Ming Wong wanders between worlds. From Chinese painting and philosophy to theatre, film, Non-Aligned histories, and the radical politics of queerness, Wong’s artistic worldview comprises a prescient pastiche of cultural possibilities. Emancipated from inflexible ideas of time, place, discipline, or persona, Wong contently choreographs future fandoms.

Wong Binghao: Ming, I see your practice as a continuous intellectual pursuit, and you as an artist-polymath. I am indebted to your continued generosity and candor for this belated epiphany. More than the many signs and surfaces of your work that audiences or critics might pick up on—drag, identity, nation, film, etc.—your artworks and trajectory as an artist feel like manifestations of your ceaseless curiosity about the world. This is a desire that cannot be pinned down. As a chief example, you typically learn and perform new languages (German, Japanese, Turkish, and Italian, among others) and do extensive research on cultural and historical contexts whenever you make a new work. What inspires your fervor for learning and inquiry?

Ming Wong: I have always strongly felt, and still do, like an outsider, the middle child, the outlier, the one who never fits in. I’ve learned that this may be because of a whole intersection of things: being queer; the racial, national “other” (having lived abroad for almost twenty-five years); the artist, the dilettante, the imposter; always in between, forever code-switching. I guess over the years, the strategies I have put to use in my attempts at survival, acceptance, or even some notion of “grace,” have accumulated to form an artistic arsenal that expresses the insistence of my existence, a quest for more equivalence, compassion, and codependency in our lives. I have learned to question systems, partisanships, forms of suspect “solidities”—suspended particles that would settle into sediment were it not for some constant stirring action against profit-driven, patriarchal, racist, colonialist impulses. To queer the system, and even to queer the queer, the only constant is change; contradiction, disloyalty, and betrayal are sometimes inevitable.

WBH: To pick up on the salience of your last point, and departing from the reductive readings of “drag” in your work, how do you think gender and queerness have left imprints on your work? It feels like you mobilize them as modalities of relation in your quest for edification.

MW: One of my late realizations is the awareness of what (or whose) cultural landscape I have been an active participant in, and what (or whose) spheres of influence I would like to be a catalyst for, and that’s a difficult question. I am aware that most of the circles that I operate in are determined by language, along with the correlative legacies of history, culture, philosophy, etc. With globalization’s “lost-in-translations,” one can get caught up in a false consciousness of doing what one thinks is “art,” or of being what one thinks is an “artist.” I try to sieve these ideas of a universal language of art from the workings of market forces.

Personally, I feel as though I have been “dragging” between worlds: a cosmopolitan, diasporic South Chinese identity separate from any notions of nationalism to the People’s Republic of China; still recovering from a vestigial postcolonial hangover (I once heard a drag performer say, “You can take the girl out of Singapore, but you can’t take Singapore out of the girl”); queering the ground of the international (read: Euro-American) art arena that a fool like myself had rushed into and where true art angels fear to tread.1I reference a line from Alexander Pope’s 1711 poem An Essay on Criticism. In these different contexts, I often feel like an unwitting spy, the uninvited guest, disguised in double-drag (or intersectional drag!), a double-crossing, cross-dressing agent. Sometimes I feel like the world isn’t ready for me—is it vain to say that? At times I feel like I’m posing for small change on the sidewalk, biding my time as I wait for the real (Beckettian) circus to arrive.

WBH: Speaking of vanity and its asymmetries, a particular moment that stuck out to me in your performance with Alexander Geist of their electro-pop song “That Girl” was when Geist gestured at you and lip-synched the apropos lyric that you “drap[e] yourself in a cloak of indiscernible stealth.” This made me think of your presentation/performance during a 2011 Hong Kong Art Fair panel debating the notion that “Art Must Be Beautiful,” in which you motioned that “I use beauty a lot in my work, but it [art] cannot stop at beauty. . . . Art has to go beyond surface decoration, distraction, drag, fetishism and commodification.” How do devices of unknowability or mystery show up in your practice, and to what effect?

MW: I think I’ve always been a kind of unwilling performer. That sort of describes my style. Because the expectation of explaining oneself is constantly hoisted upon me by the “mainstream.” As an act of resistance, I try not to be too “authentic” or persuasive or to act in a deliberate manner so as not to be taken too seriously. I think it’s a good thing to keep confusing people. Double-drags and triple agents; what you see is not always what you get; I may speak your language, but my accent throws you off; my references, reactions, and motivations seem like they’re from a different planet. This is not just a matter of black or yellow or brown skins and white masks:2A play on Frantz Fanon’s 1952 Black Skin, White Masks (Peau noire, masques blancs). there’s always another mask, an’ another an’ another an’ another . . . riddles wrapped in mysteries inside enigmas.3I reference Winston Churchill’s 1939 quotation.

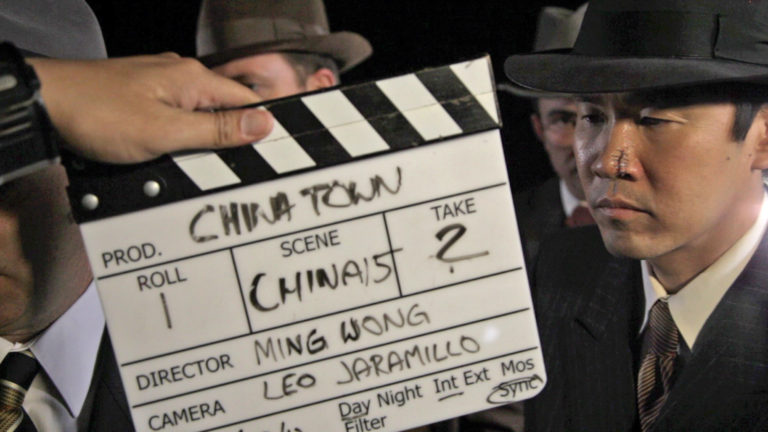

“Chinatown” is one such cipher, synonymous with the unknowable and indecipherable, a legacy of twentieth-century cultural stereotypes in the English-speaking world. Ten years ago when I was in Los Angeles to do research for a new commission for REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater), I ended up dragging as Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, John Huston, and the shady sister-daughter in Making Chinatown (2012), my own hyper-incestuous Chinese knockoff of the eponymous Polanski film—infusing scenes from the dusty cinematic classic with a breath of fresh Chinatown-ness. A few months later, I went back to make a sequel called After Chinatown (2012), in which I trace the cinematic journeys of pioneering migrants who sailed across the Pacific, from Hong Kong to Hollywood. In the video, a Chinese detective dons a “Chinaman” mask while on the run around Chinatowns in Los Angeles and San Francisco, which are cinematic stand-ins for the hybrid city of Hong Kong. Stalking the detective is a film “chinoir”–style femme fatale—an Asian Barbara Stanwyck (out of Double Indemnity) in blonde wig and sunglasses, dragging as Brigitte Lin in disguise in Chungking Express. They play two imposters looking for lost loves and lost relations, running away from big troubles in little Chinas.4A play on the 1986 film Big Trouble in Little China.

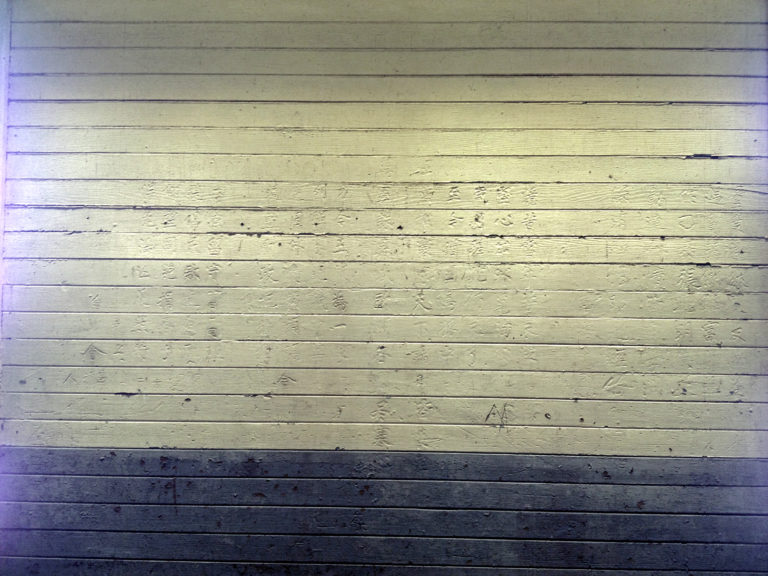

While researching in San Francisco, I stumbled onto Angel Island, which neighbors Alcatraz and is where Chinese immigrants to the United States were “quarantined” and interrogated for weeks, months, or years as a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Over two hundred poems, written in Chinese, of hope, despair, and persecution are carved into the walls of the detention barracks. Noticed by a park ranger right before the demolition of these buildings in the 1970s, these poems emerged like secret messages from the past, alerting activists to save these walls that could talk. Today one could imagine those forefathers saying, “I can’t believe we’re still protesting this shit!” Since over a year ago, the spate of racist attacks against Asians who have been scapegoated for the COVID-19 pandemic inevitably still invokes the era of yellow peril that manifested itself in late colonial Europe and America at the turn of the twentieth century.

During my hibernation from the pandemic, I studied and listened to Hong Kong Cantonese opera and started playing the piano again. Now I’m composing music with a friend of mine who is a classical music conductor; we’re working on a piece called “Rhapsody in Yellow”—a re-mapping of the “sonic regimes” of the United States and China via an assimilation of their national musical monuments Rhapsody in Blue and the Yellow River Concerto. Next year marks the fiftieth anniversary of Nixon’s historic visit to China. It’s distressing to see how far apart the two nations have become from each other.

WBH: This is a good point to discuss your work in MoMA’s collection: Windows On The World, Part 2 (2014), a twenty-four-channel video installation that explores the relationship between sci-fi and twentieth-century Cantonese opera. How do you see this work responding to the media landscape of China at that particular moment in time?

MW: I spent extensive periods of time in Hong Kong from 2010 onward, researching the technological transformation of the traditional theater of Chinese opera via the emergence of Cantonese opera movies of the 1930s and ’40s. Opera troupes sailed from Hong Kong to perform for the largely Southern Chinese immigrant communities in Chinatowns on the West coast of the United States. Between Hong Kong and Hollywood, there emerged a lively, highly adaptive, genre-busting hybrid cinematic artform that ingeniously fused East and West, past and present. It made me wonder if those artistic innovations of early Cantonese opera cinema could be directed to reflect on the tumultuous events of the twentieth century and toward the future.

It was during those years that I, with the eyes of an artist, witnessed the unfolding changes in Hong Kong and Southern China, the lands of my ancestors, with interest. There was the arrival of Art Basel in Hong Kong and mega-galleries on its shores, the setting up of the M+ museum of visual culture, and the ever-increasing circles of influence from the mainland Chinese art scene. Set against these developments was the mood of growing unrest from a disgruntled post-handover population, which culminated in the protests of the Umbrella Movement, bringing this shiny Sino-futuristic city to a standstill by defiant youth occupying the streets.

Speculative fiction or science fiction (SF) has always been a platform for reimagining one’s realities and futures, and the study of the history of SF in China has revealed moments throughout the twentieth century when different futures were dreamed of: technological advancement, decolonial liberation, political utopias, or dystopian hyperrealities. Through a montage of the history of Chinese SF with Asian mythology and SF cinema, news footage of China’s space program, and elements of Cantonese opera, I attempted to open windows into the metaphysical contradictions and cultural clashes of my own lived, queer existence.

WBH: In 2019, you joined the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden, as professor of performance in the expanded field. How has this new city/job influenced your artistic practice? Do you feel like you have (or will ever) settle in one place? I ask this because so much of your work seems to narrativize your adaptations to different contexts.

MW: I started this position just before the pandemic, and it has been a challenge in the last year and a half to get beyond the restrictions and social distancing to explore meanings of performance beyond Zoom cages! Going on historical guided walks in the city has helped me to familiarize myself with my new surroundings and also served as a pedagogical foundation for collective performance projects.

Also, I’ve formed a Swedish K-pop boy band, inspired by the cultural phenomenon that is BTS, and also by the fact that a lot of K-pop is crafted by Swedish songwriters and music producers. Our hope is that by “dragging” K-pop from Sweden to Korea and back to Sweden again, perhaps we can discover something about Swedish identity. The band will have its digital debut at the Seoul Mediacity Biennial later this year.

Since my regular research trips to Asia have been interrupted by the coronavirus, I have succumbed to a feeling of emotional exile, as when I look on from a distance at the recent turn of events in Hong Kong or in parts of Southeast Asia. Perhaps this period of social distance from my cultural wellspring will translate into a deeper acknowledgment of and insight about what I have learned and experienced in my transformative artistic positions and journeys across borders through the past decade.

I’m not sure this feeling of restlessness will ever end. At the moment I remain wary of how tensions between China and the rest of the world are played out in the media and quickly trickle down to reductive assumptions of race, regardless of other forms of identity. This feels like the beginning of another vicious cycle. I can’t help but feel that I have to put my queer foot down on it.

- 1I reference a line from Alexander Pope’s 1711 poem An Essay on Criticism.

- 2A play on Frantz Fanon’s 1952 Black Skin, White Masks (Peau noire, masques blancs).

- 3I reference Winston Churchill’s 1939 quotation.

- 4A play on the 1986 film Big Trouble in Little China.