Mama Casset is one of the first exhibited and most celebrated African photographers at work during the transition from colonialism to postcolonialism in Senegal between the 1920s and 1980s. His modernist photography was influenced by cinematic close-ups, glossy magazines, and his own aerial photography in the interwar period. Women were overwhelmingly his most recurrent sitters and patrons. Rather than passive recipients of the male gaze, his female subjects look and shine under the spotlight, becoming—in their reflexivity and reflectivity—active co-creators of a corpus that subverts the photographic medium’s reassuring chronotopes and thereby establishes new coordinates by which to see differently. This essay focuses on the female gaze, the role of light, and Casset’s vertiginous framing as three optical strategies that make palpable the women’s desire to look and to change reality.

By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: “Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.” —bell hooks1hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (New York: Routledge, 2015), 116.

There is power in looking. While some scholars and curators continue to salvage the oft erased stories of women behind the camera and in the darkroom, others have focused on female spectatorship and reclamation of the right to gaze.2See, for instance, Claire Raymond, Women Photographers and Feminist Aesthetics (London and New York: Routledge, 2017); Sandrine Colard and Laurence Butet-Roch, “Revisiting African Portraiture, Through the Female Gaze,” Aperture, posted December 18, 2019, https://aperture.org/editorial/laurence-butet-roch-african-portraiture-female-gaze/; Darren Newbury, Lorena Rizzo, and Kylie Thomas, eds., Women and Photography in Africa: Creative Practices and Feminist Challenges (Abingdon, Oxon, New York, NY: Routledge, 2021). It was bell hooks who detected among Black female viewers a distinct “longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze.”3hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 116. In approaching vision as “a site of resistance,” hooks invites readers “to search those margins, gaps and locations on and through the body where agency can be found” and scopic regimes are subverted.4Ibid. hooks builds her argument responding to both Michel Foucault’s reflections on “relations of power” and Laura Mulvey’s classic 1975 essay: Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Visual Culture: The Reader (London: The Open University, 2007), 381–89. This essay takes up hooks’s call by exploring photographic portraits in which female sitters are not mere objects of a male gaze, but rather present themselves as viewing subjects who dare to look.

I will consider select works from the rich corpus of Senegalese photographer Mama Casset (1908–1992), one of the most popular photographers in the transition period from colonialism to postcolonialism in West Africa (fig. 1). In his studio practice, women were his most assiduous patrons, commissioning dozens of portraits that would make him famous. Centering his subjects’ gazes under the spotlight and against blurred backdrops, Casset used all of the artifices—from the flash to framing—to subvert the photographic medium’s reassuring chronotopes and establish different ways of seeing. This essay focuses on the female gaze, the role of reflective light, and Casset’s vertiginous framing as three optical strategies that make palpable the women’s desire to look and to change reality.

Casset’s fame blossomed when he opened his own studio, African Photo, in 1942 in the heart of Medina, a popular and populous neighborhood in Dakar. His work was renowned across Senegal and beyond. Indeed, his Malian colleagues Seydou Keïta (1921–2001; fig. 2) and Malick Sidibé (1935–2016) both knew of his practice and mentioned his name in interviews.5Jennifer Bajorek, Unfixed: Photography and Decolonial Imagination in West Africa (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 61. Casset was one of the first African photographers to be featured in solo and group exhibitions in not only Africa but also the West in the early 1990s.6Bouna Medoune Seye, Mois de la photographie a Dakar (Dakar: Centre Culturel Français de Dakar, 1992); Bouna Medoune Seye and Jean Loup Pivin, eds., Mama Casset et les précurseurs de la photographie au Sénégal, 1950: Meïssa Gaye, Mix Gueye, Adama Sylla, Alioune Diouf, Doro Sy, Doudou Diop, Salla Casset, Collection Soleil (Paris: Editions Revue Noire, 1994). Scholars and curators alike have praised his portraits and described him as a pioneer of African photography.7Elisa Mereghetti, African Photo: Mama Casset (Fototracce, 2014), https://www.thedarkroomrumour.com/en/film/african-photo-mama-casset-a-documentary-film-by-elisa-mereghetti-senegal-photography. Building on this scholarship, I will complicate Mama Casset’s photographic modernism by considering the agency of his female clients.8On the photographer’s authorship and collaboration with his sitters, see Elizabeth Bigham, “Issues of Authorship in the Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keita,” African Arts 32, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 56–67, 94–96.

During his career, which spanned from the 1920s into the 1980s, Casset did not just take portraits. He began in the 1910s as an apprentice to established French photographers Oscar Lataque and Tennequin, developing negatives in the darkroom. Following this apprenticeship, Casset took aerial photographs across the region for the French air force; chronicled important political events as a photojournalist in Senegal (fig. 3); and photographed the interior of the country and pilgrimage of Muslims all the way to Mecca (fig. 4).9See Giulia Paoletti, “Un Nouveau Besoin: Photography and Portraiture in Senegal (1860–1960)” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2015). His practice thrived during the decolonization period and paralleled the rise of the urban middle class, which brought with it the advent of glossy magazines such as Bingo, and the genesis of African filmmaking.10Tsitsi Ella Jaji, “Bingo: Francophone African Women and the Rise of the Glossy Magazine,” in Popular Culture in Africa: The Episteme of the Everyday, eds. Stephanie Newell and Onookome Okome (New York and London: Routledge, 2014), 111–30. An agile entrepreneur and creative practitioner, he was fluent in the various languages of photography, gracefully moving between and across genres, and the demands and expectations that characterized them. Approached through such a framework, his portraits are not only faithful traces of his time, but also explorations of vision that invite us to let go of quotidian forms of looking and to entertain new perspectives.

Ways of Seeing

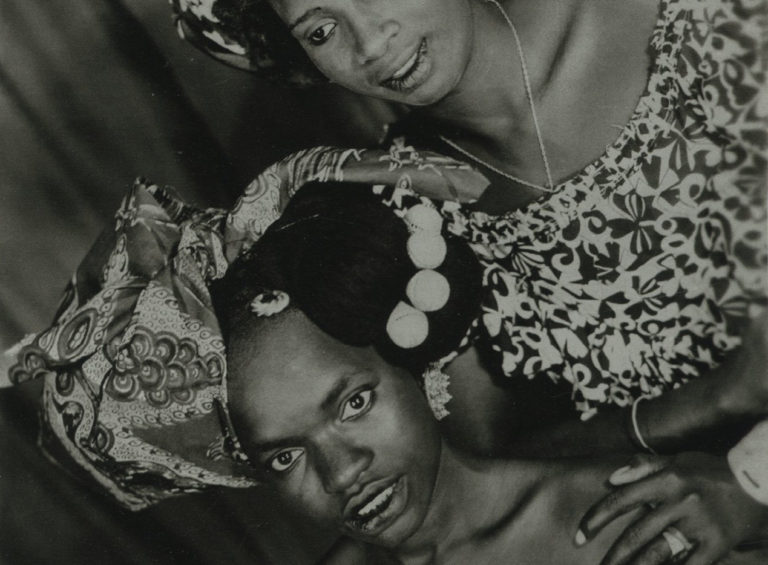

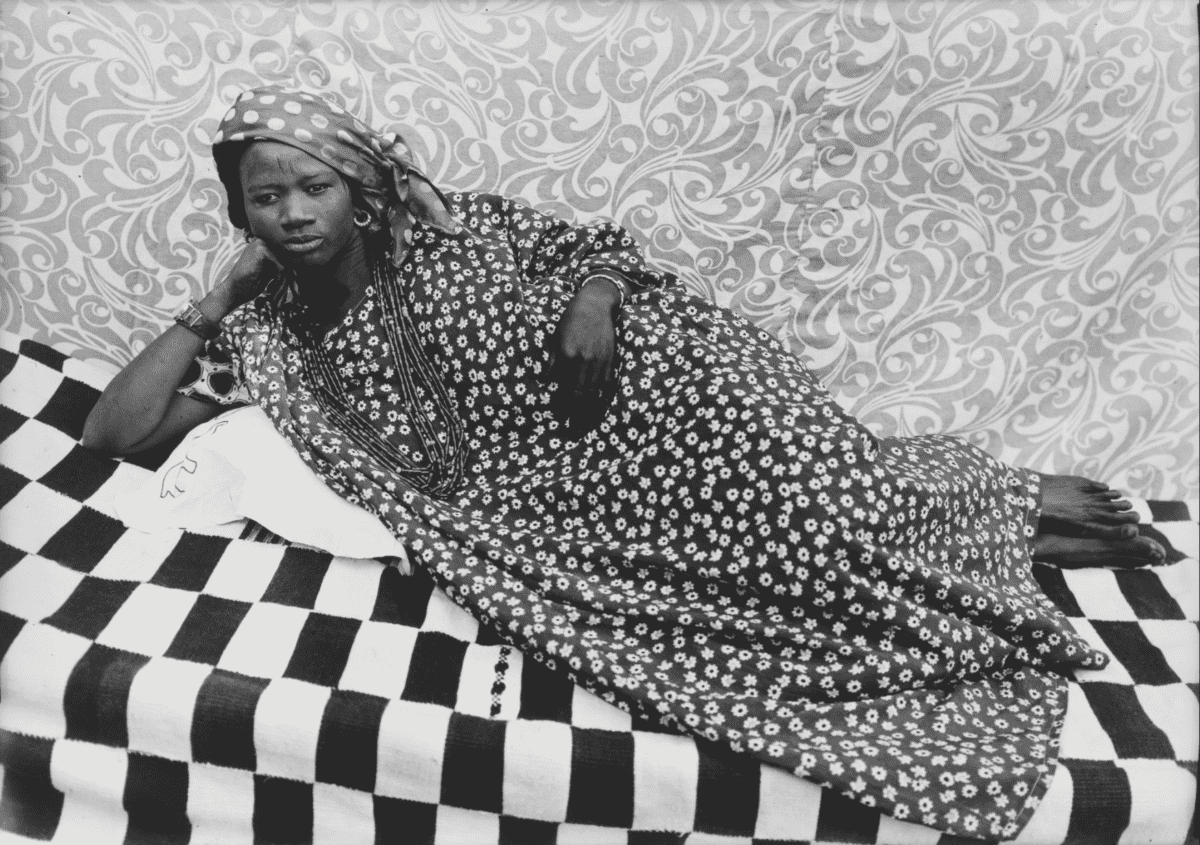

In one of his most memorable portraits, from the late 1950s, a woman poses in Casset’s studio (fig. 1). Encased in a tight frame, she is shown in three-quarter view, with her elbows resting on a table. Unlike in earlier portraits (figs. 2, 5), the sitter no longer stands under natural light or at a distance from the camera. Shooting in his studio and using the latest technologies, including a flash, Casset was able to zoom in on his subject’s perfectly oval face. In playing with the camera’s aperture and focal length, he blurred the background, creating a formal subordination whereby the sitter’s face is in sharper focus than any other part of the image. In this layered composition, her piercing eyes gain prominence (figs. 6, 7). Resolute in her averted gaze, she looks forward and yet away from the photographer. Her eyes, longing, her attire, shining—all point to her sensuality, not as an object of consumption, but as a desiring subject, the bearer of the gaze.

In various interviews I conducted in Senegal with female patrons of photography, the sitter’s gaze was among the features that regularly came up.11This essay and my larger book project are based on over 30 months of research in Senegal and hundreds of interviews with photographers, patrons, collectors and artists. Interviewees described her look as lampsal, a Wolof term for a woman’s way of opening and closing her eyes in a manner that is perceived as intriguing and seductive (fig. 1).12Soxna Noley Kumba Faye, personal communication, Touba, May 2014; Abdourahmane Niang, personal communication, Dakar, May 2014; Mariame Sy, personal communication, WhatsApp, February 2022. To American readers, this description may evoke the notion of “bedroom eyes” à la Marilyn Monroe. These two expressions do not perfectly match, however, as Monroe offers herself up to the camera, with her chin raised and her eyelids lowered, while the Senegalese sitter, her lips sealed, is looking up. Which is to say, these embodied ideas of seduction and femaleness do not necessarily align. The woman’s lampsalling, for example, is not specifically directed to a man; moreover, as she would be the primary consumer of such an image, it expresses, or better, figures forth, her ability to attract and conquer the reality she desires.

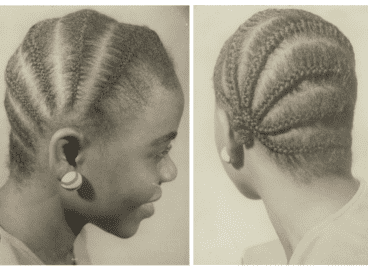

In another portrait by Mama Casset (fig. 8), the woman’s eyes are directed at the viewer. Though, slightly lowered and to the side, her gaze does not quite meet ours. This expression has been described as meditative and contemplating, and yet assertive, as she presents herself to the camera.13Ibid. In contrast to these two portraits, a third shows the sitter looking straight ahead (jàkk) with her eyes open (xool) albeit not bulging (xulli), wholly and unapologetically focused on her encounter with le reel, or the real (fig. 9).14On physiognomy and the role of eyes, see: Z. S. Strother, “Invention and Reinvention in the Traditional Arts,” African Arts 28, no. 2 (Spring 1995): 27–28, https://doi.org/10.2307/3337223. These are just three examples indicating the wealth of Wolof idioms used to describe eye expressions employed specifically by women, and here, foregrounded by Casset’s camerawork.

The sitters’ desire to see is further heightened by Casset’s artificial manipulation of light, which directs and distorts our viewing experience. In two examples, the blinding flash has occurred to the right of the photographer, and illuminates the sitter from above (figs. 1, 7). Under the spotlight, these sitters are not only visible but also literally shine, the bright and glittering surfaces of their jewelry and dress reflecting the radiance of the flash.15Krista Thompson has written extensively on techniques of light and surface effects, or what she terms “shine,” which create alternative epistemologies of representation. Thompson defines shine as “the visual production of light reflecting off polished surfaces or passing through translucent glass, to emphasize the materiality and haptic quality of objects.” Krista Thompson, “The Sound of Light: Reflections on Art History in the Visual Culture of Hip-Hop,” Art Bulletin 91, no. 4 (December 2009): 485, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27801642. In such details, in each subject’s ability to reflect light through metal earrings, a velvety dress, a hennaed lip—what bell hooks has described as “locations on and through the body”—we notice the image’s emphasis, its insistence, on shining reflection as light refracts and disrupts looking.

Mama Casset’s subversion of quotidian ways of seeing both photographs and women is visible not only through his exploration of gazes and shine, but also through his framing. In a number of portraits, Casset experiments with a particularly dramatic composition, in which the camera is turned at an almost 45-degree angle to the plane of reference. In one case (fig. 10), the diagonal that joins the print’s opposite corners functions as the main vertical axis for the composition. In another (fig. 11), the same framing technique and the light, now even stronger, create strong dark shadows in the folds of the backdrop, reinforcing the vigor of the portrait’s diagonal orientation. In a third portrait, the twisting of the image’s customary directionality is underpinned by the sitter’s aligned gaze, which is focused vertiginously downward (fig. 12). Critics have noted this diagonal aesthetic in Casset’s corpus, and among those of his colleagues across the region, foregrounding its dynamism and ability to convey the sitters’ agency.16Mama Casset and Jean Loup Pivin, eds., Mama Casset, Biblioteca Photobolsillo Biblioteca de Fotografos Africanos (Madrid: La Fabrica, 2011), n.p.; Bajorek, Unfixed, 57–65. But this framing also disrupts customary vision—that is, how these women were seen in real life and through a photograph—and offers new, albeit temporary, coordinates for regarding reality.

Casset’s radical dislocation of the camera’s orientation suggests a desire to destabilize the spatial grid, or what Christopher Pinney describes as photography’s “realist chronotope.”17Christopher Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image: Photography, Postcolonialism, and Vernacular Modernism,” in Photography’s Other Histories, ed. Christopher Pinney (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 216. The dramatic twisting of the camera’s angle dislocates habitual standpoints, and the effect is disorienting. The portrait’s placement is no longer consonant with a naturalistic view of the subject—as seen in colonial or historical photographs (fig. 6). Casset’s compositions were influenced by mass media and an imperative that was followed by many photographers between the 1930s and 1960s to emphasize “movement and diagonals.”18Martin Munkacsi, quoted in Maria Antonella Pelizzari, “Make-Believe: Fashion and Cinelandia in Rizzoli’s Lei (1933–38),” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 20, no. 1 (2015): 46. While perfectly still and sharp, the image encapsulates a forced movement—spinning—whose represented stasis can only be temporary. As such, Casset’s formal rotation and implied velocity echo the visual rhythm of cinematic editing and the compositional tempo of glossy magazines, all in sync with the speed of modern life, which did not have time for the eternal or everlasting. But it was also shaped by his extended practice as an aerial photographer whose experiments with perspective and abstract fields embody novel ways of seeing.

Unlike earlier Senegalese photographs, in which sitters are posed frontally under natural light, Mama Casset’s portraits play with directed gazes, blinding light, and unorthodox compositions, embracing the latest technologies and their possibilities. In most cases, the backdrops are monochromatic, and their purpose is not to lock the sitter into the chronotopic certainties or fixed temporal and spatial coordinates typical of Cartesian perspectivalism.19Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image,” 203. Rather, the backdrops function as a muted yet liberating device that resists the realist or narrative potential of photography. The “bareness” of the background draws attention to the sitter’s gaze and her ability to reflect light. This, and the formal strategies discussed above, suggest the photographer’s conscious exploration of vision and photography. It was Casset’s skill behind the camera, then, that transformed the pro-filmic into an announcement of photography as modernist art. Casset’s modernist strategies enable us to move beyond physical appearances and ordinary optical views of the world. In Mama Casset’s portraits, these women’s desire to look and to engender new ways of seeing becomes possible.

I would like to thank Christa N. Robbins, Mariame Iyane Sy, Mamadou Dia, Z. S. Strother, and Sandrine Colard for their invaluable feedback and suggestions as I developed this essay.

In reproducing the images contained in this text, the Museum obtained the permission of the rights holders, whenever possible. If the Museum could not locate the rights holders, notwithstanding good-faith efforts, it requests that any contact information concerning such rights holders be forwarded so that they may be contacted for future editions.

- 1hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (New York: Routledge, 2015), 116.

- 2See, for instance, Claire Raymond, Women Photographers and Feminist Aesthetics (London and New York: Routledge, 2017); Sandrine Colard and Laurence Butet-Roch, “Revisiting African Portraiture, Through the Female Gaze,” Aperture, posted December 18, 2019, https://aperture.org/editorial/laurence-butet-roch-african-portraiture-female-gaze/; Darren Newbury, Lorena Rizzo, and Kylie Thomas, eds., Women and Photography in Africa: Creative Practices and Feminist Challenges (Abingdon, Oxon, New York, NY: Routledge, 2021).

- 3hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 116.

- 4Ibid. hooks builds her argument responding to both Michel Foucault’s reflections on “relations of power” and Laura Mulvey’s classic 1975 essay: Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Visual Culture: The Reader (London: The Open University, 2007), 381–89.

- 5Jennifer Bajorek, Unfixed: Photography and Decolonial Imagination in West Africa (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 61.

- 6Bouna Medoune Seye, Mois de la photographie a Dakar (Dakar: Centre Culturel Français de Dakar, 1992); Bouna Medoune Seye and Jean Loup Pivin, eds., Mama Casset et les précurseurs de la photographie au Sénégal, 1950: Meïssa Gaye, Mix Gueye, Adama Sylla, Alioune Diouf, Doro Sy, Doudou Diop, Salla Casset, Collection Soleil (Paris: Editions Revue Noire, 1994).

- 7Elisa Mereghetti, African Photo: Mama Casset (Fototracce, 2014), https://www.thedarkroomrumour.com/en/film/african-photo-mama-casset-a-documentary-film-by-elisa-mereghetti-senegal-photography.

- 8On the photographer’s authorship and collaboration with his sitters, see Elizabeth Bigham, “Issues of Authorship in the Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keita,” African Arts 32, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 56–67, 94–96.

- 9See Giulia Paoletti, “Un Nouveau Besoin: Photography and Portraiture in Senegal (1860–1960)” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2015).

- 10Tsitsi Ella Jaji, “Bingo: Francophone African Women and the Rise of the Glossy Magazine,” in Popular Culture in Africa: The Episteme of the Everyday, eds. Stephanie Newell and Onookome Okome (New York and London: Routledge, 2014), 111–30.

- 11This essay and my larger book project are based on over 30 months of research in Senegal and hundreds of interviews with photographers, patrons, collectors and artists.

- 12Soxna Noley Kumba Faye, personal communication, Touba, May 2014; Abdourahmane Niang, personal communication, Dakar, May 2014; Mariame Sy, personal communication, WhatsApp, February 2022.

- 13Ibid.

- 14On physiognomy and the role of eyes, see: Z. S. Strother, “Invention and Reinvention in the Traditional Arts,” African Arts 28, no. 2 (Spring 1995): 27–28, https://doi.org/10.2307/3337223.

- 15Krista Thompson has written extensively on techniques of light and surface effects, or what she terms “shine,” which create alternative epistemologies of representation. Thompson defines shine as “the visual production of light reflecting off polished surfaces or passing through translucent glass, to emphasize the materiality and haptic quality of objects.” Krista Thompson, “The Sound of Light: Reflections on Art History in the Visual Culture of Hip-Hop,” Art Bulletin 91, no. 4 (December 2009): 485, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27801642.

- 16Mama Casset and Jean Loup Pivin, eds., Mama Casset, Biblioteca Photobolsillo Biblioteca de Fotografos Africanos (Madrid: La Fabrica, 2011), n.p.; Bajorek, Unfixed, 57–65.

- 17Christopher Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image: Photography, Postcolonialism, and Vernacular Modernism,” in Photography’s Other Histories, ed. Christopher Pinney (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 216.

- 18Martin Munkacsi, quoted in Maria Antonella Pelizzari, “Make-Believe: Fashion and Cinelandia in Rizzoli’s Lei (1933–38),” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 20, no. 1 (2015): 46.

- 19Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image,” 203.