What does it take to perform an object? Curator Fujii Aki, who performs in the 2011 video version of Endless Box presented in this essay, describes the process from a curatorial and creative perspective. Scroll down to see the resulting video, directed by Yamashiro Daisuke.

Shiomi Mieko’s works do not consist of single objects that present a closed, self-sufficient world, but always hold the intrinsic potential for progress and transfiguration. Her work goes beyond intermedia, in the sense of work that spans multiple media. It extends to a realm where sounds, words, moving images, and objects are interchangeable according to certain rules and form an integrated whole. Indeed, it embodies Shiomi’s concept of “transmedia,” in which a work in one particular medium serves as the catalyst for a work in another medium based on the same concept. Shiomi’s work explores time, place, balance, direction, shadow, gravity, and related concepts, and is grounded in everyday experiences, inviting a wide range of interpretations by different viewers and generating an open field of meaning that expands like ripples in water. When we featured her work as part of the exhibition MOT Collection Chronicle 1964-: Off Museum at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (Feb. 4–May 6, 2012), exhibiting the work presented a dilemma, as a museum is restricted to the existing vocabulary of display models even when showing work such as this, which possesses a dynamism that transcends the rigid confines of glass cases and the static relationship between artwork and viewer. In an attempt to communicate even a bit of this inherent dynamism, I organized a talk by the artist (see the edited transcript here) and a performance based on the exhibited work, and I planned the production of a video documenting Endless Box shot by the artist Yamashiro Daisuke.

Endless Box

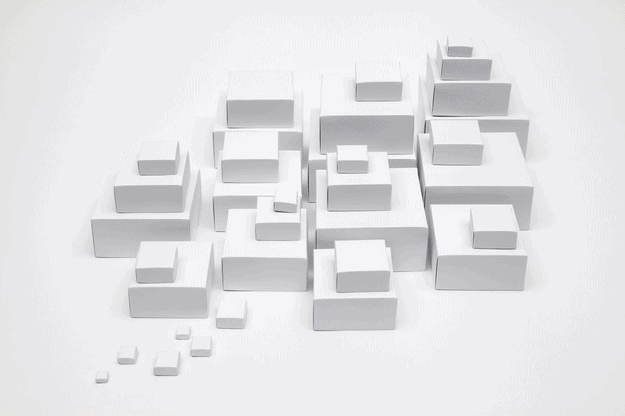

Endless Box consists of thirty-four interlocking paper boxes of diminishing size (Fig. 1). Each box nests inside a larger one so that they all fit inside the largest box. The entire assemblage is wrapped in a light violet-colored cloth and housed in a wooden box. Two large sheets of Japanese paper (approximately 31 x 43 in. [78.8 x 109.1cm]) are used to make the entire thirty-four-box ensemble, and each sheet is folded in the same manner. Perhaps because the paper contains a fluorescent brightening agent, it has a clear white luster tinged with blue (although this will likely fade with age), which harmonizes with the violet of the cloth. Since 1963 Shiomi has created approximately twenty-five sets of these boxes entirely by hand.

She has written of this work: “I was thinking about transparent music, music in which nothing could be heard but the ceaseless passage of time. And I thought, perhaps this could be presented to the senses not necessarily through sound, but by some other method. . . . I emptied my mind, and what came into it was an image of the origami boxes I used to make as a child. No matter how many boxes you opened, there would always be a slightly smaller one inside, and each time you opened a box, it was as if you were entering yet another, deeper layer of time. A white object that acts as a kind of visual diminuendo, focusing a person’s awareness and conveying the endless passage of time with a sort of sensuousness, beckoning the person onward. . . . I decided to try to re-create these boxes. I calculated the sizes so that one set could be made with two sheets of 78.8 x 109.1cm sheets of paper and selected paper with the pliability, tension, and strength required for folding, in a white that sometimes appeared tinged with violet, depending on how the light struck it.”1Shiomi Mieko, Fluxus to wa nanika? Nichijo to art o musubitsuketa hitobito (What is Fluxus? Connecting art and the everyday; Tokyo: Film Art, November 2005), p. 74. The artist goes on to say that the rural environment in which she spent her youth was a major inspiration for the work: a soft lavender mist settling slowly over the pastoral landscape as she made her way home at dusk; lingering evening sunlight illuminating the trembling white petals of a flowering calabash plant pushing its way up blithely from a haystack; imagining the music she wanted to play, because the only piano she could use was at school.2Shiomi, in an interview at her home, November 16, 2011. In this environment, Shiomi experienced day-to-day life with heightened acuity, through multiple senses and perhaps indeed her entire body. We can easily imagine that this eventually led to her creation of “intermedia” pieces such as Endless Box.

Production of the Video

As described above, Endless Box is a piece that gives tangible expression to the ceaseless passage of time, but when it is exhibited in a museum, the static “object” status of the progression of nesting boxes tends to be amplified. The beauty of the white boxes of extremely simple construction comes across, but the visual diminuendo ringing out amid the silence of time’s relentless passage is frozen in the imagination, as if we are seeing the fossilized imprint left behind after an action (music) has ended.

Under these circumstances, in order to emphasize the temporal element, and to allow viewers to experience the imaginary music vicariously, a decision was made to videotape a performance by the artist and to present this video alongside the boxes. This decision sprang partly from an archival interest in documenting the artist’s actions and partly from a desire to highlight the artist’s uniqueness.3Precedents for this kind of video documentation produced by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo include works showing Kikuhata Mokuma giving precise instructions for the display of his Slave Genealogy (By Coins) and Nakanishi Natsuyuki preparing his Clothes Pins Assert Churning Action for display.

However, while Shiomi agreed to the idea of making a video, she suggested that the performer be anonymous. She felt that Endless Box ought to stand on its own, independent of its creator, and that anonymity was in keeping with the ideals of Fluxus. In contrast to a curator’s concept of documenting the work’s creation and showing a performance by the artist to emphasize her uniqueness, Shiomi’s idea was to make the video a vehicle for exploring hitherto unseen aspects of the work. This reflects the fact that Shiomi’s work, like the performance work of other Fluxus members, is intended to be interpreted and performed by a wide range of people and to remain an ongoing event, eternally in the present tense. The museum agreed to her proposal, and it was decided that I would be the performer in the video.

I was thinking about transparent music, music in which nothing could be heard but the ceaseless passage of time.

Shiomi formulated several ideas for the production of the video. (1) In a dark space, nothing would be visible in the frame except hands and a table, and the hands would reach out and lift the “lid” of the outer box to reveal a smaller box inside it. Once removed, the “lid” would disappear from the frame, and the hands would repeat the process, opening the next box, with the performer using left and right hands alternately. The final, smallest box would be held in the palm of the hand and then placed on the table, concluding the performance. (2) Opened boxes would be laid out and piled up one by one in an array resembling the large and small islands of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea. (3) If performing tasks such as these repeatedly on video seemed too difficult, the entire process could be shot as a series of still photographs (resembling animation), or with time-lapse photography, and edited afterward. In any case, the artist felt that a creative approach ought to be taken to the performance and its filming and editing, so as to make a the new video work based on Endless Box an exercise in “transmedia.”

The video was shot by the artist Yamashiro Daisuke.4Yamashiro Daisuke is a member of the artists’ group Nadegata Instant Party and has a strong interest in Fluxus. Work by Nadegata Instant Party was featured in the MOT Annual 2012: Making Situations, Editing Landscapes (curated by Nishikawa Mihoko, October 27, 2012–February 3, 2013). It was based on Shimio’s idea (1), with some elaborations: for example, an acrylic panel was placed beneath the hands to lend depth to the image. To emphasize the passage of time, the video was shot in one continuous six-and-a-half-minute take. I attempted to move my hands smoothly and efficiently so as not to distract from the boxes. In the course of repeatedly opening box after box, a rhythm arose naturally, and I underwent a magical experience in which the progression of fleeting moments gave rise to a transparent, soaring sense of endlessness. The resulting video was displayed alongside the boxes.

To the people of the 30th century

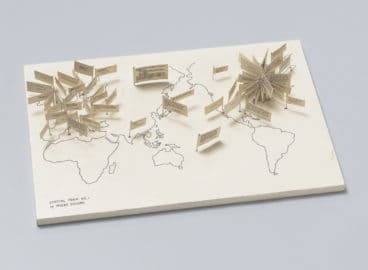

The legend “dedicated to the people of 30th century” [sic] appears at the end of Shiomi’s self-published booklet Spatial Poem documenting a series of nine international mail events that the artist carried out over a ten-year period starting in 1965. The dedication is a paean to the human race and human endeavor and indicates that the work is an invitation for future generations to participate in the project.

Shiomi gave participants in each event instructions to perform and document specific actions, such as writing a word on a card and placing the card somewhere, dropping an object, opening something that had been closed, or listening to the sounds around them. No special knowledge or skills were required and all of the actions involved natural phenomena or small, mundane gestures blending sound, word, and nature—actions that anyone could understand, perform, and enjoy equally.

While growing out of the artist’s personal history—she was a poetry-loving child raised by musically inclined parents in picturesque natural surroundings—Shiomi’s work is also the product of a concerted intellectual endeavor to create something that is neither art nor music alone but transcends and underlies both. This endeavor was shaped by her encounter with Fluxus, which came after a lengthy trial-and-error exploration of the genesis of what we call music. In the realm of primordial and undifferentiated actions, Shiomi identified those with poetic resonance and presented them as works of art, sharing the results through a wide range of communicative media and opening up new channels of “intermedia” and “transmedia” expression. To the receiver, works such as these brim with the potential for perception of the unknown, perception that bridges the abyss of time and space. The receiver in turn becomes a creator, and the artist becomes an interpreter of the work, engendering a sustained dialogue in varying media. Even when taking small trivialities as a starting point, Shiomi’s creations remain open systems that progress, accompanied by a stream of image associations—coexisting, persisting, endless.

As museums amass and exhibit collections of works that have passed through many hands, bringing them together to document the past and usher in the future, I believe they must give close regard to the temporal dimensions inherent in each work, and to the history to which it bears witness.

Note: This essay was translated by Colin Smith and edited for publication on post. The original Japanese text was published in the 2012 Annual Report for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (MOT). The Japanese version is available here on the MOT website. Fujii Aki’s text starts on page 105 of the linked PDF.

- 1Shiomi Mieko, Fluxus to wa nanika? Nichijo to art o musubitsuketa hitobito (What is Fluxus? Connecting art and the everyday; Tokyo: Film Art, November 2005), p. 74.

- 2Shiomi, in an interview at her home, November 16, 2011.

- 3Precedents for this kind of video documentation produced by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo include works showing Kikuhata Mokuma giving precise instructions for the display of his Slave Genealogy (By Coins) and Nakanishi Natsuyuki preparing his Clothes Pins Assert Churning Action for display.

- 4Yamashiro Daisuke is a member of the artists’ group Nadegata Instant Party and has a strong interest in Fluxus. Work by Nadegata Instant Party was featured in the MOT Annual 2012: Making Situations, Editing Landscapes (curated by Nishikawa Mihoko, October 27, 2012–February 3, 2013).