This year’s C-MAP seminar series, Transversal Orientations, comprised four panels, took place on Zoom in June 2021. Textual responses to each of the panels were commissioned to further discussion about the seminar’s central concerns. In this essay, Dr. Hlonipha Mokoena (Associate Professor at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research) provides a profound reflection and evocative epilogue to Entangled Terrains, the third panel in the seminar series featuring curator and educator Sandra Benites, Black Athena Collective (artists Heba Y. Amin and Dawit L. Petros) and scholar Chie Ikeya.

This text is also available in Portuguese here.

When Noni Jabavu published The Ochre People in 1963, she was referring to the dismissive definition of non-Christian Africans as those “daubed in red ochre” (amaqaba).1Noni Jabavu, The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life (London: John Murray, 1963), 61-62. Even back then, the debates between converted Africans and their non-Christian cousins revolved around the skin and the body. Little did Jabavu know that in a future century and in the decades to come, “the ochre people” would reappear to remind us of the price that has been paid for our “civilization.” The earth—from which the ochre comes—has been ripped, torn, burnt, scarred, and desecrated, and the ochre people are the only ones who seem to understand the incomputable loss. Without seeking to simplify the connection between South Africa and Brazil, it is compelling to imagine that the Xhosa of South Africa and the Guaraní people of Brazil chose red ochre because it is the color of plenitude, it is the color that is your skin but is not your skin, it is the color of the rivulets of water that run deep into the earth after a rainstorm, it is the color of blood. In Western chromatology, red is the color of danger and so we are warned off its sustenance, its life-giving force, and led to imagine its opposite: life-taking. The sanguine metaphors could also be extended to the Library of Alexandria since this library was situated in a littoral and oceanic matrix consisting of several lakes and the Mediterranean Sea. One can only imagine the ebb and flow of color as various rivers flowed into the sea. To the east of Alexandria, the Nile River would be depositing its black waters, its sediments, into the sea, and it too would have reminded the viewer of the life-giving force of the river’s deposits. Ochre, earth, silt, and sediment—these are the tones with which the red ochre people are all too familiar: ochre and clay as living and vital life forces rather than as just matter.

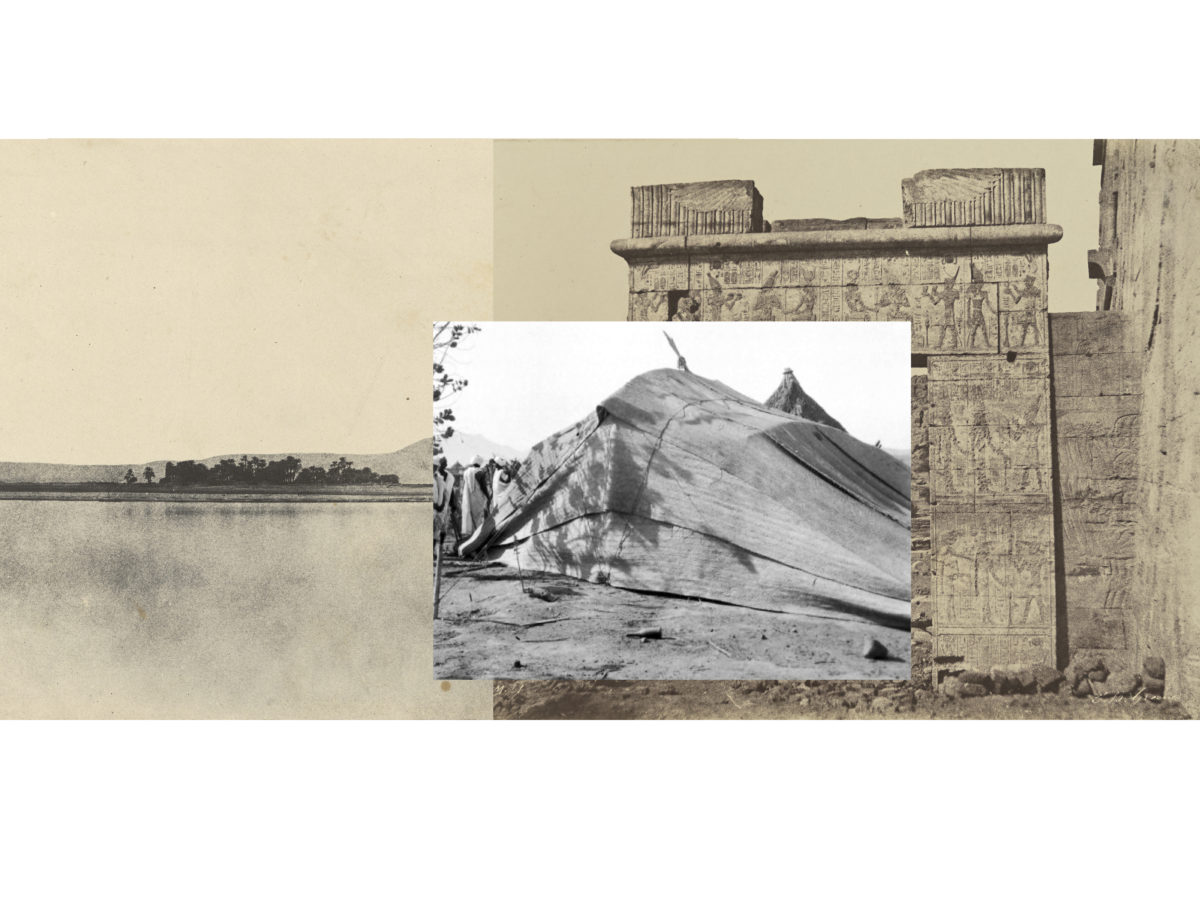

There seems to be little reason to believe that thinking through the vivifying forces of ochre, sand, and clay does not also lead us into the world of intimacies that was partly possible through sea voyages. In the same way that the ancient Egyptians were seafaring and traveled far south to collect tribute, there are plenty of reasons to conclude that such travels were also driven by intimate relationships. Thus, is it possible to argue that what unifies Sandra Benites, the Black Athena Collective, and Chie Ikeya are that they all are thinking about worlds and lives that were made and unmade by travel—by foot and by sea. In the same way that the Guaraní term “oguata” defines life by walking, the tent defines life by the planting and uprooting of habitat. The transmigration implied in these acts confirms the human need to expand one’s vistas, to stretch one’s horizons. But these are also cultural claims; they are commitments to a peripatetic existence that shuns the monumental dwelling, or perhaps even flees the security of the casbah, the fortress. If the logics of walking and “camping” defy our modern sensibilities, it is only because we have so little faith in the past and its denizens. We have placed so much faith in the idea that travel means speed, that it means the saving of time, that we have lost our ability to imagine that travel may mean the creation of time, the assembling and disassembling of the cosmos, and the conversion of time into a compact and portable cultural artifact. All this footing and tenting occurs as the earth rises to meet us—red, black, sand, clay. The ochre people would know that there is no travel without a pebble in one’s shoe.

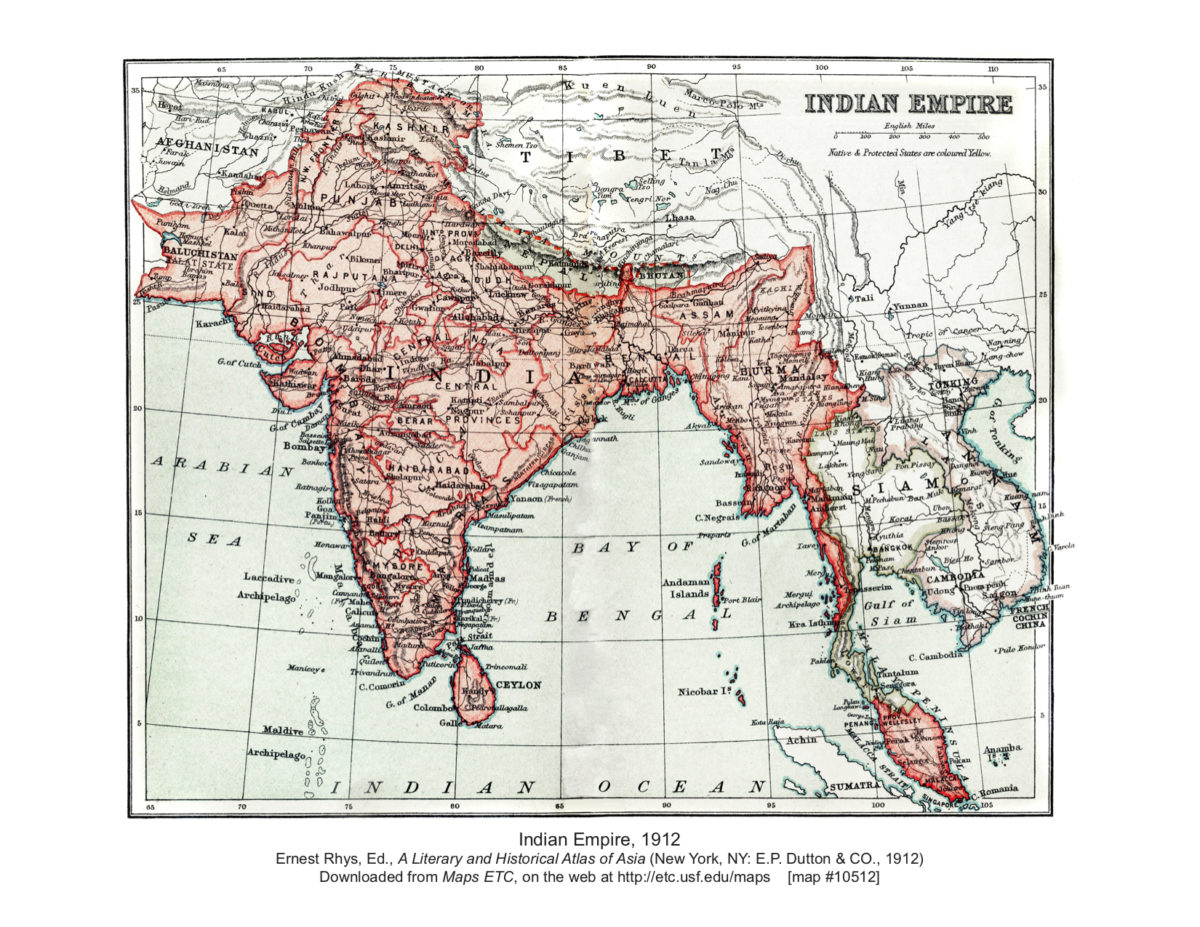

The crisscrossing ways in which love, desire, family, and affect travel across spatial boundaries is so eloquently present in Chie Ikeya that it is worth repeating her observations that the standard “area studies” of Asian migrations and mobility have traditionally placed men (or the bodies of men) as the prime movers and shapers of inter-Asian mobilities—“men are portrayed as circulating across oceans and continents sowing seeds and spinning webs of exchange, debt, patronage, pilgrimage, lineage, and kinship, while women are relegated to the role of repository and reproducer, domesticating and nourishing what have been sown, spun, and propagated by men.”2Chie Ikeya, “Interasian Intimacy & Imperial Formation: The Story of Ngwe Bwint, Rahim Rasool, and Ngwe Ya,” abstract (unpublished paper June 9 2021), typescript. The relegation of women to mundane or maternal roles and functions has meant that regardless of how wide the world of “Asia” proves to be, the lives of women are always limited to the contingencies of the local. The exclusion of women’s mobility contradicts many of Benites’s observations about the meaning of travel and the ways in which it makes a human. The paternalistic reading of history, in which the only relevant women are the “mothers of the nation,” hems in and curtails our understanding of how the world is not just made in the womb. As in other colonial outposts, we know these “offending” women because they have appeared in court as plaintiffs or defendants. The adversarial nature of legal disputation means that even before you know the story, you know that someone will be found “guilty,” that someone will be told that his or her actions, or non-actions, are a contravention. But, as in other colonies, women were almost always the ones being disinherited or chastised. Again, here, the courts of law functioned on the assumption that only the “native woman” is local—that her body must and should remain intact while the man’s body traverses boundaries. The hysteria that follows from this is the “nationalist” impulse to declare the body of the “native woman” as endangered, as porous, and as vulnerable to “exotic” penetration and invasion. It is this selective reasoning that unites the colonial judicial system and the local patriarchs and “protectors of women”—the “native woman” must remain inert.

The “Black Athena” has become an icon of the opposite of the confined woman. Martin Bernal’s paradigm-shifting volumes have made it possible for us to at least imagine that the goddesses of the ancient world were of African and Eastern origin.3Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, vols. i and ii (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987). In Bernal’s reimagining of antiquity, the “founding fathers” of Greek ideas—Plato, Aristotle, Aeschylus, Herodotus—were the acolytes of the Afroasiatic world. This term—“Afroasiatic”—already re-maps the globe and forces us to affirm that ideas and people have always traveled, and that no culture or civilization has a claim to primacy. Essentialist thinking about the singular or unilinear origins of culture and civilization is therefore not sustainable once the lessons of the “Black Athena” are absorbed. It is no accident that the book was met with mixed reactions from classical scholars—some welcomed the revivification of the ancient world’s relationship with Africa, while others were protective of the assumption that “classics” equals “Western.”4Lefkowitz, Mary. “The Afrocentric Interpretation of Western History: Lefkowitz Replies to Bernal.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 12 (1996): 88-91. Accessed July 6, 2021. doi:10.2307/2962996. By naming their collective after this cause célèbre, Heba Y. Amin and Dawit L. Petros are extending the Bernal thesis and counter narrative to novel applications. In their work and thinking, not only has Africa been central to the ignition of the world’s intellectual fire, but the vanished Library of Alexandria is the lightning rod by which we can measure the volatility and boom of a reimagined “Afroasiatic” worldview. “Black Athena” therefore doesn’t just stand for the repositioning of Egypt in relation to the Mediterranean, it also stands for the repositioning of the nomadic nature of knowledge and the ways in which, as the jeli (griot) of The Epic of Son-Jara states, “That which sitting will not solve / Travel will resolve.”5John William Johnson, Fa-Digi Sisòkò, Charles S. Bird, et al., The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), 87. By making the Alexandrian library the focal point of meditations on the peripatetic nature of knowledge and artistic production, the Black Athena Collective revives not just Martin Bernal’s arguments, but also many other Afrocentric / Afropolitan ideas that define African culture as the product of the traveler, the adventurer, the seeker, the exile, and the pilgrim. In these ways, the tent becomes the cosmos because it is the place where cosmic as well as cosmopolitan imaginings can take shelter. The explosive nature of wisdom acquired through taking the many roads less traveled is evidenced in many legends and stories from Makeda to Mansa Musa. Simply put, one could even go as far as to state that what we know as “Africa” is just another word for boundless wandering—mental, spiritual, and corporeal.

To revert then to Jabavu’s book and the red ochre people. As a young woman who returned to a South Africa she had left at thirteen, Jabavu wrote nostalgically about the sounds and places of her childhood; but what sets her book apart is the fact that her return also marks her birth as a travel writer. The circuit of routes that took her from her home to London returned a seasoned wayfarer who by rail, car, and bus observed her country of birth with a cool, engaged, and critical eye. Although her biography is yet to be written, she exemplifies the cultural embodiment of what happens when an African woman, specifically, becomes a traveler and chronicler. Her book’s title is thus a heartfelt summation of her nostalgia but also an assertion of the intimate bond between her and “the red ochre people” that distance did not extinguish. Thus, in her book, one finds the solace and consolation that no matter how entangled the journeys, the roads always lead back to a “home,” even if it is a vexed one.

- 1Noni Jabavu, The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life (London: John Murray, 1963), 61-62.

- 2Chie Ikeya, “Interasian Intimacy & Imperial Formation: The Story of Ngwe Bwint, Rahim Rasool, and Ngwe Ya,” abstract (unpublished paper June 9 2021), typescript.

- 3Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, vols. i and ii (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987).

- 4Lefkowitz, Mary. “The Afrocentric Interpretation of Western History: Lefkowitz Replies to Bernal.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 12 (1996): 88-91. Accessed July 6, 2021. doi:10.2307/2962996.

- 5John William Johnson, Fa-Digi Sisòkò, Charles S. Bird, et al., The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), 87.