This year’s C-MAP seminar series, Transversal Orientations, comprised four panels that took place on Zoom in June 2021. Textual responses to each of the panels were commissioned to further discussion about the seminar’s central concerns. In this essay, Dr. Chairat Polmuk (Lecturer, Department of Thai, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok) reflects on Looking Sideways, the first panel in the seminar series featuring Sorawit Songsataya, Corina L. Apostol, and Ruth Simbao.

In the 1980s, pollination was a metaphor for the Thai literary and male homoerotic magazine Gaysorn Prasopkan to figure notions of kinship and futurity. The title of the publication, which translates as “pollen (gaysorn) of experience (prasopkan),” stresses how the transference of intimate stories––real or imagined––is central to the sustenance of non-heterosexual matrixes of intimacy. While we might problematize the use of botanical metaphors as conceptually confined to what queer theorist Lee Edelman has called “reproductive futurism,”1Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 2–3. Gaysorn Prasopkan offers a distinct portrait of an efflorescent gay culture shaped by the poetic invocation of floral beauty, fragility, and promiscuity. Suntisuk Prabunya aptly reads the magazine as constitutive of 1980s Thailand’s “queer intimate public,” borrowing from Lauren Berlant’s conceptualization of an intimate public sphere as a “porous, affective scene of identification among strangers that promises a certain experience of belonging and provides a complex of consolation, confirmation, discipline, and discussion about how to live as an x.”2Suntisuk Prabunya, “‘His Wounds, My Wounds’: Melancholic Community and Queer Intimate Public in Gaysorn Prasobkarn Magazine” (Council on Thai Studies Annual Meeting, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, November 15, 2020). The original quote is from Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), viii. If we are to take the magazine’s plant symbolism seriously, we might further ask: How can we understand a queer experience of belonging as a space between rootedness and mobility? Like the pollen of immobile flowers traversing only with the force of the wind or the help of insects, queer intimacy points to an experience of orientation as much as disorientation.3For a discussion of orientation, both in the domains of phenomenology and sexuality, see Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

Secretly reading Gaysorn Prasopkan under a blanket on a rainy day would evoke a perfect coming-of-age nostalgia, but the context of my encounter with the magazine was instead quite recent and pedagogical. I was searching––desperately and apparently in all the wrong places––for “queer poetry” to offer to the modern Thai poetry class I was teaching in early 2021. In this class, the students and I read impassioned poems by left-wing writers who yearned for freedom under the authoritarian regimes of the 1960s and 1970s.4For a recent work on Thai poetry and the cultural history of the Cold War, see Arnika Fuhrmann, Teardrops of Time: Buddhist Aesthetics in the Poetry of Angkarn Kallayanapong (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2020). We encountered references to botanical metaphors to rewrite the roles of women during such political struggles, specifically in the celebrated poem “Ahangkarn Khong Dokmai” (“The Defiance of a Flower”), which was penned by poet and former student activist Chiranan Pitpreecha.5Famous lines from the poem read: “A flower has sharp thorns / Not bursting into bloom for an admirer / She blossoms to raise / The glory of the earth.” Translation by Rachel Harrison for Southbank Centre’s Poetry Parnassus festival, 2012, https://www.nationalpoetrylibrary.org.uk/online-poetry/poems/defiance-flower. The publication of her collected poems Baimai Thi Hai Pai (The Missing Leaf) in the late 1980s paved the way for the flourishing of feminist voices in the generations that followed. Thai poetry on queerness, however, is simply nonexistent in academic and popular discourses. To find it means to build one’s own archive for a queer literary history of Thailand that has not yet been written.

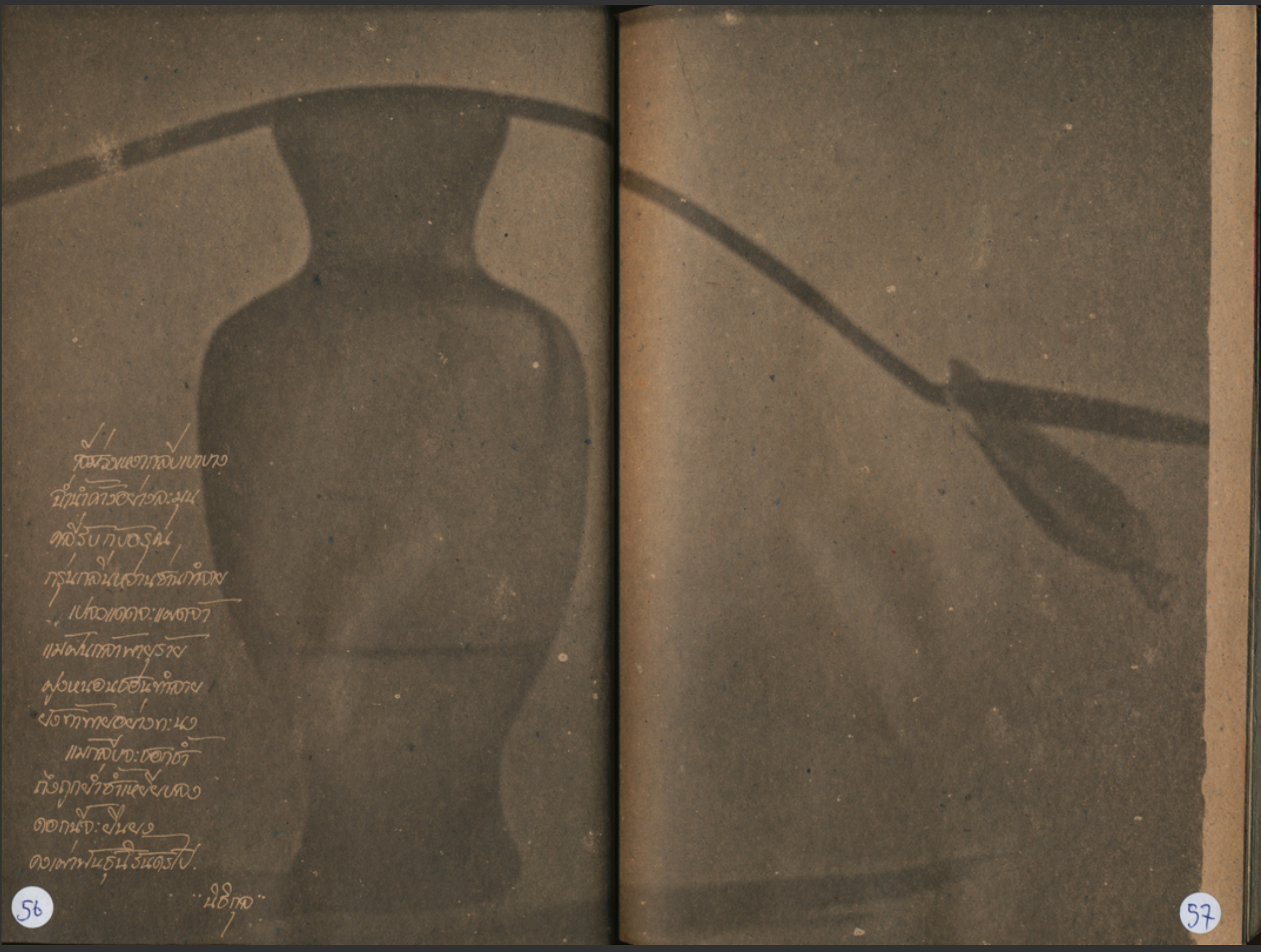

It was only at the advice of my brilliant student Suntisuk Prabunya that Gaysorn Prasopkan came to my attention. Published in 1985–86 by a commercial printing company, this short-lived magazine usually features images of half-naked male models on its covers and devotes its approximately 130 pages to personal erotic accounts, short stories, poems, bawdy cartoons, and translations of Western fiction (including E. M. Forster’s homosexual bildungsroman Maurice, and Patricia Nell Warren’s gay sports romance The Front Runner). In all eleven issues of Gaysorn Prasopkan, now fully digitized and made available online as part of the Thai Rainbow Archive project within the Endangered Archives Programme of the British Museum, the poetry section offers the most satisfying illustration of the magazine’s symbolic and affective investment in flowers. A handwritten, untitled poem by Nithikul, for instance, both laments and celebrates the flowerlike fragility of queerness. Printed alongside a painting of a vase that supports the single stalk of a flower arranged at a strange, oblique angle (fig. 1), the poem reads:

Delicate, purple petals of loneliness

Gently covered with dew

Unfold themselves at dawn

Exuding sweet fragrance.

Despite the burning sun

And heavy rain and violent storm

Or hordes of ravaging worms

The flower defiantly persists.

Although its petals are bruised

Being trampled on repeatedly

This flower will flourish

And continue its species eternally.6Nithikul, Untitled, Gaysorn Prasopkan 1, no. 6 (1985): 56. My translation.

Through the poetics of the flower, I threaded together the feminist literary movement in the 1980s and the contemporary burgeoning of a queer literary culture fueled by print capitalism, rapid urbanization, and economic growth in the aftermath of the Cold War.7Peter A. Jackson discusses the emergence of commercial Thai male homoerotic magazines in the 1980s such as Mithuna, Mithuna Junior,and Neon in relation to print capitalism and global queer culture in Peter A. Jackson, “Capitalism and Global Queering: National Markets, Parallels Among Sexual Cultures, and Multiple Queer Modernities,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 15, no. 3 (2009): 357–95.

I decided to spice up assigned readings of already colorful poems on femininity and queer sexuality through a new thematic focus and interpretive strategy: the complex relationship between poetry and art. Thinking it would be a fun exercise for my students, I hosted an online workshop (due to the pandemic) in which I invited the young and promising Thai artist Naraphat Sakarthornsap to create artworks inspired by a selection of five poems on gender and sexuality by female and gay poets, including those from Gaysorn Prasopkan. During the workshop, Naraphat shared a story about his artistic response to the poems. For almost a decade now, flowers have been vital to Naraphat’s works and his experience with his sexual identity. In the photographic series titled Ignorant Bond (2017–19), Naraphat revisits his childhood home and memories through flower arrangements. Mundane domestic objects such as a toilet bowl and corded home telephone (fig. 2) are adorned with different kinds of flowers. While the work is not explicitly “queer,” its keen attentiveness to everyday scenes of attachment and longing captures the quotidian and ephemeral characteristics of a queer archive. As Ann Cvetkovich has observed about her research experience at the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives in California: “To touch these objects is to receive a personal message from June about what she thought was important. Ephemeral objects have that power––gesturing to affective meanings that are attached to objects but not fully present in them, while also making immaterial ephemeralities material.”8Ann Cvetkovich, “Ephemera,” in Lexicon for an Affective Archive, eds. Giulia Palladini and Marco Pustianaz (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2017), 179–83. We might also think of flower arranging as an act of queer reorientation, as transforming the familiar––and familial––domestic space into an oneiric landscape of queer belonging in order to feel at home again. Flowers, in Naraphat’s playful yet contemplative practice of adornment, beckon us to ponder the rooted yet unlocatable quality of queerness. Like the ornamental flowers, queer attachments to the domestic space and objects of sensory memory are both artificial and candid.

After the workshop, the students seemed disoriented, but in a good way. They were assigned to create an “artwork” from their own readings of other poems on female and queer sexualities. All the works I received (there were about twenty-five students enrolled) displayed the students’ openness to poetry beyond our trained habit of paranoid reading––a critique of representational failures or ideological ruptures in literary texts.9See Eve Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–51. Regardless of the success (or failure) of this pedagogical experiment, queer botanical poetics allowed the class to experience what literary scholar Rita Felski has called the “transtemporal liveliness of texts” and to understand how interpretation can constitute a powerful “mode of attachment” rather than detached rumination.10Rita Felski, “Context Stinks!” New Literary History 42, no. 4 (Autumn 2011): 573–91. In other words, interpretation in my inter-art approach to a poetry class is no different from what the 1980s Thai gay community would have called the pollination of experience.

***

I found the transtemporal, as well as transregional, liveliness of accounts on flowers most striking in the “Looking Sideways” panel. In Sorawit Songsataya’s presentation on their artistic practice, images of dried flowers adorning a handcrafted Thai kite (fig. 3) in the 2019 mixed-media installation Jupiter, for example, provide a subtle paratext for the artist’s meditation on queer and diasporic experiences. Drawing from both Thai and Māori indigenous beliefs regarding the intermediary roles of the kite, Sorawit’s artwork accentuates the notion of in-betweenness in relation to expressions of dislocation, transculturation, and gender identity. The floral textile decoration, according to the artist, complicates an association of kites and craftmanship with masculinity in the Thai cultural logics and, thus, invites a feminist and queer reading of such crafted objects. In this regard, we might understand the work as a dramatization of queer transversality through an allegorical staging of pollination. Together with the installation’s central six-channel digital video of kites, windmills, and fairground attractions that explores the animating force of the wind (a “natural pollinator” in Sorawit’s words11Sorawit Songsataya, “Looking Sideways” (panel discussion, Transversal Orientations, Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) seminar, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 2, 2021).), Jupiter’s playful invocation of pollination further expands narratives of boundary crossing to include complex relations between human and non-human, life and nonlife.

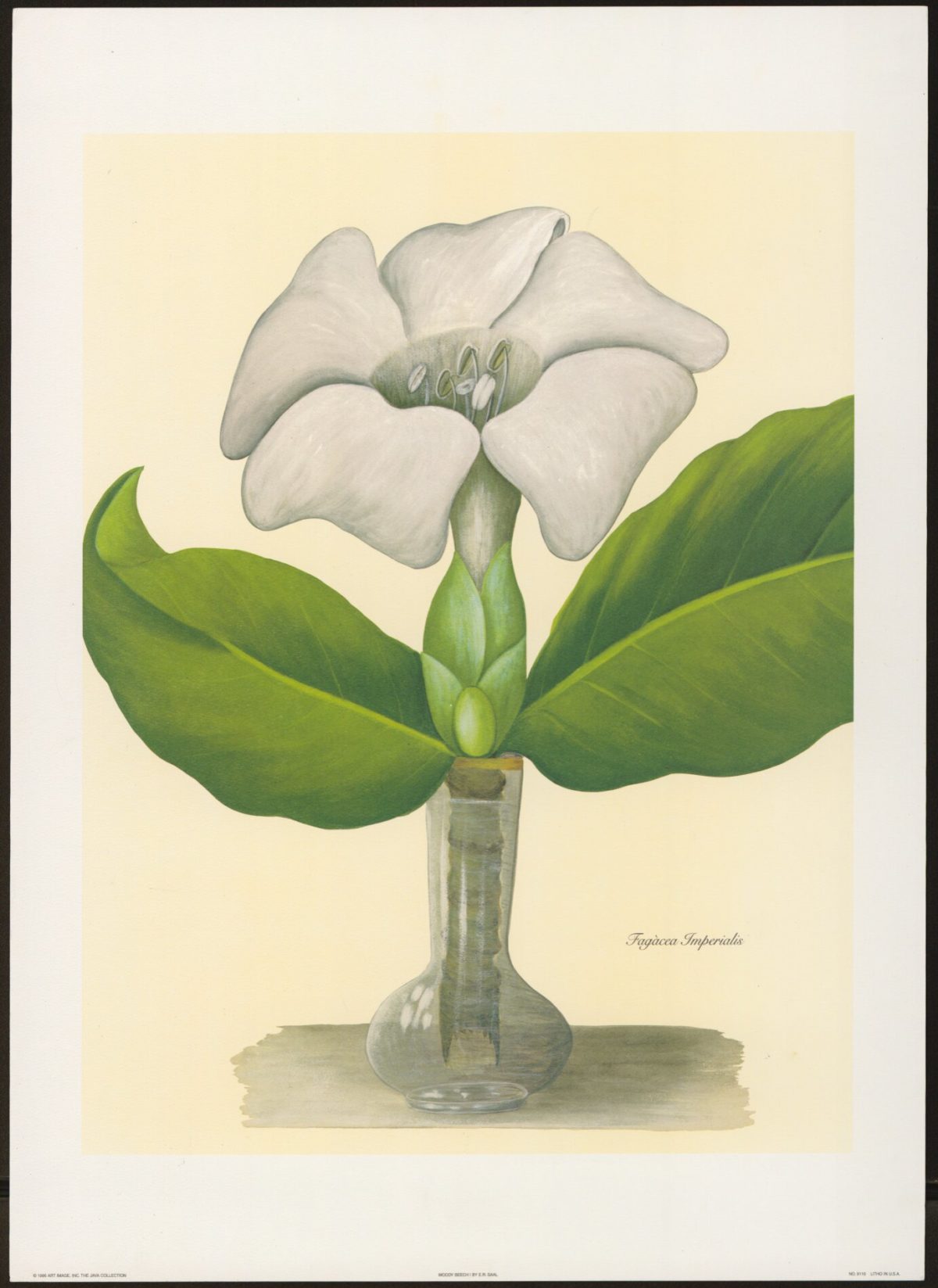

Following the lead of flowers, the orchid to be precise, Corina Apostol brought an ecofeminist perspective to bear on the forgotten legacy of Estonian botanical artist and explorer Emilie Rosalie Saal (1871–1954). Situating Saal’s life and works within the European quest (and craze) for tropical orchids, Apostol related an entangled history of colonial exploitation, biological sciences, and artistic creation. While Saal’s artistic oeuvre, mostly produced during her years in colonial Indonesia, is inseparable from a harrowing account of colonial ecological destruction, her piecemeal biography offers glimpses of a gendered landscape of botanical art under colonial rule.12In her anthropological studies of colonial Indonesia, Ann Laura Stoler has noted the need to shift away from viewing colonial elites as “homogenous communities of common interests” and to rethink the consolidation of colonial authority through notions of intimacy, gender difference, and sexual regulation. See Ann Laura Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 43. In engendering the Dutch–Indonesian botanical history, Apostol’s research also highlights the transtemporal aspect of orchidelirium––the floral madness that left its colonial imprints on Indonesian narratives of botanical heritage.

The accounts that I have been producing and reproducing in this text reveal the flower’s potential to forge affective relations across time and space. The flower, as a central figure of these narratives and artistic practices, generates a kind of affective attachment that is akin to what Sara Ahmed describes as the “stickiness” of emotion––the enabling power of affective value that binds the psychic and the social, the collective and individual bodies.13Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (New York: Routledge, 2004). Perhaps, then, we might further complicate the poetic invocation of flowers to create transtemporal and transregional layers of historical experiences through Ruth Simbao’s notion of the “stickiness of being.” In her discussion of Myriam Dao’s artistic practice, Simbao problematizes the conventional understanding of solidarity, specifically in the context of Afro-Asian anticolonial movements. Paying close attention to the artist’s experiment with photo booth portraits of her father in the polyptych titled Nos ancêtres les Gaulois (Our Ancestors the Gauls), Simbao proposed the concept of stickiness of being to rethink solidarity as a tension between attachment and disavowal.14Simbao speaks of this tension in relation to Myriam Dao’s ancestral root that is tied to legacies of French colonialism in Indochina. From queer botanical poetics to a colonial history of botanical art, we have witnessed this similar tension captured in the allure of flowers.

Reflecting on a commonplace understanding of the flower as an organ of self-multiplication, Emanuele Coccia notes: “In the flower, reproduction ceases to be the instrument of individual or specific narcissism to become an ecology of condensation and mixture, because the individual makes the world and the whole world is in labor with the new individual.”15Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture,trans. Dylan J. Montanari(Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), 206. Bringing queerness into a dialogue with this philosophical thought on floral transindividuality, we might add that queer botanical poetics propose a model of kinship and futurity based not only on the notion of reproduction. After all, the poetic and playful invocation of pollination in Gaysorn Prasopkan is not so much about reproduction as about the spread of words that carry queer utopian dreams across time and space.16This utopian vision is discussed in Suntisuk Prabunya’s quotation from a short story titled, “Khwam Faifan ti Raoran” (“Shattered Dream”), published in 1986, in which a dying queer character bids farewell to his “pollen friend,” who soliloquizes the following ending lines: “I am tomorrow’s hope of the Pollens. I have promised with my Pollens who lie scattered on the ground that they will see our flowers flourishing. Sooner or later. . . . And when that day comes, all values of love and goodness will prevail in the history of humankind.” Translation modified from Suntisuk Prabunya’s.

- 1Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 2–3.

- 2Suntisuk Prabunya, “‘His Wounds, My Wounds’: Melancholic Community and Queer Intimate Public in Gaysorn Prasobkarn Magazine” (Council on Thai Studies Annual Meeting, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, November 15, 2020). The original quote is from Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), viii.

- 3For a discussion of orientation, both in the domains of phenomenology and sexuality, see Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

- 4For a recent work on Thai poetry and the cultural history of the Cold War, see Arnika Fuhrmann, Teardrops of Time: Buddhist Aesthetics in the Poetry of Angkarn Kallayanapong (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2020).

- 5Famous lines from the poem read: “A flower has sharp thorns / Not bursting into bloom for an admirer / She blossoms to raise / The glory of the earth.” Translation by Rachel Harrison for Southbank Centre’s Poetry Parnassus festival, 2012, https://www.nationalpoetrylibrary.org.uk/online-poetry/poems/defiance-flower.

- 6Nithikul, Untitled, Gaysorn Prasopkan 1, no. 6 (1985): 56. My translation.

- 7Peter A. Jackson discusses the emergence of commercial Thai male homoerotic magazines in the 1980s such as Mithuna, Mithuna Junior,and Neon in relation to print capitalism and global queer culture in Peter A. Jackson, “Capitalism and Global Queering: National Markets, Parallels Among Sexual Cultures, and Multiple Queer Modernities,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 15, no. 3 (2009): 357–95.

- 8Ann Cvetkovich, “Ephemera,” in Lexicon for an Affective Archive, eds. Giulia Palladini and Marco Pustianaz (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2017), 179–83.

- 9See Eve Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–51.

- 10Rita Felski, “Context Stinks!” New Literary History 42, no. 4 (Autumn 2011): 573–91.

- 11Sorawit Songsataya, “Looking Sideways” (panel discussion, Transversal Orientations, Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) seminar, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 2, 2021).

- 12In her anthropological studies of colonial Indonesia, Ann Laura Stoler has noted the need to shift away from viewing colonial elites as “homogenous communities of common interests” and to rethink the consolidation of colonial authority through notions of intimacy, gender difference, and sexual regulation. See Ann Laura Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 43.

- 13Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (New York: Routledge, 2004).

- 14Simbao speaks of this tension in relation to Myriam Dao’s ancestral root that is tied to legacies of French colonialism in Indochina.

- 15Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture,trans. Dylan J. Montanari(Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), 206.

- 16This utopian vision is discussed in Suntisuk Prabunya’s quotation from a short story titled, “Khwam Faifan ti Raoran” (“Shattered Dream”), published in 1986, in which a dying queer character bids farewell to his “pollen friend,” who soliloquizes the following ending lines: “I am tomorrow’s hope of the Pollens. I have promised with my Pollens who lie scattered on the ground that they will see our flowers flourishing. Sooner or later. . . . And when that day comes, all values of love and goodness will prevail in the history of humankind.” Translation modified from Suntisuk Prabunya’s.