); Elizabeth Gaidos, The Creative Spirit of Cranbrook: The Early Years (Bloomfield Hills: Cranbrook Academy of Art, 1972).