The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was established in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, in 1961, during the peak of the Cold War, drawing inspiration from the principles of the 1955 Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. Founded by developing countries opposed to formal alignment with either the United States or the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, NAM advocated for national self-determination and resistance against all forms of colonialism and imperialism. Its united front on social and economic policies proved only the beginning, as it also sought to create a united artistic front, an aim resulting in the opening of the Gallery of Art of the Non-Aligned Countries “Josip Broz Tito” on September 1, 1984, in Titograd (today Podgorica), Yugoslavia.

Although Yugoslav artists exhibited works at the Alexandria Biennale (Egypt), São Paulo Biennial (Brazil), and New Delhi Triennale (India), and artists from NAM member countries exhibited at the International Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana (Yugoslavia), the Gallery “Josip Broz Tito” was the only art institution established under NAM auspices1Bojana Piškur, “Southern Constellations: Other Histories, Other Modernities,” in Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2019), 18., a fact crucial to grasping the significance of its collection2Radina Vučetić, “The Exhibition: Exhibitions as Spaces of Cultural Encounter—Yugoslavia and Africa,” in Socialist Internationalism and the Gritty Politics of the Particular: Second-Third World Spaces in the Cold War, ed. Kristin Roth-Ey (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), 93..

The archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro3The archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro (MCAM), were established with MCAM in 2023. MCAM was founded through the integration of the former Contemporary Art Centre of Montenegro, which itself has included the collection of the Gallery “Josip Broz Tito” since the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1995., which was founded through the integration of the Gallery “Josip Broz Tito” and the Republic Cultural Centre after the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1995, reveal a transnational network of cultural diplomacy linking fifty-six non-aligned countries to generate a collection of about eight hundred artworks originating from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe. Though criticized by Yugoslav art historians for collecting “works from faraway exotic places” and “from authoritarian states that support official art,”4Bojana Piškur and Đorđe Balmazović, “Non-Aligned Cross-Cultural Pollination: A Short Graphic Novel,” in Socialist Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement: Social, Cultural, Political, and Economic Imaginaries, ed. Paul Stubbs (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023), 164. the Gallery challenged what its founders viewed as the imperial model that prevailed in many museums in that it acquired its holdings solely through gifts and donations. This essay discusses the transnational model of assembling an art collection by employing NAM networks, countering the imperial model of doing so through colonial violence, looting, or transactional exchange.

Situated in a nineteenth-century castle built by Nicholas I, the last king of Montenegro, and surrounded by a large park complex, the Gallery began collecting, preserving, and exhibiting the art of non-aligned and developing countries in 1984. This effort made Yugoslavia a cultural center, one that attracted artistic productions from North Korea, India, Egypt, Angola, and Cuba, among many other NAM countries (fig. 1).

A European nation situated between the Eastern and Western blocs and in proximity to the African and Asian Mediterranean shores, Yugoslavia proved to be a perfect site for an art space dedicated to the exhibition of the artistic production of NAM countries. Although the rupture with the Soviet Union in 1948 undeniably served as the primary catalyst for a significant transformation in its foreign policy, the Yugoslav Partisans’ resistance against fascism bore symbolic resonance with anti-colonial struggles in the Global South6The Yugoslav Partisans were members of the resistance force led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia against the Axis powers, primarily Nazi Germany, in occupied Yugoslavia during World War II.. Not only did the Partisans unite the diverse nationalities within Yugoslavia against local fascist regimes, they also accomplished a remarkable feat in making it the only occupied European nation to liberate itself from Axis occupation7Paul Stubbs, introduction to Socialist Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement, 11.. In so doing, they established Yugoslavia’s distinct position beyond the spheres of influence of the United States and the Soviet Union. Operating in a state of “semiperipherality,” Yugoslavia fostered the emergence of distinct perspectives and, notably, “ambivalence . . . regarding . . . Western modernity”8Marina Blagojević, Knowledge Production at the Semiperiphery: A Gender Perspective (Belgrade: Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, 2009), 33. and hostility toward colonial subjectivity. As sociologist Marina Blagojević contends, “Semiperipherality” is “essentially shaped by the effort to catch up with the core, on [the] one hand, and [on the other] to resist the integration into the core, so as not to lose its cultural characteristics,” an ethos that made Yugoslavia a suitable site for the NAM collection.9Blagojević, Knowledge Production at the Semiperiphery, 33–34.

The Gallery’s model of collecting and exhibiting artworks helped establish its specific identity as an institution that steered clear of cultural colonialism. In an introduction to an undated Gallery exhibition catalogue, Raif Dizdarević, Yugoslav Federal Secretary of Foreign Affairs, remarks how the institution collected art, “preserving national identity despite colonialism, occupation, foreign domination, despite racism, economic exploitation, removal of cultural treasures,” and all other forms of forced exploitation.10Raif Dizdarević, Galerija umjetnosti nesvrstanih zemalja “Josip Broz Tito”—Titograd—Yugoslavia, exh.cat. (Titograd: Gallery of Art of the Non-Aligned Countries “Josip Broz Tito,” n.d.), 2. In the 1970s, a comparable anti-imperialist model united transnational art projects such as the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (Museum of Solidarity) in Santiago, Chile, and the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in Beirut, Lebanon.11In 1972, the Solidarity Museum mounted its first exhibit, which was held at the Santiago Museum of Contemporary Art in Chile. Featuring works donated by international artists, the Solidarity Museum was founded under Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government, the world’s first democratically elected socialist administration. In 1978, inspired by the Solidarity Museum, the International Art Exhibition for Palestine took the form of a traveling exhibition that was meant to tour until it could return to historic Palestine. Organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization, the exhibition comprised almost 200 works donated by 200 artists from nearly 30 countries. These endeavors fostered transnational solidarity movements and strengthened alliances among countries in the Global South, the same vision NAM pursued through the establishment of the Gallery in Yugoslavia.12The assertion that the Gallery was not established by NAM is a matter of debate, with historical sources offering varying accounts, some of which suggest alternative origins or founders. As Radina Vučetić explains in her essay, “Although the Art Gallery of the Non-Aligned Countries was a Yugoslav-based institution, it was more than a Yugoslav project. At the Seventh Non-Aligned Conference in New Delhi in 1983, non-aligned countries were invited to collaborate in the creation of the Non-Aligned Gallery for the promotion of non-aligned art. The First Conferences of Ministers of Culture of the Non-Aligned and Developing Countries in Pyongyang (1983) and Luanda (1985) further elaborated the activities of the gallery. After a number of meetings of the non-aligned leaders, a decision was taken in New Delhi in 1986 that the ‘Josip Broz Tito’ Art Gallery of the Non-Aligned Countries should become a joint non-aligned institution” (Radina Vučetić, “The Exhibition: Exhibitions as Spaces of Cultural Encounter—Yugoslavia and Africa,” in Socialist Internationalism and the Gritty Politics of the Particular: Second-Third World Spaces in the Cold War, ed. Kristin Roth-Ey (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), 93–94). Vučetić’s analysis, based on evidence from official NAM Summit records, highlights the significant role NAM played in the development of the Gallery. For a more thorough examination of these sources and the contested nature of this information, consult the documents from the NAM Summits. The full archive of NAM Summit records is accessible on the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies website, managed by the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey: http://cns.miis.edu/nam/index.php/meeting/index?Meeting%5Bforum_id%5D=5&name=NAM+Summits

The works in the Gallery’s collection, with the exception of objects made by artists in residence in Titograd, were processed and administrated by Yugoslav embassies based in NAM countries before being sent to Yugoslavia and exhibited. Indeed, letters exchanged between non-aligned countries, Yugoslav embassies, and Gallery personnel show that the acquisition process followed a structured pattern: countries would submit lists of artworks they wished to donate, and then the Gallery would systematically incorporate them into the collection. Although the acquisition process varied across the fifty-six countries donating works, it chiefly relied upon art institutions, cultural organizations, and appointed artists acting as liaisons between NAM countries and the Gallery. Notably, no records indicate the rejection of any submitted works, a practice that resulted in not only a heterogeneous collection but also eclectic exhibitions.

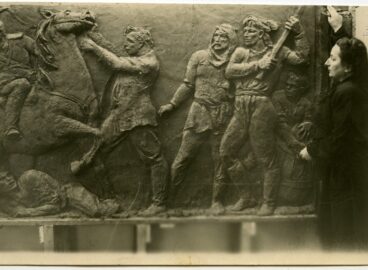

In the absence of presentation directives, Gallery curators chose to display acquired objects alongside each other, highlighting the collaborative and transnational dynamics inherent in NAM networks. This inclusive approach to collecting and exhibiting is also reflected in the Gallery’s array of objects, which encompasses various time periods and mediums. For example, a photograph of a display of works in the permanent collection captures its wide-ranging nature and scope (fig. 2): two antique Cypriot vessels, one from about the 14th century and the other from 725–600 BCE, shown together in a glass cabinet; a sequence of Indian modernist paintings by, left to right, Brahm Prakash, Rameshwar Broota (born 1941), and Gurcharan Singh (born 1949) on the walls; and a white marble sculpture by Indian artist Awtar Singh (1929–2002) on the floor.

The Gallery’s permanent collection ranges from archaeological objects from as far back as the seventh century BCE to contemporary works from across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Europe. Although the collection includes works in a range of mediums and from different time periods, modern and contemporary artworks dominate its holdings. Between 1988 and 1990, for example, the Gallery organized more than one hundred exhibitions featuring art from different countries, regions, and eras.13Milan Marović, “Galerija umjetnosti nesvrstanih zemalja “Josip Broz Tito” Titograd,” Informatica museologica 2, nos. 3–4 (October 1990): 47. While it primarily sought to collect and present works from non-aligned countries, it also organized permanent exhibitions, special exhibitions in Yugoslavia and abroad, lectures and conferences, on-site artistic interventions, and publications promoting the artistic production of NAM countries. By activating the space through a range of public-facing activities, the Gallery swiftly became the hub of NAM’s artistic networks as it drew people from all over the world to Yugoslavia.

By examining three types of collecting by the Gallery—works created on-site, works produced in other non-aligned countries, and works made off-site with NAM’s mission in mind—this essay will reveal how the Gallery expanded NAM’s transnational solidarity networks and challenged the imperial model of collecting by assembling a collection solely through gifts and donations.

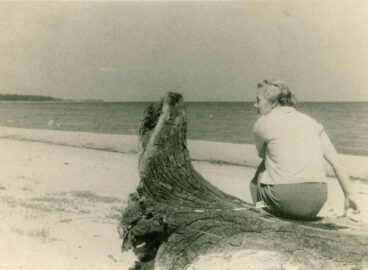

Many artists from NAM countries participated in Gallery residencies, creating art on-site and giving lectures about the art of their respective nations, activities that fostered opportunities to network internationally. A white marble sculpture by Zimbabwean sculptor Bernard Matemera (1946–2002) is an excellent example of a work created by an artist in residence. Porodica (Family, 1987) remains central to the collection as it has been greeting Gallery visitors since its unveiling in 1987 (fig. 3).14Bernard Matemera. Porodica (Family). 1987. White marble, 98 7/16 x 64 3/16 x 62 5/8 in. (250 x 163 x 159 cm). Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro. By 1987, Zimbabwe (which gained independence in 1980, making it one of the last African countries to do so) sought to assert its cultural identity and promote its national narrative on the international stage.15Jesmael Mataga, “Local Communities, Counter-Heritage, and Heritage Diversity: Experiences from Zimbabwe,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Heritage and Politics, ed. Gönül Bozoğlu et al. (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2024), 121. Therefore, the Gallery’s invitation to a Zimbabwean artist to undertake a residency and the inclusion of his work in the permanent collection symbolizes more than Zimbabwe’s integration into the global anti-colonial discourse. To be sure, it also reaffirms the Gallery’s dedication to supporting artists and exhibiting art from nations actively engaged in decolonization and self-determination.

The Gallery’s collection also includes two sculptures Matemera made on-site using locally sourced stone. In his works, Matemera explores African folklore, myths, and legends, a pursuit that has made his sculptures of interest beyond Africa.16Christine Scherer, “Working on the Small Difference: Notes on the Making of Sculpture in Tengenenge, Zimbabwe,” in African Art and Agency in the Workshop, ed. Sidney Littlefield Kasfir and Till Förster (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 194. One monumental piece exhibited on the Gallery’s front lawn embodies themes and styles Matemera examined across his oeuvre as he carved African histories and myths into his works (fig. 4).

The captivating painting by Egyptian artist and activist Inji Efflatoun (1924–1989) is notable as a piece created in a non-aligned country and later gifted to the Gallery. Seljanka i banane (Peasant Woman and Bananas, 1968) depicts a working-class woman seated in a banana tree plantation, themes Efflatoun explored from the mid-1960s onward (fig. 5).17Myrna Ayad, “Overlooked No More: Inji Efflatoun, Egyptian Artist of the People,” New York Times, April 29, 2021, updated May 3, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/29/obituaries/inji-efflatoun-overlooked.html. Efflatoun, alongside other Egyptian artists represented in the collection, such as Rabab Nemr (born 1939), Hussein El Gebaly (1934–2014), and Zeinab Abdel Hamid (1919–2002), made works “that expressed the characters of the Egyptian people and recorded the urban and rural landscapes of the country,” a theme explored across the Gallery’s Egyptian holdings.18Sabrina DeTurk, Street Art in the Middle East (London: I. B. Tauris, 2019), 40. This particular collection of works comprises eighty-two objects, a large number of which were made by women. Due to the lack of records regarding the selection process, one wonders whether these objects were given because works by women were deemed minor or if the Egyptian regime was intentionally aiming to highlight the artistic contributions of women through the Gallery’s transnational solidarity networks.

A founding NAM member state, Egypt donated the most works to the collection of any nation, solidifying its continuous support of the project and showcasing the steadfast leadership of its fourth president, Hosni Mubarak, who advocated for deeper South-South cooperation at the 7th Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of NAM held in 1983 in New Delhi.19Yasmin Qureshi, “The Seventh Summit of Non-Aligned Nations,” Pakistan Horizon 36, no. 2 (Second Quarter, 1983): 54. In the 7th Summit’s final declaration, under the section “Education and Culture,” it is “recommended that the non-aligned countries should actively collaborate in enriching the content and enlarging the scope of the Gallery of Arts of all non-aligned countries, established by the City Assembly of Titograd, Yugoslavia, and invited the coordinating countries to consider concrete measures in this regard.”20Non-Aligned Movement, “Declaration of the 7th Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Movement” (New Delhi, March 7–12, 1983), 133, http://cns.miis.edu/nam/documents/Official_Document/7th_Summit_FD_New_Delhi_Declaration_1983_Whole.pdf After receiving an official invitation to collaborate in the formation of the Gallery “Josip Broz Tito,” Egypt donated works reminiscent of Efflatoun’s oeuvre, emphasizing the human subject and everyday life, two themes central to NAM, and the collective struggle for equality and peace amid the Cold War.

A work in the collection made off-site by Cypriot artist Hambis Tsangaris (born 1947), founder of the Hambis School of Printmaking, celebrates International Children’s Day and, at the same time, extends NAM’s philosophy of non-alignment, intercommunal peace, and coexistence. Cyprus, a Mediterranean island country and founding member of NAM, played a critical role as a nation that has historically followed a non-aligned foreign policy. For instance, Greek Cypriot authorities saw NAM as a potential source of further international backing for constitutional reforms aimed at mitigating the inter-communal strife between the principal ethnic groups—Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots—an issue central to Tsangaris’s practice.21Evanthis Hatzivassiliou, “Cyprus at the Crossroads, 1959–63,” European History Quarterly 35, no. 4 (October 1, 2005): 536–37, https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691405056875. In Greek and Turkish, the official languages of the Republic of Cyprus, as well as in English, Tsangaris advocates “PEACE IN THE HOMELAND / PEACE IN THE WORLD,” addressing both the intercommunal conflicts between Greek and Turkish Cypriots and the broader geopolitical strains stemming from the Cold War (fig. 6).

In Prvi jun—Međunardni dan djeteta (June 1—International Children’s Day, 1977), Tsangaris captures the essence of folk culture, myth, and tradition by integrating abstracted representations of nature and figures—such as the sun, sea, human figures, birds, and fish—symbolizing connections that unify the island. Tsangaris’s work not only raises questions about the island’s geopolitical reality of being situated between the east-west axis, it also deepens the complexity of solidarity networks within NAM, which in turn lends further significance to the Gallery as a space capable of collecting “art of the world” through gifts and donations.22Bojana Piškur, “Southern Constellations: Other Histories, Other Modernities,” in Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned, exh. cat. (Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, 2019), 19.

Many western museums, thanks to acquisition practices now looked upon as unethical, contain highly diverse collections, especially given their colonial legacies. At the same moment the Gallery opened in 1984, many such institutions flaunted their eclecticism, as did MoMA in its 1984–85 exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art, which brought together objects from many different places and times under the loose heading of “affinity.”23James Clifford, “Histories of the Tribal and the Modem,” in The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 189–214. While the Gallery also staged collisions between works with distinct histories, it resisted trying to find unity in formal affinities between objects and instead looked to the distinct mode of sociability that was responsible for the objects coming into its hands in the first place: gift-giving—though not by wealthy donors, but rather by national peoples participating in a common project of self-determination. Whatever shortcomings this ideal may possess, it represented a self-conscious counter-practice to that of imperial art institutions.

- 1Bojana Piškur, “Southern Constellations: Other Histories, Other Modernities,” in Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2019), 18.

- 2Radina Vučetić, “The Exhibition: Exhibitions as Spaces of Cultural Encounter—Yugoslavia and Africa,” in Socialist Internationalism and the Gritty Politics of the Particular: Second-Third World Spaces in the Cold War, ed. Kristin Roth-Ey (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), 93.

- 3The archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro (MCAM), were established with MCAM in 2023. MCAM was founded through the integration of the former Contemporary Art Centre of Montenegro, which itself has included the collection of the Gallery “Josip Broz Tito” since the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1995.

- 4Bojana Piškur and Đorđe Balmazović, “Non-Aligned Cross-Cultural Pollination: A Short Graphic Novel,” in Socialist Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement: Social, Cultural, Political, and Economic Imaginaries, ed. Paul Stubbs (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023), 164.

- 5Bojana Piškur and Đorđe Balmazović, “Non-Aligned Cross-Cultural Pollination: A Short Graphic Novel,” in Socialist Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement: Social, Cultural, Political, and Economic Imaginaries, ed. Paul Stubbs (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023), 165.

- 6The Yugoslav Partisans were members of the resistance force led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia against the Axis powers, primarily Nazi Germany, in occupied Yugoslavia during World War II.

- 7Paul Stubbs, introduction to Socialist Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement, 11.

- 8Marina Blagojević, Knowledge Production at the Semiperiphery: A Gender Perspective (Belgrade: Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, 2009), 33.

- 9Blagojević, Knowledge Production at the Semiperiphery, 33–34.

- 10Raif Dizdarević, Galerija umjetnosti nesvrstanih zemalja “Josip Broz Tito”—Titograd—Yugoslavia, exh.cat. (Titograd: Gallery of Art of the Non-Aligned Countries “Josip Broz Tito,” n.d.), 2.

- 11In 1972, the Solidarity Museum mounted its first exhibit, which was held at the Santiago Museum of Contemporary Art in Chile. Featuring works donated by international artists, the Solidarity Museum was founded under Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government, the world’s first democratically elected socialist administration. In 1978, inspired by the Solidarity Museum, the International Art Exhibition for Palestine took the form of a traveling exhibition that was meant to tour until it could return to historic Palestine. Organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization, the exhibition comprised almost 200 works donated by 200 artists from nearly 30 countries.

- 12The assertion that the Gallery was not established by NAM is a matter of debate, with historical sources offering varying accounts, some of which suggest alternative origins or founders. As Radina Vučetić explains in her essay, “Although the Art Gallery of the Non-Aligned Countries was a Yugoslav-based institution, it was more than a Yugoslav project. At the Seventh Non-Aligned Conference in New Delhi in 1983, non-aligned countries were invited to collaborate in the creation of the Non-Aligned Gallery for the promotion of non-aligned art. The First Conferences of Ministers of Culture of the Non-Aligned and Developing Countries in Pyongyang (1983) and Luanda (1985) further elaborated the activities of the gallery. After a number of meetings of the non-aligned leaders, a decision was taken in New Delhi in 1986 that the ‘Josip Broz Tito’ Art Gallery of the Non-Aligned Countries should become a joint non-aligned institution” (Radina Vučetić, “The Exhibition: Exhibitions as Spaces of Cultural Encounter—Yugoslavia and Africa,” in Socialist Internationalism and the Gritty Politics of the Particular: Second-Third World Spaces in the Cold War, ed. Kristin Roth-Ey (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), 93–94). Vučetić’s analysis, based on evidence from official NAM Summit records, highlights the significant role NAM played in the development of the Gallery. For a more thorough examination of these sources and the contested nature of this information, consult the documents from the NAM Summits. The full archive of NAM Summit records is accessible on the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies website, managed by the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey: http://cns.miis.edu/nam/index.php/meeting/index?Meeting%5Bforum_id%5D=5&name=NAM+Summits

- 13Milan Marović, “Galerija umjetnosti nesvrstanih zemalja “Josip Broz Tito” Titograd,” Informatica museologica 2, nos. 3–4 (October 1990): 47.

- 14Bernard Matemera. Porodica (Family). 1987. White marble, 98 7/16 x 64 3/16 x 62 5/8 in. (250 x 163 x 159 cm). Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro.

- 15Jesmael Mataga, “Local Communities, Counter-Heritage, and Heritage Diversity: Experiences from Zimbabwe,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Heritage and Politics, ed. Gönül Bozoğlu et al. (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2024), 121.

- 16Christine Scherer, “Working on the Small Difference: Notes on the Making of Sculpture in Tengenenge, Zimbabwe,” in African Art and Agency in the Workshop, ed. Sidney Littlefield Kasfir and Till Förster (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 194.

- 17Myrna Ayad, “Overlooked No More: Inji Efflatoun, Egyptian Artist of the People,” New York Times, April 29, 2021, updated May 3, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/29/obituaries/inji-efflatoun-overlooked.html.

- 18Sabrina DeTurk, Street Art in the Middle East (London: I. B. Tauris, 2019), 40.

- 19Yasmin Qureshi, “The Seventh Summit of Non-Aligned Nations,” Pakistan Horizon 36, no. 2 (Second Quarter, 1983): 54.

- 20Non-Aligned Movement, “Declaration of the 7th Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Movement” (New Delhi, March 7–12, 1983), 133, http://cns.miis.edu/nam/documents/Official_Document/7th_Summit_FD_New_Delhi_Declaration_1983_Whole.pdf

- 21Evanthis Hatzivassiliou, “Cyprus at the Crossroads, 1959–63,” European History Quarterly 35, no. 4 (October 1, 2005): 536–37, https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691405056875.

- 22Bojana Piškur, “Southern Constellations: Other Histories, Other Modernities,” in Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned, exh. cat. (Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, 2019), 19.

- 23James Clifford, “Histories of the Tribal and the Modem,” in The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 189–214.