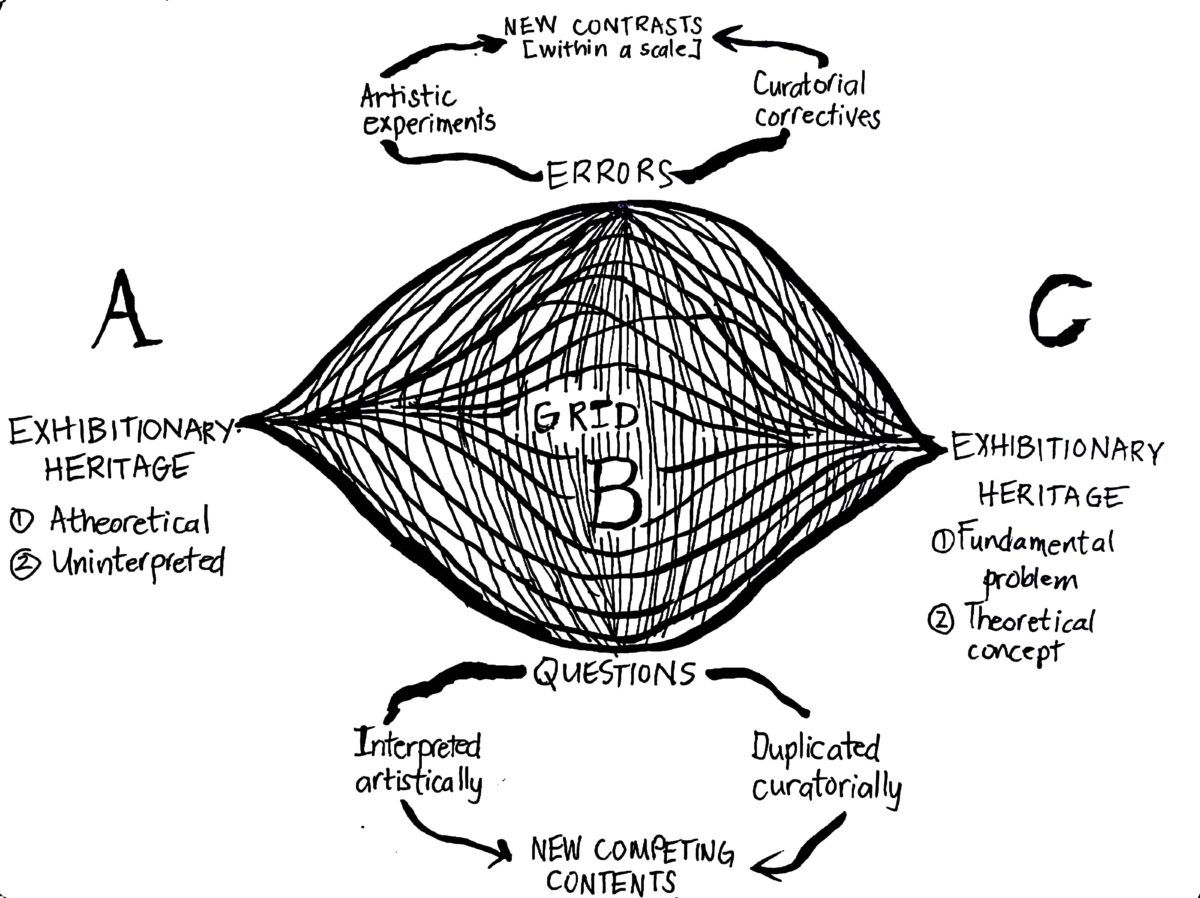

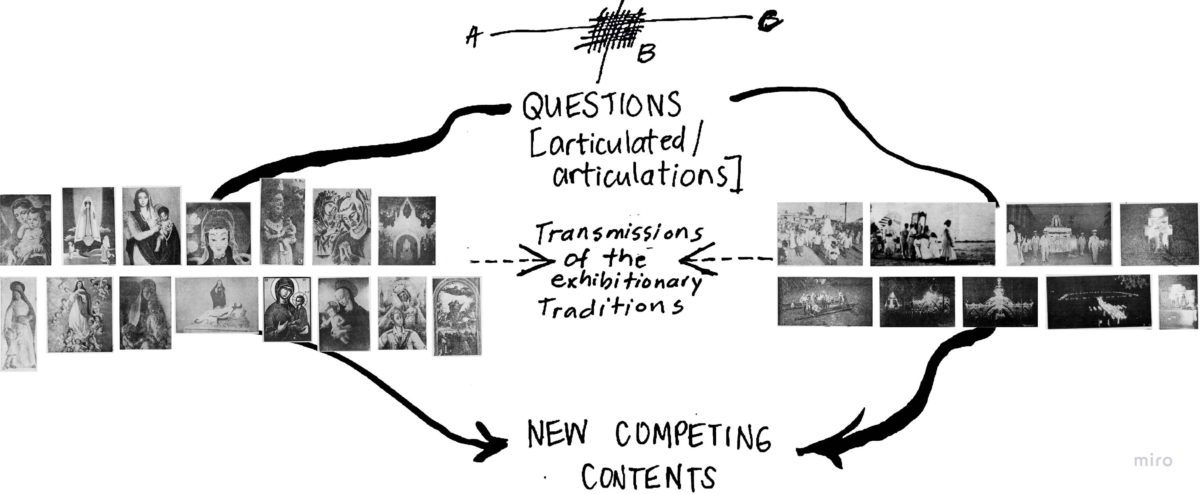

Treating as insightful case studies the records of miraculous, flower-flurried advents of Mary, Mediatrix of All Grace in the Mindanao Cross, a local newspaper founded by Catholic missionaries in Cotabato City, Mindanao, in 1948, researcher and curator Renan Laru-an initiates the notion of an exhibitionary heritage, articulating this proposition through a self-created grid.

In the race to fill the gaps in global art historiography, exhibition histories have recently emerged as justifiable sources in recuperating local, regional, and national art histories. They cross-reference exhibitions, the sites and events of artistic creation, with institutional memories and stable discourses. Any exhibitionary impulse of artists, curators, and other cultural professionals is extracted to formulate arguments for and case studies of the sufficiency of art ecologies—if not to serve as a referendum for a major art history. The tides of interest in re-presenting these exhibitions are initiated in the practice of curatorial monumentalizing, the legible registers of academia, and the legitimate data produced by archival exercises. These procedures generate new information that sheds light on formerly inaccessible details of artistic production, patterns of exchange, and public engagement. Exhibitions of works of art are believed to produce these materials. From this sampling, artists and curators validate the conception and use of the visual arts.

Within the current grasp of exhibition history, every exhibition is a tool kit, a restoration laboratory, and a gravesite of the historian’s archaeological adventure. Art exhibitions now school empiricist art histories in historical time; the north of a compass, the public showcase of art—be it solo or group, thematic or geographic, museum- or DIY-initiated, biennial-ized or commercialized—directs the assembly of missing documents by following the traces of creative itineraries in order to reconstruct the wholes of artwork, artist, curator, gallery, art school, magazine or journal, or museum within the schedules of modernity or contemporaneity. What happens, however, when such a constellation is left uninterpreted, when all other neighboring art-historical pathways are cut off from it?

Such art-historical absence is not entirely unthought of in creativity. Considered by some to be a capricious diagnosis of art’s realities or phenomena, this condition has since set forth demands for a thorough review of its manifestation in circuits and biographies of appearance. On the one hand, the demand comes from a normative understanding of an exhibition: it synthesizes the nature of the artistic in public exposure, when characteristics of art are technically approached via the instruments of exhibition-making. As we experience art on display, the artistic must be autonomously exhibitionary. On the other hand, when I close my eyes in the middle of a room filled with works of art, I should be able to distinguish this room from one that is empty or does not otherwise contain any traits of the artistic. This sensed quality, deemed an “apparition” by laypeople, is something that we art professionals have never granted to art. We expect the artistic to come to us in the form of objects distilled by exhibition-making. Yet the more sophisticated version of this arrival emits artistic ambience that envelops our senses. Thus, the exhibition of art crystallizes our experience, rendering the art knowable, convertible, and useful.

A room of artistic’s own is not only the hyperbolic tendency to make space and time. It is also an artistic demand that sites the exhibitionary outside the qualities of artistic being and becoming. Likewise, the practice of exhibition-making has since acted as a synthetic operation that reunites the work of art with the descriptive ideas of exhibition, a historical tool in its own right and ideally collaborative in terms of progressive art history. Exhibitions that organize tools in meaning-making and historical distance conditionally endow conciliatory power to the historicization of exhibitions: first, the task of interpreting the contents of the world in art, and second, the predisposition to discursify the experience of the exhibitionary in art. The room that can be leased to this essay is necessarily—and at the very least must be—miraculous.

Today it is hard to traffic the word “miracle” in contemporary writing since it once found clarity in terms of religious indoctrination. Especially in the rituals of criticism, the reach of such divination, if I could be allowed to convene that term here, in the threshold of critique liquidates its ambiguity in our psychic borders separating the artistic, the exhibitionary, and the curatorial. Miracles can disambiguate our beliefs. They doubt our kinship to the world. They precipitate history into the faithful that writes them all together. I am one of the believers, and so in this short essay, I will cite the documentation of a miracle as the heritage that we anticipate in living with our belief systems (including art).

The miracle is the Marian apparition that took place in the city of Lipa, Batangas, in 1948, and its documentation is the series of articles covering it, which are lifted from the pages of the Mindanao Cross, a local newspaper founded by Catholic Oblate missionaries in Cotabato City in 1948. The former contested to be supernatural while the latter is presumed to be non-art-historical: these two identities could very well be signatures of a miraculous event that sample the concept of exhibitionary heritage. The miraculous, cut from its contextual sources via its documentation, is in effect transplanted into an external, nonobjective medium. The scope of this essay, however, will neither widen to incite new propositions nor contract to deepen contextual analysis;1Readers familiar with Philippine history will note that these two postwar geographies on opposite ends of the archipelago have been abducted from their contexts (e.g., the region of Cotabato becoming the center of state-sponsored and illegal settlements of non-Muslim communities, the miracle instrumentalized in national and international anticommunist propaganda in the early Cold War, and so on). most likely foundational, it will remain within the problem of interpretation of what we have already received in the artistic, the curatorial, and the exhibitionary. The motion secondary to this one legislates exhibitionary heritage into an art-historical problem. The range of my tasks is thereby determined in the theoretical grid that howls: We all deserve miracles.

Reports of the Mary, Mediatrix of All Grace in the Mindanao Cross (1948–50)

| November 20, 1948 | Lipa Convent Receives Shower of Roses |

| February 5, 1949 | Our Lady of Lipa |

| February 19, 1949 | 500,000 People Attend Lipa Ceremonies |

| February 26, 1949 | A Visit to Lipa |

| April 16, 1949 | Want to Go to Lipa? Join the KC Pilgrimage |

| May 21, 1949 | Pilgrimage to Lipa on June 15 |

| May 28, 1949 | Pilgrimage Plan Hailed |

| May 28, 1949 | A Brief Account of the Incidents in the Carmelite Monastery–Lipa City |

| June 4, 1949 | Notice: No more requests for reservations to the pilgrimage to Lipa will be entertained after June 10, 1949. |

| July 23, 1949 | Rose Petals of Lipa Work Miracles Abroad |

| September 10, 1949 | Lipa Statue Sent to New York |

| October 8, 1949 | Our Lady of Lipa Statue Sent to Madrid |

| October 22, 1949 | Mass in Honor of Our Lady Mediatrix Next Saturday |

| January 28, 1950 | Archbishop Reyes Orders Probe of “Miracles” |

| February 4, 1950 | Stories About Lipa |

A.

In illuminating the overburdened tasks above, one can critically unsettle the objectives of an exhibition history through its interpretation. We have been acquainted with the exhibitionary that does not merely paraphrase/rephrase the work of art in works of art. The exhibition historian can certainly argue for the command of exhibitions in methodology ex post facto art history. Executed aright, such a historiography can invent an exhibition’s sources independent of artistic creation. This development can affirm the scientific legacy of an exhibition history whose principle has defined the entanglements of artistic manifestation with curatorial sensibilities.

The Marian apparition in Lipa in September and November 1948 was first reported by the Mindanao Cross toward the end of the same year. All of the publication’s fifteen headlines regarding the Virgin Mary, from late 1948 through early 1950, can be considered materials for an exhibition history. They are visual-cultural artifacts that site-specifically demonstrate public responsiveness to a national event. Proving local interest, these newspaper stories evidence that the peripheral can describe a subject of extraordinary caliber. The initial news about Mary, Mediatrix of All Grace, the form of address that she preferred, was written by an unnamed, local reporter who dramatized “a Manila newspaper woman’s” account as “rose petals suddenly fell in a shower about them. They drifted downward in graceful arcs and flooded the area with a sweet scent.”2“Lipa Convent Receives Shower of Roses,” Mindanao Cross (hereafter abbreviated as MC), November 20, 1948. This account signals that information can be mined from other sites or contexts and even across timelines. The coverage in the Mindanao Cross was already hinting at the universal accessibility of a miracle, i.e., its presence wherever one stands in the country, because after all, the petals fell from heaven. For the interpretive exhibition history, the miraculous can be filtered and parsed into elements that, when assembled, constitute background knowledge. The exhibition historian is a keeper of old documentation who is, from a practical standpoint, archiving new documents: the citation of the Virgin Mary in a newspaper in what is now Muslim Mindanao is expected to host and carry scientific traces of history, politics, and sociology. Unfortunately, when these documents are art historically determined, they cannot matter, because the miraculous remains on the edges of our material world. Uninterpreted, miracles and their documentation are merely transcribed into optional sites of knowing.

Let us unpack the earnestness of the exhibition historian. The cultural velocity in exhibition histories reflects priorities in interpretation based on its displacement within art historical techniques. Visual language previously rehearsed within art history, that is, at some points, the pure science of things, arrives in the sphere of art historical experience. We accept the force of this perspective because it constantly attracts the artistic, the curatorial, and the exhibitionary in our contemporary necessity to completely approach the faculties of exhibitions. By doing so, we hope to have a material-technological understanding of the exhibitionary. For example, the artist may hoard news clippings about Our Lady of Lipa that can fund any object or concept they make in their artistic milieu. The curator largely does the same thing in establishing the structures and scenes that welcome the most interesting object or artist. If exhibition history is patient or rich enough to drill the epistemological tunnels that will unearth the exhibitionary’s raw form when used by artists or curators, art history can finally unload its work into the open-pit quarries of exhibition history. Exhibition history must be approached like one of the industries of intellectual debate. Its formative force when tested in the field of arguments can intertwine categories that bind materials as much as complexify their meanings. At this point, the integrity of method is ensconced in the successful publication of meanings by an exhibition. Here, without the spatial and temporal participation of art history, the question of enactment becomes clear in the materiality of exhibitions, i.e., in the amount of matter that can be independently interpreted and audited in the dispersion of the exhibitionary. Donning interdisciplinarity, exhibition history undresses the theory in art right in front of exhibitions. It can never, however, stand over the heaven that showers rose petals. What then are the exhibitionary laws that describe the works of art when they are sited and cited within (the context of) exhibitions?

Having faith in exhibition history requires the restoration of insight: that “to see is to believe” is a heritage not only worthy of intellectual rigor, but also that risks the acuity of sight (the seer) in passionate misunderstandings, confusions, and rejections. No one demonstrates this more clearly than ecclesiastical authorities who announce that “miracles are possible, and that they have occurred; but in concrete, the prudent [believer] should be the last to accept an event as truly miraculous.”3See Eduardo P. Hontiveros, “Miracles and the Scientist,” Philippine Studies 8, no. 2 (1960): 259–70, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42720462. I cite this essay because it coincidentally conjures the exhibitionary heritage in its refusal of the miracle in Lipa. In the same article, the author concludes that miracles are only accepted after the force of facts. In itself, the heritage of beliefs contained in the traditions of “to see is to believe” is an instance of pure description of anything exhibitionary. It is a speechlessness that forms the smile upon contact with the miracle-like. For this reason alone, I raise the term “exhibitionary heritage” to the level of “exhibition history.” Many astute readers will find the former term essentially problematic. From our achievements in art history, or from our philosophical and psychological refinement of pompous seers, my proposition easily crumbles in deference to the conceptual excursions of visual culture in its deployment of the term “exhibitionary,” and in the cultural engineering of anthropology of “heritage.” Epistemology alone cannot fully endorse exhibitionary heritage when the concept itself is at once a reality, synthetic, and antithetical: exhibitionary heritage is a scaffolding that times, locates, and proliferates all that is exhibitionary—like a shower, or rainfall.

The shower of rose petals bearing the marks of the Virgin Mary in Lipa is the data of an exhibitionary signature. The event fits one description of the exhibitionary: the reports in the Mindanao Cross are exhibitions in the making. They are virtual. Transitory in written documentation and oral culture, they are continuously uploaded with the present participle. As the subject of inquiry, they seem homologous to exhibition history and the notion of the exhibitionary complex. Their diligent verbs cannot fully download these exhibitions: the former takes the past too seriously, and the latter assigns too much value in the progressive tense. The effective commentary of the exhibitionary complex chronically disentangles artistic creation and curatorial subjectivity against the prehistories and afterlives of an exhibitionary; this is the business of the politics of truth.4One example is Marian Pastor Roces’s essay “Crystal Palace Exhibitions” (2005), which addresses the structural and political adaptation of the Crystal Palace exposition within the biennial(-like) enterprise. First published fifteen years ago, this critical position continues to be franchised in editorial houses and writing workshops, effectively overutilizing the exhibitionary complex as a tool to describe the exhibitionary. It is an iatrogenic transmission of interpretation that locks the chronic conditions of exhibition-making out of the fluidity of artistic and curatorial ventures. It is crucial to note though that the matter in exhibitions is envisaged by both practices (exhibition history and exhibitionary complex), as if exhibitions develop in the self-containment of the heritage complex “to see” and “to believe.” Exhibition historians and critics indebted to the exhibitionary complex tend to eliminate the superstitious in the ludic tendencies of provenance and treatise. Two practical things happen here on the level of interpretation that at first glance appear to be one continuous procedure: The exhibitionary complex describes the problems of an exhibitionary heritage. The heritage of an exhibitionary can be known according to the operations of its complexities, where we find solutions to artistic problems in the description of exhibitionary complexes. But, like exhibition history, the practice of an exhibitionary complex recruits problems that have been conceptually sustained in the independent formation of artistic, curatorial, and exhibitionary problems. Both impulses are uniquely problematic and severely critical, but they are never unique problems per se. In this development, neither exhibition history nor the exhibitionary complex can take the exhibition of miracles to be the matter of exhibitions; they cannot turn falling petals into a miracle of content and form.

It is not surprising that many of us stumble upon the program of exhibition history (exhibitions about miracles) in the exhibitionary complex (the miraculous in exhibitions). The theory of the exhibitionary complex problematizes an exhibitionary heritage (miracles exhibiting themselves/self-exhibiting miracles) that the exhibition history theorizes to be its fundamental problem. Chronologically, eloquent judgment in these two popular schemata interprets exhibitionary heritage as an exhibitionary solution to problems that are represented by the works of art, which are supposed to correlate artistic solutions with fundamental artistic, curatorial, and exhibitionary problems. To see artistic solutions in the belief in an exhibitionary solution is a wasted opportunity that consumes the links between art, exhibits, and curation naturally and atheoretically. The starting program I propose here equates the relations of exhibition history with exhibitionary heritage, which emits a theoretical event that gives all exhibitionary “to see is to believe” the mass and energy to radiate on any given horizon. Exhibition historians and critics must detect a radiation in their own heritage of looking.

B.

Confounding the creation of art with the birth of an exhibition is one of the many individual problems of art history that has been churned in exhibition history. As history investigates the universe of artistic problems, it can no longer confirm the exhibition’s individual relationships to the system of art; we accelerate toward using the concepts and tools of exhibition history’s total interpretive function. The constant velocity of this interpretation can be altered when fundamentally the artistic is conceived in exhibitions and the exhibitionary in artworks. It is a practice that finds an interval of force.

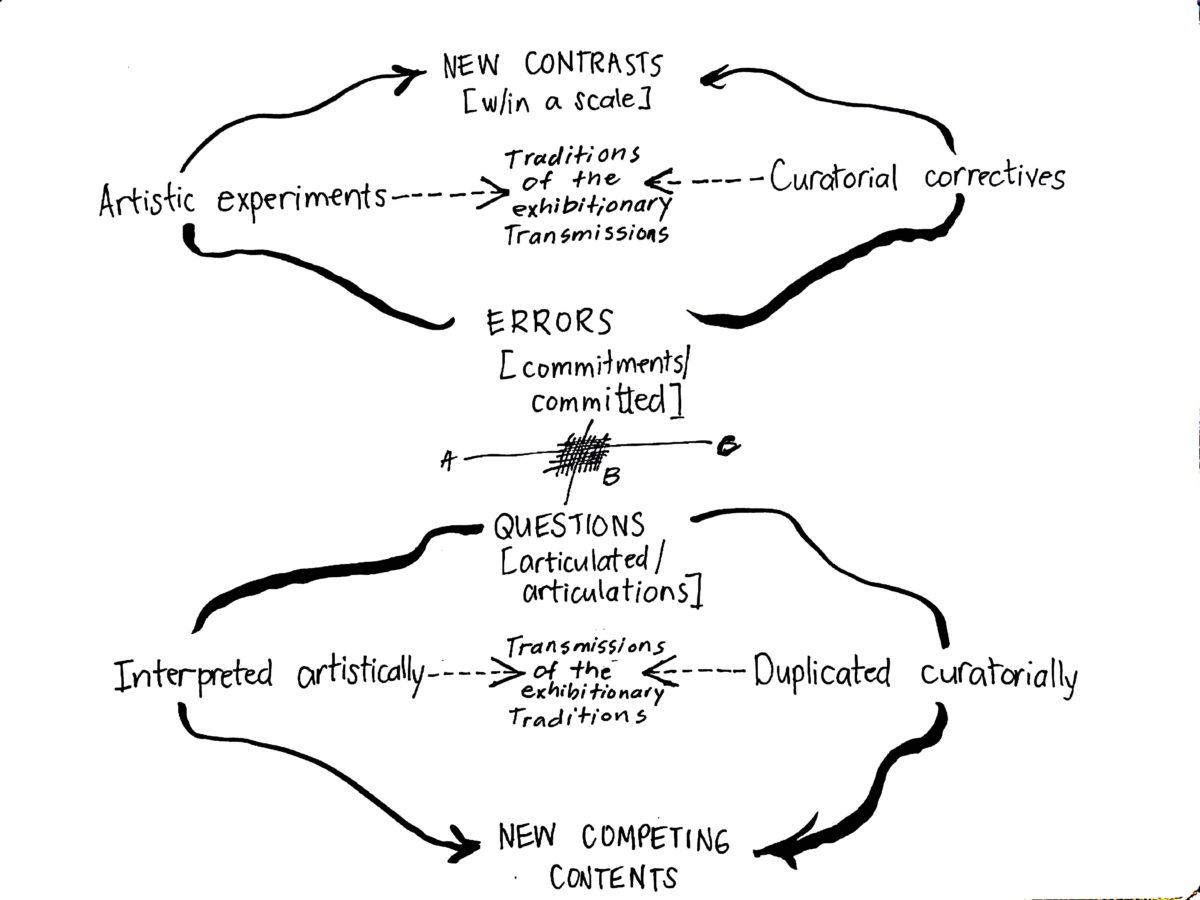

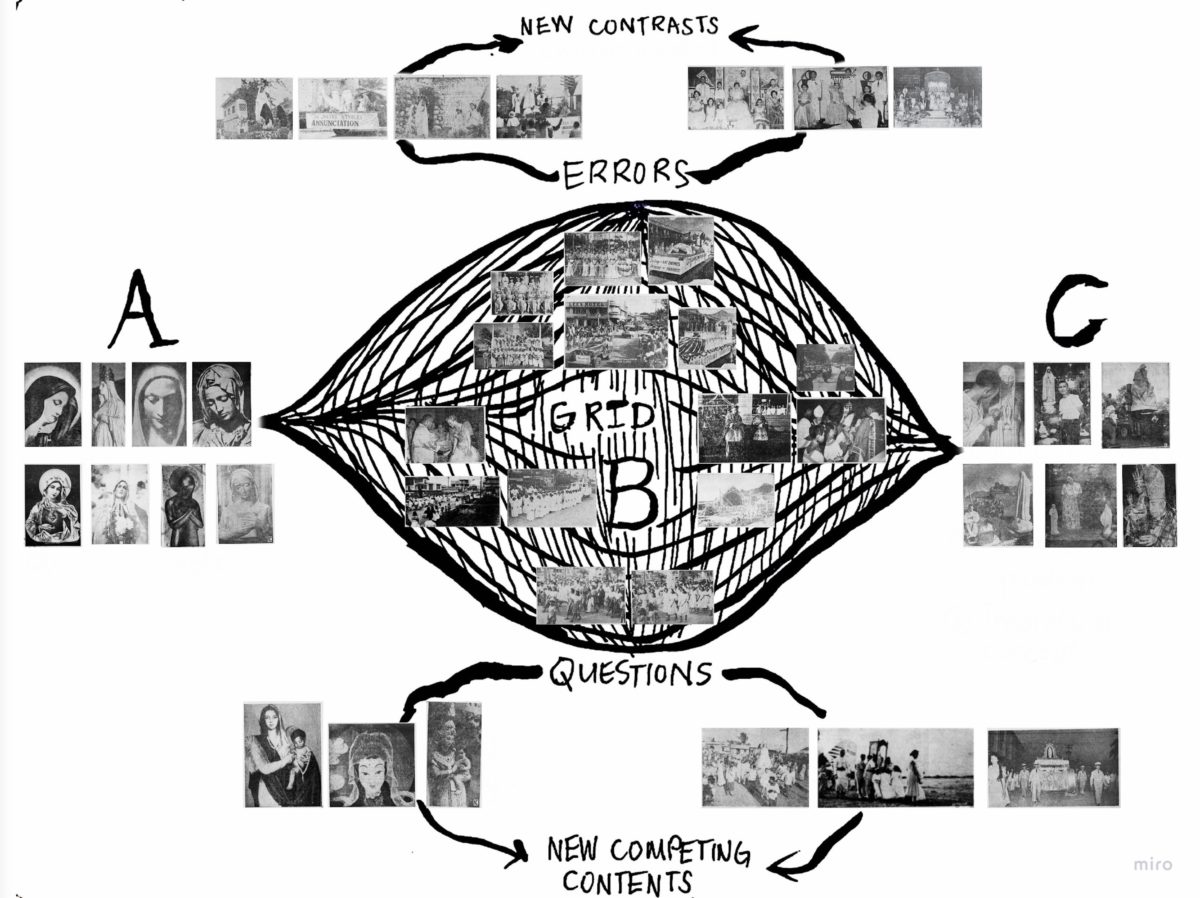

We enter in medias res. The structure below is a line that balloons into the shape of an exhibitionary heritage composed of crisscrossing tension, pulled outward by accelerating forces. The activity results in a theoretical grid. It is the volume of the artistic, the curatorial, and the exhibitionary, i.e., where their heritage traverses. This is the site of publication of the miracle in Lipa and its documentation in the Mindanao Cross. By publishing the fluctuating shape of a theory, the exhibitionary cannot be subtracted any longer in the activity of exhibition history; the material can be admitted to “a transcendental art-theoretical discipline or [in] a fully interpretative enterprise.”5Erwin Panofsky, Katharina Lorenz, and Jas’ Elsner. “On the Relationship of Art History and Art Theory: Towards the Possibility of a Fundamental System of Concepts for a Science of Art,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (Autumn 2008): 63, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/595628. Because the grid can postulate matter in terms of errors and questions and not necessarily in terms of exhibition or artwork, all the stories that emerge with the (non-)supernatural, non-art-historical are now responsive to the realities of historical making and the speed of hyper-historical data in “without art history.” The grid works as if there will be art history. This is the distinct feature of the exhibitionary heritage.

“Without art history” publishes the exhibitionary heritage of artistic (the miracle in ideas/objects), curatorial (categories of the miracle), and exhibitionary (the miraculous as datum of the world) practices. After this effort has been violently interpreted by prevailing art-historical concepts or has not been uniquely assigned in fundamental artistic problems, it collates lines that enhance the visibility of intersections in a scale of sensing and knowing. Publishing “without art history” searches for the second example of the exhibitionary, the all-important number that grounds exhibitionary heritage. This is the grid to be known in exhibition history (There is art history.) as a network of different weights of artistic, curatorial, and exhibitionary matter; to be articulated in or committed to exhibitionary heritage forces objectivity into inflation and deflation. In this grid, the miracle can be contained or can burst into the study of traditions and transmissions. Assumptions and interrogations interact continuously, forming little pockets in which additional materials find their places in these highways of meanings. Exhibition history is productive in widening the distance between the points of intersection; exhibitionary complex (There were art histories.) evaluates the truth of these converging points. Both will—during the expansion—at some points break into contents, falling as thousands of circumstances of exhibition-making. For example, the exhibitionary complex rightfully intervenes when it renders the subjectivity of an exhibitionary transparent to the public. In search of a “with” for art history, it re-misses the intrinsic “without-ness” in miracle, mirroring the condition of “without art history.” This is the force that entrenches the study of art in a history of ideas. For exhibitionary heritage to collaborate with art history, its tools must distribute the force of transmission and tradition deep into the source of problems. Exhibitionary heritage can do so because it treats the miracle as indivisible.

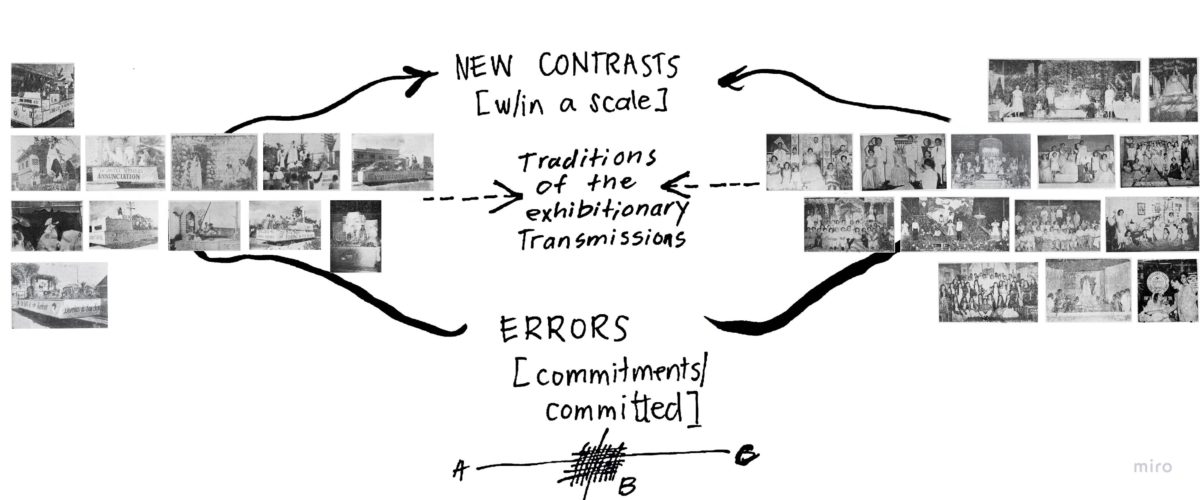

Miracle is content and form. This is the exhibitionary force that appoints our subjectivity along the scale and within the content of the world. The legacy of the exhibitionary complex and the influence of exhibition history are renewed in our tasks. Let us consider the representation of the Marian image in the repository of the Mindanao Cross. It symbolizes the narrative of miracles, and yet it lacks the miracle. Its abundance in the newspaper is meaningless, let alone without history, because the image is not graduated in descriptions. The grid bonds the objecthood of the image with our faith in the miraculous by linking the two with questions about experiments and correctives: What tests, errors, and accidents do they carry? How were these repaired, embellished, edited, and framed in order to be worthy of exhibition, printed on paper, and digitally archived? The material enters the system of new contrasts. The miraculous survives the erroneous, and therefore, it can live another timeline until the miraculous meets its inaugural artist and curator.

Any miracle is art’s direct competitor. This competition, even when it is declared to be fraudulent as in Lipa, grounds vernacular heritage in the literature that manifests the problematization of the exhibitionary into styles and types. The miraculous is the surrogate medium of the artistic, which shows itself unannounced because art is yet to be invented locally. Iconology approximates this immaculate content in cultural science; the triumph in image-text interpretation partially materializes “to see is to believe,” rerouting the miracle in objects and ideas in linguistic-conceptual heritage. The Marian image, the practices devoted to its iconographies, and the exhibitions promoting her aliveness in daily life penetrate the miracle empirically and physically. The panel below contains images that compose self-disclosing pageantry arising from Mary, Mediatrix of All Grace. For the sake of brevity, I point the viewer to the accretion of miracles in images from statues to fiesta, in cultural gatherings and processions that the Virgin Mary and her feminine likeness are suggested to pass through. What is central to these images is not the analogy to the Virgin Mary as the ultimate miracle, but how a miracle can turn the hopeful perplexity surrounding her into the relentless exhibitionary. The power of suggestion is curatorial, and so the materials can be rearranged—or other contents can be shaken off from them according to the demands of art history. This is the growing fragment of exhibitionary heritage that produces competing contents. These new pieces of information frustrate exhibition history as the emergent exhibitionary heritage puts forward more preliminary questions about the exhibitionary and the artistic, which, in this instance, might point us toward less stable documents in memory, nostalgia, and hope. This more forthcoming content is hospitable to experiments or interpretation. The exhibitionary is cultured in an aesthetic laboratory that relies on artistic reading and curatorial duplication: it diagrams the matter of the exhibitionary via, in this case, the pictorial6The next test for the exhibitionary heritage is within the realm of performativity, without linguistic kin or connection to the family of images that are suspended in hearing or speaking. It can also be experimented in the area studies of art. so that we can speculate the science in exhibitions. In short, the material in a miracle is experimental. It can be prospected and owned by chance instead of verification. The picture panel, in effect, apportions historical development so that we can reimburse our analytical propensity with a more fecund attention to regeneration, the method of the exhibitionary heritage that can be tested by art history.7Following this first essay on exhibitionary heritage, my next task is to clarify the decision to replace the word “absorption” with “accretion.” I think it is important to speculate the difference between the two in the contexts of “without art history” and the possibility of a matrix that can be alternatively used next to the diagram of transmission and tradition.

C.

This final section concludes the condensation of theory. Preceding statements cannot be elaborated further; research on the miraculous is inherently divorced from progress. An article published in the Mindanao Cross in February 1950, summarizes stories that still resonate among readers and that have been “certified to be true.”8“Stories About Lipa,” MC, February 4, 1950. One of them is the diagnostic analysis of rose petals sent to a famous American university laboratory. Two of the findings relate to the nature of the exhibitionary heritage: First, “the petals could in no way have ever been attached to a stem.” Second, “it was discovered that [the] particular variety of rose petals, which fell in Lipa, grow only in Russia.”9Ibid. These declarations have astounding impact on the migration of form and content. Supporting legitimacy, the article adds that these petals have been reported by pilgrims to transform: petals multiplying or turning into ashes. Miracles style the artifice of their likeness so much so that they surge in waves, defying the fact that they are uncommon.

The concept and object are replicated. Soon after the manifestation in Lipa, numerous other flower showers were recorded around the archipelago, compelling the Church to investigate the “genuineness” and “accuracy” of the events in order to suppress the “bad faith” that had conjured them.10“Archbishop Reyes Orders Probe of ‘Miracles,’” MC, January 28, 1950. More official missions were also initiated, such as the delivery of the Mediatrix replica to New York and Madrid during anniversary celebrations of the miracle. The weekly supplement of the Mindanao Cross, subtitled by four headings—ethics, philosophy, religion, and Catholic world news—mainly provided column inches for religious articles, except for in the case of the initial accounts of the Lipa miracle in the paper. One documentation of the Lipa miracle was, interestingly, positioned alongside another report on the coming of the statue of Our Lady of Fatima to Cotabato. The Mindanao Cross incidentally covered two types of Mediatrix apparition, the “false” and the “authentic,” the latter referring to the miracle in Fatima, Portugal in 1917, which was accepted to be a genuine supernatural event by the Vatican in 1946. The “authentic” Mediatrix gathered the communities in Cotabato to mark “an auspicious beginning for a lasting devotion.”11Editorial, “Our Lady of Fatima [. . .],” MC, July 23, 1949. Two issues of the fortnightly were reserved for this—one dedicating the main headline to it and the other running an entire page of photographs documenting the arrival of Fatima to Mindanao. The proximity of the original miracle to the local scene was quietly inverted in the lonely attention given to the substandard Lipa miracle12The Lipa miracle was also dubbed the first miracle in the “brown world” in the 20th century. See Deirdre de la Cruz, “The Mass Miracle Public Religion in the Postwar Philippines,” Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints 62, nos. 3/4 (September–December 2014): 425–44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24672319. in these issues that could have amplified the nearness of Lipa to Mindanao or the sameness of Lipa, Cotabato, and Fatima. Titled “Rose Petals of Lipa Work Miracles Abroad,” the report describes the miracle in its matter, the petal applied to the body of the sick and invalid, a sacred relic that is progressively distant yet proliferative.13Editorial, “Rose Petals of Lipa Work Miracles Abroad,” MC, July 23, 1949. On its surface, the Lipa petal revealed an image other than the Virgin Mary’s: that of Veronica’s Veil of the Sacred Face;14The Sacred Face is a devotional image representing the face of Jesus Christ, which was formed on the towel that St. Veronica used to wipe his face when he carried the cross. turned upside-down, the same subject redrawn in the petal’s natural vein. This representation proves that the Lipa petal was deceitful for not consistently carrying the Virgin Mary’s image; but could this be the Philippine Mediatrix’s claim to be officially exhibitionary? The configuration of faces on Lipa’s petals contrasts with that of Our Lady of Fatima, the benchmark of miracles, when she was perceived to be “brighter than the sun” by her visionaries.15For an overview of Our Lady of Fatima and the world-renowned description “brighter than the sun,” see Wikipedia, s.v. “Our Lady of Fátima, last modified June 13, 2021, 21:31 (UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_F%C3%A1tima.

The permanence of the exhibitionary is enshrined in description. I wish to summarize the problem of the exhibitionary heritage in order to discursify that even miracles can be interpreted art historically, that they are worthy of belief. Many would not believe this because “true” miracles are sustainably brilliant. The theory that purifies description enhances the agency of documentation. When the visionary Carmelite postulant Sister Teresita Castillo (1927–2016), on the second manifestation of Our Mother in her Lipa monastery cell, recalled the loss of sight (“Although I was blind . . .”16A two-part documentary titled The Woman Clothed with the Sun—Lipa Apparition (ca. 1992) chronicles the events in Lipa and registers Sister Teresita’s first-person accounts of the miracle. Produced and narrated by broadcaster June Keithley-Castro, the documentary bears the same title as other documentaries on the Virgin Mary. See https://ourladymarymediatrixofallgrace.com/the-woman-clothed-with-the-sun-2/.), she kissed the Mediatrix’s feet. Sister Teresita’s kiss is the theory of exhibitionary heritage. The entry in her diary after the event can be proposed here to be the formative force of the exhibitionary heritage in art history and elsewhere: “I could hardly believe it, but it is really very true. I felt I couldn’t do it, because I felt so unworthy. But I did it: My feeling was beyond description.”17This description is transcribed from the documentary. A fragment of her diary was published in a column in the past year. See Bernie Lopez, “Diary of Mediatrix Visionary Sr. Teresing,” Daily Tribune (Manila), September 23, 2020, https://tribune.net.ph/index.php/2020/09/23/diary-of-mediatrix-visionary-sr-teresing/. Interpretation beyond description. Art history, or any historiography for that matter, does not have a choice because Sister Teresita had actually done it. She literally ingested the exhibitionary when she obeyed the Mediatrix’s order: “Eat some grass, my child.”18Sister Teresita narrated this incident again in The Woman Clothed with the Sun—Lipa Apparition. Sister Teresita interpreted her theory in history. Functional unbelievability is the grid that anticipates all miracles to be the properties of an art-historical future.

This essay is part of an ongoing project titled Promising Arrivals, Violent Departures that (since 2018) is a curatorial study on the image-text production of/relationship in the community-oriented, culture-based publications Mindanao Cross (Cotabato) and Dansalan Quarterly (Marawi). The research has been supported by the Foundation for Arts Initiatives and National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

- 1Readers familiar with Philippine history will note that these two postwar geographies on opposite ends of the archipelago have been abducted from their contexts (e.g., the region of Cotabato becoming the center of state-sponsored and illegal settlements of non-Muslim communities, the miracle instrumentalized in national and international anticommunist propaganda in the early Cold War, and so on).

- 2“Lipa Convent Receives Shower of Roses,” Mindanao Cross (hereafter abbreviated as MC), November 20, 1948.

- 3See Eduardo P. Hontiveros, “Miracles and the Scientist,” Philippine Studies 8, no. 2 (1960): 259–70, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42720462. I cite this essay because it coincidentally conjures the exhibitionary heritage in its refusal of the miracle in Lipa. In the same article, the author concludes that miracles are only accepted after the force of facts.

- 4One example is Marian Pastor Roces’s essay “Crystal Palace Exhibitions” (2005), which addresses the structural and political adaptation of the Crystal Palace exposition within the biennial(-like) enterprise. First published fifteen years ago, this critical position continues to be franchised in editorial houses and writing workshops, effectively overutilizing the exhibitionary complex as a tool to describe the exhibitionary. It is an iatrogenic transmission of interpretation that locks the chronic conditions of exhibition-making out of the fluidity of artistic and curatorial ventures.

- 5Erwin Panofsky, Katharina Lorenz, and Jas’ Elsner. “On the Relationship of Art History and Art Theory: Towards the Possibility of a Fundamental System of Concepts for a Science of Art,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (Autumn 2008): 63, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/595628.

- 6The next test for the exhibitionary heritage is within the realm of performativity, without linguistic kin or connection to the family of images that are suspended in hearing or speaking. It can also be experimented in the area studies of art.

- 7Following this first essay on exhibitionary heritage, my next task is to clarify the decision to replace the word “absorption” with “accretion.” I think it is important to speculate the difference between the two in the contexts of “without art history” and the possibility of a matrix that can be alternatively used next to the diagram of transmission and tradition.

- 8“Stories About Lipa,” MC, February 4, 1950.

- 9Ibid.

- 10“Archbishop Reyes Orders Probe of ‘Miracles,’” MC, January 28, 1950.

- 11Editorial, “Our Lady of Fatima [. . .],” MC, July 23, 1949.

- 12The Lipa miracle was also dubbed the first miracle in the “brown world” in the 20th century. See Deirdre de la Cruz, “The Mass Miracle Public Religion in the Postwar Philippines,” Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints 62, nos. 3/4 (September–December 2014): 425–44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24672319.

- 13Editorial, “Rose Petals of Lipa Work Miracles Abroad,” MC, July 23, 1949.

- 14The Sacred Face is a devotional image representing the face of Jesus Christ, which was formed on the towel that St. Veronica used to wipe his face when he carried the cross.

- 15For an overview of Our Lady of Fatima and the world-renowned description “brighter than the sun,” see Wikipedia, s.v. “Our Lady of Fátima, last modified June 13, 2021, 21:31 (UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_F%C3%A1tima.

- 16A two-part documentary titled The Woman Clothed with the Sun—Lipa Apparition (ca. 1992) chronicles the events in Lipa and registers Sister Teresita’s first-person accounts of the miracle. Produced and narrated by broadcaster June Keithley-Castro, the documentary bears the same title as other documentaries on the Virgin Mary. See https://ourladymarymediatrixofallgrace.com/the-woman-clothed-with-the-sun-2/.

- 17This description is transcribed from the documentary. A fragment of her diary was published in a column in the past year. See Bernie Lopez, “Diary of Mediatrix Visionary Sr. Teresing,” Daily Tribune (Manila), September 23, 2020, https://tribune.net.ph/index.php/2020/09/23/diary-of-mediatrix-visionary-sr-teresing/.

- 18Sister Teresita narrated this incident again in The Woman Clothed with the Sun—Lipa Apparition.