Like other printed books of the time, Syed Sheikh Syed Ahmad al-Hadi’s two-volume novel Hikayat Faridah Hanom (The Story of Faridah Hanom), published in Penang in 1925 and 1926, notably incorporated photographic images that were likely repurposed from European magazines. Analyzing the text and images in the novel, art historian Simon Soon makes a case for a Southeast Asian modernism that is dynamic and unfettered by cultural binaries.

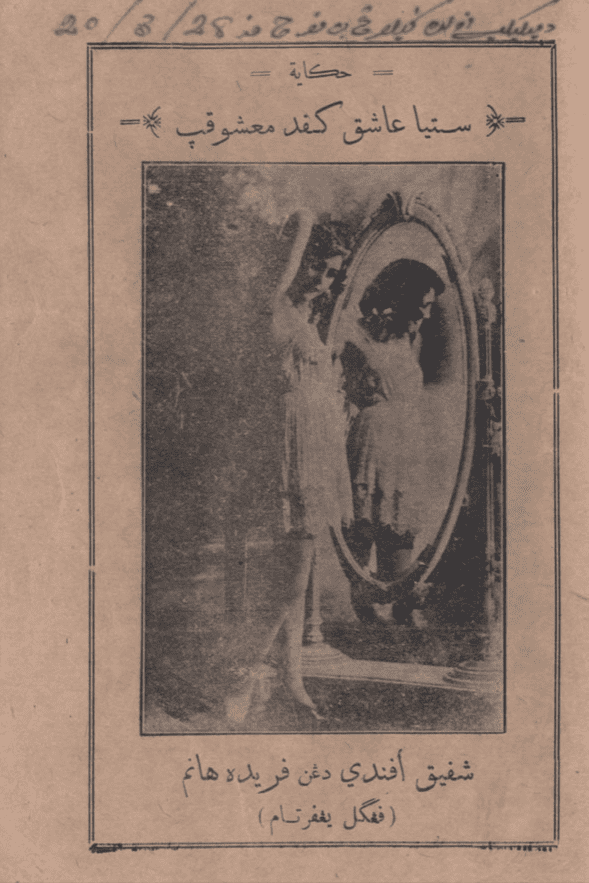

On the cover of the second edition of a Malay novel released in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, the reader encounters a photographic illustration of a woman standing in front of a freestanding oval-shaped full-length mirror. She has turned her body away from the mirror and toward the reader. With her right arm above her head, she strikes an alluring pose. It is a beguiling image, for though her gaze is cast downward, one senses there is nothing demure in her not confronting our intrusive gaze. After all, in exuding both nonchalance and self-awareness, the subject is confident of her attraction and power over readers.

This is doubly so, since the mirror almost fully captures her bodily reflection. In turn, the mirror serves as an important specular narrative device, for in this instance, the existential and moral conundrums faced by a Malay author in early twentieth-century Penang, where the novel was published, is refracted onto and projected against a more tantalizing and exotic backdrop: that of fin-de-siècle Cairo, Egypt.1Syed Sheikh Syed Ahmad al-Hadi, Hikayat setia asyik kepada masyuknya, atau, Syafik Efendi dengan Faridah Hanum [The Story Concerning the Loyalty of One’s Desire Toward Its Fulfillment, or, Syafik Efendi and Faridah Hanum], 2 vols. (Penang: Jelutong Press, 1925 and 1926). The protagonists of this occidental melodrama and romance are named in the second part of the novel’s double title, Syafik Efendi dengan Faridah Hanom (Syafik Efendi and Faridah Hanom). Over time, the best-selling novel would be better known in the annals of Malay literature as Hikayat Faridah Hanom (The Story of Faridah Hanom).

Yet, as risqué as the enterprise may seem, its author, Syed Sheikh Syed Ahmad al-Hadi, came from a respectable background and is better known as an ardent supporter of Islamic reformism and women’s rights. Though born in Malacca, Syed Sheikh was of Arab-Peranakan descent and spent considerable time in Riau before furthering his education at Cairo’s Al-Azhar University. In the course of this essay, I hope to suggest that these subject positions are not mutually exclusive. If they appear to contradict one another, it is only because we assume that the underlying structural principle of culture is reducibly a binary.2Kirk M. Endicott, An Analysis of Malay Magic (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 179. Endicott suggests that cultural practice in the Malay archipelago did not fit into the dyadic model. Rather, in possessing a triadic structure, it is able to “help preserve, in the face of the conflicting qualities and associations of things brought on by massive cultural syncretism, the dual mode of distinction that so efficiently marks boundaries. . . . In this regard, the triad exceeds the dyad in complexity far more than the difference between the quantities ‘two’ and ‘three’ suggest.”

By locating culture and identity as negotiation-driven rather than essentialist, I hope to call into question the dominant ways in which desire is read in relation to the subject who is psychoanalytically conflictual and repressed. A different kind of psychical scaffolding, one that facilitates the configuration of a modern subjectivity, is suggested by the allegorical title of Hikayat setia asyik kepada maksyuknya, which translates as “The Story Concerning the Loyalty of One’s Desire Toward Its Fulfillment.” Unlike in psychoanalysis, it isn’t assumed here that behind the idealized rational person is a barely containable roiling sea of destructive conflicting forces internal to his (and the operative “he” is typically the primary subject pronoun) fragile makeup, threatening to undo the modern subject’s facade of coherence.3See Hal Foster, “Primitive Scenes,” in Prosthetic Gods (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 29.

If desire has a role to play at all, it is framed principally through the lens of kesedaran (realization). Realization in this sense is a morally existential question, centered on political, cultural, and economic dispossession of local communities during the height of European imperialism. Though the characteristics of this form of realization have received a wide range of exegesis in the fields of literature; social, economic, and political history; and ethno-nationalist politics, the idea and movement have, by and large, been primarily examined through textual discourses.4Not many take the October gang seriously today, which is a shame. This is partly because of their own hubris, but I have always found the best in them and still turn to Art Since 1900 as an introduction to the grandiloquence of that generation’s sensibility and scholastic temerity. The introductory chapter to psychoanalysis doesn’t disappoint. See Hal Foster et al., Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004). In contrast to these widely perused textual sources, the visualities of sense perception are seldom discussed. Existing scholarship tends to brush aside these contradictions faced by early twentieth-century Malay authors in favor of sociopolitical contextualization.

In exploring a series of visual experiments undertaken along the Strait of Malacca that paralleled the political trajectory of kesedaran, it is the near irreconcilable difference between an idealized political vision and a sensually materialistic consumer culture that makes these visual experiments fertile sites in which to explore an aesthetics of kesedaran—whereby what is sensed captures a cosmopolitan field of vision, over and beyond the textual appeal that carries sentiments of being left behind or of cultural decline. In focusing on the aesthetics of kesadaran, I suggest here that desire points to the possibilities of fulfillment rather than to a perpetual deferment of promise or the conflictual tension between modernity and religion.

A Delightful Subject

Who is the modern subject on the cover of Syed Sheikh’s novel? The photograph chosen for the cover of the Hikayat provides an entry point. Scholars have remarked that the photographs chosen to accompany the story are likely celebrity portraits clipped from magazines. Excised from their original contexts, they have been pressed into service in a different narrative universe. In printed form, the photographed woman standing in for Faridah Hanom is the final outcome in a chain of reconfiguration. It is this chain that connects Syed Sheikh’s repurposing of the photographic image in his 1925–26 novel to his earlier exposure to the literary and social activities of the Rusydiyah Club (“Right Guidance” Club) on the Penyengat island of Riau, and the collage experiments of Raja Haji Abdullah and Khadijah Terong, a husband-and-wife literati duo from Penyengat Island, in their surviving manuscripts from 1902–11. It is along this chain that I will make the case for an archipelagic modernism.

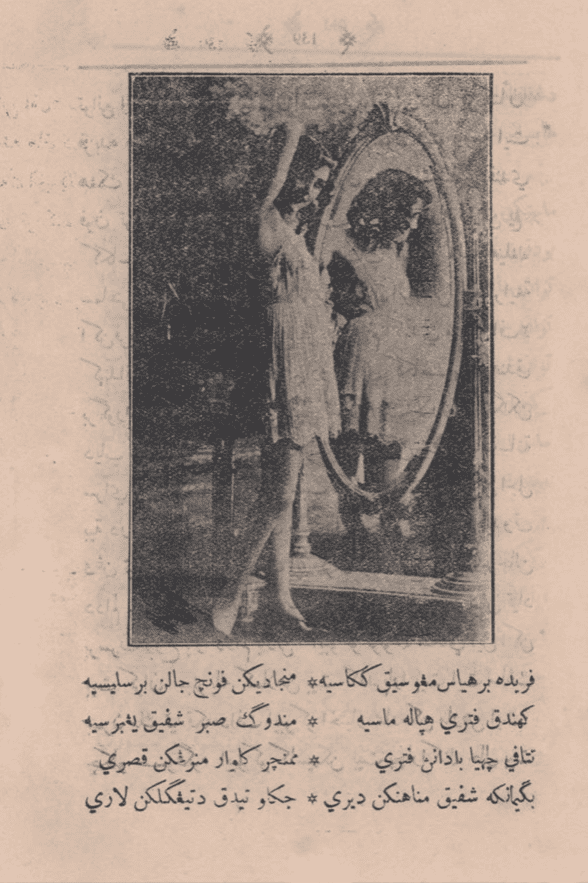

The photographic image makes a second appearance in the novel as an insert complemented by a syair verse, a poetry genre that emerged in the seventeenth century. Though seemingly lighthearted on the first read, the syair was typically written by Sufi teachers who traded in relatable imagery and metaphors while communicating mystical spiritual truths.5See Liaw Yock Fang, “Poetic Forms: Pantun and Syair,” in A History of Classical Malay Literature, trans. Razif Bahari and Harry Aveling (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2013), 442–90. By the nineteenth century, it was the favorite form to accommodate a wide range of expressions, from biting social observation and fantastical fairy tales to timely customary advice and propaganda speeches.6See Mulaika Hijjas, “Not Just Fryers of Bananas and Sweet Potatoes: Literate and Literary Women in the Nineteenth-Century Malay World,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 41, no. 1 (February 2010): 153–72; and Jan van der Putten, “On the edge of a tradition: Some prolegomena to paratexts in Malay rental manuscripts,” Indonesia and the Malay World 45, no. 132 (2017), 179–99. Its AAAA rhyme scheme made composing relatively easy. In this sense, the comic relief in the verse that accompanies the image in question bears closer examination:

Faridah berhias mengusik kekasih, menjadikan punca jalan berselisih;

Kehendak puteri hanyalah masih, menduga sabar Shafiq yang bersih;

Tetapi cahaya badannya puteri, memancar keluar menerangkan keseri;

Bagaimanakah Shafiq menahankan diri, jikalau tidak ditinggalkan lari.7Syed Syaikh, Hikayat setia asyik kepada masyuknya,138–39. “Faridah dresses up to tempt her lover, causing him to feel uneasy; / Her design had a purpose in mind, to test the limits of Syafik’s purity; / But the light from her body, glows with splendor and clarity; / How then is Syafik able to resist, if he doesn’t take off immediately?”

In this rather bawdy scenario, a very different kind of masculine subject position can be deciphered, as compared to the Ur-moment of modernism, in which Pablo Picasso’s encounter with the women at a brothel in Avignon led not only to an existential crisis, but also to an aggressive response that devises planar deconstruction in the ground-figure relationship as protective formula.

On the other hand, the radiating light of Faridah seems to refer to a common religious trope that purity of conduct is legible through visible signs such as the effulgent light of saintliness. While Faridah’s radiance can be seen as threatening to the masculine subject, Syafik’s succumbing to beauty is seen as ameliorating rather than entropic.

One sees a playful deployment of this trope for comedic effect, especially when the word keseri is used to depict the moment of revelation. “Keseri” is also a homophone for a type of sweet delicacy—a dessert, or “kuih,” originating from South Asia made with suji flour and fruits for flavor and color. “Keseri” also sounds like “koshary,” an Egyptian street food staple comprising a mixture of rice, lentils, and macaroni that emerged sometime in the mid-nineteenth century. While the distinct Italian inflection is inescapable, the spice and flavor of the dish point to its origin in the khichri, a South Asian rice-and-lentil dish.

In this choice of word to qualify Faridah’s radiance, Syed Sheikh stretches the qualitative marker for the effulgence of Godly radiance, making the word occupy an expansive cultural spectrum. In doing so, there isn’t a need for a culturally specific meaning to cancel out other associations. It is precisely this plurality that sustained and defined the cosmopolitan contours of Penang, the port city in which Syed Sheik set up his publishing venture, and turned the troubles and anxieties of the modern on its head, commenting on the power of wish fulfillment. This relishing play of words illuminates the pleasurable delight the author took in the sensual reconfiguration of the cultural resources at his disposal.

By the fin de siècle, modernizing influences from both Europe and Middle Eastern Islam electrified Raja Haji Ali’s descendants on the Riau Islands.8Virginia Matheson, “Pulau Penyengat: Nineteenth Century Islamic Centre of Riau, Archipel 37 (1989): 153–72. Those who wielded the pen soon established the Rusydiyah Club, where the dissemination of new ideas and consolidation of old knowledge were carried out from 1895 to 1905.9Timothy P. Barnard, “Taman Penghiburan: Entertainment and the Riau Elite in the Late 19th Century,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 67, no. 2 (267) (1994): 17–46. Gradually, this gave rise to a new sensibility of watan (homeland), and this sentiment of belonging emboldened the political resistance to Dutch rule. By 1911, as a punitive response to this rising sentiment, the Dutch colonial government lay siege to the royal court and deposed the crown prince and supporting members of the Rusydiyah Club on the grounds of treason. Following Dutch annexation of the Riau archipelago, there was an exodus, and many settled in either Johor or Singapore.10See “Detail from Map of Asia used by A. R. Falck in London in 1824 [. . .],” in On Paper: Singapore before 1867 (Singapore: National Library Board), 81. Though not a member of the Riau aristocracy, Syed Sheikh found his way into this cultural milieu. However, during the time of dispersal, he chose to settle farther north on the island of Penang.

It was against this larger historical backdrop that a number of surviving manuscripts were written during the first decade of the twentieth century. These works register, in particular, novel attempts at repurposing photographic images, clipped largely from European magazines and newspapers. All of these images have been taped into manuscripts, and each one is composed within a hand-drawn border frame. Moreover, many of these manuscripts are formatted as printed books, and therefore publicly available, even in cases in which their content suggests private use. The repurposing of photographic images has then been enhanced by additional illustrations or through collage,11Wendy Mukherjee, “The love magic of Khadijah Terong of Pulau Penyengat,” RIMA: Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs 31, no. 2 (December 1997): 29–46. Special thanks to Show Yingxin for securing me a copy. See also Ding Choo Ming’s transcription: “Khatijah Terung dengan karyanya Perhimpunan Gunawan Bagi Laki-Laki dan Perempuan (bahagian 1)” [Khatijah Terung and Her Work Useful Grimoire for Men and Women (part 1)]” (Presentation at the MANASSA International Symposium at Andalas University, Padang Sumatra, July 28–31, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/30595365/Khatijah_Terung_dengan_karyanya_Perhimpunan_Gunawan_Bagi_Laki_Laki_dan_Perempuan_bahagian_1_. reflecting an increasingly visual turn, one in which images circulated freely through print culture and were often consumed creatively through personalized annotations.12Jan van der Putten and Farouk Yahya have made great inroads by situating the image within cultural paradigms so that interpretations can be advanced. SeeJan van der Putten, “Tanggapan Pengarang Riau terhadap Budaya Bandar di Pulau Jiran” [Responses of an Author in Riau toward the Urban Culture in a Neighboring City], SARI 25 (2007): 127–48; and Farouk Yahya, Magic and Divination in Malay Illustrated Manuscripts (Leiden: Brill, [2016]), 240–41.

Rosalind Krauss makes a case that collage’s “capacity of ‘speaking about’ depends on the ability of each collage element to function as the material signifier for a signified that is its opposite: a presence whose referent is an absent meaning, meaningful only in its absence.”13Rosalind Krauss, “In the Name of Picasso,” October 16, Art World Follies (Spring 1981): 20. If Raja Haji Abdullah’s European counterparts were primarily concerned with circumventing representational constraints that emerged from a pictorial convention in which recessional depth is projected through the canvas, the manuscript book offers a different set of semiological challenges—and the gambit took off in a different direction.

This is a different unit of analysis compared to the singularity of a work on canvas, where meaning—no matter how pregnant a painting may be—is sufficiently conditioned and contained by its parergon, that is, the four sides that delimit the pictorial field. On the other hand, the framing device of the collage operation in Malay printed books is a relay device, in which signification operates in reference to the preceding image and in anticipation of the one to come—not unlike the AAAA rhyme scheme of the syair and the narrative structure of the novel, both of which are deployed in the Hikayat. Here the hand-drawn frame locates the formal challenge in relation to the printed book. In this sense, rather than containment, it provides a visual connection, creating a linear narrative that forms the skeletal structure of the book.

At play is an adaptive recontextualization of photographs and imagery found in European print culture, giving them another purpose and alternate meaning through a process of artistic intervention. Syed Sheikh’s exploration of the remediated found photographic image in print was contemporaneous with Pablo Picasso’s experimentation with the figure-ground relationship through the use of collage on canvas. For Picasso, the use of print media in his collages led to analytical cubism. In the case of the Hikayat, living under the shadows of colonialism, printed media showed up as visual detritus that could be adapted purposefully in a local knowledge system.

The image of Faridah suggests that modernism in Southeast Asia possesses its own cosmopolitan trajectory. This story does not have to be a parade of pioneering “father” figures, whose métier and worth are often described by the association of influential European art movements. Instead, contemporaneous with the beginnings of modernism in Europe, was a whole range of creative impulses in other parts of the world that shared modernism’s interest in experimental forms.

In previous scholarly interpretations of the repurposing of images in early printed Malay books, the meaning in these images is primarily explained by securing evidence in sections of texts that share similar imagery.14See, for example, Jan van der Putten, “Abdullah Munsyi and the missionaries,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 162, no. 4 (2006), 407–40; and Annabel Teh Gallop, “Early Malay Printing: An Introduction to the British Library Collections,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 63, no. 1 (1990), 85–124. In this argument, images are primarily regarded as illustrations of narrative content that is more authentically captured through the textual record. Instead of falling back on the ideologically heteronormative compact of these prior debates, I draw interpretive legitimacy from the image rather than the text.

Gambar’s Specular Discourse

Faridah’s mirrored image points to the emergence of gambar (image) as a unique discursive operation that draws on customary ideas of power in the visual form to make sense of the expanding horizons of a changed world.15Thanavi Chotpradit et al., “Terminologies of ‘Modern’ and ‘Contemporary’ ‘Art’ in Southeast Asia’s Vernacular Languages: Indonesian, Javanese, Khmer, Lao, Malay, Myanmar/Burmese, Tagalog/Filipino, Thai and Vietnamese,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 2, no. 2 (October 2018): 65–195, DOI: 10.1353/sen.2018.0015. Though it is iconographic and reflective, the mirror is also a pictorial device that is highly reflexive, enabling the emergence of a modern self.

To be sure, the use of full-length mirrors in portrait photography had become a convention by the 1920s. Nevertheless, art historian Wu Hung suggests that it is a convention encoded with new meaning and purpose.16Wu Hung, “Birth of the Self and the Nation: Cutting the Queue,” in Zooming In: Histories of Photography in China (London: Reaktion Books, 2016), 85–124. In Wu Hung’s reading of queue-cutting portraits, he suggests they “linked two histories, one national and the other personal, while generating tension between the two.” I suggest that a queer operation is also at play in the recurrence of specular tropes in Malay printed books, in which the mirror signposts a subject’s becoming rather than its foregone conclusion. In this way, I want to re-center shape-shifting, boundary-negotiating, and relation-building as the cultural ethos encapsulated by the engendered subject of modernism. Central to this formal enchantment is the concept of main or “play,” which, as used in Malay ritual theater, suggests that there are parallels between the abilities to shape-shift and to create contacts through the elective forms of affinity.17Henk Maier, “‘We Are Playing Relatives’: Riau, the Cradle of Reality and Hybridity,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 153, no. 4, Riau in Transition (1997): 672–98. Through main, one loses the self to become another being or assume another form.

The ritual of seduction that entreats the reader in the image of Faridah can be located within a complex moral universe emerging at the height of imperialism. Faridah cuts a figure that is neither dismissive, righteous, nor prudishly bashful, neither sexually wanton nor socially ingratiating. In this sense, the mirror she stands in front of is the specular apparatus of accommodation—showing Faridah’s double, a double that could be anywhere else in the world. In becoming a composite of the world, rather than made schizophrenic, Faridah’s reflection signposts the wholeness of a shared condition. In doing so, she becomes relatable to modern subjects in the making across the world, searching for a compact outside of what Aníbal Quijano has called a “colonial matrix of power.”18Aníbal Quijano and Michael Ennis, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America,” Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000), 533–80.

Yet, the image technology discussed here is not a phenomenon of late twentieth-century “contemporary art.” Krauss suggests that the linguistic power of collage enables communication through the play of absence. She also contends that attending to a crisis in representation could locate a protohistory of postmodernism.19Krauss, “In the Name of Picasso.” In tracking the generative plasticity of images that circulated promiscuously along the volatile currents of global colonial capitalism, a different origin story of modernism might just be the very “contemporaneous alternative to modernism” that Krauss belabors over the anxieties faced by Picasso.20Ibid., 21.

The waves of desire that underlie such yearning for form didn’t always lead one down a path of anguish or delirium. If our encounter with the woman in front of the mirror was initially an intrusive one, then I hope this essay shows that the gambar of the modern woman finds fulfillment when desire is not defined as a libidinal product that leads to a schizophrenic sense of deficiency. Desire is ultimately loyal to its fulfillment.

Moreover, it fulfills the plea made by film scholar May Adadol Ingawanij for a decolonized art history that playfully prospects, “What if you try to live by playing with using and misusing whatever ideas, speculations and concepts, originating from wherever and passing through whichever paths . . . to push further into somewhere as yet undefined?”21May Adadol Ingawanij, “Making Line and Medium,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 3, no. 1 (March 2019), https://muse.jhu.edu/article/721043.

Faridah is not a narcissist absorbed in self-regard. Her coy knowledge, which simultaneously feigns meekness, is the only clue that whatever we have to say about her is always deficient: we can never fully know her or tell her how to behave. This is the postmodern as postcolonial. Over and beyond the author’s intention, or the demands of national art history and the borders it seeks to police, Faridah as gambar exemplifies the conceptual cunning of an archipelagic modernism. She radiates with liquid effulgence. She is in control of her narrative.

- 1Syed Sheikh Syed Ahmad al-Hadi, Hikayat setia asyik kepada masyuknya, atau, Syafik Efendi dengan Faridah Hanum [The Story Concerning the Loyalty of One’s Desire Toward Its Fulfillment, or, Syafik Efendi and Faridah Hanum], 2 vols. (Penang: Jelutong Press, 1925 and 1926).

- 2Kirk M. Endicott, An Analysis of Malay Magic (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 179. Endicott suggests that cultural practice in the Malay archipelago did not fit into the dyadic model. Rather, in possessing a triadic structure, it is able to “help preserve, in the face of the conflicting qualities and associations of things brought on by massive cultural syncretism, the dual mode of distinction that so efficiently marks boundaries. . . . In this regard, the triad exceeds the dyad in complexity far more than the difference between the quantities ‘two’ and ‘three’ suggest.”

- 3See Hal Foster, “Primitive Scenes,” in Prosthetic Gods (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 29.

- 4Not many take the October gang seriously today, which is a shame. This is partly because of their own hubris, but I have always found the best in them and still turn to Art Since 1900 as an introduction to the grandiloquence of that generation’s sensibility and scholastic temerity. The introductory chapter to psychoanalysis doesn’t disappoint. See Hal Foster et al., Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004).

- 5See Liaw Yock Fang, “Poetic Forms: Pantun and Syair,” in A History of Classical Malay Literature, trans. Razif Bahari and Harry Aveling (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2013), 442–90.

- 6See Mulaika Hijjas, “Not Just Fryers of Bananas and Sweet Potatoes: Literate and Literary Women in the Nineteenth-Century Malay World,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 41, no. 1 (February 2010): 153–72; and Jan van der Putten, “On the edge of a tradition: Some prolegomena to paratexts in Malay rental manuscripts,” Indonesia and the Malay World 45, no. 132 (2017), 179–99.

- 7Syed Syaikh, Hikayat setia asyik kepada masyuknya,138–39. “Faridah dresses up to tempt her lover, causing him to feel uneasy; / Her design had a purpose in mind, to test the limits of Syafik’s purity; / But the light from her body, glows with splendor and clarity; / How then is Syafik able to resist, if he doesn’t take off immediately?”

- 8Virginia Matheson, “Pulau Penyengat: Nineteenth Century Islamic Centre of Riau, Archipel 37 (1989): 153–72.

- 9Timothy P. Barnard, “Taman Penghiburan: Entertainment and the Riau Elite in the Late 19th Century,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 67, no. 2 (267) (1994): 17–46.

- 10See “Detail from Map of Asia used by A. R. Falck in London in 1824 [. . .],” in On Paper: Singapore before 1867 (Singapore: National Library Board), 81.

- 11Wendy Mukherjee, “The love magic of Khadijah Terong of Pulau Penyengat,” RIMA: Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs 31, no. 2 (December 1997): 29–46. Special thanks to Show Yingxin for securing me a copy. See also Ding Choo Ming’s transcription: “Khatijah Terung dengan karyanya Perhimpunan Gunawan Bagi Laki-Laki dan Perempuan (bahagian 1)” [Khatijah Terung and Her Work Useful Grimoire for Men and Women (part 1)]” (Presentation at the MANASSA International Symposium at Andalas University, Padang Sumatra, July 28–31, 2011), https://www.academia.edu/30595365/Khatijah_Terung_dengan_karyanya_Perhimpunan_Gunawan_Bagi_Laki_Laki_dan_Perempuan_bahagian_1_.

- 12Jan van der Putten and Farouk Yahya have made great inroads by situating the image within cultural paradigms so that interpretations can be advanced. SeeJan van der Putten, “Tanggapan Pengarang Riau terhadap Budaya Bandar di Pulau Jiran” [Responses of an Author in Riau toward the Urban Culture in a Neighboring City], SARI 25 (2007): 127–48; and Farouk Yahya, Magic and Divination in Malay Illustrated Manuscripts (Leiden: Brill, [2016]), 240–41.

- 13Rosalind Krauss, “In the Name of Picasso,” October 16, Art World Follies (Spring 1981): 20.

- 14See, for example, Jan van der Putten, “Abdullah Munsyi and the missionaries,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 162, no. 4 (2006), 407–40; and Annabel Teh Gallop, “Early Malay Printing: An Introduction to the British Library Collections,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 63, no. 1 (1990), 85–124.

- 15Thanavi Chotpradit et al., “Terminologies of ‘Modern’ and ‘Contemporary’ ‘Art’ in Southeast Asia’s Vernacular Languages: Indonesian, Javanese, Khmer, Lao, Malay, Myanmar/Burmese, Tagalog/Filipino, Thai and Vietnamese,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 2, no. 2 (October 2018): 65–195, DOI: 10.1353/sen.2018.0015.

- 16Wu Hung, “Birth of the Self and the Nation: Cutting the Queue,” in Zooming In: Histories of Photography in China (London: Reaktion Books, 2016), 85–124. In Wu Hung’s reading of queue-cutting portraits, he suggests they “linked two histories, one national and the other personal, while generating tension between the two.”

- 17Henk Maier, “‘We Are Playing Relatives’: Riau, the Cradle of Reality and Hybridity,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 153, no. 4, Riau in Transition (1997): 672–98.

- 18Aníbal Quijano and Michael Ennis, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America,” Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000), 533–80.

- 19Krauss, “In the Name of Picasso.”

- 20Ibid., 21.

- 21May Adadol Ingawanij, “Making Line and Medium,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 3, no. 1 (March 2019), https://muse.jhu.edu/article/721043.