Magdalene A. N. Odundo is a ceramic artist born in Kenya in 1950 but residing in Britain since 1971. Much has been made of her biography and the complexities of her education, training, and rigorous practice of creating beautiful vessels that speak to multiple associations and inspirations across the history of art and their resonances with the human form, especially the bodies of women. Odundo, who has been contextualized as a British studio potter and an artist of African descent, belonging to a millennia-old heritage of women’s pottery-making, transcends the restrictions of this duality, working in clay as well as in other mediums, including graphite, bronze, photo transfer, and glass.

Magdalene Odundo has received critical acclaim from writers on the three continents where her remarkable vessels have been exhibited and collected. The praise often begins with the unforgettable impact of first experiencing them: their sensuous and commanding presence as sculpture and their mystique in terms of how Odundo created them.

There has been equally probing curiosity about the ideas and sources that inspired their iconic forms, which seem familiar and new at the same time. Their evocative power resides in Odundo’s deliberate references to pottery made in Africa and, simultaneously, her comprehensive knowledge of the world’s ceramic history. There is an impressive eloquence in the responses to Odundo’s work, among them, those of curator Yvonne G. J. M. Joris, art historian Gert Staal, art critic Louisa Buck, curator Ulysses Grant Dietz, and fashion designer Jonathan Anderson.1Yvonne G. J. M. Joris, ed., Magdalene Odundo, exh. cat. (’s-Hertogenbosch: Museum Het Kruithuis, 1994), 7; Gert Staal, “Silent Dancers,” in ibid., 15–16; Louisa Buck, “Magdalene Odundo discusses dancing with clay ahead of Venice Biennale exhibition,” in TAN (The Art Newspaper), March 28, 2022 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/28/interview-magdalene-odundo; Ulysses Grant Dietz, in Arts of Global Africa: The Newark Museum Collection,ed. Christa Clarke, exh. cat. (Newark: Newark Museum, 2017), 319, cat. 87; and Jonathan Anderson, quoted in Sarah Medford, “Curve Appeal,” Wall Street Journal Magazine, May 2021, 94. When asked by Nigerian writer Ben Okri in a 2019 interview what she wants people to take away with them when they look at her ceramic pots, she replied, “I just want them to be amazed and astonished that this very simple material, which is so cheap, so easily found, which we all walk on, can be transformed”.2Magdalene Odundo, “Roots and Resonances,” interview by Ben Okri, in Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, ed. Andrew Bonacina, exh. cat. (London: InOtherWords, 2019), unpaginated.

Since the earliest exhibitions of her vessels in the 1980s, there has been a focus on documenting the specifics of Odundo’s biography and her complex journey to becoming one of Britain’s most celebrated ceramic artists and one of the first Africa-born contemporary artists to represent Global Africa in museum installations.3Bonacina, The Journey of Things. This preoccupation with her biography has generated a standardized narrative that has been repeated in brief or long form in nearly every exhibition text or published essay, starting in 1994 and continuing to the present.4Among the most comprehensive essays are Emmanuel Cooper, “The Clay of Life: The Ceramic Vessels of Magdalene Odundo,” in Magdalene Odundo, ed. Anthony Slayter-Ralph (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2004), 9–55; Monique Kerman, Contemporary British Artists of African Descent and the Unburdening of a Generation (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 23–56; Elsbeth Joyce Court, “Magdalene A. N. Odundo: Pathways to Path Maker,” Critical Interventions: Journal of African Art History and Visual Culture 11, no. 1 (2017): 77–104, https://doi.org/10.1080/19301944.2017.1320887; Bonacina, The Journey of Things; and Marla Berns, Ceramic Gestures: New Work by Magdalene Odundo, exh. cat. (Santa Barbara: University Art Museum, University of California, 1995). Indeed, it has tended to inhibit how people write about her work, limiting fresh conceptual or critical insights, and increasing a reliance on Odundo’s own words. The consistency of her vessel types and the very knowledge that, with them, Odundo is releasing clay’s captive voices has writers seeking to describe and expose what the work is saying and why. Curators, artists, and scholars have conducted interviews with her, and her responses are extensively quoted.5See the impact of Odundo’s words in Berns, Ceramic Gestures; Cooper, “The Clay of Life”; and Augustus Casely-Hayford, “Magdalene Odundo: Breath and Dust,” in Resonance and Inspiration: New Works by Magdalene Odundo (Gainesville: Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, 2006), 13–15.

For Odundo, the human body is a vessel, and her creations share its language: bodies, necks, mouths, lips, and other defining essentials like nipples, umbilici, and vertebrae. These anthropomorphic alignments are universal in global ceramics, and yet the way Odundo abstracts and synthesizes them has been a hallmark of her achievement—and is especially visible in Untitled #15 (1994; fig. 4).

Odundo draws from a storehouse of images and memories, often looking for the essential bits in both to create her vessel types. The striking form of Untitled #10 (1995; fig. 5), for example, captures in clay the extraordinary backward sweep of headdresses worn by early twentieth-century Mangbetu women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Newark Museum, Purchase 1996, Louis Bamberger Bequest Fund. Image courtesy The Newark Museum.

She incorporated into her formal college studies what she had learned from her African teachers, especially while in residence at the Pottery Training Centre in Abuja, Nigeria, which was established in the early 1950s by British ceramist Michael Cardew (1901–1983), who was himself a student of British studio potter Bernard Leach (1887–1979). By the time she earned her MA in 1982 at the Royal College of Art, Odundo had distilled her own style and technique of working as a 1983 example in the British Museum collection illustrates (fig. 6).

Indeed, based on her experience with local Gbari potters in Abuja, Odundo developed a method of hand-building and coiling and a process of finishing her leather-hard vessels with a labor-intensive sequence of burnishing, applying slip, and lightly re-burnishing to achieve a high-luster surface when fired. She especially admires the celebrated Gbari artist Ladi Kwali (1925–1984), who became her mentor.6Ladi Kwali’s face appears on Nigerian currency, an indication of her fame. In 2015, Odundo curated an exhibition of Kwali’s work. See Bonacina, The Journey of Things, caption 5. Kwali had joined Cardew in 1954 and integrated the wheel throwing, gas-kiln firing, and shiny glazing that he had introduced, none indigenous to the region or, for that matter, to most of sub-Saharan Africa. Kwali was an influential teacher, as were others at the Pottery Training Centre, and key to what Odundo learned from them was the importance of tenacity, patience, and humility.7In addition to Ladi Kwali, her Gbari teachers included Asibi Aidoo, Lami Toto, and Kainde Ushafa. See Berns, Ceramic Gestures, 3.

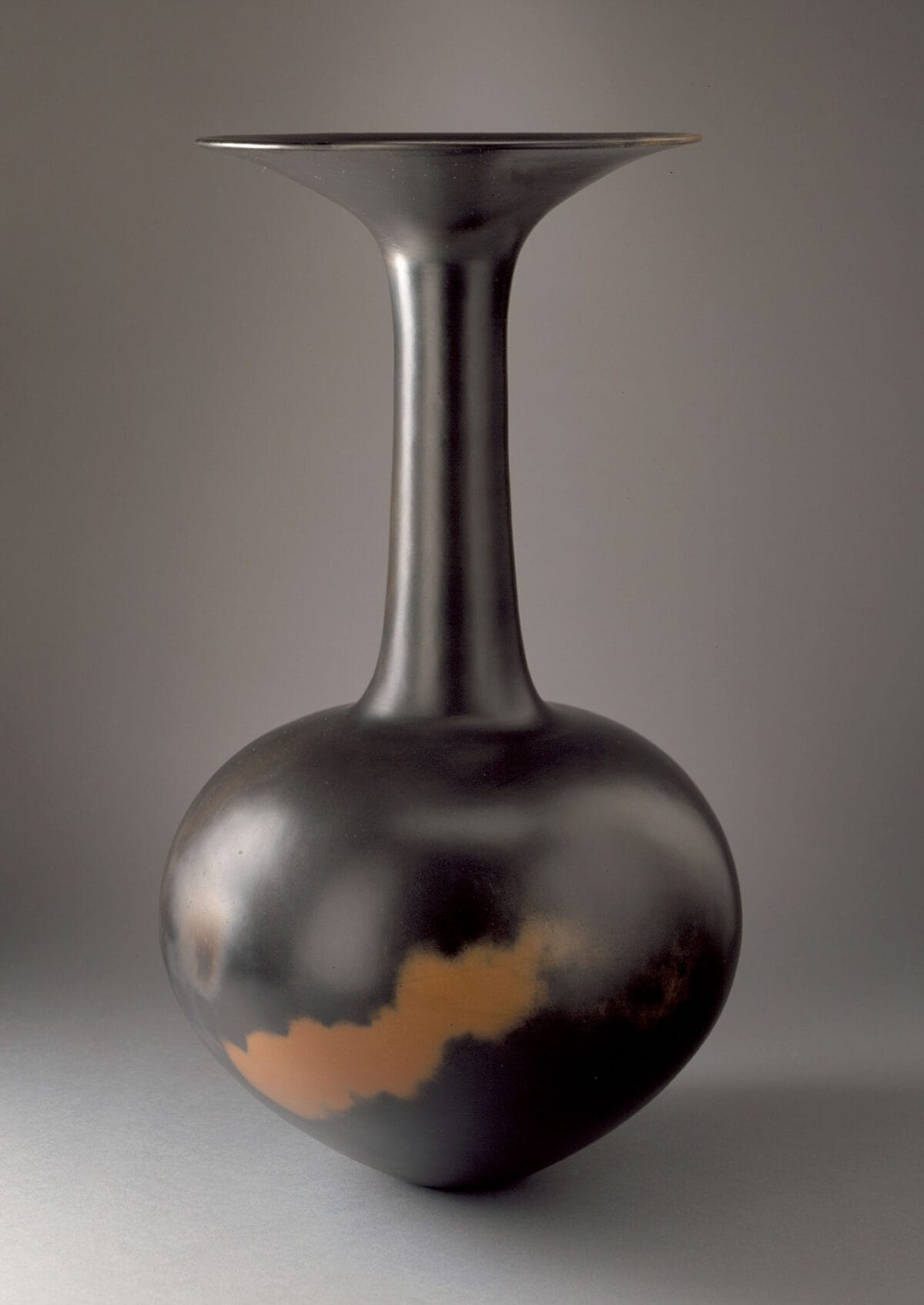

Odundo spends weeks or even months meticulously building her sculptures. She repeats the shapes she favors (and yet they are never identical), such as that of Newark’s Untitled #10 (fig. 5), as part of an inexhaustible quest to achieve “perfect symmetry and perfect harmony.”8Odundo, interview with author, 1994; see also Susan Mullin Vogel, ed., Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art (New York: Center for African Art; Munich: Prestel, 1991), 21. The control intrinsic to her hand-building process is then tested by the firing, first in a purely oxidizing atmosphere that turns them a bright red-orange that intensifies the elegance and fluidity of their shapes, as is expressed in Untitled #4 (1995; fig. 7).

Then, if she chooses, she fires her creations again (and again) in an oxygen-poor environment that changes “the static orange to the one you cannot predict with its various shades of black.” The Munich Design Museum’s Kigango cha Baba and Kigango cha Mama (2009; fig. 8) show how the firing conditions yield variations in patterns of flashing and areas of smoky iridescence that can be dazzling and are the outcome of the inevitable surprises teased by chance in the kiln.

Their humanity is a part of the tension Odundo negotiates between stasis and movement as the vessels undergo the alchemy of transformation. She uses the expressiveness of her vessels’ necks and flaring mouths and the treasured “spots” from the firing to impart a sense of vitality, which is dramatically evident in Untitled #11 (1995; fig. 9) and Untitled (1994; fig. 10). Success for Odundo is having the vessels “dance” even though they are standing still.9Berns, Ceramic Gestures, 23.

Indeed, part of the innovation of her 2019 retrospective exhibition, Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, organized by former chief curator Andrew Bonacina for the Hepworth Wakefield museum, was inviting Odundo to help curate the selection, rendering the specificity of “things” she has identified as her “contemporary and ancient heroes” visible. The project took as its subject the links between what Odundo has studied and revered and the formation of her own ceramic vocabulary. While these links have been detailed in publications and exhibition catalogues, the idea of bringing them together physically in the exhibition space was introduced in the 2006 exhibition Resonance and Inspiration at the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida. Transcending geographical, temporal, and categorial boundaries, the more than seventy-five disparate objects in The Journey of Things were juxtaposed by the artist with about fifty of her own ceramic vessels dating from 1974/76 to 2016, making for incomparably evocative and astonishing experiences, which she has long sought in the reception of her work.

The range of suggested affinities between her work and the global sources she has mined is impressive. It brings Odundo’s comparative approach into sharp focus, and is exemplified in the installation view provided here (fig. 11).10A parallel exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum at the University of Cambridge in 2021 narrowed the focus to the works that stood out for the artist when she arrived in Cambridge in 1971 and was mesmerized by the glories of the city’s collections. Odundo has chosen her sensuous oxidized vessel from the British Museum (Untitled, 1994; see fig. 9), because for her, it animates the static aspects of fired clay: it conjures the image of Dame Margot Fonteyn (1919–1991), with her long neck and graceful arms, dancing in Swan Lake.

Surrounding it are three works by artists Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915) as well as a Greek amphora with black-painted decoration by an “unknown maker.” The subjects of all five works are engaged in activity, whether dancing, wrestling, or frolicking. There is an implied parity among them. Yet, does an arrangement like this complicate viewers’ expectations of Odundo’s influences, pushing the reception of her work beyond the as yet intractable dichotomy between fine arts and craft, suggesting they are all in fact “art”? Or does the journey of things imply something else? The exhibition organizers seem to erode the conceptual ambition of Odundo’s approach with labels and catalogue captions that name “known” artists and call others “unknown makers,” as if their anonymity in the historical record denies them status as artists.11The discursive captions in the catalogue accompanying Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things provide information on the seventy-eight global works selected for the exhibition. In them, named artists are situated historically or associated with source material. The many objects for whom specific makers are “unknown” or “unrecorded” are linked to the cultural contexts in which they originally had meaning. Calling them “makers” instead of “artists” exposes the bias of western categorizations and hierarchies, and the persistent quandary of admitting global creative production into the canon of fine art.

The Journey of Things, which toured to the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, along with the artist’s participation in several recent international group and monographic shows—including the 2022 Venice Biennale curated by Cecilia Alemani—have further sealed her reputation and the recognition she so clearly deserves as an accomplished international artist. Through them, Odundo has eclipsed the restrictions of her identity bifurcation and is celebrated on her own terms: for her lifelong dedication to the vessel form and to fired clay as her preeminent mode of expression.12Buck, “Magdalene Odundo discusses dancing with clay ahead of Venice Biennale exhibition,” Art Newspaper, March 28, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/28/interview-magdalene-odundo The five vessels, made between 2009 and 2017 and elegantly displayed in the Corderie dell’Arsenale in Venice (fig. 12), represent several of her iconic styles and her tendency to work in series in which each constituent creation is unique. With the exception of the central vessel from the Asymmetrical series, the vessels show the variety within the Symmetrical series. Together, the grouping underscores Odundo’s technical and artistic virtuosity and the impact of her subtle humanizing details.

These recent curatorial projects, along with a long list of residencies, including collaborations with Sloss Metal Arts in Alabama in 1993, the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum for the 2002 project Acknowledged Sources,13Details on this highly autobiographical 2002 project are included in Simon Olding, “Magdalene Odundo: Ceramics and Curatorship,” in Slayter-Ralph, Magdalene Odundo, 75–85. and with glass artists at Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle, the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, and the National Glass Centre at the University of Sunderland (2012–14) encapsulate the persistent spirit of discovery and experimentation that drives her ambitions. At the National Glass Centre, for instance, she produced a collaborative three-part project called Tri-part-it-us. Its culmination was the 2014 installation with one thousand suspended blown-glass elements called Transition II (fig. 13).14See Martina Margetts, “The One and the Many,” in Magdalene Odundo: Tri-part-it-us, exh. cat. (Sunderland: Art Editions North, University of Sunderland in conjunction with Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, National Glass Centre, and CIRCA projects, 2015); see also Court, “Pathways to Path Maker,” 97–100. Its spectacle contrasts with the single 3500-year-old tiny glass ear stud from ancient Egypt that Odundo used as the catalyst for the residency.15Odundo sourced this Egyptian ear stud from the ethnographic collection of London’s Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London; see Margetts, “The One and the Many,” 6. The closeness of the ear stud to the body, in that the two become one when the stud is worn, continued Odundo’s exploration of art’s humanity and her fascination with glass as an artistic medium.

Throughout her career, Magdalene Odundo has resisted a singular classification. Because she was educated in Britain, which has been her home base since 1971, she is seen there as a British studio potter and considered one of its best postwar ceramists. In the United States, she was included in the groundbreaking and controversial 1991 exhibition Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, in which she was one of only two Africa-born women artists and the only ceramist selected by its curator, Susan Vogel. Odundo’s work was a revelation to many of us who had studied the arts of Africa in the 1970s and 1980s and done research on living artists working in “traditional styles” (including the women who still made pottery in their home communities). What distinguishes Odundo from other African artists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries is her “unapologetic attitude to the idea of beauty.”16Edward Lucie-Smith on Magdalene Odundo, “East Meets West” in A Dialogue in Clay (Prestbury, Cheshire: Artizana, 1999), 18. See also Berns, Ceramic Gestures, 1. This has helped her overcome the emphasis on the “Africanness” of her work and instead drawn attention to its formal innovation and distinction from African village–based domestic and ritual pottery.

As a woman who works primarily with clay, Odundo has been marginalized and described as a “maker” or “potter” outside the mainstream definition of fine art per the western canon. This distancing also seems to have minimized her participation in the political discourses around race, gender, and blackness. Monique Kerman has argued that Odundo came of age as a professional before the debates concerning black British art and artists gained momentum, and thus did not engage overtly with issues of racial and ethnic difference.17Kerman, Contemporary British Artists, 19. She was excluded from many survey exhibitions that made stars of other contemporary British artists of African descent, like Chris Ofili (born 1968), Steve McQueen (born 1969), and Yinka Shonibare (born 1962).18Kerman, Contemporary British Artists, 230. Yet, by the late 1990s, Odundo’s vessels had become better recognized in the United States and in the United Kingdom, and work like hers—long typecast as craft or design—had begun to appear in the permanent collection galleries of art museums. Her sleek modernist sculptural forms offered curators of African art a comfortable bridge between historical traditions and the global contemporary. Odundo’s vessels appeared as the first and sometimes only ambassadors of the new. In the newly reopened de Young Museum in San Francisco, for example, their Odundo vase (2007; fig. 14) was mounted in a case with six historical African wares. Her vessels were also paired with shimmering hangings by El Anatsui (born 1944)—which had received international notoriety at the 2007 Venice Biennale—and installed in museums and galleries, further emphasizing the excitement of original work by contemporary Africa-born artists.19Some examples include the Sainsbury Africa Galleries, which opened in 2001 at the British Museum in London (see Court, “Pathways to Path Maker.,” 92–94). In the 2006 permanent collection exhibition at the Fowler Museum at UCLA, Intersections: World Arts, Local Lives, the thematic section “Tradition as Innovation” featured an Odundo vessel and an El Anatsui hanging alongside other global works.

Over the same arc of her career, she has been dedicated to education as a university teacher, researcher, supervisor, and visiting lecturer; as a mentor encouraging students and young aspiring artists, especially those from Africa, to take up ceramics as a profession; and as an external examiner for various national and international universities. In recognition of her commitment to education and the field of ceramics, Odundo was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List for Services to the Arts in 2008, honored in 2018 with the ceremonial leadership appointment as Chancellor of the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, Surrey (where she taught for seventeen years), and elevated to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours List in 2020 for Services to Arts and Arts Education. Even if her shifting identity remains a conundrum and the art-versus-craft debate has yet to be dismantled, the rigor of Odundo’s process, her restless search for perfection, and her receptivity to new sources and mediums of inspiration and collaboration have won her significant acclaim as a contemporary international artist with an abiding love of clay.

- 1Yvonne G. J. M. Joris, ed., Magdalene Odundo, exh. cat. (’s-Hertogenbosch: Museum Het Kruithuis, 1994), 7; Gert Staal, “Silent Dancers,” in ibid., 15–16; Louisa Buck, “Magdalene Odundo discusses dancing with clay ahead of Venice Biennale exhibition,” in TAN (The Art Newspaper), March 28, 2022 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/28/interview-magdalene-odundo; Ulysses Grant Dietz, in Arts of Global Africa: The Newark Museum Collection,ed. Christa Clarke, exh. cat. (Newark: Newark Museum, 2017), 319, cat. 87; and Jonathan Anderson, quoted in Sarah Medford, “Curve Appeal,” Wall Street Journal Magazine, May 2021, 94.

- 2Magdalene Odundo, “Roots and Resonances,” interview by Ben Okri, in Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, ed. Andrew Bonacina, exh. cat. (London: InOtherWords, 2019), unpaginated.

- 3Bonacina, The Journey of Things.

- 4Among the most comprehensive essays are Emmanuel Cooper, “The Clay of Life: The Ceramic Vessels of Magdalene Odundo,” in Magdalene Odundo, ed. Anthony Slayter-Ralph (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2004), 9–55; Monique Kerman, Contemporary British Artists of African Descent and the Unburdening of a Generation (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 23–56; Elsbeth Joyce Court, “Magdalene A. N. Odundo: Pathways to Path Maker,” Critical Interventions: Journal of African Art History and Visual Culture 11, no. 1 (2017): 77–104, https://doi.org/10.1080/19301944.2017.1320887; Bonacina, The Journey of Things; and Marla Berns, Ceramic Gestures: New Work by Magdalene Odundo, exh. cat. (Santa Barbara: University Art Museum, University of California, 1995).

- 5See the impact of Odundo’s words in Berns, Ceramic Gestures; Cooper, “The Clay of Life”; and Augustus Casely-Hayford, “Magdalene Odundo: Breath and Dust,” in Resonance and Inspiration: New Works by Magdalene Odundo (Gainesville: Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, 2006), 13–15.

- 6Ladi Kwali’s face appears on Nigerian currency, an indication of her fame. In 2015, Odundo curated an exhibition of Kwali’s work. See Bonacina, The Journey of Things, caption 5.

- 7In addition to Ladi Kwali, her Gbari teachers included Asibi Aidoo, Lami Toto, and Kainde Ushafa. See Berns, Ceramic Gestures, 3.

- 8Odundo, interview with author, 1994; see also Susan Mullin Vogel, ed., Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art (New York: Center for African Art; Munich: Prestel, 1991), 21.

- 9Berns, Ceramic Gestures, 23.

- 10A parallel exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum at the University of Cambridge in 2021 narrowed the focus to the works that stood out for the artist when she arrived in Cambridge in 1971 and was mesmerized by the glories of the city’s collections.

- 11The discursive captions in the catalogue accompanying Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things provide information on the seventy-eight global works selected for the exhibition. In them, named artists are situated historically or associated with source material. The many objects for whom specific makers are “unknown” or “unrecorded” are linked to the cultural contexts in which they originally had meaning. Calling them “makers” instead of “artists” exposes the bias of western categorizations and hierarchies, and the persistent quandary of admitting global creative production into the canon of fine art.

- 12Buck, “Magdalene Odundo discusses dancing with clay ahead of Venice Biennale exhibition,” Art Newspaper, March 28, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/28/interview-magdalene-odundo

- 13Details on this highly autobiographical 2002 project are included in Simon Olding, “Magdalene Odundo: Ceramics and Curatorship,” in Slayter-Ralph, Magdalene Odundo, 75–85.

- 14See Martina Margetts, “The One and the Many,” in Magdalene Odundo: Tri-part-it-us, exh. cat. (Sunderland: Art Editions North, University of Sunderland in conjunction with Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, National Glass Centre, and CIRCA projects, 2015); see also Court, “Pathways to Path Maker,” 97–100.

- 15Odundo sourced this Egyptian ear stud from the ethnographic collection of London’s Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London; see Margetts, “The One and the Many,” 6.

- 16Edward Lucie-Smith on Magdalene Odundo, “East Meets West” in A Dialogue in Clay (Prestbury, Cheshire: Artizana, 1999), 18. See also Berns, Ceramic Gestures, 1.

- 17Kerman, Contemporary British Artists, 19.

- 18Kerman, Contemporary British Artists, 230.

- 19Some examples include the Sainsbury Africa Galleries, which opened in 2001 at the British Museum in London (see Court, “Pathways to Path Maker.,” 92–94). In the 2006 permanent collection exhibition at the Fowler Museum at UCLA, Intersections: World Arts, Local Lives, the thematic section “Tradition as Innovation” featured an Odundo vessel and an El Anatsui hanging alongside other global works.