In an effort to consider the variegated impacts of COVID-19—a virus with a global reach—post has interviewed curators and directors from vital institutions around the world about how the pandemic has affected their conceptions and practices of programming, civic engagement, and care. This interview marks the first of the series.

Ana Janevski/Sarah Lookofsky: A prescient place to begin would be with the final chapter of your book Comradeship, published last year. Titled “My Post-Catastrophic Glossary,” it is a kind of science fiction account of the aftermath of some unknown but cataclysmic event that has destroyed all material culture, including buildings and objects, with only memories left in its wake. You write:

These days we meet and talk in underground chambers, beneath the ruins of our former institutions; all we have left are our human resources. (…) No museums, no careers, no Documenta, no Venice. No competition over prestige, no funding, no government. Just a bloody fight for survival, with no hypocrisy or masquerades. I recognize now that this struggle did not start with the catastrophe. My years at the Moderna galerija were already a battle, one I hardly would have survived without a community held together not just by family ties or personal friendship but by a cause bigger than any of us as individuals. Through war to peace, through socialism to capitalism, from the Yugoslav dinar to the Slovene tolar and finally to the euro. The last moment, remember, when Slovenia joined the European Union, was somehow meant to signal the end of the great social transition! How ironic, then, that this transition was accompanied by the election of a right-wing government in Slovenia and, we feared, a new era of fascism. But that bad future didn’t last. The living memory of civil society from the 1980s was too strong. That spirit reawakened and answered the threat. A spirit of collectivism lives on, too, in L’Internationale, the international confederation of institutions launched in the very place where Nika and I sit now. Our museums are gone, and we don’t meet as often since we can no longer travel by plane. But our friendship has only grown stronger. Cynical reason having lost its purchase, there is now even greater idealism among us. The senses of solidarity and shared humanity once left in the dustbin of history are in the new light of aftermath being revived and redefined. I think we will survive this disaster. My friends are alive and I can hardly wait to see them roar again like young lions—to sit down with them again in some ruin and start planning a renewed world.

It is incredible to think that you published this last year, with a launch in New York, where we saw you. One could argue that version of what you described then has now come to pass: a global virus has ravaged countries around the world, with many institutions reeling as a result, some may not reopen. With this peculiar collapse of past and future, fiction and fact, can you talk about your thinking and planning as COVID-19 became a reality that demanded your institutional response?

Zdenka Badinovac: I believe two things I predicted in My Post-Catastrophic Glossary have come true with this pandemic: just as I had imagined, it took a disaster of planetary proportions to derail us, and we had to find ourselves without our museums, standing on their ruins as it were, before we could change our thinking. True, we were only left without access to our museums for two months, but the experience was quite sobering. Working from home taught us a great deal, lessons we may well revisit time and again. Clearly, museums will have to be thought about differently for quite some time; the epidemic can strike again at any moment, which is one of the reasons why planning costly exhibitions has become just too risky. Many of my colleagues working in museums want to show solidarity with others, it’s something we have discussed also within our confederation of museums L’Internationale—all of our member museums are ready to work differently now, to seriously consider redistributing funds to projects that could involve precarious artists and other external collaborators. Solidarity has become a key issue, not as an expression of our goodness, but as a condition of our collaboration in general, since otherwise prosperous institutions will only be able to collaborate with other prosperous institutions, which does not allow for the production of new knowledge. In the case of our institution, MG+MSUM, the situation is pretty dire: it was a low-budget institution even before this crisis, now things are bound to only get worse. I see a possible solution in diverse local and international agents coming together for projects that are sustainable, meaning that they involve care for others and a different economy of solidarity not based exclusively on market economy, but potentially involving also direct exchange of services and goods… Of course, people cannot live without money, so more than that has to be done; there is a lot of talk about public works, which might provide a source of income for artists, at least for a while. The state should provide funds for weathering this crisis both for artists and the sphere of culture in general. At MG+MSUM, we have decided to prioritize purchasing works from living artists, the dead can wait. A sustainable museum must lean on its constituents, forging various temporary alliances with them, alliances that are configured and reconfigured. We are probably about to face a time of major changes in institutions, which will assume a greater social role rather than follow the logic of cultural industries. Just like health care and education, culture and art also need to be predominantly publicly financed, as this corona crisis has proven.

AJ/SL: The opening essay of the book is your catalog essay for the exhibition “Body and the East,” 1998, which was the first international survey of the art performed in Eastern Europe from the 60s until the 90s. It included artists and researchers from fourteen Eastern European countries. You said that by putting body art at the center of the first EE survey about post avant-garde art coming from the East, you wanted to emphasize how body art incorporated important social experience and to discuss the representational character of “Eastern art.” Your interest in body art and performance is not engaged with the metaphysics of presence, but open-ended, social and mediated. COVID-19 has put the body at the center of attention: physical proximity is marked as potentially lethal; the representation of sick bodies is strangely rare despite the immensity of the global death toll; and new technologies of both tracking and digital interaction are precipitously advancing. How are you now thinking of the contemporary status of the body and whether it still involves any kind of geographic differentiation?

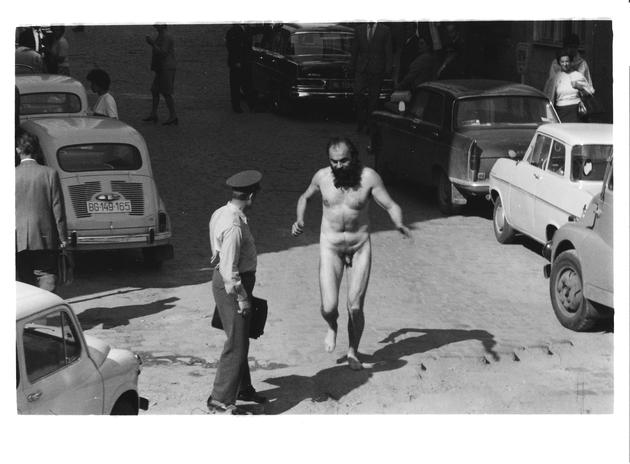

ZB: In my text for the Body and the East catalogue I wrote that Tomislav Gotovac streaking through the streets of Zagreb and Belgrade probably did not differ in action from other artists doing something similar in the streets of New York or London in the 1960s and 1970s. What was different, what is different is always the perception of the environment. In Yugoslavia during socialist times, such actions were automatically seen as political provocations. But then, they are also seen as provocation today. This week, two Slovene performers stripped in front of the building of the Ministry of Culture in Ljubljana in protest against the current cultural politics, and it was clear to everyone why they did it. A naked body may always look the same everywhere, but in reality it is not, nudity is always situated in the context of a specific socio-political moment and it is also interpreted as such. Another thing the coronavirus pandemic did was remind us of our mortality; our civilization had relegated death to the margins, but now the significance of rituals is being discussed again, saying goodbye to departed loved ones, mourning and grieving. I am currently working on an exhibition dealing with the notion of heroism, with the question of what we are actually prepared to die for. This is a very important question since it concerns freedom. With the numbers of authoritative state leaders increasing, freedom is in jeopardy, and the pandemic has contributed to this considerably. In body art, artists have often pushed themselves close to death in order to feel free. As we witness thousands of people dying of the coronavirus today, we naturally put empathy first, but that does not make the issue of freedom any less important.

AJ/SL: “Care: ‘relations [that] maintain and repair a world so that humans and non-humans can live in it as well as possible in a complex life-sustaining web.’ – Puig de La Bellacasa, 2017” is the opening line of a statement that the network of museums that you co-founded, L’Internationale, has issued during the coronavirus lockdown. Care and sustainability have been central to think about our present and future. You mentioned several times in your writing that an art institution should not merely respond to the context but create context or be a “revolutionary subject” of the time we inhabit. In her essay, Lockdown Theatre (2): Beyond the time of the right care: A letter to the performance artist, the writer and theorist Bojana Kunst quotes Puig de La Bellacasa and makes an interesting distinction between the “right care,” which follows norms, and “care with” that involves a knitting together of systems and processes of co-survival and support. Are there any recent examples of “caring with” that you can think of?

ZB: Art institutions can serve as the place where micro- and macro-politics can come together. This pandemic has brought “care” to the foreground as a key word that must be used with precision. Both Bellacasa and Kunst know what they are talking about and both have radical forms of care in mind. But I also think that this word gives emphasis to something that has long been inherent to art, and partly also to art institutions. Socially critical art always strives for a better world. It is simply a matter of not being indifferent, of caring about what goes on around us. And, having worked for an art institution for thirty years, I see it as essential that all these micro-efforts and experiences should be incorporated into the structures of education, culture, urban planning, etc. Sustainable solutions cannot remain confined to micropolitics, but can and must be protected by systems, and here is where museums can play an important role. They can at least enact something that the state should organize on a much larger scale. Because of the pandemic, museums lost many of their external collaborators and workers, such as museum attendants, educators, designers… Most of our museum attendants at the MG+MSUM are students and artists. When our museum buildings closed and the staff working from home, our external coworkers were suddenly out of work. In response, we launched the “Fill Two Needs with One Deed” action, employing our museum attendants to look after sick artists and pensioners by doing their shopping, talking to them on the phone or over video chat, etc. Not all who found themselves out of work were involved in this, but I nonetheless feel that this project was an important symbolic gesture of what an institution can do and that an institution should always take a stand and clearly express that it cares.

AJ/SL: There is a lot of discussion about whether there is a return to normal or what will be a “new normal.” In former Yugoslavia, there is an experience of the process of normalization after the war and then, following EU integration, a normalization through cultural integration, in which “culture” was more or less explicitly understood as a means of integration, of bringing Eastern Europe closer to standards of Western liberal-capitalistic order. The call for the online exhibition that the museum initiated in response to COVID-19, Viral Self Portrait, ends with “The future is either corona capitalism as the next stage of cognitive capitalism or else a corona rebellion against this standardization – and this is where art can play a major role.” We know you can’t predict the future but do you hold out hope that rebellion might prevail over normalization?

ZB: Today, we see people protesting all over the world. In Europe, they are rebelling against autocratic leaders and corruption, as is currently the case in Slovenia, Serbia, Hungary to name a few; in the United States, there is a veritable rebellion against racism; and soon there will be more and more fired workers in the streets around the globe. Until recently, progressive artists and theorists in the territory of former Yugoslavia looked back to the positive experience of socialism in their work, to a society of solidarity that no longer exists. While such revisiting of the past frequently bore a nostalgic note, this pandemic has forcibly pushed to the foreground the issue of the public healthcare system, as countries with predominantly privatized healthcare had great difficulties and high numbers of casualties. Where matters were not organized on the national level, people self-organized within their communities to help one another; we could see all manner of civil initiatives taking place. Care came alive in myriad micro-relations, and now it’s up to the large systems to learn from them. The experience of care “from below” is crucial in this moment; if macro-politics were to incorporate it, this would be a huge historical leap forward. There are still two possible outcomes before us: an even more ruthless form of capitalism or a society of solidarity.