In this short virtual interview, C-MAP Africa Fellow Nancy Dantas discusses Generator—a conceptual and infrastructural proposal, hinged on restitution—envisioned by curators Azu Nwagbogu (speaking from Nigeria) and Clémentine Deliss (responding from Germany) as part of their long-term program for the African Artists’ Foundation, Lagos. Established in 2007, the African Artists’ Foundation or AAF has been at the forefront of programming contemporary art and photography in Nigeria, and has helmed events such as LagosPhoto (since 2009) and the National Art Prize.

Nancy Dantas: Azu Nwagbogu, I would like to begin by congratulating you on maintaining and sustaining the Africa Artists’ Foundation over the past fifteen years. Can you tell us a bit about the foundation? What have the last fifteen years been like and what challenges are you faced with as an organization in COVID times?

Azu Nwagbogu: Thank you. It’s very kind of you to notice the effort and commitment it takes to run and sustain an organization like AAF. The time has flown by…

The COVID situation changed those parameters of AAF that we had taken for granted. It called a timeout on proceedings (to borrow the basketball parlance). In this interregnum we can observe more deeply and make adjustments. It has allowed for introspection and a re-evaluation of the modalities of our activities. More time for research, but equally for thinking of new infrastructure. Before COVID we were already rethinking AAF. LagosPhoto was cannibalizing AAF! The power, immediacy and distribution of photography and if you like the success of the festival and the desire for global-event-economy art-related situations with its celebratory position also brought on a weightiness and some complexities.

But about the ‘Covidian’ upheaval! If one thinks about it, on a certain intellectual and visceral level, there is a certain preparedness for the current dystopic pandemic condition we find ourselves in at the moment. The dominant trope with African contemporary and diaspora artists over the last decade, or perhaps even longer, has been an obsession with utopic and dystopic futures. Now that we have arrived at this moment, there is an almost tangible anticipation that change is imminent and that our activities at this moment could catalyze this change. Hence Generator.

ND: As I understand it, you are currently working with Clémentine Deliss on a long-term platform, Generator, whereby you will be thinking about and through collections and artefacts towards restitution. As part of the Lagos Photography Festival, you have commissioned the migratory artists’ cooperative Birds of Knowledge to design an online and interactive museum. This is one of the many manifestations that Generator will take. Has the collective started work on this platform? How is it being envisioned? When can we expect to see the fruits of this collaboration?

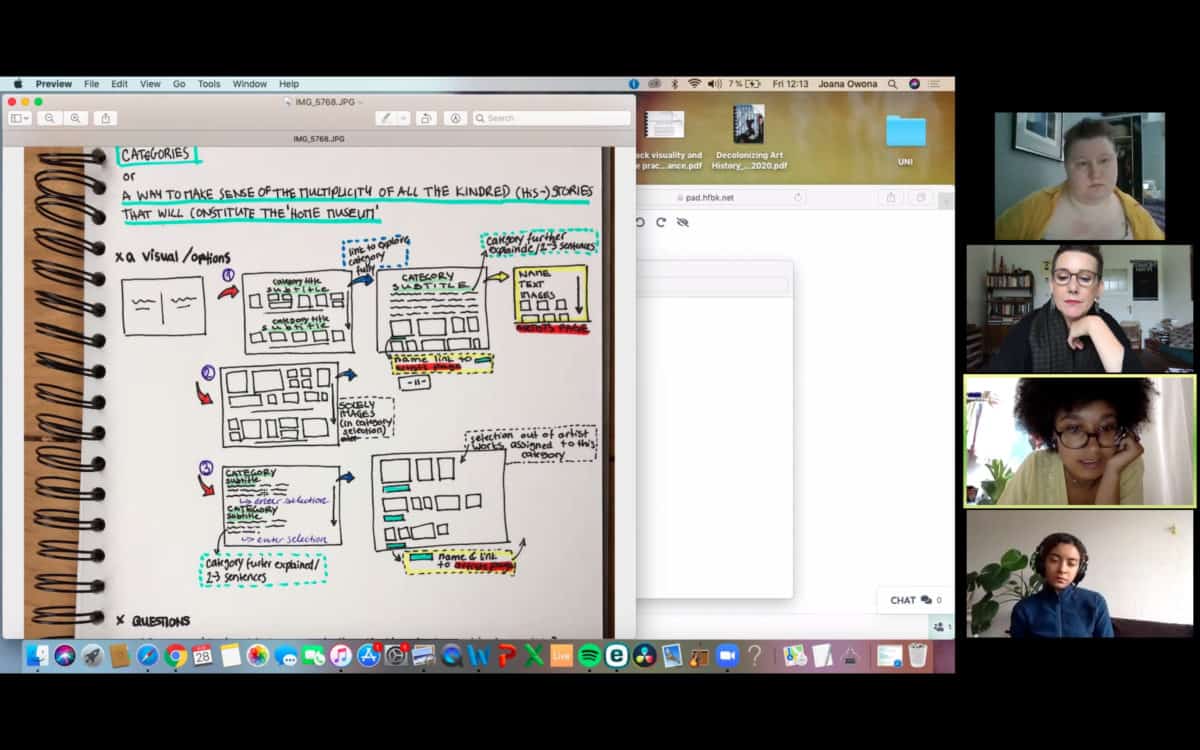

AN: Generator was devised by Clémentine Deliss and myself as a new infrastructure for an arts educational institution of the future. With Generator, we think about people, objects, experiences and their trajectories. Each dimension of Generator aims to provide a new frame for global creative thinking on how to best access, research, restitute and remediate Africa’s cultural heritage for the continent and beyond. That is how we also developed the concept of the Home Museum, by starting with the most intimate, domestic parameters in order to speak about a wider concern around cultural heritage and its repatriation. Clémentine’s students at the Hamburg Academy of Fine Arts set up a new research cooperative named Birds of Knowledge. The members are artists and social designers whose immediate origins hail from Nigeria, Tunisia, Cameroon, China, Turkey, Finland, Sweden, New Zealand, and Germany. They have devised different ways of engaging with the diversity of the Home Museum’s individual contributions. There are nearly 300 entries—from over 25 African countries and many others ranging from Saudi Arabia to China. We have commissioned Birds of Knowledge to build the actual online architecture for LagosPhoto20’s Home Museum.

We want visitors to the Home Museum to be intrigued and feel excited about their neighbours. We want people to recognize themselves and their own journeys in those of others. We want you to discover how different human experience can be, how meanings can be shared and yet remain individual at the same time. How an object of virtue can mean home, heritage, journey, and culture. How it can stem from a sense of family, be passed down through several hands, become a witness of time, a guiding figure, a carrier of memories, a teacher that helps you to re-imagine, or a symbol that acts as a painful reminder of past times. Ultimately the object of virtue has infinite meanings.”

We are working both on conceptual and infrastructural issues right now. We ask ourselves, what do we need to do to make the shift from an event-led economy to a new format of venue that is sustainable, responsible and experimental while practicing a decolonial and inclusive approach? We see restitution as an ecological question related to designs for survival, but also to play and forms of social living. For this reason, we broach the question from a trans-disciplinary perspective, crossing know-how and art forms, and generating trusted and stimulating dialogues. We want to help to empower young artists to engineer new models for social design by thinking through historical collections and traditional artefacts. This is something that Clémentine Deliss tested out at length during her directorship of the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt (see “The Metabolic Museum”, Hatje Cantz, 2020).

We aim to bring together an international and symbiotic faculty of virtual artists-in-residence, curators and other creatives. Students can study and connect through the online-campus of the “Generator Compound”. Digital visitors and researchers can use Generator to meet, talk, look, think, read, become inspired, and address their vocations. Online courses are based on providing instruction in practical and organizational skills as well as engaging with decolonial and post-ethnographic approaches to cultural theory, history, design, photography and art practice.

The start point for our current intervention with the Home Museum and Generator was actually based on the work we undertook between January and February 2020 when I invited Clémentine Deliss to research the situation on restitution in Nigeria. Together with AAF staff, Olayinka Sangotoye and Ugochukwu Emeberiodo, we went on a research trip visiting municipal museums in Nigeria.

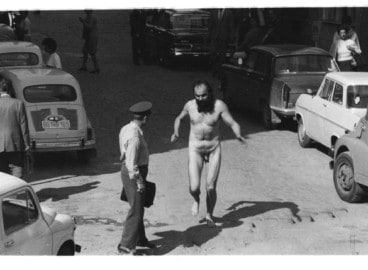

Clémentine Deliss: Let me begin please by expanding on Home Museum. At the start of 2020, as we were all forced into domestic isolation, the option to visit a museum and learn from exhibitions, artworks and collections from the past faded rapidly. Coincidentally, the return of artefacts, held since colonial times in the museums of the Global North, was discussed more than ever before. The Home Museum is born out of the connection between these two conditions. First, staying inside and reflecting on one’s immediate environment, family heirlooms and personal belongings. Second, initiating a visual conversation across continents on restitution and the role of the museum in the 21st century. Photography becomes the democratic vector for a process of rapid response restitution, or fast shutter retrieval, promoting greater awareness of cultural heritage both absent and present. One common factor to nearly all images is that they were taken in 2020, during the high point of COVID-19, by individuals living in home exile all over the world. The result is a remarkable collection of visual testimonials of the pandemic that are mediated indirectly through the Home Museum. Infused with humility, love, and generosity, each photograph says: “Come into my home, here is my history. This is my museum.” With the Home Museum, LagosPhoto20 triggers a grassroots discussion on how to restore the way one sees oneself culturally, on changing concepts of historical value, and on what should be cared for, preserved, and shared from a decolonial, African and global perspective.

Nearly three hundred individuals from homes around the world responded to an Open Call sent out through social media in May 2020. Drafted in Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, Swahili, Pidgin, English, French, Portuguese, Russian and Chinese, this was a letter addressed to a friend, an invitation to take part in co-creating a new virtual museum. “As we go about our busy lives,” it read, “we often forget the small things worth preserving – objects that are important to each person, family and home. Some treasures we use every day, some we keep, some we hold close, some we lose, and some are simply forgotten and not preserved at all. All these things bring back memories and tell stories about our culture and history in ways we don’t always recognize.” The brief was straightforward: to take part all you need to do is use your mobile phone to capture your own “Home Museum” and email a maximum of twelve photographs to LagosPhoto, accompanying these images with a short text describing their contents.

Several participants have staged their home as if it were a museum, setting up assemblages of objects, capturing the hang of their own art works, or gathering together personal archives. Together these installations reveal the humble realities of home life as a space of inhabited meanings that crosses over generations. The photographs evoke ways of living, but also highlight particular “objects of virtue,” artefacts that are singled out because they defy anachronism, maintain their aura, and personify memories cherished and renewed. These include different domestic appliances from cooking stoves to crockery, vases, clocks, watches, clothing, and money through to objects of vernacular devotion such as hair and vintage photographs. Others highlight early image-making technology such as cameras and phones, creating a double take on the artefact and the history of lens-based media. People too appear within the Home Museum, holding their exhibits like collectors, or standing in their revered space as if they were guards in an exhibition. Subjective interpretations of family, ancestry, identity, gender, migration, time, technology and healing are reflected in the way objects have been singled out and photographed by each individual, be they in Abuja, Bamako, Bogotá, or Beijing. Together these assemblages form a collective online museum, crossing space and time, where one can watch ideas flourish and develop alternative concepts of cultural value. If my home is my castle, then what I choose to photograph represents my museum.

ND: Besides the festival, you are collectively working on an open access library and digital bank. As I read it, you are proposing a living archive (in Stuart Hall’s acceptation) that is both an interruption and an intervention, a site that speaks to the future as it does the past and the choices ahead of us. Could you give us an indication of what researchers might find in this library?

AN: Libraries are the last stance against the noxious capitalism that threatens museology, culture, heritage. They provide the opportunity to have a fairer society. Everywhere in the world, hate and a lack of compassion are compounded by a lack of knowledge.

CD: I think we need to slow down the pace! The proposed Generator library will be built from the experience of the Home Museum. In a way, we already have both the producers, the faculty, and the students in one—this is the result of the democratic and grass roots approach we have taken to embracing a wide series of images that elucidate diverse notions of the museum. Thinking about collections and libraries, archives and museums, means re-considering classification and taxonomies. The library we plan will not be based on books in a room, or cabinets with files and index cards, either on paper or screen. It may be, that we locate the dynamic of knowledge transfer in the presence of specific people and their ‘libraries’, building an interdependent body of meanings outside of existing formats. So to give you more information on the library will require patience! As soon as we have learned from the Home Museum, we shall be able to define our concept of the library and digital bank in greater detail. This recursive approach is the only safety valve we have right now in order to avoid falling back onto colonially forged knowledge frameworks.

ND: In addition to the tremendous amount of work that you will be putting into the festival and library, you have also proposed an academy, “The Centre for Curatorial Know-How.” The Centre mirrors the Metabolic-Museum developed by Clémentine. Could you elaborate?

AN: We are all getting on and the success of what we build is only regenerative if we are able to share and nurture the next generation of custodians. We are careful to use the phrase “Know-how” because our approach is to be inclusive and decolonial in streaming knowledge systems that we believe work for Africa and its many diasporas.

CD: The Centre of Curatorial Know-How is the title I devised for a space of learning and experimentation that would enable non-academic as well as formalized research models to meet. Here students would appreciate the heterogeneity and inclusivity of what is understood to be “know-how” and more pertinently perhaps, what curating can involve today. I don’t believe that curating can be reduced to exhibition-making or exhibition histories. I see the value in an increasing connection between agronomic cultivation and the care and cross-fertilization afforded through working with artists and historical collections. Artists can remediate past violence, but only to a certain degree. Instead what is needed is a symbiotic relationship that adapts, like a poly-cultural shelter, so that there can be a flourishing of different worldviews and more specifically, of methodologies and practices of thought. The Centre should offer a means of empowerment to a variety of practitioners.

ND: How, and this is my last question, are you tackling the issue of digital inclusion, which is so pressing on the continent, and principally in places of learning?

CD: Digital inclusion is central to the development of Generator. By creating the Home Museum, we are working toward a new kind of digital architecture for museums! It’s easy to fall back onto the classic floor plan when you do an online museum. So this experiment will hopefully lead to a number of different ways for us to manipulate the digital and make it both inclusive and relevant to a wide audience. Meanwhile, I am very curious about the changes in museum architecture and new buildings for culture that may come about as a result of COVID-19. We know for sure that we need to rethink our use of museum space, prioritise other parts of these venues too, such as the storage spaces, perhaps turning them into new spaces for investigating the vast collections held by museums in Europe. Such access can lead to fantastic research and retrieval.

AN: This is a great place to end. Perhaps I could use this opportunity to mention the two guest curators working with Clémentine Deliss and I on the Home Museum: Oluwatoyin Sogbesan and Asya Yaghmurian. Oluwatoyin has been working on inclusive participation with museums for years now and has an approach to learning that incorporates WhatsApp and the common communication tools we use today. Asya Yaghmurian is an Armenian curator now based in Berlin who was instrumental in the last Ljubljana Biennial of Slavs and Tatars, and who worked with Clémentine on the project she curated for Hello World. Revising a Collection (Hamburger Bahnhof, 2018). Asya complements the position of Oluwatoyin, so that both reach out from different perspectives toward a new online reality. Interestingly, we all have this common history of working with existing museum collections as I too curated a chapter for Hello World along with Sven Beckstette.