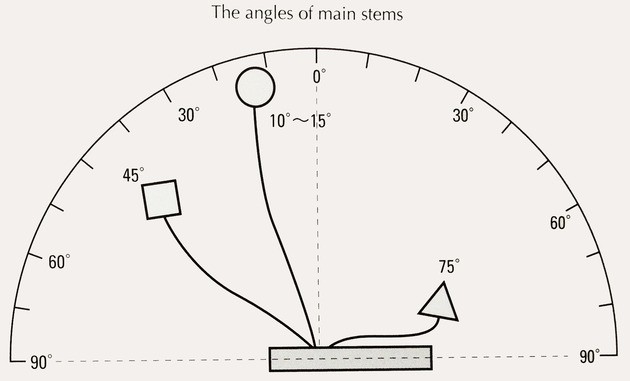

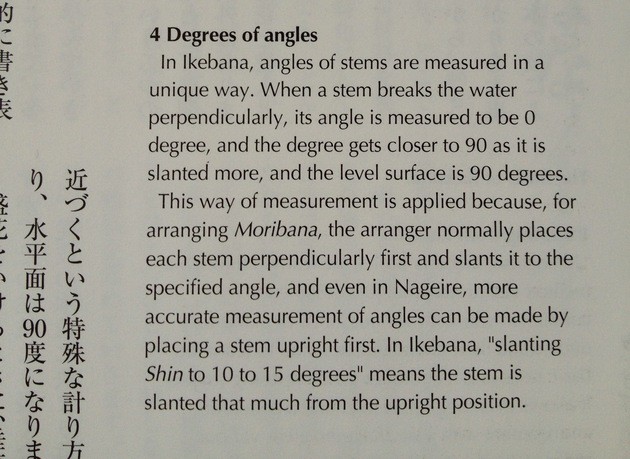

When a stem breaks the water perpendicularly, its angle is measured to be 0 degree, and the degree gets closer to 90 as it is slanted more, and the level surface is 90 degrees.

[from the Sogetsu ikebana handbook]

Silence is not acoustic. It is a change of mind, a turning around.

[John Cage]

Arranging flowers takes place in silence.

Arranging flowers in Sogetsu ikebana, founded in 1927 by Sofu Teshigahara and considered the most experimental of all schools of the traditional Japanese art of flower composition, is no different in this respect.

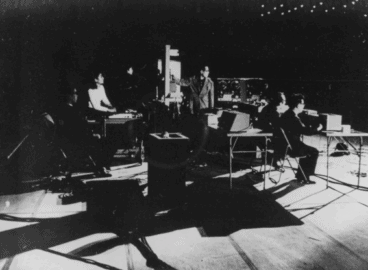

There might have been a visible – or rather, audible – difference in the 1960s, however. Then, while the ikebana students were gathered in their classrooms, diligently and noiselessly following the centuries-old guidelines for the proper alignment of stems with leaves and buds, other young Japanese just three floors below them were vigorously attempting to break every rule of composition: this time, musical.

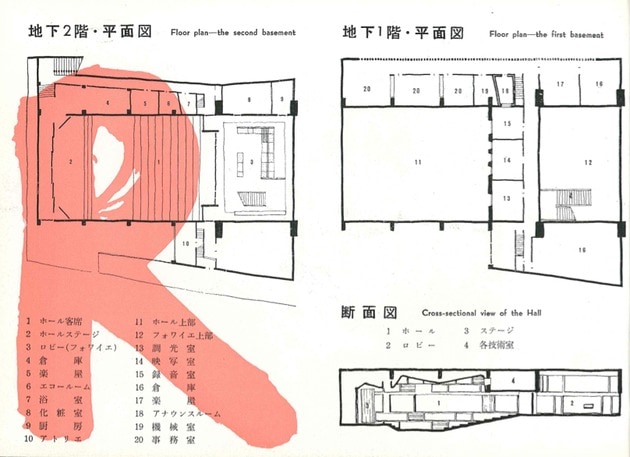

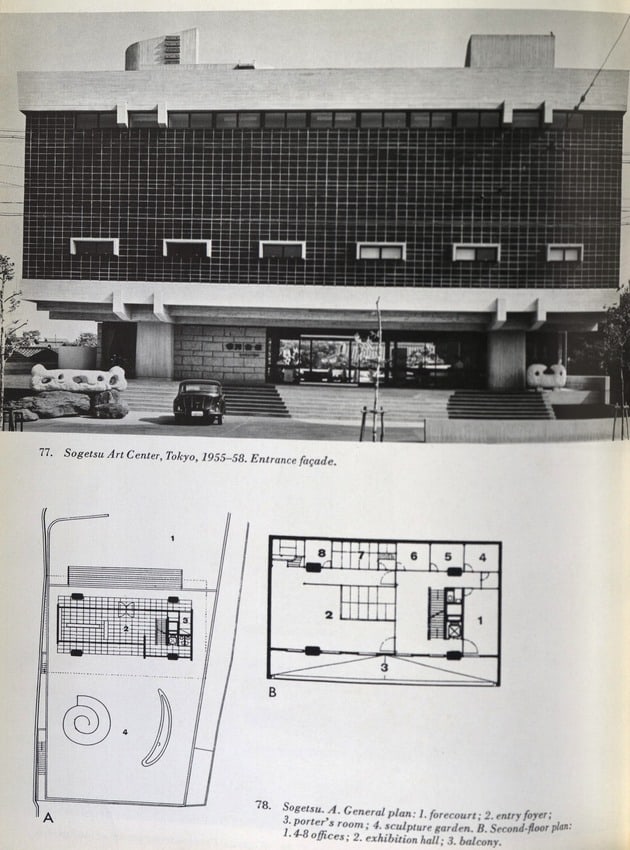

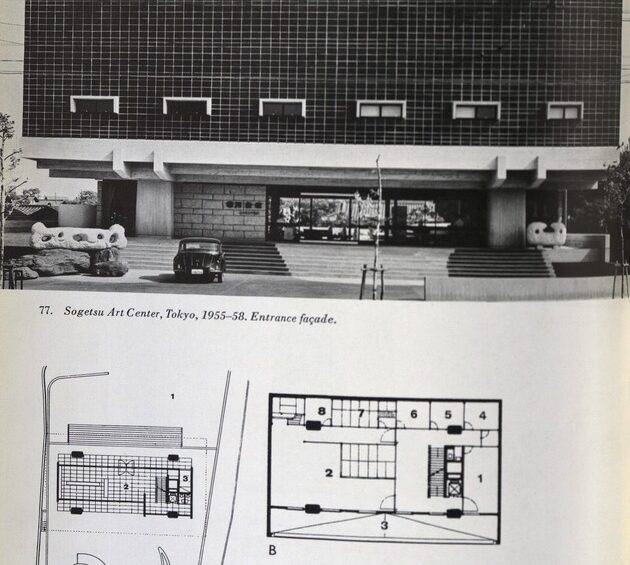

The Sogetsu Ikebana building, a gem of modernist architecture designed by Kenzo Tange, was completed in 1957 and now, sadly, no longer exists. It was comprised of two complementary but very different sets of spaces. The three floors that rose above ground housed the school’s offices and classrooms, while underground lay a vast auditorium and concert hall. It was in the latter that events and concerts of the Sogetsu Art Center, the school’s sister institution founded by Sofu’s son, Hiroshi, took place.

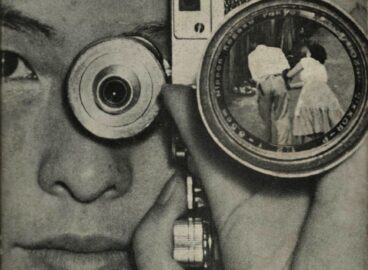

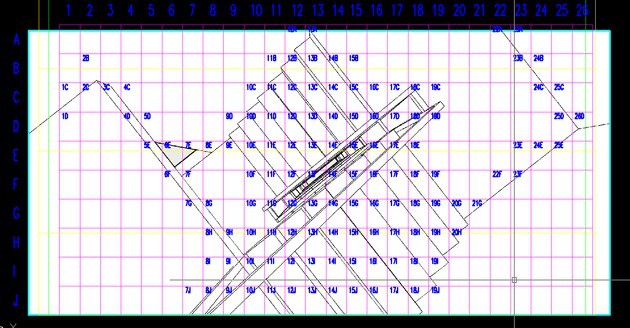

The seemingly irreconcilable tension between these two spaces is the subject of this project by Katarzyna Krakowiak, who investigates the inconspicuous relationships between sound and architecture. The artist is fascinated by how the noiselessness of the school’s upper rooms, where noble women (ikebana was originally a leisure activity for the wealthy) spent hours contemplating the forms of roots and petals, must have been contaminated by echos of sound produced by the experimental musicians working below. The contrast between their exuberant noise-making and the aura of silence and reticence, handed down by generations of ikebana practitioners, triggers imagination. Krakowiak probes this tension in two visual models that she designed on the basis of archival photographs of the building, now destroyed.

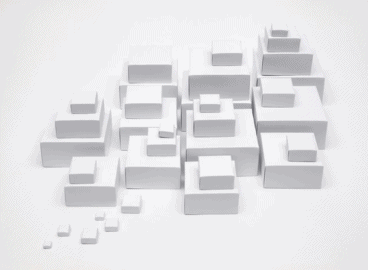

In one model, she imagines the reverberations of sounds produced during concerts entering the upper rooms of the Ikebana school in the form of multicolored spheres. The shapes are dispersed from the stage, where the music was produced, and travel toward the back of the auditorium, bouncing against the walls, with a few penetrating the staircase. In the second model, Krakowiak takes us on a soundless journey through the modernist building’s empty spaces, following the path of the reverberations. Performing a Gordon Matta-Clark-like gesture in her digital visualization, she cuts a hole through all the floors, down to the ground, allowing the ikebana and the concert hall spaces to directly interact. Krakowiak treats the upper spaces of the classrooms and the lower auditorium as resonating chambers, visually simulating how these two very different sound environments could have affected each other. This mute visualization of sound dispersal was prompted by ikebana itself: its meticulously choreographed set of hand movements, where silence is a method, rather than a mere lack of sound.

Text by Magdalena Moskalewicz. This project was commissioned by Magdalena Moskalewicz and post editorial team as an artist’s response to the Sogetsu Art Center, alongside a number of other contributions to the site on this subject.

The model visualizes the movement of sound through the building and the pace at which the structure is filled by sound.The colors of the balls represent the number of times sound bounces against the walls, as determined by the shape of the building.Thus the changing colors represent the way in which sound is directed through the interior, mapping the acoustics of the space. © 2013 Katarzyna Krakowiak

The animation traces the path of sound reverberating inside the concert hall of the Sogetsu Art Center. It shows how the staircase could have conveyed the sound upstairs, into the classrooms, thus playing the role of the building’s “acoustic soul.” This architectural model, based on archival photographs of the original building, is a simulation of the original space as imagined by the artist. © 2013 Katarzyna Krakowiak

The term “Dusza Schodów”, roughly translatable as “spirit of the staircase”, is an official architectural term existing in the Polish language to describe the empty space created in between consecutive flights of stairs. Krakowiak uses the phrase in a double meaning: as the architectural concept, and also as a metaphor for what in her project becomes the most important part of the building: the vast, vertical sound-carrying passage. © 2013 Katarzyna Krakowiak