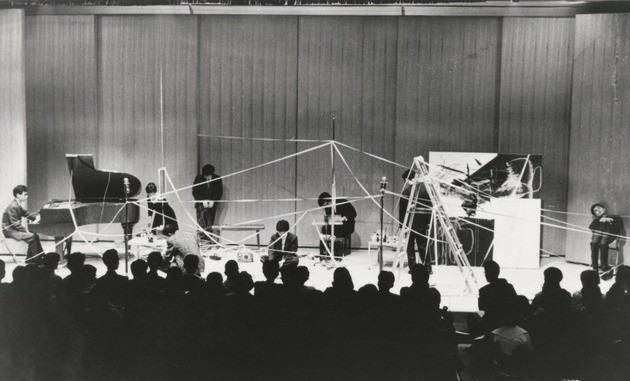

The Sogetsu Art Center (SAC) in Tokyo was a major hub for avant-garde activities between 1958 and 1971, a period of concentrated energy for the experimental arts in Japan. Artists, musicians, designers, critics, writers, and performers gathered at the SAC to test out new experimental practices and to engage in dialogue about new directions in the arts. With a performance hall, regularly scheduled performance and film series, and its own arts journal, the SAC was a space where artists could collaborate and speak across disciplinary boundaries in ways that would have been impossible in traditional museum, concert hall, or academic contexts. Many artists and musicians who were active at the SAC became leading figures in their fields.

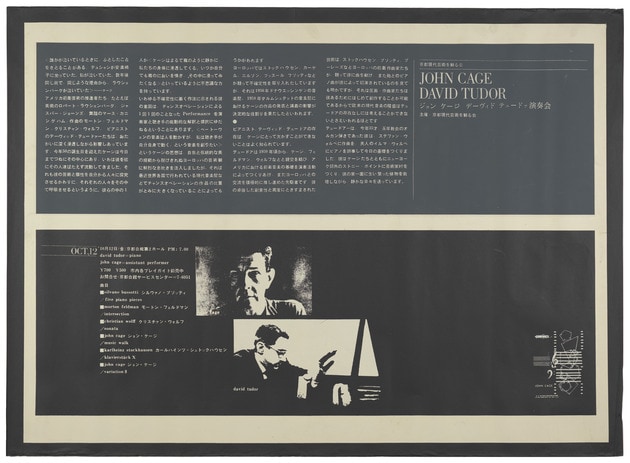

In terms of performance art in Japan, the first documented event in the country that was called a “happening” took place at the Sogetsu Art Center, at Ichiyanagi’s concert in late 1961. Cage, Tudor, and Cunningham all came to Japan for the first time through invitations by the SAC.

Some Historical Background

Preceding the SAC, Sogetsu Ikebana School was founded in 1927 as an ikebana (flower arrangement) school; in 2012, it remains one. Kado (the historical art of flower arrangement) in Japan is said to have originated around the fourteenth century. Rooted in Buddhist practice, it was adopted by the nobility as a leisure activity. Like many traditional Japanese arts—Noh, Kabuki theater, instrumental music and calligraphy—kado spawned many schools, or ryu-ha, each with its own master and distinct style. Sogetsu was one of these.

Teshigahara Sofu (1900–1979), founder of the Sogetsu school, counted among his friends and influences artists such as Dalí, Miró, Gaudí, and Tàpies, and Time magazine described him as the “Picasso of flowers” in a review of his 1955 solo exhibition in Paris.

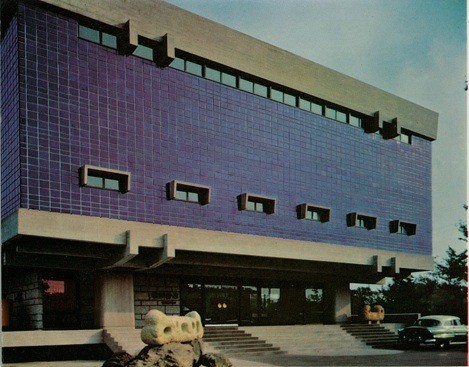

When the Sogetsu Art Center was founded in 1958, Sofu’s son, Teshigahara Hiroshi, who would later be known as an avant-garde filmmaker, became its director. When Sofu opened the new Sogetsu Kaikan, a new building for the Sogetsu school in the Akasaka area (across from the imperial crown prince’s residence), he gave Hiroshi office space for SAC administration and permission to use the concert/lecture hall with moveable seats. Among Tokyo’s young artists, it quickly became known as a center for creative collaborations by the city’s foremost experimenters.

The building, designed by Tange Kenzo, included a concert hall, a recording and electronic music studio, film projectors, and a custom-made vermillion red Bosendorfer piano, which had a distinct aerodynamic shape that was closer to a retro- futuristic spaceship than the classic nineteenth-century grand piano. One of only three pianos of this design, it was custom-ordered especially for the hall. Inside, the design of the concert hall and the lounge spaces was magnificent yet sleek and modern, even by the standards of today, over fifty years later.

As an institution with a concert hall, exhibition space, recording studio, custom-made Boesendorfer piano, administrative staff, and its own journal, the SAC provided small and often loosely structured collectives with favorable conditions for the creation of artistic and social networks. It was especially significant for the history of experimental music in Japan: with a stage and auditorium rather than a gallery as the central space for gatherings at the SAC, music and musicians occupied central places in the programming, particularly during the first half of SAC activity, between 1960 and 1964. Throughout the entire duration of the SAC, film programs were the most consistent and longest-running events.

A Bigger Future? / The End of the SAC

While the SAC as an institution did not close its doors until 1971, many artists and musicians who frequented the Center view the mid-1960s as the end of the SAC as a place of major significance, with interest and energy directed elsewhere, including into more organized, larger-scale projects such as Crosstalk/Intermedia, Orchestral Space, and EXPO ’70.

An uprising by an anti-capitalist group who called themselves the Fesutivaru Funsai Kyoto Kaigi (Joint Struggle for the Annihilation of the Festival) forced the termination of the 1969 Film Art Festival. It is ironic that these critics viewed the SAC as an institution for legitimating avant-garde art, when in fact, it originally set out to provide a place for artists outside the world of commercial art (Yamaguchi 2002, 120). It seems a bit extreme and unfortunate that an experimental film festival would become the target of anti-capitalist violence—how lucrative, really, has experimental film ever been? But the SAC itself had already changed, too. As artist Yamaguchi Katsuhiro puts it, by the late 1960s, “Sogetsu itself began to change, but that means the connections between people also changed”. In 1970, a scandal involving a tax evasion charge against Sofu dealt a final blow to the SAC.