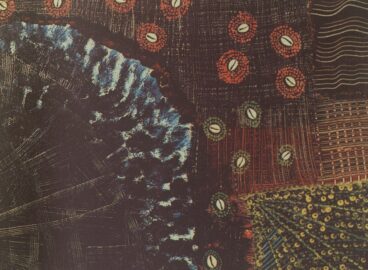

“Seyni Awa Camara doesn’t belong to any artistic school,” wrote art critic Massamba Mbaye in 2016.1Massamba Mbaye, Terre de lumière: Seyni Awa Camara ([Dakar]: Musée Khelcom, 2016), 7. She resists any classification and has always considered herself a singular artist, whether in the context of her own country or in that of the international art scene (fig. 1). As Mbaye stresses, Seyni Awa Camara (Senegalese, born c. 1945) could easily have been excluded from the history of art built in the aftermath of independence in Senegal under Léopold Sédar Senghor’s patronage and with state support, when artists were trained at the Dakar “école des arts,” mostly as painters. Except for Younousse Seye (Senegalese, born 1940), no women participated in the exhibitions organized to promote national Senegalese art. Younousse Seye was the only woman to display in Dakar (solo exhibition, Théâtre Daniel Sorano, 1977), Algiers (Pan-African Festival, 1969), and Paris (Art sénégalais d’aujourd’hui, 1974). And contrary to most men, she did not benefit from academic training; she learned from her mother who worked as a batik dyer. Camara also inherited her skills from her mother, who was a potter in Casamance (Senegal). Both artists grounded their practices in family knowledge and later developed in more personal directions. Camara certainly gained more attention than Seye over time, especially outside of Senegal. At the turn of the 1990s, her bold statues were displayed in Paris (Magiciens de la terre, 1989), Las Palmas (Africa Hoy, Africa Now, 1992), and Venice (Biennale Arte 2001—Plateau dell’Umanità, 2001). They are now part of important collections such as the National Museum of Art (Oslo), the Theodore Monod Museum in Dakar (see fig. 4), and the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (Paris), as well as held in many private collections, some of which are in Senegal (Jom in Dakar and the Musée Khelcom in Saly Portudal). If her creations have stood the test of time, they have also crystallized many of the binary opposites that still structure the art world’s expectations, such as art and craft or the collective and the singular, or the caution deemed necessary by the West in validating any artistic process developed in the so-called peripheries. Looking at the history of global contemporary art from the perspective of Camara’s work and career reveals the ways in which globalization operates, especially regarding women artists from Africa.

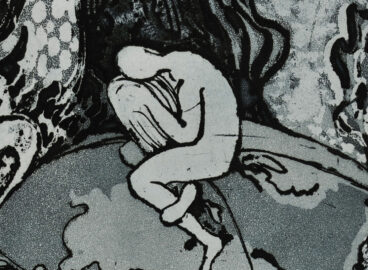

Seyni Awa Camara’s figures are striking, and yet they are not meant to please or seduce. They stand free, strongly anchored by their feet, and are sometimes double-headed. With their large smiles, their visible teeth, and their bulging eyes, they often look provocatively happy. Their size varies from a few inches to several yards high, but they are always frontal and hieratic; they are sometimes covered with smaller figures, who cling to their torsos and legs (fig. 2).

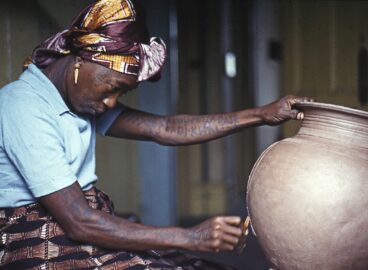

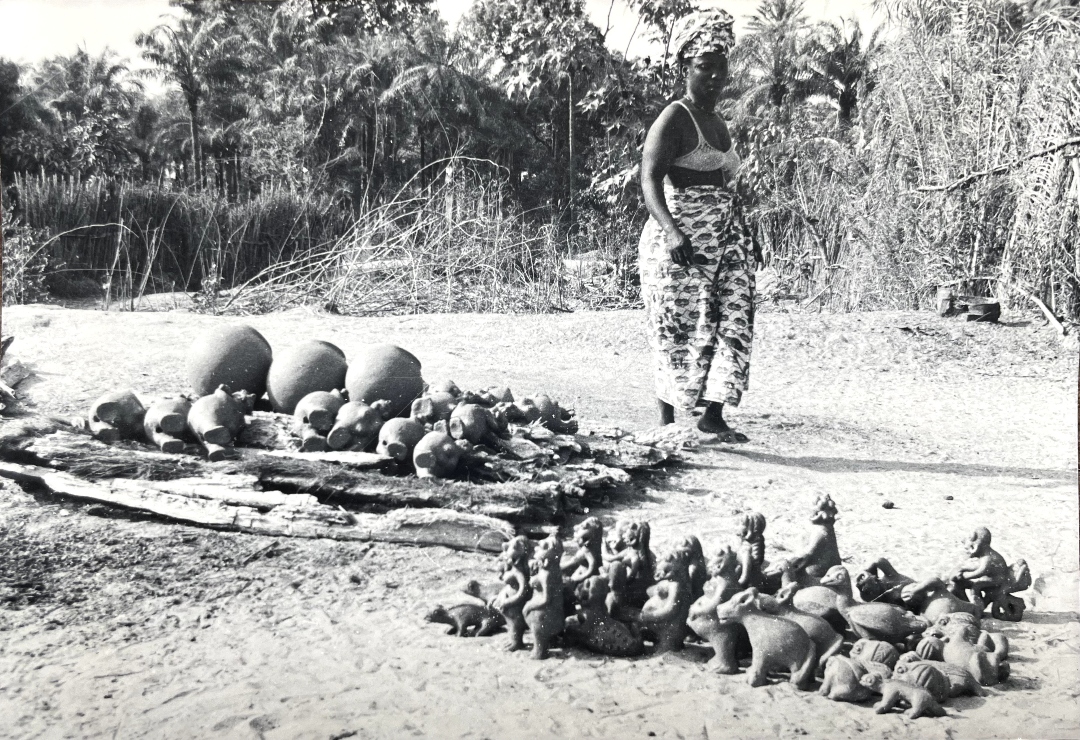

When Camara started making these sculptures in her village in Bignona (Casamance, Senegal), people were scared; she could not show them publicly. Michèle Odeyé-Finzi recalls that when she met the artist in the early 1980s, Camara was selling utilitarian pots in the local market.2Michèle Odeyé-Finzi, Solitude d’argile: Légende autour d’une vie; sculptures de Seyni-Awa (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1994). She was keeping her personal sculptures at her home outside the village in a special room that she had dedicated to them. There, statuettes ranging from maternity figures to zoomorphic ones, small frogs juxtaposed with large cats, trucks, or monkeys (fig. 3), covered the floor. They were made of clay of various shades depending on how they were fired, which is less the case today.

Mystery and rumor surrounded her activities and continue to do so: some wonder if she is still alive and if it is she or rather a sibling who is making the sculptures sold today. A triplet, she was about twelve years old when she disappeared into the forest with her two brothers. As the story goes, they stayed hidden for about four months and geniuses protected them and taught them how to model clay. When the three children finally returned to the village, one of them (Allassane) was carrying a sculpture that he said the forest geniuses had taught him to make. Camara told anthropologist Michèle Odeyé-Finzi that all three of them had been initiated into art by mystical forces—a story that perfectly fit the expectations of the West. It only needed to be relayed by the art world to become magical, which happened in Paris in 1989 at the Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the World) exhibition.

A lot has been said and written about Magiciens de la Terre as it betrayed many of the hopes it had raised of being the first truly inclusive and international exhibition. According to the Centre Pompidou, which mounted the show, one hundred artists from all over the world were represented in the French capital: fifty from the West and fifty from “the rest” or “non-Western countries.”3Magiciens de la terre exhibition page, Centre Pompidou website. This Eurocentric division was reinforced by the selection criteria: the works of artists from Asia, South America, and Africa were the result of religious, rural, or mystical practices, while those from Europe and the United States were technological, conceptual, and often self-reflexive in nature. Global modernisms were excluded as curator Jean-Hubert Martin feared they would be considered mere copies of Western styles.4In a conversation with Hans Belting, Jean-Hubert Martin stated: “I often saw the école de Paris being assimilated [in Africa], for example. If I had shown these works in the exhibition, everyone would have said they were imitations of Western art of the 1950s, say. The trick was that I was looking for, and found, something quite different.” Jean-Hubert Martin, “Magiciens de la terre: Hans Belting in Conversation with Jean-Hubert Martin,” in The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds, ed. Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg, and Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 209. The “Picasso syndrome” theorized by Partha Mitter for Indian artists easily applies to any artist from the Global South, and instead of presenting artists who questioned modernism from different perspectives (such as those affiliated with the Dakar School or Laboratoire Agit’Art in Senegal), Martin and co-curator André Magnin chose artists whose work implicitly reenacts the opposition between the “primitive” and the “modern.” This dual approach revived the primitivistic fashion that took place in Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the European avant-gardes drew inspiration from the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, hence contributing to their paradoxical integration into the Western canon.5Partha Mitter, “Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery,” Art Bulletin 90, no. 4 (December 2008): 537. The “problem” with this exhibition was not the art or the artists, but rather the burden of representativity it imposed on the artists as their art was led to incarnate one part of the world in comparison or contrast with another.

Still unknown within the contemporary art scene, Camara’s statues were exhibited next to those of Louise Bourgeois (American, born France. 1911–2010), one of the few “great women artists” at the time, to quote art historian Linda Nochlin.6Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, 50th anniversary ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2021). Bourgeois served as symbolic validation for Camara, a gesture that was reiterated in 1996 when Bourgeois was invited to write about Camara for a book titled Contemporary Art of Africa: “I recognize her originality and a certain beauty. Now, beauty is a dangerous word because notions of ‘beauty’ are relative. So let me be very clear: the work gives me pleasure to look at. As one artist to the other, I respect, like and enjoy Camara.”7Louise Bourgeois, “Seni Awa Camara,” in Contemporary Art of Africa, ed. André Magnin and Jacques Soulilou (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 54. Camara always considered herself an artist even though she lacked academic training (in the 1980s in Senegal, only 30 percent of girls went to school, and 93 percent of those attending art school were men8Abdou Sylla, Arts plastiques et état au Sénégal: Trente-cinq ans de mécénat au Sénégal (Dakar: Université Cheikh Anta Diop, 1998), 125.). “She enjoyed or missed the privilege of going to art school (a blessing in disguise),” continued Bourgeois. “But there need be no apologies for naïveté or technical shortcomings. Her genuinely expressive figures have a coherence in style.”9Bourgeois, “Seni Awa Camara,” 54.

Camara started making sculptures when she was six years old. She learned from her mother and used to hide zoomorphic figurines in the burning oven among the pots and amphoras her mother was making to be sold at the local market. At the age of fifteen, she was forced to marry a much older man and stopped creating. Though she was pregnant four times, she never gave birth; moreover, she fell seriously ill and had to undergo several operations. Like too many women in Senegal and around the world who are forced to marry at too early an age, Camara had to fight. She came back to art when she left her husband and found in sculpture a way to survive and rebuild herself. Her creations are testament to the power of a woman who not only persisted in a practice many considered strange or marginal, but also was able to make sense of it. She fashioned a unique style and, in the process, built herself a home and secured stable sustenance for her family.

Drawing inspiration from her surroundings, Camara has been prolific and consistent, often dedicating her efforts to pregnant figures and expressions of the maternal. In 1989, for instance, she showed a series of feminine statues covered with small smiling figures that seemed to be budding from them. The energy and power of this work results from accumulation, from the repetition of motifs that creates a tension and challenges any easy apprehension of their meaning. Faces suddenly appear on a belly or the knees, radiating like a sun. Camara’s anonymous characters wear jewelry, they have scarifications and elaborate hairstyles. They command our attention with their round eyes, but yet repel us with their silent, empty stares.

Camara believes these figures can heal both herself and others. Indeed, she once cured a couple who could not have children, helping them give birth to twins, as she recalls in Fatou Kandé Senghor’s film Giving Birth.10Fatou Kandé Senghor, Giving Birth (Dakar: Waru Studio, 2015), video with color, sound, 30 min.Healing takes time, as does the making of sculptures, which in Camara’s case, begins with the fetching of clay from the marigot (swamp) and is followed by the fine grinding of shellfish and the mixing of the two ingredients.

Once the modeling has been completed, the firing stage, which takes place in the open air of the concession yard, begins (fig. 5). As is always the case with ceramics, some pieces break or explode, while others endure the flames and come out just fine. Camara can count on the help of her family and is often shown surrounded by the young men (her second husband’s sons) who work for her, obeying her orders, preparing the pellets she progressively adds to her hollow figures (fig. 8). Though Camara trains those who assist her, she does not intend to pass down her style or her secrets, as she states in Kandé Senghor’s film. Her art is personal, unique; she believes she received a gift from God and that when she dies, her production should stop.

Camara has been living from her art since the 1990s, but to her great regret, she sells mostly to foreigners. As she recounted in 2006: “People don’t know me in my own country. I survive thanks to foreigners’ orders. They buy my work and then they leave. My own country ignores me. They don’t know who I am.”11Seyni Awa Camara, interview by Fatou Kandé Senghor, in Giving Birth. Fortunately, things have changed since then. The Théodore Monod African Art Museum organized a show of her work in 2018 and acquired some of her statues. The Dak’Art biennial included several of her ceramics in the national pavilion the same year, including her in a national survey of art, and her fame continues to grow within the Western art market.

I wish to thank Francesco Biamonte, Bassam Chaïtou, Michèle Odeyé-Finzi, El Hadji Malick Ndiaye, and Fatou Kandé Senghor for the information and images they so generously shared with me for this essay.

- 1Massamba Mbaye, Terre de lumière: Seyni Awa Camara ([Dakar]: Musée Khelcom, 2016), 7.

- 2Michèle Odeyé-Finzi, Solitude d’argile: Légende autour d’une vie; sculptures de Seyni-Awa (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1994).

- 3Magiciens de la terre exhibition page, Centre Pompidou website.

- 4In a conversation with Hans Belting, Jean-Hubert Martin stated: “I often saw the école de Paris being assimilated [in Africa], for example. If I had shown these works in the exhibition, everyone would have said they were imitations of Western art of the 1950s, say. The trick was that I was looking for, and found, something quite different.” Jean-Hubert Martin, “Magiciens de la terre: Hans Belting in Conversation with Jean-Hubert Martin,” in The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds, ed. Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg, and Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 209.

- 5Partha Mitter, “Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery,” Art Bulletin 90, no. 4 (December 2008): 537.

- 6Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, 50th anniversary ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2021).

- 7Louise Bourgeois, “Seni Awa Camara,” in Contemporary Art of Africa, ed. André Magnin and Jacques Soulilou (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 54.

- 8Abdou Sylla, Arts plastiques et état au Sénégal: Trente-cinq ans de mécénat au Sénégal (Dakar: Université Cheikh Anta Diop, 1998), 125.

- 9Bourgeois, “Seni Awa Camara,” 54.

- 10Fatou Kandé Senghor, Giving Birth (Dakar: Waru Studio, 2015), video with color, sound, 30 min.

- 11Seyni Awa Camara, interview by Fatou Kandé Senghor, in Giving Birth.