In this text, curator and writer Nina Mdivani revisits the lives and work of Tamar Abakelia (1905–1953) and her student Natela Iankoshvili (1918–2007). She emphasizes how these two Georgian women artists navigated between undertaking state commissions and finding windows of opportunity to oppose the regime and, in the process, creates a genealogy of Georgian artistic practices.

History of Georgian art in the twentieth century reflects two dynamics influenced by the larger history of Soviet occupation.1Georgian occupation by the Russian Empire started in 1783, when the kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti came under its protection, gradually annexing the rest of the country during the nineteenth century. During the Bolshevik Revolution, Georgia was able to achieve a brief period of independence from 1918 to 1922. In 1922, the country was invaded by the Red Army, and it remained under Soviet rule until 1992 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. For an excellent historical overview, see Peter F. Skinner, Georgia: The Land Below the Caucasus; A Narrative History (New York, London, and Tbilisi: Narikala Publications, 2014). On the one hand, official art followed formalist norms of Socialist Realism by submitting to the fiction of a bright Communist future. On the other, this official directive inspired artists to find unique ways of subverting the artistic dictates established by the regime and defiantly pursuing their individual ideas. The work of women artists Tamar Abakelia (1905–1953) and her student Natela Iankoshvili (1918–2007) illustrate these concurrent tendencies.

Abakelia, considered one of the most intriguing Georgian artists of the 1930s and ’40s, worked as a sculptor, illustrator, and costume designer for theater and film. She was made an Honored Artist of the Georgian Socialist Republic in 1942 and is remembered as one of the most authentic Soviet masters of her time. Her family background is integral to an understanding of her life and work. Her father, Grigol Abakelia (1880–1938), was a member of the Highest Court Commission of the Georgian Socialist Republic and, accused of being a member of the Polish secret service and of working for the Polish government, was executed during Stalin’s Great Purge.2Grigol Abakelia, “Stalin’s Lists,” https://stalin.abgeo.dev/dosie/650. Her uncle, Ioseb Abakelia (1882–1938), was a notable professor and founder of the Georgian Institute for the Study of Tuberculosis in 1930. Like his brother, Ioseb was executed after he was accused of being a spy and plotting an act of terrorism against the Soviet regime.3National Parliamentary Library of Georgia, “Biographical Dictionary of Georgia,” s.v. “Ioseb Abakelia,” http://www.nplg.gov.ge/bios/en/00001631/.

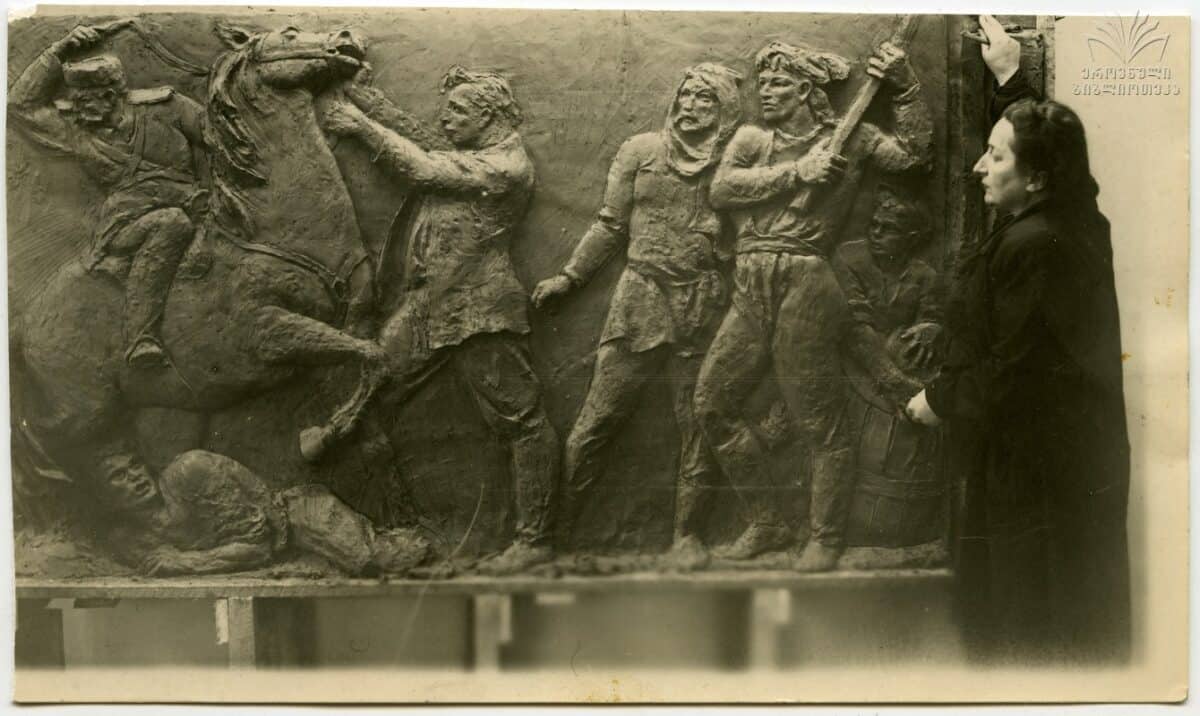

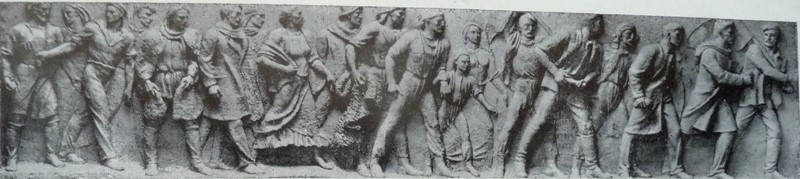

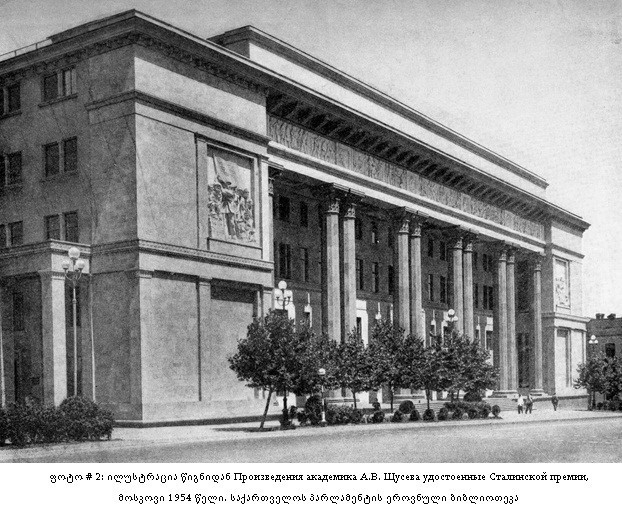

Although Tamar Abakelia’s oeuvre is vast and multifaceted, one project in particular exemplifies her aesthetics while also evoking complex developments in Georgian history.4For more works by Tamar Abakelia, see Kristine Darchia, “The Emancipated Women of Tamar Abakelia,” ATINATI, April 19, 2022, https://www.atinati.com/news/625d9e30b7e78100380ce8a6. In 1936–37, she completed five friezes for the Institute of Marxism-Leninism on Rustaveli Avenue, Tbilisi’s central thoroughfare: Batumi Demonstration under the Leadership of Comrade Stalin in 1902, The Meeting of Partisans with the Red Army, Georgian Agriculture, Industry in Georgia, and Happy Life. Leading artist of the day Iakob Nikoladze (1876–1951), who was Abakelia’s teacher and mentor at the Academy of the Arts and himself a student of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), had been commissioned to design sculptural details for this important building and invited Abakelia to work with him. The Institute was a special project of Lavrentiy Beria (1899–1953), then leader of the Communist Party of Georgia and a close comrade of Josef Stalin. Figures 3 and 4 reproduce archival documentation of two of the friezes. Figure 5 reproduces an archival photo of the Institute in 1941, when it opened. Figure 6 depicts an archival photo of Tamar Abakelia, Beria, and Nikoladze in front of the Institute building at the time it was erected.

As can be seen in figures 3 and 4, Abakelia truthfully adhered to visual formulas associated with Socialist Realism in her depictions of the social progress and triumph of Communism in Georgia. Friezes were widely regarded as marking the revival of the Georgian bas-relief tradition—and were important examples of Georgian monumental-decorative sculpture of the twentieth century. What is visible here is a form of monumentalism that is characteristic of Abakelia’s visual style throughout her career. This return to Renaissance aesthetics is not out of line with the Soviet “promotion” of the physical, emotional, and intellectual well-being of the individual. As postulated in 1934 during the First Congress of Soviet Writers formulated by Andrei Zhdanov (1896–1948) and Maxim Gorky (1868–1936), Socialist Realism represented the single “artistic method” requiring “a true, historically concrete depiction of reality in its revolutionary development . . . [reflecting] the new world, the new person, and a new style.”5V. V. Vanslov and L. F. Deniskova, eds., Iz istorii sovetskogo iskusstvovedeliia i estetic/zeskoimysli 1930-kh godov, (Moscow: 1977), 26.

Abakelia’s friezes depict chains of soldiers and laboring farmworkers symbolically ready to give up their youth and life force for the glory of the Motherland. One important aspect observable here as well as more evident in other works by the artist is that the women stand by the men in equal positions. Women representing strength and power look stern and capable of action; they are not playing secondary roles, but rather are agents of force and change.

Again and again in a diary that she kept from 1918 to 1940, Abakelia emphasizes: “People and their characters interest me the most. First and foremost, I want to know how they look and what they feel.”6Gulnara Japaridze, ed., Tamar Abakelia, Painting, Sculpture, Graphical Works (Tbilisi: Art and Literature, 1967).

Idealized naturalism, a term coined by Georgian art historian Giorgi Khoshtaria, aptly describes the Soviet art of this time.7Maya Tsitsishvili and Nino Chogoshvili, History of Georgian Painting, XVIII– XX Centuries (Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, 2013). In fact, idealized naturalism was a cornerstone of Socialist Realism as it helped to distill the normative and prescriptive ideology of Communism into digestible, optimistic, life-affirming symbols and imagery. One could argue that the ideology of the totalitarian conveyer was not vastly different from that of Ancient Egypt or Greece, both of which were slave-owning societies that produced strong visual imagery to support their ideologic stances. Sociological aesthetics, a term first used by Georg Simmel in 1896, theorizes that aesthetic forms and sociological organization are linked to produce one final, total reality.8See Eduardo de la Fuente, “The Art of Social Forms and the Social Forms of Art: The Sociology-Aesthetics Nexus in Georg Simmel’s Thought.” Sociological Theory 26, no. 4 (December 2008): 344–62.

Bulgarian philosopher Vladislav Todorov has further elaborated on this point, suggesting that “society is a poetic work, which reproduces metaphors, not capital.”9Vladislav Todorov, Red Square, Black Square: Organon for Revolutionary Imagination (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 10. This fairy tale of a healthy new race was one that Abakelia, as an artist within the system, had no choice but to illustrate. We can only surmise how she felt when members of her own family were persecuted by the creators of this gruesome delusion and the Empire that promoted it, but in order to be able to live and work as an artist, she had to produce works that adhered to the Soviet regime’s strict artistic guidelines.

The history of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, originally called the Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin Institute, reflects the larger context of subsequent Georgian history. Construction of the building took place in 1934–38 and cost fourteen million Soviet rubles. Three years later, in 1941, the architect, Alexei Shchusev (1873–1949), was awarded the Stalin Prize, first degree, for his design. During Khrushchev’s Thaw in the mid-1950s to mid-1960s and the dismantling of Stalin’s cult, the Institute removed Stalin from its name. Its rich library became a public library in 1990 but, soon after, was in disarray. During the civil war in Tbilisi in 1991–92, vandals damaged Abakelia’s friezes.10Aleksandre Elisashvili, “IMELI Building in Tbilisi,” Sovlab (blog), November 2011, http://archive.ge/ka/blog/51.

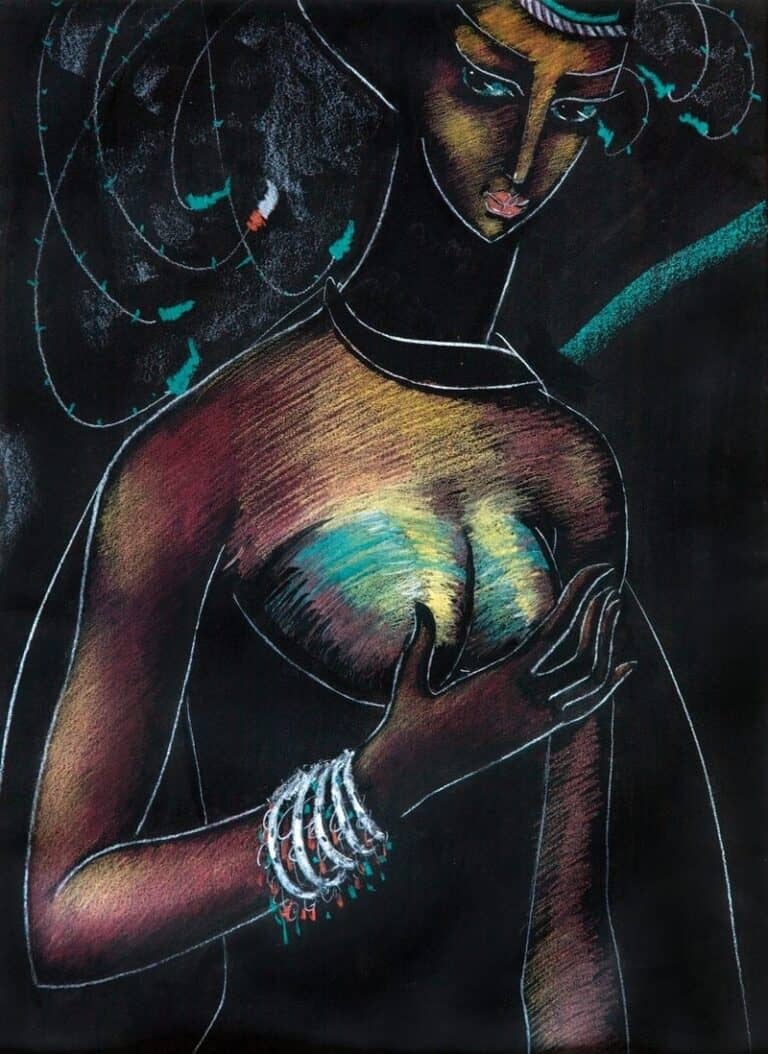

In portraying women as figures of equal strength, Abakelia effectively fought the patriarchy and age-old values in traditional Georgia that insisted upon positioning the male figure at the center of the visual culture produced by Socialist Realism and its male artists.11Abakelia’s major sculptures, such as Family of a Collective Farmer, 1939, and We Will Seek Revenge, 1944, show women as central heroines. Both works attest to the strong, independent feminine presence that lacks any hint of sentimentality. She showed women as equal to if not stronger than their male comrades, a stance in contrast to the traditional sentimentalization of women as gentle mothers and caretakers—and a torch her student at the Tbilisi Academy of the Arts, Natela Iankoshvili, would continue to carry.

The landscapes and cultural landmarks of the Kakheti region in eastern Georgia, where Natela Iankoshvili was born and raised, influenced her work throughout her life. Her parents, Archil Iankoshvili and Mariam Zardiashvili, both teachers from Gurjaani, a town in Kakheti, instilled a love of nature and literature in their three daughters. Iankoshvili started drawing and painting as a child and, in 1937, enrolled in the Academy of Arts in Tbilisi, where she studied with renowned Georgian artists David Kakabadze (1889–1952), Tamar Abakelia (1905–1953), and Sergo Kobuladze (1909–1978). After graduation from the Academy, Iankoshvili actively pursued painting, initially accepting the dictates of Socialist Realism, and from 1930 into the 1950s, building up a substantial body of work. She started to travel around the country, painting her favorite locations. Over time, she drastically changed her style, and at one point, burned over two hundred of her earlier, more traditional works.

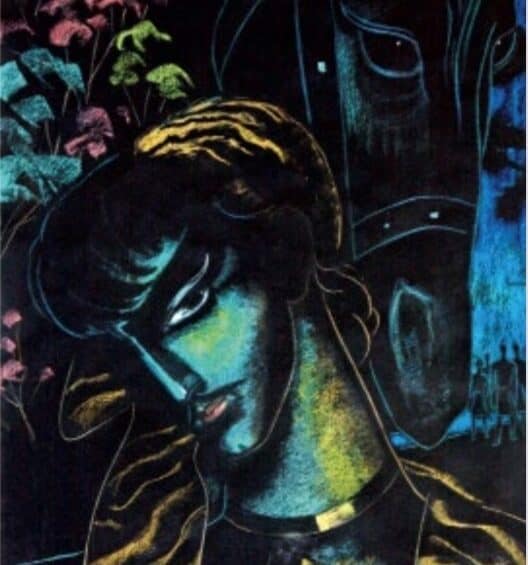

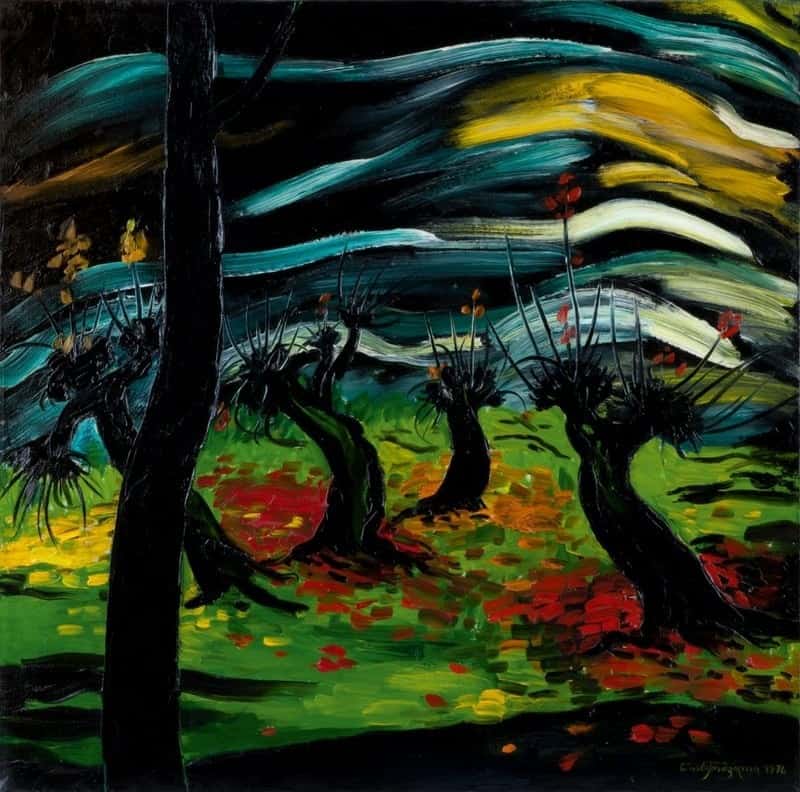

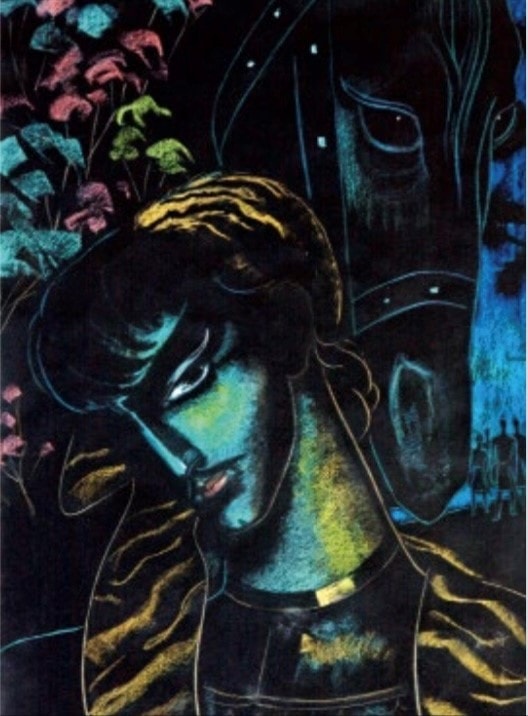

A solo exhibition of Iankoshvili’s work opened at the Tbilisi State (Blue) Gallery in 1960, and she became the first woman painter to have such a showing in this official space. With its more than 250 starkly different, dynamic, progressive, fresh, and emotionally raw works, the exhibition stirred many voices in the Soviet art community. Contemporary art critics aptly compared Iankoshvili’s paintings to compositions by Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) in their sophisticated yet poetic structure and approach. As important Georgian-French art critic Gaston Bouatchidzè wrote, “One does find subdued colors and smiling softness, tenderness in her works, but it is above all in these profound, dark depths where the essence of her paintings is rooted.”12Gaston Bouatchidzè, “Green on Black,” quoted in Natela Iankoshvili: An Artist’s Life Between Coercion and Freedom, Mamuka Bliadze (Berlin: Hirmer, 2020).

Autumn in Kiziki from 1976 (fig. 7) underlines her independence and strength of will, especially when seen in comparison to the docile landscapes of her contemporaries. The expressionist landscape of Kiziki is likewise portrayed with uncommon freedom and exuberance. The silhouettes of trees blend with the black background, connecting the work to that of two Georgian masters: Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918), a self-taught artist and iconic presence in Georgian art history who used a dramatic black background for his still lives and genre scenes, enlivening them with vibrant splashes of color, and Elene Akhvlediani (1901–1975) who, like Iankoshvili, painted landscapes, albeit in much more traditional style, and also used trees as compositional devices.13For more of Elene Akhvlediani’s and Niko Pirosmani’s works, see “‘Wordless Songs’: Fragments from the documentary about the artist Elene Akhvlediani, directed by Ramaz Chiaurelli. 1968,” https://archive.gov.ge/en/elene-akhvlediani-1; and Louisiana Channel, “‘There’s such a clarity and strange beauty about the paintings.’ | 5 Artists on Niko Pirosmani,” YouTube video, 18:53, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0XeditH9xDE. The connection of Iankoshvili to her Georgian roots rather than to Soviet ones is noteworthy. As one contemporary writer noted, she consciously rose against the notion of the artist as chronicler of “nature’s tireless reconstructor and transformer,” as was expected in landscape painting of the time.14Isskustvo, no. 1 (1950): 78. The work’s abstract elements and rich lushness of color intensify the uncanny emptiness of the landscape, which is devoid of figures. To be sure, Iankoshvili seems to have eliminated the surrounding Soviet compatriots, instead focusing on a spiritual communion with the Unknown. The fact that Iankoshvili created her works during the Thaw, a time of relative liberalization and de-Stalinization initiated by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971), made this form of abstraction and her highly individualized method of portraiture not only possible, but also celebrated. In 1976, Iankoshvili became the People’s Artist of Georgia; in 1987, she had an exhibition at the House of Literature in Moscow; in 1996, she received the Georgian Medal of Honor; and in 2000, the Natela Iankoshvili House Museum was founded in Tbilisi, and the artist left all her works to the museum.

Though both Abakelia and Iankoshvili lived and worked in the Soviet period, they were nonetheless able to realize their visions. Neither of them was a dissident in the traditional artistic sense of producing so-called unofficial or underground art, and yet both fought the demands and restrictions of the authoritarian machine. Abakelia was able to produce fundamentally new sculptural representations of women fully equal to their male comrades and to engage in building the country’s artistic future. Iankoshvili continued this line of representation by creating distinct and bold portraits of her contemporaries and then went on to produce even more controversial, abstract, spiritual renderings of the surrounding landscapes. Although neither was a dissident, both held nonconformism as a personal value. Their positions as artists paved the way for underground artists of later decades.

- 1Georgian occupation by the Russian Empire started in 1783, when the kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti came under its protection, gradually annexing the rest of the country during the nineteenth century. During the Bolshevik Revolution, Georgia was able to achieve a brief period of independence from 1918 to 1922. In 1922, the country was invaded by the Red Army, and it remained under Soviet rule until 1992 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. For an excellent historical overview, see Peter F. Skinner, Georgia: The Land Below the Caucasus; A Narrative History (New York, London, and Tbilisi: Narikala Publications, 2014).

- 2Grigol Abakelia, “Stalin’s Lists,” https://stalin.abgeo.dev/dosie/650.

- 3National Parliamentary Library of Georgia, “Biographical Dictionary of Georgia,” s.v. “Ioseb Abakelia,” http://www.nplg.gov.ge/bios/en/00001631/.

- 4For more works by Tamar Abakelia, see Kristine Darchia, “The Emancipated Women of Tamar Abakelia,” ATINATI, April 19, 2022, https://www.atinati.com/news/625d9e30b7e78100380ce8a6.

- 5V. V. Vanslov and L. F. Deniskova, eds., Iz istorii sovetskogo iskusstvovedeliia i estetic/zeskoimysli 1930-kh godov, (Moscow: 1977), 26.

- 6Gulnara Japaridze, ed., Tamar Abakelia, Painting, Sculpture, Graphical Works (Tbilisi: Art and Literature, 1967).

- 7Maya Tsitsishvili and Nino Chogoshvili, History of Georgian Painting, XVIII– XX Centuries (Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, 2013).

- 8See Eduardo de la Fuente, “The Art of Social Forms and the Social Forms of Art: The Sociology-Aesthetics Nexus in Georg Simmel’s Thought.” Sociological Theory 26, no. 4 (December 2008): 344–62.

- 9Vladislav Todorov, Red Square, Black Square: Organon for Revolutionary Imagination (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 10.

- 10Aleksandre Elisashvili, “IMELI Building in Tbilisi,” Sovlab (blog), November 2011, http://archive.ge/ka/blog/51.

- 11Abakelia’s major sculptures, such as Family of a Collective Farmer, 1939, and We Will Seek Revenge, 1944, show women as central heroines. Both works attest to the strong, independent feminine presence that lacks any hint of sentimentality.

- 12Gaston Bouatchidzè, “Green on Black,” quoted in Natela Iankoshvili: An Artist’s Life Between Coercion and Freedom, Mamuka Bliadze (Berlin: Hirmer, 2020).

- 13For more of Elene Akhvlediani’s and Niko Pirosmani’s works, see “‘Wordless Songs’: Fragments from the documentary about the artist Elene Akhvlediani, directed by Ramaz Chiaurelli. 1968,” https://archive.gov.ge/en/elene-akhvlediani-1; and Louisiana Channel, “‘There’s such a clarity and strange beauty about the paintings.’ | 5 Artists on Niko Pirosmani,” YouTube video, 18:53, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0XeditH9xDE.

- 14Isskustvo, no. 1 (1950): 78.