In this text, Cape Town-based writer Nkgopoleng Moloi muses on the hauntings prompted by Sue Williamson’s For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990). On view in the David Geffen Wing until October 25, 2021, Nkgopoleng considers the passbook, recorded and framed by Williamson, as an object that has survived to bear testimony to the presentness of the past, evoking this intimate relic’s ability to prompt a secondary witnessing.

South Africa’s history is abundantly captured as institutional memory in the form of museums, state archives, and historical sites. Because of this ubiquity, it is easy to reach a point of “apartheid fatigue,”1Izelde van Jaarsveld, “Affirmative Action: A Comparison between South Africa and the United States,” Managerial Law 48, no. 6 (December 2000): 1–48.a disturbing mental state in which one feels as though they have reached their capacity for considering apartheid and its effects. Sometimes driven by apathy, this condition is characterized by a belief that history is either irrelevant and of no practical value or otherwise resolved. But, of course, as South Africa is one of the most unequal and unjust societies in the world, its history of institutionalized racism and oppression is nowhere near resolved. It is very much alive, continually unfolding and opening itself up to the horrifying potential of repeating itself.

What remain absent within this context of profuse institutionalized recollection and remembrance are objects and sites that accurately and sufficiently hold the collective memory of the majority. A large number of South Africans do not see themselves or their narratives presented in their country’s institutions. This reality is largely reflected through movements organized by a younger generation of South Africans, such as #rhodesmustfall and #feesmustfall, in which students took to the streets in protest, calling for free, quality, and decolonized education; an end to outsourcing practices within universities; and the removal of colonial monuments and artifacts, among other demands.

Often, institutionalized sites of memory embody a singular and easily digestible narrative, one of forgiveness and reconciliation within a “rainbow nation” based on the ideal of an equal, multiracial, and reconciled South Africa. This is the legacy Nelson Mandela wished to leave behind. As he declared in 1994, “We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.”2Kim De Raedt, “Building the Rainbow Nation: A Critical Analysis of the Role of Architecture in Materializing a Post-Apartheid South African Identity,” Afrika Focus 25, no. 1 (June 2012):7–27, https://doi.org/10.21825/af.v25i1.4960.The promise of a “rainbow nation” has remained largely unfulfilled as the narrative of a “nation at peace with itself” systematically overlooks economic and social injustices, and moreover, further incites violence through exclusion and alienation.

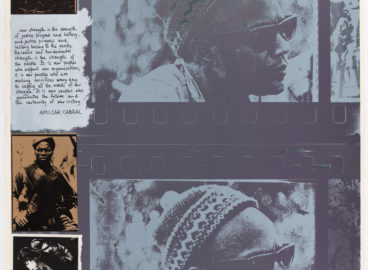

Through a participatory approach to documenting and accounting for the past, Sue Williamson works against the limits of this narrative, creating a potential for bridging the gap between historicized memory and embodied memory. Her practice recalls the past through the act of remembrance and recollects it through the work of archiving.

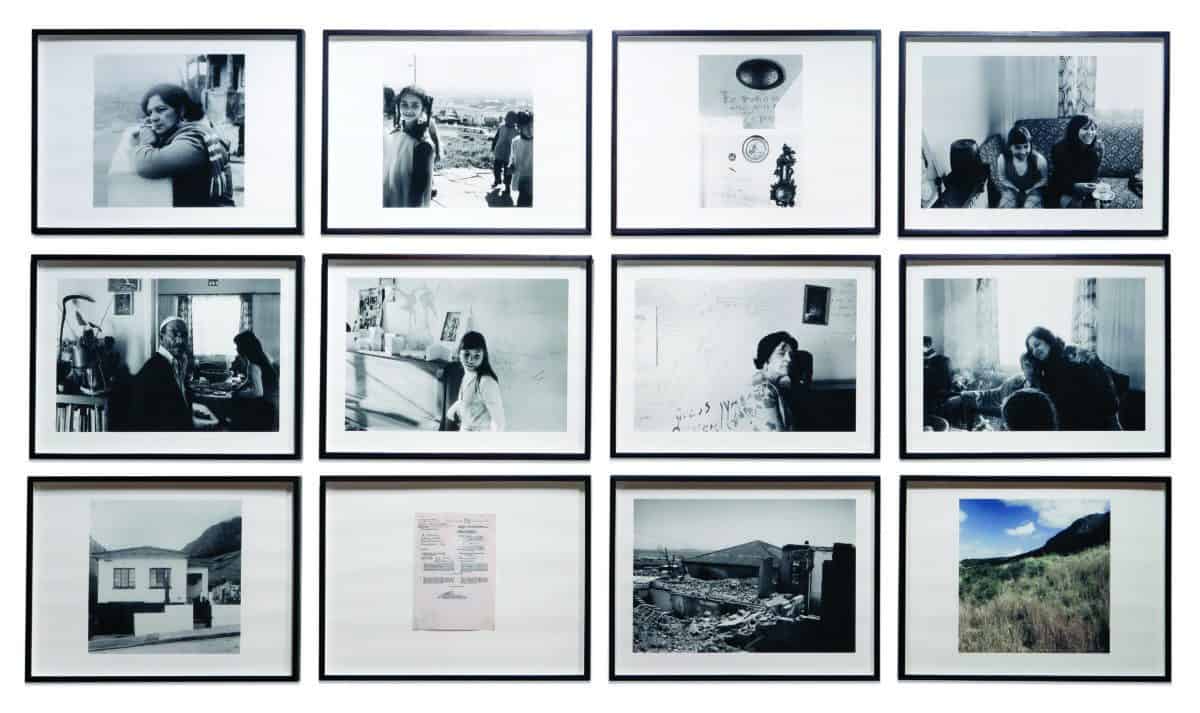

Having trained as both a journalist and a printmaker, Williamson coalesces installation, video, and photography within her practice. She works closely with and intimately engages her subjects as collaborators, as is demonstrated in projects such as There’s something I must tell you (2013), in which she recorded conversations between veteran women activists and their granddaughters, and Last Supper at Manley Villa (1981), in which she documented the District Six forced removals through the story of the Ebrahim family on the eve of their removal. The forced removals were a result of the Group Areas Act of 1950, which declared District Six a “whites-only” area. People not classified as “white” or European under the apartheid regime were relocated to places such as Langa township (designated for Africans) and the Cape Flats (designated for “coloured” people). The process of forced removals by the apartheid nationalist government spanned sixteen years, beginning in 1966, and saw more than sixty thousand residents removed from District Six alone. Williamson notes: “On August 2, 1981, Naz and Harry Ebrahim had celebrated Eid with their family and friends at Manley Villa for the last time. The first ten photographs in this portfolio were taken on and around that day. A few months after that, the comfortable family home was demolished. The last photograph in the portfolio was taken in 2008 and records the empty spot where Manley Villa once stood.”

Williamson often speaks of her practice as not merely documenting but also bearing witness. As a witness, she’s not offering up moral lessons or sketching out an ethical position, she is simply telling the story as it is. Speaking in relation to Williamson’s practice, Professor Ciraj Rassool posits that “the position of the artist who works with historical experience is necessarily a difficult one.”3Ciraj Rassool, “District Six,” in Sue Williamson: Life and Work, ed. Mark Gevisser (Milan: Skira, 2015), 53.For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990) emerges from this difficult position. It is not an easy work to engage.

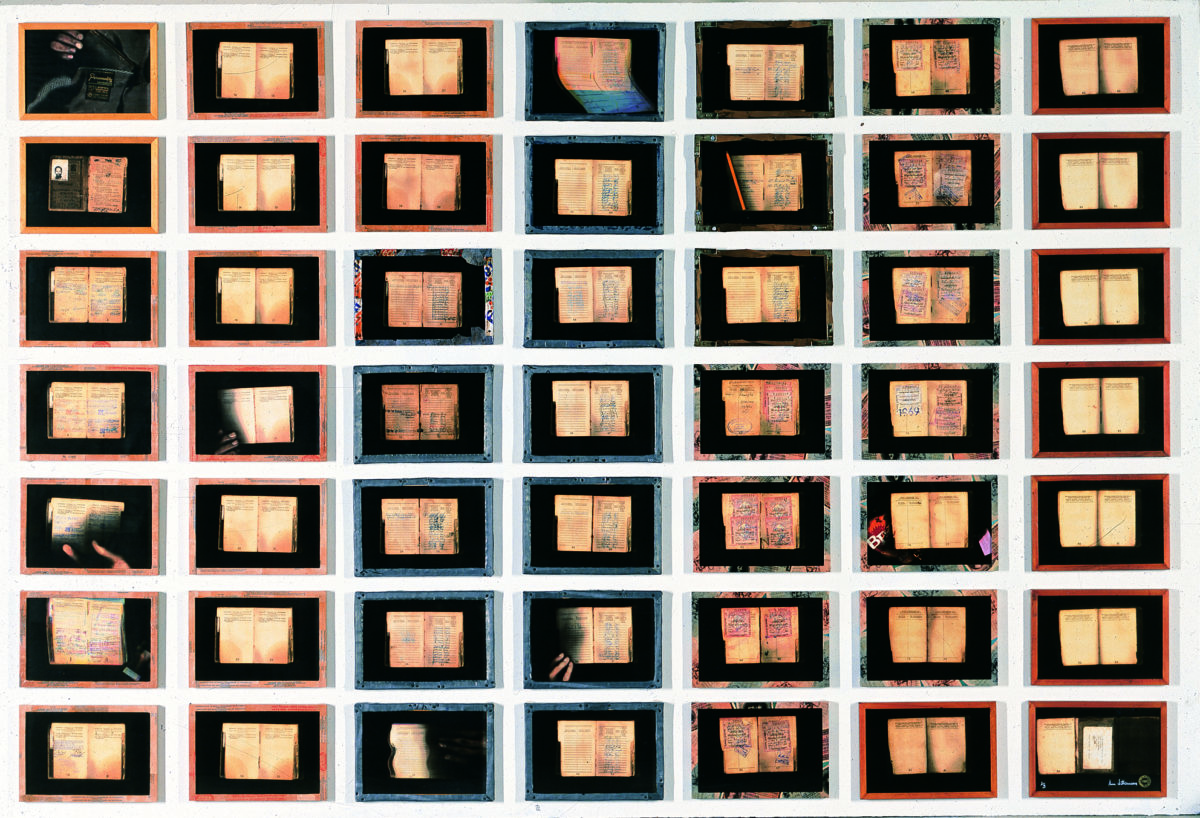

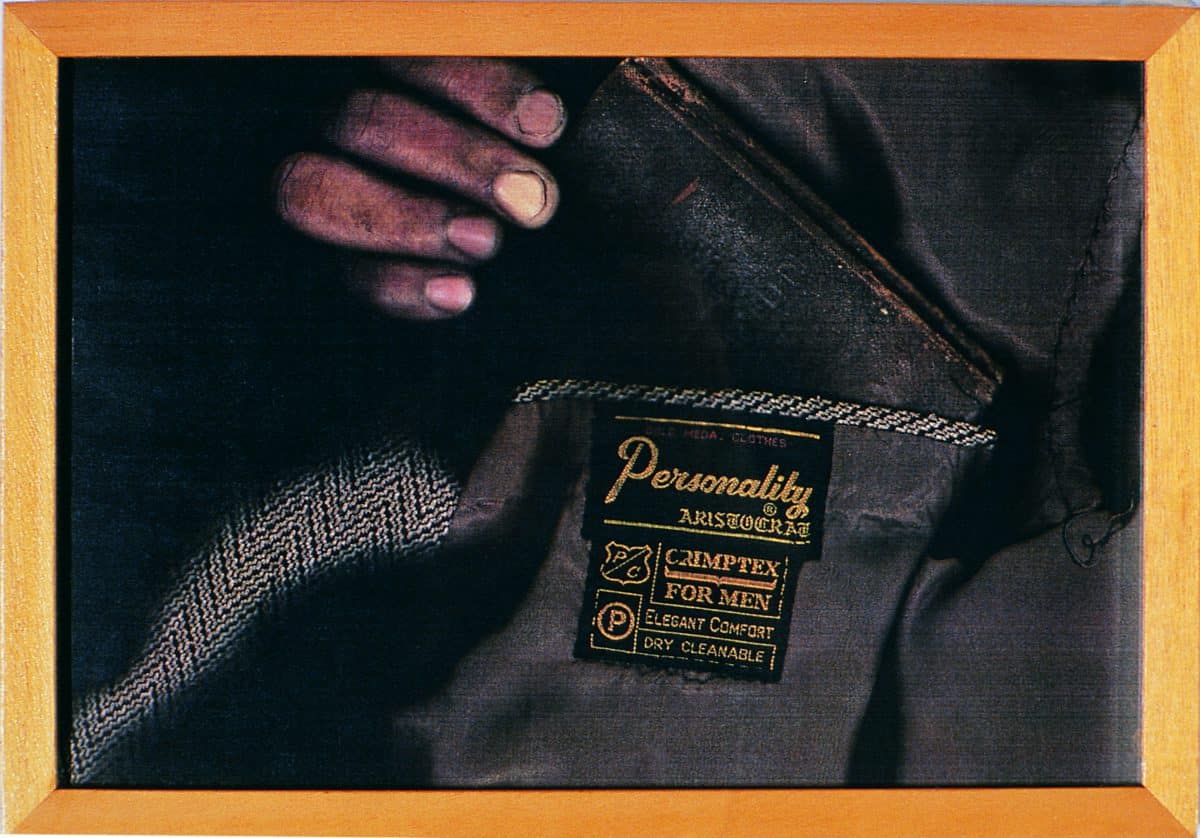

In For Thirty Years Next to His Heart, Williamson turns her attention to an emblem of white supremacy and oppression: the passbook. The work documents forty-nine pages from the passbook of a Black man named John Ngesi. Produced from a Canon color laser printer (a new and rare technology at the time) arranged in a seven-by-seven grid (a narrative sequence of forty-nine images read left to right and top to bottom), the photocopies are enclosed in artist-made frames. The choice of framing materials—copies of old currency and images of soft drink cans—is significant. This decision takes its inspiration from the common local practice in South African township homes of using colored paper and packaging from ordinary consumer goods to make frames for photographs as well as, in some cases, wallpaper. For Thirty Years Next to His Heart is the artist’s most well-traveled piece, and editions are currently held in the collection of the Museum Africa in Johannesburg and The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

A document required by law, the passbook embodies the complexities of (im)mobility for Black people in South Africa, who under apartheid, could not work or move freely between different parts of the country without proper documentation. The history of so-called pass laws can be traced to the practice of slavery in the Cape colony, from as early as the 1700s. The Khoikhoi people, who had lost their land to colonial landowners, were forced into labor and required to carry “permission documents,” which regulated their movement to and from the farms on which they worked.“4Pass laws in South Africa 1800–1994,” South African History Online.The evolution of passes and laws culminated in the Native (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 and later the Native Laws Amendment Act, 1952, which relegated Black people (particularly Black men) to the status of “temporary sojourners” within urban areas, a condition that persists to this day. The passbook underpinned a system of cheap migrant labor rendered under very difficult and unfair conditions. Based on figures supplied in the Annual Report of the Commissioner of South African Police (1917–20, 1925–33, 1935–39, 1941–79/80), University of Cape Town professor Michael Savage estimates that more than seventeen million Africans were arrested and prosecuted under various pass laws and influx control regulations in South Africa between 1916 and 1984.5Michael Savage, “The Imposition of Pass Laws on the African Population in South Africa 1916–1984,” African Affairs 85, no. 339 (April 1986): 181–205.

When I visited her studio, Williamson showed me Ngesi’s passbook. Secured between the hard flesh of the cover, pages detailing his life are yellowed and aged —Signature. Date. “Report to the local labour bureau at Langa.” Signature. Date. Permitted to remain in the prescribed area. Signature. Date. Influx control registration. Signature. Date. Kensington Inn Hotel. Signature. Date. Rural reserve. Signature. Date. Discharged. Commenting on why Ngesi had still carried this document years after the law had been repealed, the artist explained, “I realized that although it was a hated instrument of control, it was also his security and habit of years.” When, after completing her artwork, she attempted to return it to the old man, he refused to accept it. It was as if a huge burden had been lifted from his shoulders.

As its title suggests, For Thirty Years Next to His Heart is personal. There’s a kind of paradox suggested, the intimacy of having this abhorred document stored next to its owner’s heart, in the pocket of his suit jacket, against its function as a register of gross violations of human rights. The everydayness contained in the gesture of repeatedly removing the passbook from his pocket reveals the weird intimacy of violence and the banality of evil. Reflecting on these past injustices, Williamson notes, “I also had to sign a pass for a man who worked as a gardener for me, Lennox Cengani. I had to pretend that he worked for me full time and pretend that I was paying him a very low salary. I didn’t want to be complicit but if I hadn’t signed, Lennox would not have been able to work.”

If For Thirty Years Next to His Heart is meaningful, it is because it offers the opportunity to deeply interrogate the effects of how memory is recorded. The work presents us with the agonizing problem of what to do with the pages of history. As members of a society that is still plagued by injustice and deep inequality, we are all affected by this problem. The question of which memory is being memorialized is raised. Is it Ngesi we are remembering? Is it the brutality of the system? If we consider historical amnesia as repression of not only the past but also an imaginable future, what do we do with this remembering in a society that is anxious to forget?6Fredric Jameson, Leonard Green, Jonathan Culler, and Richard Klein, “Interview: Fredric Jameson,” Diacritics 12, no. 1 (Autumn 1982): 72–91, https://doi.org/10.2307/464945. If the future is where healing and reconciliation lie, how do we fashion a smooth passage between the past and the future when the past lingers while the future remains unreachable, and thus more and more elusive?

- 1Izelde van Jaarsveld, “Affirmative Action: A Comparison between South Africa and the United States,” Managerial Law 48, no. 6 (December 2000): 1–48.

- 2Kim De Raedt, “Building the Rainbow Nation: A Critical Analysis of the Role of Architecture in Materializing a Post-Apartheid South African Identity,” Afrika Focus 25, no. 1 (June 2012):7–27, https://doi.org/10.21825/af.v25i1.4960.

- 3Ciraj Rassool, “District Six,” in Sue Williamson: Life and Work, ed. Mark Gevisser (Milan: Skira, 2015), 53.

- 4Pass laws in South Africa 1800–1994,” South African History Online.

- 5Michael Savage, “The Imposition of Pass Laws on the African Population in South Africa 1916–1984,” African Affairs 85, no. 339 (April 1986): 181–205.

- 6Fredric Jameson, Leonard Green, Jonathan Culler, and Richard Klein, “Interview: Fredric Jameson,” Diacritics 12, no. 1 (Autumn 1982): 72–91, https://doi.org/10.2307/464945.