In this text, social theorist and researcher Jan Sowa and curator Joanna Warsza examine the place of Central and Eastern Europe in discussions of colonialism, postcolonialism, and decolonization, and consider examples of recent art and curatorial projects (both their own and those of colleagues) in this dialogue.

In the endless Zoom calls, one has to navigate the time zones. Setting your meeting to CET—Central European Time—you see many cities listed, including Amsterdam, Stockholm, and Rome, but almost never Tirana or Warsaw, which are part of the former Eastern bloc. If you schedule a call in Riga, Helsinki comes up as your time mark. And it is not only tech giants in Silicon Valley who see Europe through a Western prism but also many critical thinkers.

“Something that wants to be, but cannot, that wants to express itself, but is unable to,” wrote Witold Gombrowicz about Poland.1Witold Gombrowicz, Diary, trans. Lillian Vallee (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 204. “A space torn between the feeling of superiority and inferiority both towards the West, as well as the East,” claims feminist scholar Maria Janion in Uncanny Slavdom.2Maria Janion, Niesamowita Słowiańszczyzna: fantazmaty literatury (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2007). This paradoxical mix of under- and overestimation of its own importance fuels the current right-wing turn in Eastern Europe,3We use two distinct yet also overlapping terms: “Eastern Europe” as it was drawn during the Cold War and “Central-Eastern Europe,” which marks a smaller space within the East. What is labeled generally as “Eastern Europe” contains three distinct areas: (1) Central-Eastern Europe, which is situated between the Baltic Sea in the north, Germany in the west, and the Danube River in the south; (2) South-Eastern Europe (or the Balkans), which is south of the Danube; and (3) European East, which comprises most of the European part of Russia along with the states situated in the Caucasus and the eastern parts of Ukraine and Belarus. In this essay, for historical reasons, the term “Central-Eastern Europe” takes a predominantly Polonocentric perspective, but it should not be confused with the German notion of Mitteleuropa, whichmarks a smaller space of strong German political, cultural, and economic influence within Central-Eastern Europe. predominantly in Poland and Hungary. Its symbolics—built on myths of past grandeur and regional conquests, while simultaneously denying its own colonial mindset—might not come as a big surprise given the region is obsessed with its own history but reluctant to critically examine it.

What is the place of Eastern Europe in postcolonial and decolonial debates and in the larger colonial project? How to tackle this region that has been both oppressed, having endured centuries of serfdom, and an oppressor, aspiring to join the West in the colonization of Africa—and that today often cites postcolonial theory in its nationalist agenda? Polish right-wing government celebrates the country’s exceptionalism and victimhood in order to sustain an anti-immigration stance, in what curators Ekaterina Degot and David Riff call a “perverse decolonization”—or strategy in which former colonial dependence and semi-peripheral inferiority foster obscure ways to preserve one’s allegedly endangered way of life.4Ekaterina Degot and David Riff, “Perverse Decolonization,” in Stealing from the West: Pluriversale VII, 20-9–10-12-17, https://www.adkdw.org/downloads/PLU7_BOOKLET_WEB.pdf.

Degot and Riff describe perverse decolonization as an “emancipative process gone wrong but also bent to fit the rage of new, transgressive appetites,” tracing it in Eastern European politics.5Ibid., 71. A recent example of such curatorial perversity is manifested at the Warsaw’s Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), which is implementing a sort of “state art” in the name of a neo-traditional future (the mix of reactionism and futurism is very characteristic of the agenda of perverse decolonization), with more cultural institutions following suit.

Eastern Europe’s historical and symbolic position as part of Europe but not exactly—that is, its relative absence in discourse equating Europe with Western Europe—complicates the asymmetry of the so-called Global North and Global South, to which some propose adding the Global East.6Praktyka Teoretyczna 38, no. 4 (2020), https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/prt/issue/view/1882. As much as Europe’s violent colonial mindset has been shared and embodied across the whole continent, its colonial past has not—because the fundamentals of it were first exercised locally, mostly in its semi-peripheral Eastern and Southern parts, which submitted to Western exploitation, and then perpetuated further. Thus Eastern Europe shares the condition of being complicit in the system of imperialism and colonization, while at the same time serving as a first training ground for its implementation; in effect, it has been both racializing and racialized.7For analyses of mechanisms of racialization, see Livio Boni and Sophie Mendelsohn, La vie psychique du racisme (Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2021).

Hungarian geographer Zoltán Ginelli, who founded the Facebook group Decolonise Eastern Europe, defines various local dilemmas: “Eastern Europeans historically have been racialized as ‘non-white’ while they themselves have produced a semi-peripheral position which was ‘not-quite-white.’ They supported various colonial projects and at the same time the region was seen as a colonizable space. They were often cast as ‘non-whites,’ but wanted the benefits of whiteness.”8Zoltán Ginelli, email message to authors, [25 March 2021]. See also https://www.is.uw.edu.pl/en/research-and-conferences/research/echoes. This complex idiosyncrasy might be one of the reasons why Eastern Europe sometimes falls out of the global picture, and especially the US-grounded debates concerning the “Eurocentric” perspective, which might be better described as “Western-centrism” or “Occidentalism.” It was already materially diagnosed by Immanuel Wallerstein through his World-system theory, which points to the center-periphery divide of the continent,9Immanuel Wallerstein, World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction, Duke University Press, 2004 and yet there is also a symbolic dimension to it, for the West has controlled most of the discursive tools of theory and history (and art). We believe that simply applying these tools in Eastern Europe is not enough. The ideas of Eurocentrism and European whiteness need to be decentered. The European critical spectrum calls for more in-depth analysis of a vernacular experience of the post-communist and post-socialist legacy across the eastern part of the continent, including, for example, the participation of ex-Yugoslav countries in the Non-Aligned Movement, the inner relations between the older and newer countries, and the long and complex coexistence with the Jewish and Roma populations.

The Inner European colony

According to Timea Junghaus, curator and executive director of the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC), Europeans like to look for colonies somewhere far, and outside. But they fail to see [the] long-term “inner colonized minority” that has existed within Europe since the 14th century.”10Timea Junghaus, See also: http://politicalcritique.org/cee/hungary/2017/interview-timea-junghaus-budapest-international-centre-roma-culture-berlin-eriac-decolonization/ The Romani are Europe’s largest and oldest ethnic minority, counting more than twelve million people. This transnational, trans-European, Roma and Sinti community, with nomadic sensibility manifesting in no state-forming desires or territorial claims, has long been present across Europe, especially in its Central, Eastern and Southern parts. It has equally long resisted both the European ideas of nation state, but also the daily mechanisms of “othering” being, until today, heavily subjected to daily racialization. As scholars Nidhi Trehan and Angéla Kóczé have written, “From the British Isles to the Balkans, if you are marked as being Romani [. . .], there is little respite from the violence that envelops you—physical, symbolic, epistemic—as a consequence of persistent and deeply embedded antigypsyism within European cultural enclaves.”11Nidhi Trehan and Angela Kocze, “Racism, (neo-)colonialism and social justice: the struggle for the soul of the Romani movement in post-socialist Europe,” in Racism Postcolonialism Europe, eds.Graham Huggan and Ian Law (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), 50–74, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300584669_Racism_neo-colonialism_and_social_justice_the_struggle_for_the_soul_of_the_Romani_movement_in_post-socialist_Europe.

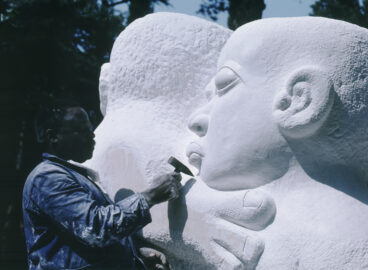

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas is a Polish-Romani artist, activist, and educator who is turning the tide of social injustice by decolonizing Roma culture. In her multifaceted work, she addresses anti-Romani stereotypes and engages in building an affirmative iconography of Roma communities. Her vibrant sculptures, paintings, spatial objects and large-format textiles, small altars, and pictorial collages, depict scenes of everyday life in Roma settlements, such as the village of Czarna Góra at the foot of the Tatra Mountains in Poland, where she herself lives and works. In recent years, Mirga-Tas has been also building an affective archive of Romani herstory. She creates patchworks and textiles from fragments of different fabrics by, as she describes it, “throwing the material into the painting.”12Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, See also: https://eriac.org/my-feminism-does-not-shout-but-it-tells-stories-malgorzata-mirga-tas-and-edis-galushi-in-conversation-with-joanna-warsza/ Many of the fabrics she sews into her paintings—bits of skirts, scarves, or shirts sewn onto curtains, drapes, bedclothes or rags—were taken directly from the people depicted, who are close to her. “Shall I sell this dress, give it to someone, or do you want it for a painting?” her mother often asks. The materials she employs literally carry history, bearing the traces and energy of life and use.

Mirga-Tas calls herself a feminist and practices minority feminism, although, as she says, “Many women around her view this term with suspicion.”13Ibid. Roma feminism—according to researcher Ethel C. Brooks—does not aim at cutting women off from their backgrounds or cultural baggage but instead works within a specific context in various ways.14Ethel C. Brooks, See also: The Possibilities of Romani Feminism, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/665947 At local and private levels, this often means attempting to change the perceptions and/or behaviors of men. On a structural level, it means fighting against nationalism, confronting dysfunctional social behaviors, and combating racism and preconceptions stemming from a mixture of fantasy and disdain.

For Mirga-Tas, working with the notion of identity—Romani, female, and Central-European—and rooting it in the experience of injustice, is an affirmative and empowering methodology. For the artist, it is only through being situated in a particular context rather than at a distance from it that one can contribute to a more complex self-understanding of Europe’s ubiquitous inner coloniality without colonies.

Serfdom East of the River Elbe

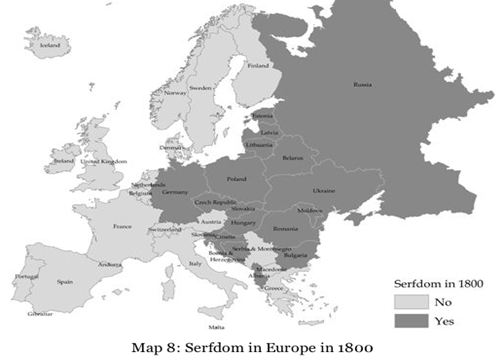

Among the historical implications defining Central-Eastern Europe is the long-term existence of serfdom, a feudal form of forced dependence and oppression, which disappeared in Western Europe in the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries as an effect of economic transformation and peasant revolts. Scholars such as Anibal Quijano, Immanuel Wallerstein, and Perry Anderson show that in early modern times, the South-Eastern part of the European continent was integrated into the capitalist world economy. While the core of Western Europe was turning to predatory expansion overseas, a kind of internal colonial expansion happened in the East: serfdom developed and persisted in Eastern Europe till the end of the nineteenth century, turning the region into one of the first historically peripheral zones.

The Elbe River can be seen as a symbolic border between the development of slavery and serfdom. East of the Elbe, serfdom persisted till the end of the nineteenth century; west of it, the slave trade was delegated overseas and developed through colonization and modernization. European capitalism was thus built on various kinds of unfree labor inherent to both systems. And ironically, the Elbe once marked the border of the Roman Empire, and later, that of the Iron Curtain.

In the sixteenth century, the erstwhile kingdom of Poland and its nobility played a key role in further extending the system of serfdom of peasants deep into South-Eastern Europe. Poland’s attempts to build its own empire by dominating Lithuania and annexing vast areas of what is now Ukraine and Belarus, are still described in the Polish language using the colonial term Kresy, or vast, empty border territories (from the Polish kres, which translates as “end, boundary”). Parallelly, enslavement of the Romani people persisted in Romania till the mid-nineteenth century.

Aspiring to the Colonial Mindset

Maria N. Todorova famously said in her 1997 book “Imagining the Balkans” that the Western Europe is a standard that the rest has to position itself to.” Eastern Europe was thus following its Western counterpart in its own violent colonial ambitions, often after regaining independence from the European inter-partition/colonization established at the end of World War I. One of the most important blind spots in the Eastern European historical narrative is an almost complete lack of recognition of the region’s colonial aspirations and episodes—and its ambition to join the colonial race overseas. For example, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (present-day Latvia) established a colony on the island of Tobago in the seventeenth century.

In 2020, Dutch-Caribbean artists Quinsy Gario and Jörgen Gario staged a performance in the city of Kuldīga at the monument of Latvian-German duke Jacob Kettler, a slave trader and owner of colonies in Tobago and Gambia. The monument commemorating Kettler was inaugurated in 2013 as part of a nation-building narrative, as if, writes Margaret Tali, “elevating Latvia to the position of a former colonial force alongside its Western European counterparts. Rather a regrettable historical fact, this past has become desired.”15Margaret Tali, “Remembering and Re-imagining Histories to Repair, BLOK, posted December 24, 2020, http://blokmagazine.com/remembering-and-re-imagining-histories-to-repair/.

Their performance was a warning against a repetition of violence in memory work rather than yet another celebration of the colonial mind. Tali further captures the asymmetry in the colonial legacy on the two sides of the former Iron Curtain. To her, Garios’ performance disturbed “the pride with which most Latvians continue to look at this history by showing relationships between violence and the transatlantic economy.”16Ibid. Such a troublingly affirmative look is of course nothing more than an expression of a colonial mind. The questions arise: Now that Eastern Europe’s colonial past has come to light, how do we address it in a decolonial way—in an open, critical, and vulnerable shared narration with a Global South—rather than in a way that perpetuates neo-hegemony? And how, at the same time, do we avoid denying the fact that Eastern Europe has also been colonized within the capitalist modern world-system: from the Baltic trade dominated by the Dutch starting in the sixteenth century to the neoliberal transformation of the Soviet bloc in the 1990s?

The history of the Polish Maritime and Colonial League, researched by Polish artist Janek Simon for more than a decade, shows that the aspiration to join the project of Western colonialism is not only a part of the distant past, for its consequences linger today. Poland, along with many countries of the former Eastern bloc, regained independence in 1918 (after 150 years of partition between Prussia, Austria, and the Russian empire), and with it, access to the Baltic Sea. An organization called the Colonial and Maritime League was created to support the development of a merchant fleet and to secure overseas possessions. It boasted a membership of one million people in 1939, lobbied to get possession of Togo (the argument being that a share of German colonial domains should go to Poland after Prussia lost some of its territory), and started systemic land acquisitions in Paraná in southern Brazil, and Madagascar.17For more, see Joanna Warsza and Jan Sowa, eds., Everything Is Getting Better, exhibition reader. (Berlin: SAVVY Contemporary, 2017).

Simon’s research, ongoing since 2006, consists of assembling counter-archives, of displaying and contextualizing magazines and other archival items of this period. What the artist’s multilayered and well-informed installations poignantly display is that the mindset and ideas propagated by the Maritime and Colonial League linger today. The history “that never was” has direct links to latent racism in Poland and to some neocolonial ideas such as Intermarium—a geopolitical federation of Eastern European bloc countries led by Poland from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and advocated by the current right-wing government.

Coloniality without Colonies? 18Olga Stanisławska, “After ‘Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, Raj, (Paradise), 2012,’” posted March 2020, https://obieg.pl/en/172-emma-wolukau-wanambwa-paradise-2012.

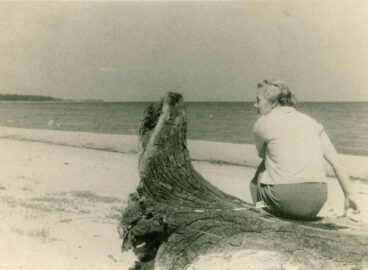

While many new Eastern European nations joined in the humiliating partition of Africa in the interwar period, some European citizens found themselves on the African continent as refugees. Scottish-Ugandan artist Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, in her long-term project Paradise, tells the story of Koja—one of the displaced people camps established in Uganda by the British during World War II. Around seven thousand Poles and Ukrainians lived in the Uganda Protectorate between 1941 and 1952. Wolukau-Wanambwa focuses on the history of the governance of colonial sexuality, and the violent elimination of children born from the relationships between refugees and the local population: “Whenever a Polish woman fell pregnant by a local man, their baby was killed at birth and discarded as medical waste.”19Ibid. The story is meticulously re-created by the artist through absence rather than presence.

Wolukau-Wanambwa photographs the presumably empty landscapes becoming heavy with meaning through an accompanying narration: “My aim has been to investigate the omissions, elisions and effacements and the complex of strategies that colonial discourse employs in order to produce the colonised subject.”20Ibid. The story of Africa’s East European refugees needs to be told again and again—especially now, when so many of the region’s nation states are imperiled by fear of migration and the image of a post-migrant society.

Post-Soviet Chic and Rip-Off Fashion

The inferior place that Eastern Europe still occupies in the theater of European prestige has taken an interesting turn in recent years. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the collapse of state socialism, and the spread of capitalism eastward, street fashion began to change. People started to massively import or produce fake brands and symbols of an unattainable lifestyle: Abibas, not Adidas, and Pama, not Puma, among others. Counterfeit and bootleg products were suddenly everywhere, together with secondhand stores full of Western cast-off clothes.21See Magda Szcześniak, “Fake it Till You Make it: The Trouble with the Global East Category,” Praktyka Teoretyczna 38, no. 4 (2020), https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/prt/article/view/28150/25458.

In early 2010, Vetements, a fashion brand co-run by designers who grew up during the Abkhazian conflict in Georgia, introduced the concept of post-Soviet chic, with its baggy looks and label-hunger, to the Western markets. Originally the oversize clothes and rip-off items came from necessity, from poverty and the domestic war. Back then, DHL T-shirts that made it to the streets of Warsaw, Kyiv, Tbilisi, or Riga were cherished for a couple of years. Today’s cult fashion brands of Gosha Rubchinskiy, Vetements, and Balenciaga offer a look that, for some, evokes memories of poverty, but for others, are marks of luxury. Vera Zalutskaya, a Polish-Belorussian curator investigating the hype behind what she calls “a sad sport jumpsuit” claims that those trends “have been first symbolically approved by the West only to come back to East Europe as mega-cool, although just before they were a sign of war, rather than a choice.”22See https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=4153124098033927&ref=watch_permalink. Today these brands are worn in both the East and the West, but only by those who can afford them.

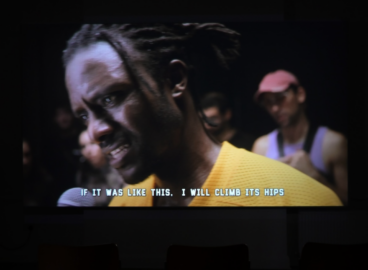

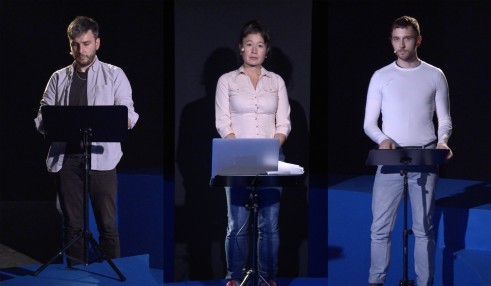

Artists Hito Steyerl, Miloš Trakilović, and Giorgi Gago Gagoshidze in their installation-cum-lecture performance brilliantly traced the genealogy of this new fashion and the symbolic split of the East and West of Europe. In MISSION ACCOMPLISHED: BELANCIEGE, they deconstructed how the East sold the West the look of co-optation and appropriation of the aesthetic of the poor, mixed with memes, social media, and the EU catwalks. “When you look at the ironic usage of fakes or bootleg among young people in Western metropolises, it comes from a position of privilege,” says Albanian-German artist Anna Ehrenstein, who compares today’s hype culture with the logomania of the 1990s. For her, the question isn’t what is real and what is fake, but rather who can afford to wear either—and if the bootleg industry deserves both space and credit.23See Liza Premiyak, “Ripoff fashion ruled Eastern Europe’s label-hungry ’90s. Why are designers celebrating it now?,” Calvert Journal, posted March 5, 2020, https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/11671/knock-off-fashion-eastern-europe-national-identity.

Many residents of Albania, Kosovo, Bosnia, and Georgia, when speaking of Europe, mean some distant place; while they or their relatives construct the roads, the infrastructure, or the health system of this remote continent and thus literally keep it alive. And when those same people want to call home to, for example, Tirana, they check in on Zoom only to find out that home actually lies in Milan.

This text evolved from research connected to the exhibition and associated reader Everything Is Getting Better: Unknown Knowns of Polish (Post)Colonialism (SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin, 2017, and La Colonie, Paris, 2019).24See https://savvy-contemporary.com/en/projects/2017/everything-is-getting-better/. The authors would like to thank Inga Lāce, Maria Lind, Florian Malzacher, Claire Tancons and Vera Zalutskaya for the editorial comments.

- 1Witold Gombrowicz, Diary, trans. Lillian Vallee (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 204.

- 2Maria Janion, Niesamowita Słowiańszczyzna: fantazmaty literatury (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2007).

- 3We use two distinct yet also overlapping terms: “Eastern Europe” as it was drawn during the Cold War and “Central-Eastern Europe,” which marks a smaller space within the East. What is labeled generally as “Eastern Europe” contains three distinct areas: (1) Central-Eastern Europe, which is situated between the Baltic Sea in the north, Germany in the west, and the Danube River in the south; (2) South-Eastern Europe (or the Balkans), which is south of the Danube; and (3) European East, which comprises most of the European part of Russia along with the states situated in the Caucasus and the eastern parts of Ukraine and Belarus. In this essay, for historical reasons, the term “Central-Eastern Europe” takes a predominantly Polonocentric perspective, but it should not be confused with the German notion of Mitteleuropa, whichmarks a smaller space of strong German political, cultural, and economic influence within Central-Eastern Europe.

- 4Ekaterina Degot and David Riff, “Perverse Decolonization,” in Stealing from the West: Pluriversale VII, 20-9–10-12-17, https://www.adkdw.org/downloads/PLU7_BOOKLET_WEB.pdf.

- 5Ibid., 71.

- 6Praktyka Teoretyczna 38, no. 4 (2020), https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/prt/issue/view/1882.

- 7For analyses of mechanisms of racialization, see Livio Boni and Sophie Mendelsohn, La vie psychique du racisme (Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2021).

- 8Zoltán Ginelli, email message to authors, [25 March 2021]. See also https://www.is.uw.edu.pl/en/research-and-conferences/research/echoes.

- 9Immanuel Wallerstein, World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction, Duke University Press, 2004

- 10Timea Junghaus, See also: http://politicalcritique.org/cee/hungary/2017/interview-timea-junghaus-budapest-international-centre-roma-culture-berlin-eriac-decolonization/

- 11Nidhi Trehan and Angela Kocze, “Racism, (neo-)colonialism and social justice: the struggle for the soul of the Romani movement in post-socialist Europe,” in Racism Postcolonialism Europe, eds.Graham Huggan and Ian Law (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), 50–74, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300584669_Racism_neo-colonialism_and_social_justice_the_struggle_for_the_soul_of_the_Romani_movement_in_post-socialist_Europe.

- 12Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, See also: https://eriac.org/my-feminism-does-not-shout-but-it-tells-stories-malgorzata-mirga-tas-and-edis-galushi-in-conversation-with-joanna-warsza/

- 13Ibid.

- 14Ethel C. Brooks, See also: The Possibilities of Romani Feminism, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/665947

- 15Margaret Tali, “Remembering and Re-imagining Histories to Repair, BLOK, posted December 24, 2020, http://blokmagazine.com/remembering-and-re-imagining-histories-to-repair/.

- 16Ibid.

- 17For more, see Joanna Warsza and Jan Sowa, eds., Everything Is Getting Better, exhibition reader. (Berlin: SAVVY Contemporary, 2017).

- 18Olga Stanisławska, “After ‘Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, Raj, (Paradise), 2012,’” posted March 2020, https://obieg.pl/en/172-emma-wolukau-wanambwa-paradise-2012.

- 19Ibid.

- 20Ibid.

- 21See Magda Szcześniak, “Fake it Till You Make it: The Trouble with the Global East Category,” Praktyka Teoretyczna 38, no. 4 (2020), https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/prt/article/view/28150/25458.

- 22See https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=4153124098033927&ref=watch_permalink.

- 23See Liza Premiyak, “Ripoff fashion ruled Eastern Europe’s label-hungry ’90s. Why are designers celebrating it now?,” Calvert Journal, posted March 5, 2020, https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/11671/knock-off-fashion-eastern-europe-national-identity.

- 24See https://savvy-contemporary.com/en/projects/2017/everything-is-getting-better/.