Through a close reading of Kowkülen (Liquid Being) (2020), a video piece by artist Sebastián Calfuqueo, the author delves into the work’s intricate engagement of Mapuche cosmopolitics, proposing a critical approach to the neoliberal violence of water commodification in Chile vis-à-vis nonbinary modes of inhabiting the world.

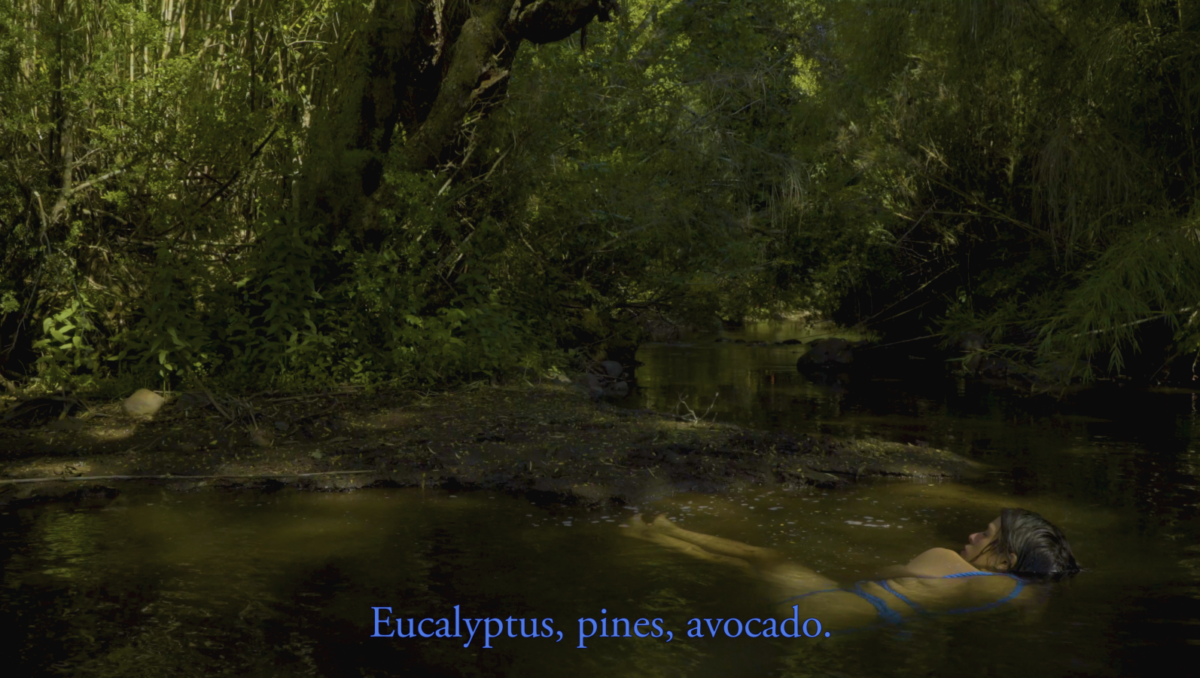

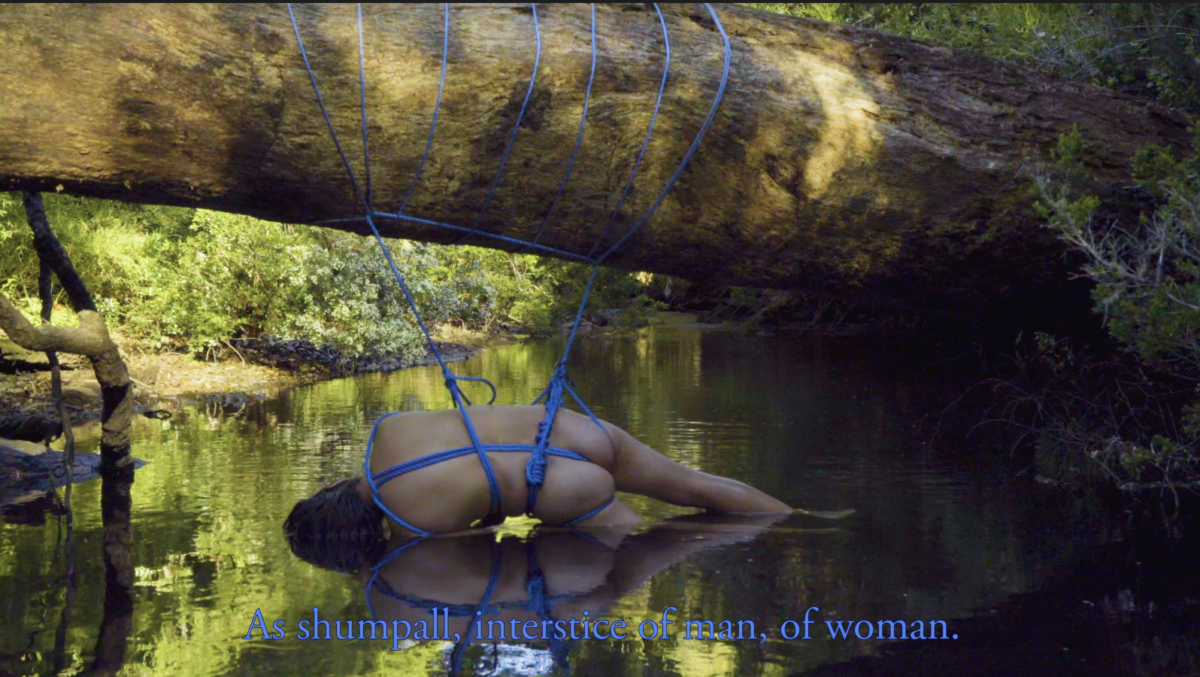

At the center of the frame, in the cold waters of the Cautín, the river that rises on the western slopes of the Cordillera de Las Raíces and flows in La Araucanía Region in south-central Chile, lies the naked body of nonbinary Mapuche artist Sebastián Calfuqueo (born 1991). Surrounded by oak, laurel, and cinnamon trees, Calfuqueo is shown on their side, half under water, their back to the camera. Bound with a blue rope, the sunlight touches the artist’s flesh, drawing organic shapes projected through the branches above. This scene is from a three-minute video-performance made by Calfuqueo in 2020, a work titled Kowkülen, meaning “Liquid Being” in Mapudungun, the language spoken by the Mapuche.1A version of this text was delivered in February 2021 at the panel “Down to Earth: Womxn Artists and Ecological Practices in Latin America,” chaired by Madeline Murphy Turner at the 109th College Art Association (CAA) Annual Conference.

In the English version of the work,2This video exists in both English and Spanish versions. Kowkülen begins with a statement by the artist that, lettered in blue over a black background, reads: “In Chile the 1981 Water Code written during Pinochet’s dictatorship is still ruling. Such document defines water in Chile as a marketable good.” The text then merges into blackness, while we hear the river descending over stones. The sound of running water continues throughout the video, with Calfuqueo never uttering a word. Instead, they allow the river to speak. As Daniela Catrileo, Mapuche poet and member with Calfuqueo of the feminist Colectivo Mapuche Rangiñtulewfü, writes in her poetry book Río Herido: “El río es voz / que no / calla /¿Qué se abre / en el lenguaje de / las aguas?”3“The river is a voice / that does not fall silent / What opens / in the language of / the waters?” Daniela Catrileo, Río Herido (Santiago: Edicola, 2016), 19. Translation by Paula Solimano.

In the second section of the video, we see the artist once again in the previously described scene, this time with the text: “The history of the peoples / Settled historically / Inaltu lafken mew / Next to the water / I have been here / In a liquid state / Running through different basins. Ngen ko, Arüm ko, Ngürü fily, Kay kay, / Witnesses of this journey.” Merging Mapudungun with vernacular languages such as English or Spanish to create a poetic-like manifesto that continues throughout the work, Calfuqueo’s aim in Kowkülen is twofold: On the one hand, the artist seeks to criticize water commodification in neoliberal Chile vis-à-vis the binary model of coloniality. On the other, they offer a powerful visuality that embraces alternative ways of inhabiting the world from the perspective of the Mapuche.

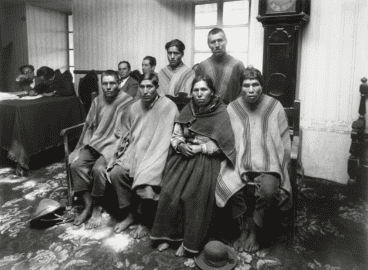

In order to elaborate on this point, a brief history of Mapuche colonization in Chile is necessary. Maintaining control of their lands during the Spanish colonial rule, the Mapuche were colonized in the late nineteenth century by the new state of Chile. Through a process infamously called the “Pacification of the Araucanía,” the Mapuche were humiliated and devastated, left with small and isolated pieces of land literally called reducciones (reductions). In an effort to whiten the nation, much of their ancestral lands were sold by the Chilean state to Chilean and European settlers to establish fundos, or large farms.4For more on this, see Patricia Richard, Race and the Chilean Miracle: Neoliberalism, Democracy, and Indigenous Rights (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013). Within this context of internal coloniality,5For more on this, see Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. General Augusto Pinochet’s bloody dictatorship (1973–90) inaugurated a second and even more durable regime: a harsh form of neoliberalism. Upon the return to democracy, the center-left government, aiming to repair centuries of land occupation and discrimination toward the Mapuche, created the Ley Indígena Nº 19.253 (Indigenous Law) in 1993 and provided state funding for the Mapuche to buy available land. Importantly, however, the land that was offered to the Mapuche was not necessarily sacred, meaning that the State disregarded a central aspect of Mapuche cosmovision. Today, in the context of the anti-terrorist law passed under the socialist administration of Ricardo Lagos, which criminalizes many Mapuche,6For more on this, see Human Rights Watch, Undue Process: Terrorism Trials, Military Courts and the Mapuche in Southern Chile, October 27, 2004, B1605, https://www.refworld.org/docid/42c3bcf00.html those who resist the nation’s market-oriented ends by defending their lands and right to water have been systematically shot, imprisoned, and killed. “Ni socialista ni capitalista / sino todo lo contrario. Economía Mapuche de Subsistencia,” said the late poet Nicanor Parra (1914–2018) supporting the Mapuche resistance movement against neoliberalism and arguing for an independent Mapuche economy of subsistence.7“Neither socialist nor capitalist / but quite the opposite. Mapuche Economy of Subsistence.” “Eschucha el discurso de Nicanor Parra cuando recibió el grado de Docto Honoris Cuasa de la UdeC,” 1996, https://www.soychile.cl/Concepcion/Cultura/2018/01/23/512768/Escucha-el-discurso-de-Nicanor-Parra-cuando-recibio-el-grado-de-Doctor-Honoris-Causa-de-la-Universidad-de-Concepcion.aspx. Translation by author. Politically persecuted, economically exploited, and racially oppressed, the Mapuche, while in the new so-called democratic context were able to speak through their insertion into the logic of the market, their cosmopolitics was certainly not being heard.8Richard, Race and the Chilean Miracle, 8. As critical race theorists Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang write, “Solidarity is an uneasy and unsettled matter.”9Tuck and K. Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” 3.

In Mapuche cosmopolitics, the systematic loss of land must be seen not only through an economic lens, but also as a historical and ontological issue.10Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, “El tiempo del trueno guerrero mapuche: lo silvestre, el estado chileno salvaje y las machi civilizadas,” Mitológicas 30 (2015), 15. In a recent collaboration with Mapuche healer machi Francisca Kolipi, anthropologist Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, for instance, explains that in the top of the Millali hill in Cautín, very close to the river in which Calfuqueo created Kowkülen, the living and the dead, as well as the past, present, and future coexist.11See ibid., 9–60. See also Tom D. Dillehay, Monuments, Empires, and Resistance: The Araucanian Polity and Ritual Narratives (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007). Because of its sacred features, this place is used by machis such as Francisca to perform ceremonies and rituals, and to gain the power and knowledge to conduct spiritual warfare against the community’s enemies, such as settlers and forestry and hydroelectric companies.12Bacigalupo, “El tiempo del trueno guerrero mapuche: lo silvestre, el estado chileno salvaje y las machi civilizadas,” 9–60. This means that in Mapuche cosmovision, nature is not separated from history, spirituality, and politics. In other words, nature is not related to science or to economic progress as conceived in the binary model of modernity.

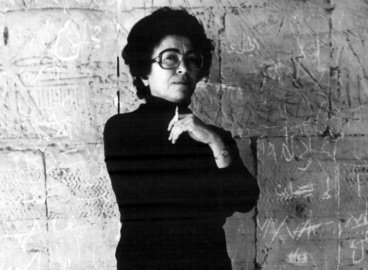

Born in Santiago’s working-class commune of Lo Prado in 1991, Calfuqueo learned about Mapuche cosmovision through their grandmother, Isolina Huechucura Manquecura. Isolina had migrated to the capital in the mid-twentieth century amid massive Mapuche mobilization, escaping systematic discrimination and abuse in Wallmapu, the ancestral territory of the Mapuche people in present-day south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina. While attending Liceo Manuel Barros Borgoño, a renowned all-boys public secondary school in Chile whose curriculum follows western epistemic canons, the artist was bullied by their classmates because of their appearance, gender identification, and surname, Calfuqueo, which betrays the artist’s indigenous roots. Importantly, “Calfu” means blue in Mapudungun—and blue, according to Mapuche poet Elicura Chihuailaf, means all that is sacred: the mountains, the lakes, the rivers, the sound.13“Kalfu Mapu: El azúl de Elicura Chihuailaf en territorio ancestral,” Territorio Ancestral website, July 3, 2017, https://www.territorioancestral.cl/2017/07/03/kalfu-mapu-el-azul-de-elicura-chihuailaf-en-territorio-ancestral/ Thus the presence of this color in Kowkülen, through the rope, in the subtitles, and in the text.

In the next scene in Kowkülen, the artist’s body is still half underwater, their head almost touching the river’s edge. We read: “Water is territory / Neoliberal extractivism / The market over life, . . .” As Calfuqueo’s body moves slowly downriver, and before it disappears from the frame, we read: “20 liters, 20 liters, 20 liters, of water daily. / Eucalyptus, pines, avocado. / Mapu kishu angkükelay, kakelu angkümmapukey.” This last sentence, in Mapudungun, is not translated, inviting the non-Mapudungun speaker/viewer to another way of understanding through sound, activating new relationships between sonic senses and meaning. As Mapuche scholar Luis E. Cárcamo-Huechante explains, “Mapu” can signify “land,” “territory,” “space,” “environment,” or “universe,” and “zungun”also contains various meanings: “tongue,” “language,” “voice,” “sound,” and “sense.”14See Luis E. Cárcamo-Huechante, “No + Wingka Word: Sounds of Mapuche Resurgence in the Poetry of Leonel Lienlaf,” Radical History Review 124 (2016): 102–16. Mapudungun therefore “detaches from an anthropocentric logic and expresses a linguistic territory of multiple resonances: the phonetics of a world populated by beings that whisper, mumble, talk, scream, or moo.”15Ibid., 103. In keeping the sound, the senses of zungu through their writing, Calfuqueo’s work resists linguistic translation as the only source of understanding, insisting on a world—that of the Mapuche—that persists despite neoliberal extractivism. It puts forward a mode of inhabiting otherwise, that is, a mode of living and existing in Wallmapu and its diasporic communities by resisting modernity’s binominal relationships between signifier and signified and original and translation.

Calufuqeo’s challenges to the binaries invented by Western colonial modernity are present throughout the work. For instance, time, in Mapuche cosmovision, is understood from a nonlinear, nonprogressive perspective that rejects modernity’s binominal idea in which events and memories exist only before or after other events and memories. Literally submerging themselves halfway into the river, Calfuqueo writes: “I have been here / In a liquid state . . .” Using the present perfect, the artist highlights that they are “here,” inhabiting a nonlinear ecology that resists the progressive policies of “solidarity,” as elaborated by Tuck and Yang, of a nation-state that systematically destroys biodiversity and Mapuche life through monocultural and hydroelectric projects.

Writing about this and other related works, Mapuche cultural theorist Cristian Vargas Paillahueque reflects on the issue of gender, noting that Calfuqueo’s work reveals that the Mapuche struggle for water invites other memories and beliefs that have been excised from the hegemonic imaginary.16Cristian Vargas Paillahueque, “Ko konümpakey tañi weychan (el agua rememora sus luchas). Sobre ko ñi weychan, de Sebastián Calfuqueo,” Artishock: Revista de Arte Contemporáneo, November 28, 2020, https://artishockrevista.com/2020/11/28/ko-ni-weychan-sebastian-calfuqueo/. As Calfuqueo writes in Kowkülen, as the blue rope ties their body to the trunk of a native tree: “I want to be a fish / Without a sex to be reckoned with / As shumpall, interstice of man, of woman / Non-binary waters.” The naked body of the artist in connection to native trees, water, and certainly the color blue thus aims to recover a nonbinary Mapuche identity that was central to Mapuche cosmovision and beliefs before the Chilean colonization, showing a nonbinary (and non-binominal) way of inhabiting in which nature, gender, memories, time, and language, all intersect in a liquid, fluid condition. They overlap to formulate a critique against the neoliberal and colonial state, creating, in turn, other forms of representation that are radically reshaping debates on art, race, territory, language, and gender in Chile in the age of neoliberalism. As Calfuqueo writes by the end of the video: “To know that I am part of the territory. / Ad mongen, Itrofil mongen.” And as the artist concludes, in all capital letters: “WATER IS NOT FOR SALE.”

- 1A version of this text was delivered in February 2021 at the panel “Down to Earth: Womxn Artists and Ecological Practices in Latin America,” chaired by Madeline Murphy Turner at the 109th College Art Association (CAA) Annual Conference.

- 2This video exists in both English and Spanish versions.

- 3“The river is a voice / that does not fall silent / What opens / in the language of / the waters?” Daniela Catrileo, Río Herido (Santiago: Edicola, 2016), 19. Translation by Paula Solimano.

- 4For more on this, see Patricia Richard, Race and the Chilean Miracle: Neoliberalism, Democracy, and Indigenous Rights (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013).

- 5For more on this, see Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

- 6For more on this, see Human Rights Watch, Undue Process: Terrorism Trials, Military Courts and the Mapuche in Southern Chile, October 27, 2004, B1605, https://www.refworld.org/docid/42c3bcf00.html

- 7“Neither socialist nor capitalist / but quite the opposite. Mapuche Economy of Subsistence.” “Eschucha el discurso de Nicanor Parra cuando recibió el grado de Docto Honoris Cuasa de la UdeC,” 1996, https://www.soychile.cl/Concepcion/Cultura/2018/01/23/512768/Escucha-el-discurso-de-Nicanor-Parra-cuando-recibio-el-grado-de-Doctor-Honoris-Causa-de-la-Universidad-de-Concepcion.aspx. Translation by author.

- 8Richard, Race and the Chilean Miracle, 8.

- 9Tuck and K. Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” 3.

- 10Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, “El tiempo del trueno guerrero mapuche: lo silvestre, el estado chileno salvaje y las machi civilizadas,” Mitológicas 30 (2015), 15.

- 11See ibid., 9–60. See also Tom D. Dillehay, Monuments, Empires, and Resistance: The Araucanian Polity and Ritual Narratives (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- 12Bacigalupo, “El tiempo del trueno guerrero mapuche: lo silvestre, el estado chileno salvaje y las machi civilizadas,” 9–60.

- 13“Kalfu Mapu: El azúl de Elicura Chihuailaf en territorio ancestral,” Territorio Ancestral website, July 3, 2017, https://www.territorioancestral.cl/2017/07/03/kalfu-mapu-el-azul-de-elicura-chihuailaf-en-territorio-ancestral/

- 14See Luis E. Cárcamo-Huechante, “No + Wingka Word: Sounds of Mapuche Resurgence in the Poetry of Leonel Lienlaf,” Radical History Review 124 (2016): 102–16.

- 15Ibid., 103.

- 16Cristian Vargas Paillahueque, “Ko konümpakey tañi weychan (el agua rememora sus luchas). Sobre ko ñi weychan, de Sebastián Calfuqueo,” Artishock: Revista de Arte Contemporáneo, November 28, 2020, https://artishockrevista.com/2020/11/28/ko-ni-weychan-sebastian-calfuqueo/.