In this text, Delia Solomons brings together Marisol’s sculpture Love and Frank O’Hara’s poem “Having a Coke with You” to explore their shared investigations of the personal in a capitalistic landscape, queer eroticism, global Cold War politics, and stoppered versus flowing communication.

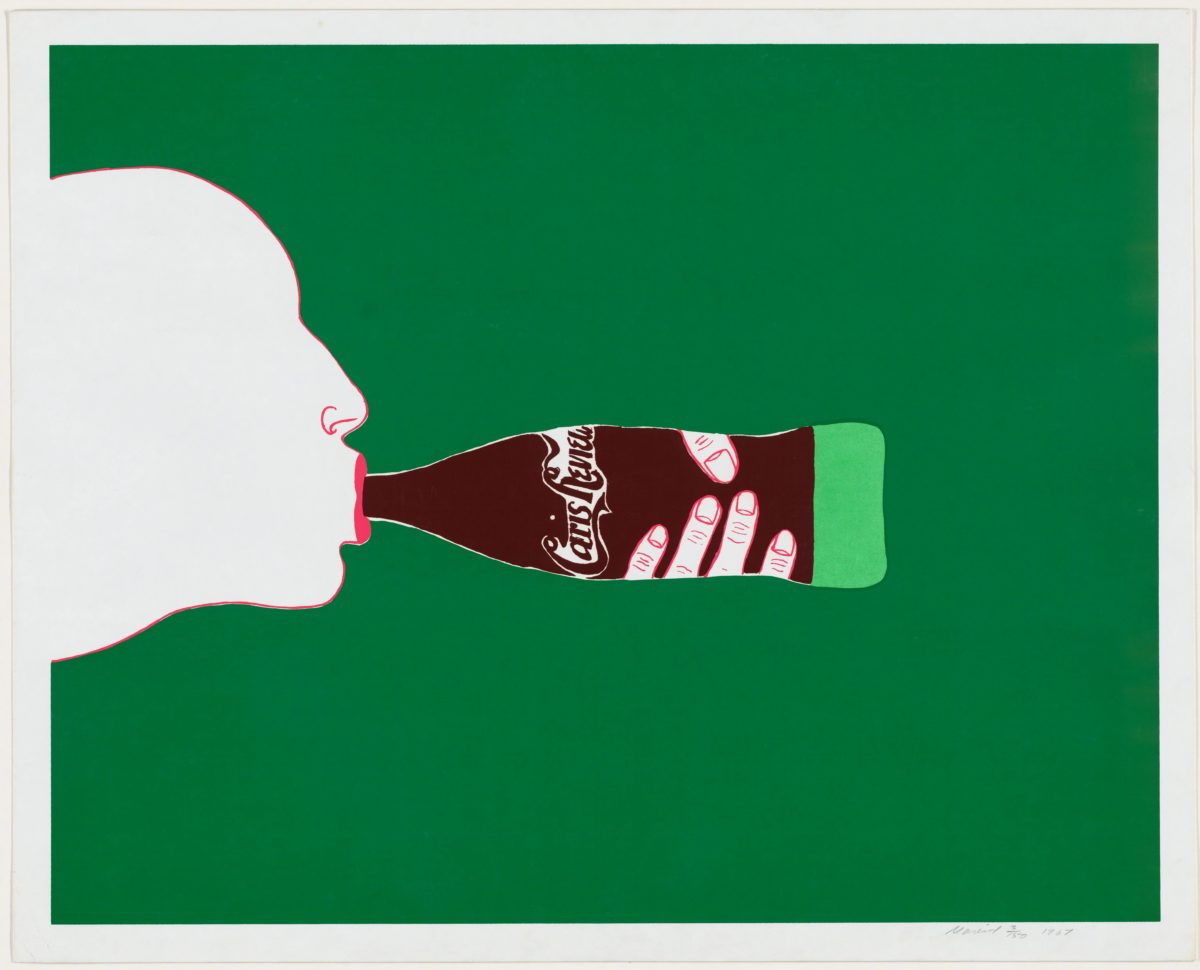

In Marisol’s Love (1962), the cast mouth fellating a Coca-Cola bottle establishes a potent conflation of sexual and consumerist desire. Love, generally considered the artist’s most Pop artwork, is often showcased alongside other Coke-referencing works by artists like Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselmann (the latter purchased Love in 1962).1Tom Wesselmann purchased Love from the last Tanager Gallery group show in January 1962. See Irving Sandler, “Oral History Interview with Tom Wesselmann, 1984 January 3–February 8,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-tom-wesselmann-12439#transcript. However, Love’s closest connection may lie not among fellow visual artworks at all, but rather with a literary contemporary. The sculpture bears an uncanny relationship to the tender love poem “Having a Coke with You” (1960)2Read full poem here or click here to view O’Hara reading “Having a Coke with You” in 1966, recorded for Richard Moore’s documentary series USA: Poetry. written by Marisol’s friend: the poet and MoMA curator Frank O’Hara.3Marisol and O’Hara became friends in the 1950s, circulating in the same New York social/cultural scenes and vacationing with an intimate cohort on Long Island during the summers. O’Hara mentions Marisol in his poem “Macaroni” (1961). Both works have garnered much attention and each is considered a centerpiece of its creator’s oeuvre, yet scholars have never linked them. This short essay draws together sculpture and poem to explore their shared investigations of the personal in a capitalistic landscape, queer eroticism, global Cold War politics, and stoppered versus flowing communication.

Love and “Having a Coke with You” both center Coca-Cola within a sexual or romantic encounter. In the sculpture, the bottle itself manifests as sexual partner. In the poem, O’Hara enjoys a Coke with the true subject of his admiration: an unnamed companion (ballet dancer Vincent Warren) who is comically, dotingly compared to and found more wonderful than a host of other delights like viewing art and traveling through Spain. Marisol and O’Hara appropriate the language of advertisements when they engage the soda. The sculpture showcases the product so prominently that the human is demoted to pedestal, and the poem opens with language befitting an ad slogan: “Having a Coke with you is even more fun than . . .” However, both of them pivot swiftly from the alienating, dehumanizing commodity to the deeply personal through not only the scenes depicted (the sculpture’s exposed act and the poem’s romantic romp through New York), but also the mode of address. Just as Marisol employs a cast of her own mouth, O’Hara mobilizes conversational first-person narration. Yet, while artist and poet seem to offer themselves rather intimately through these confessional devices, they employ distancing measures to avoid self-exposure—Marisol via her deadpan tone and exclusion of identifying features like eyes, and O’Hara via his carefully cultivated Personism.4In his non-manifesto “Personism” (1959), O’Hara proposes a mode of writing that generates “the illusion of intimate talk between I and you,” yet is at once “transparent and opaque . . . showing all but disclosing nothing . . . [T]he anticonfessional poet reveals all, only to reveal nothing about himself.” See Marjorie Perloff, Frank O’Hara: Poet Among Painters (New York: George Braziller, 1977), 26; and Terrell Scott Herring, “Frank O’Hara’s Open Closet,” PMLA 117, no. 3 (May 2002): 418.

In the early 1960s, a time of state-sanctioned homophobic repression and tremendous social pressures surrounding heteronormativity, Marisol and O’Hara created works that visualize queer and nonbinary eroticism or companionship. In Love, the cast mouth may be Marisol’s but it registers as ambiguously sexed. The bottle-companion simultaneously assumes phallic identification and retains its famously “womanly” hourglass form.5Sid Sachs, “Beyond the Surface: Women and Pop Art 1958–1968,” in Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958–1968, eds. Sid Sachs and Kalliopi Minioudaki (Philadelphia: University of the Arts, 2010), 34. Thus, within this startlingly direct, pared-down iconography, possible couplings emerge, remix, and multiply.6For a brief discussion of other works by Marisol that “defy a normative heterosexual reading,” see Rachel Middleman, Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 2. In a related though hardly identical fashion, O’Hara’s lyric poem offers at once a specifically homoerotic anthem and an open expression of devotion adaptable to any two people no matter how they identify. On one level, “Having a Coke with You” celebrates romance particularly between two men, generating, in José Esteban Muñoz’s words, “a vast lifeworld of queer relationality, . . . [and] a relational field where men could love each other outside the institutions of heterosexuality.”7José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 6, 9. In the introduction to this pivotal book, Muñoz articulates the potential for queer futurity through his discussion directly relating O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You” to a 1950s drawing by Warhol that depicts a Coke bottle with a single rose, an image that remarkably links the three works by Marisol examined in this essay. At the same time, any person can inhabit the speaker’s role to profess these words to their own beloved. The poem’s “you” resists gendered prescription in every line except one, which declares the addressee “look[s] like a better, happier St. Sebastian.” O’Hara devotes lovingly specific language not to gendered or sexed markers, but rather to time spent together: “in the warm New York 4 o’clock light we are drifting back and forth / between each other like a tree breathing through its spectacles . . .”

Vibrant, fun affection wins the day in O’Hara’s poem: his lover’s movement is more beautiful than Futurism, his companionship bests a “drawing of Leonardo or Michelangelo that used to wow me,” and his vivacity renders all statuary comparatively “still . . . solemn . . . [and] unpleasantly definitive.” The poet pities inert subjects in art because “it seems they were all cheated of some marvelous experience / which is not going to go wasted on me which is why I’m telling you about it . . .” In contrast, Marisol ossifies a human encounter into sculpture/commodity. Mouths may be central to both poem and sculpture, but where O’Hara references “breathing,” “smiles,” and “telling,” Marisol puts forth a stoppered, frozen mouth. Marisol is indeed less optimistic. For O’Hara, the commodity “could be emptied of its content and made into a vessel for human interconnection.”8Jasper Bernes, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017), 43. Marisol couldn’t so readily set aside the repressive commodification of life. She establishes an obdurate metaphor between consumerism and sex, communicated through an imaged encounter that toggles with deeply troubling ambiguity between consensual and forced. One moment, Love expresses genuine craving for sweet sodas and intimate sex-positive connection, supported by the sculpture’s title and sensual zooming in on the point of contact. The next instant, viewers confront a blinded, fragmented, disempowered figure with a bottle aggressively shoved in their mouth. Seen in this light, the sculpture invokes sexual violence (“brutal fellated rape”)9Sachs, “Beyond the Surface,” 34. and the sinister corporatization that force-feeds people products and envisions individuals as mindless, indistinguishable consumers whose value lies only in their roles as drinkers or potential drinkers of Coke.

By midcentury, Coca-Cola had already become an arch emblem of US consumer society and its economic and cultural imperialism abroad. In 1950, a Time magazine cover depicted the company feeding its product to a happily hypnotized, infantilized world. By 1962, the soda’s global consumption reached 70 million in 115 countries, having doubled its overseas sales in only five years.10“70 Million Cokes a Day,” New York Times, October 23, 1962, 70. As a Paris-born, Venezuelan-American artist scrutinizing US consensus culture and US–Latin American relations, Marisol was certainly aware of the reputations of the Coca-Cola Company and the United States abroad as interventionist superpowers seeking to gain corporate and political advantage in the Cold War.11I discuss Marisol’s engagement with US–Latin American Cold War frictions in “Marisol’s Antimonument: Masculinity, Panamericanism, and Other Imaginaries,” Art Bulletin 102, no. 3 (Fall 2020): 104–29. Love, which depicts Coke flowing southward as it’s consumed by an ambiguously universal or specifically Venezuelan person, perhaps prefigures other artworks that use Coca-Cola to address US presence in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s. For example, Brazilian conceptual artist Cildo Meireles demanded that “Yankees Go Home!” in Insertions into International Circuits: Coca-Cola Project (1970) and Antonio Caro invoked the Coca-colonization of his country in Colombia Coca-Cola (1976). Love stops short of protest due to the unsettling fact that its drinker can be read as either eager participant or wronged victim. This very ambiguity establishes an apt metaphor for the gamut of dynamics comprising US–Latin American relations during the Cold War. US actions ranged from economic aid to the disastrous Bay of Pigs and the installation of violent dictatorships, which garnered Latin American reactions ranging from ready alliance to enraged dissent.

“Having a Coke with You” also brushes against the context of the global Cold War. O’Hara wrote the poem four days after his return from Spain, where he had been installing MoMA’s exhibition New Spanish Painting and Sculpture (1960), and the first two lines even chart his itinerary.12Brad Gooch, City Poet:The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara (New York: Knopf, 1993), 346. Brian Glavey, “Having a Coke with You Is Even More Fun Than Ideology Critique,” PMLA 134, no. 5 (October 2019): 999. The poem goes on to reference Futurism and sculptures by Marino Marini, which O’Hara would send to Milan a week later for the show Twentieth Century Italian Art from American Collections (MoMA, 1960). Through his curatorial work, O’Hara contributed to MoMA’s midcentury International Program, which famously circulated exhibitions abroad, in part to curry favor for the Western Bloc and extol US cultural power as a producer and collector of art. “Having a Coke with You” can be interpreted as imparting a related nationalistic message: the speaker’s experience drinking a quintessentially US product with his US lover outshines hallmarks of the European artistic canon from the Renaissance to modernism.

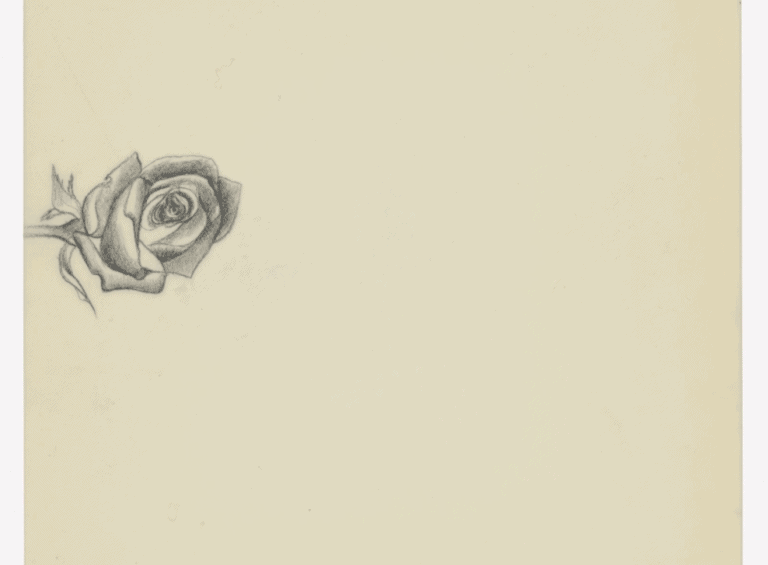

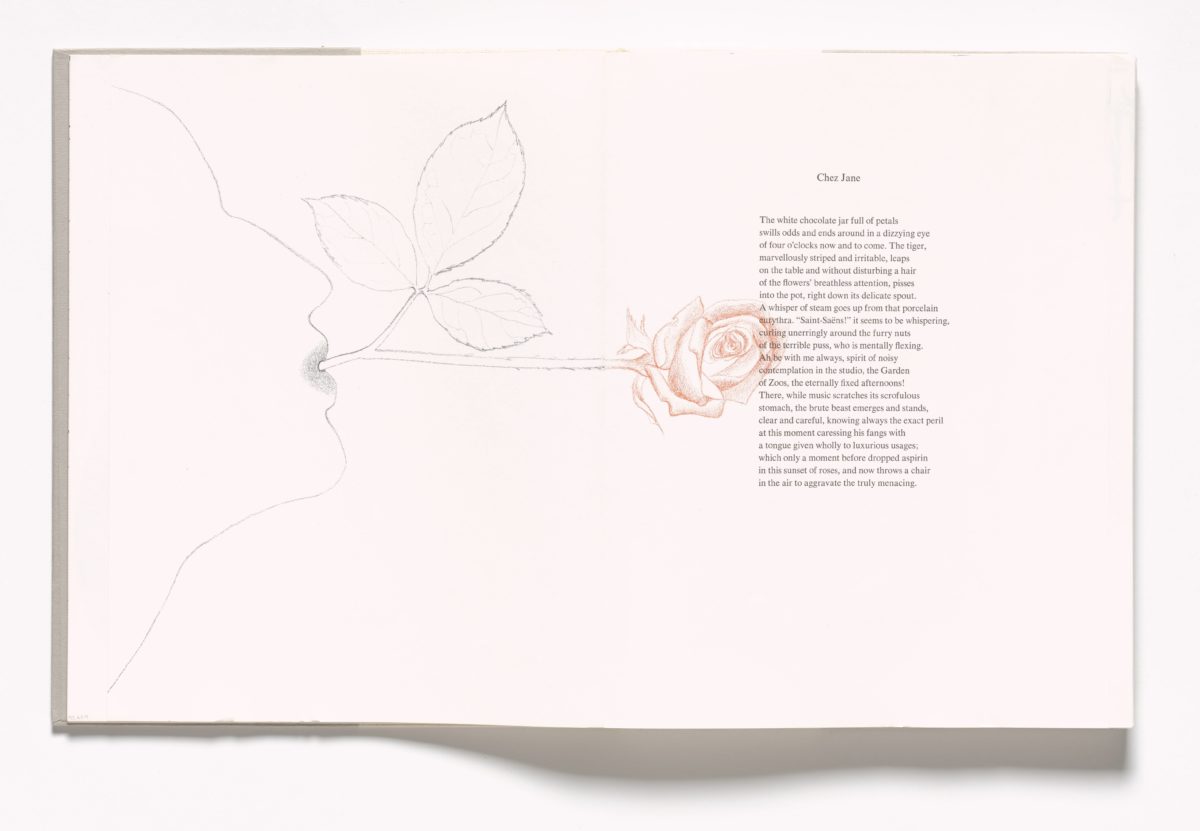

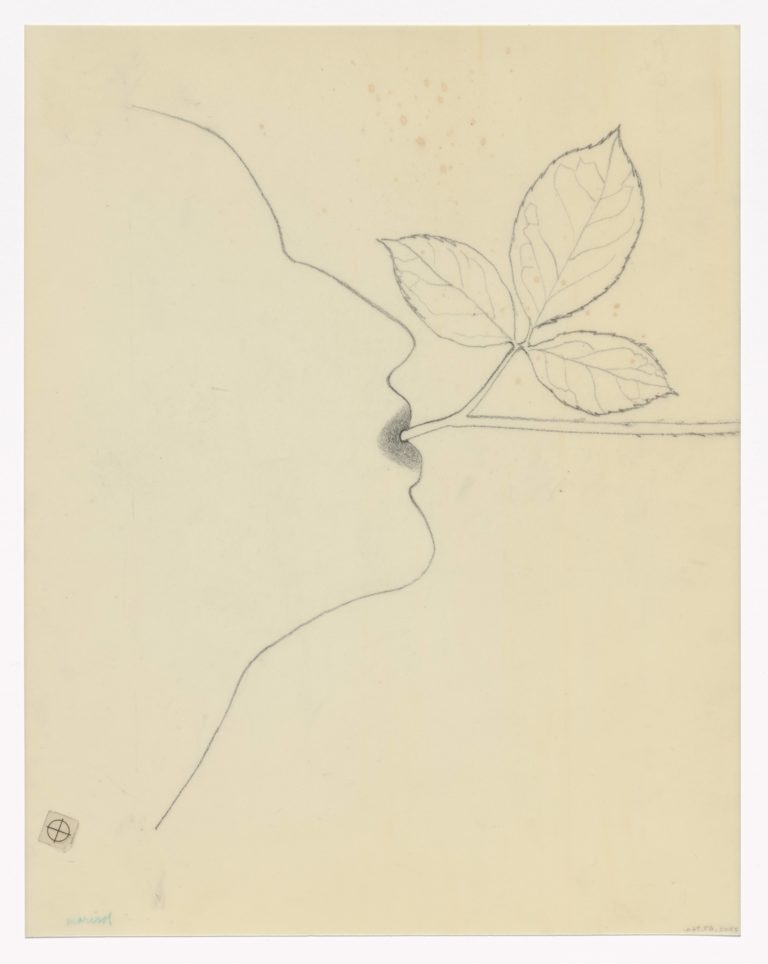

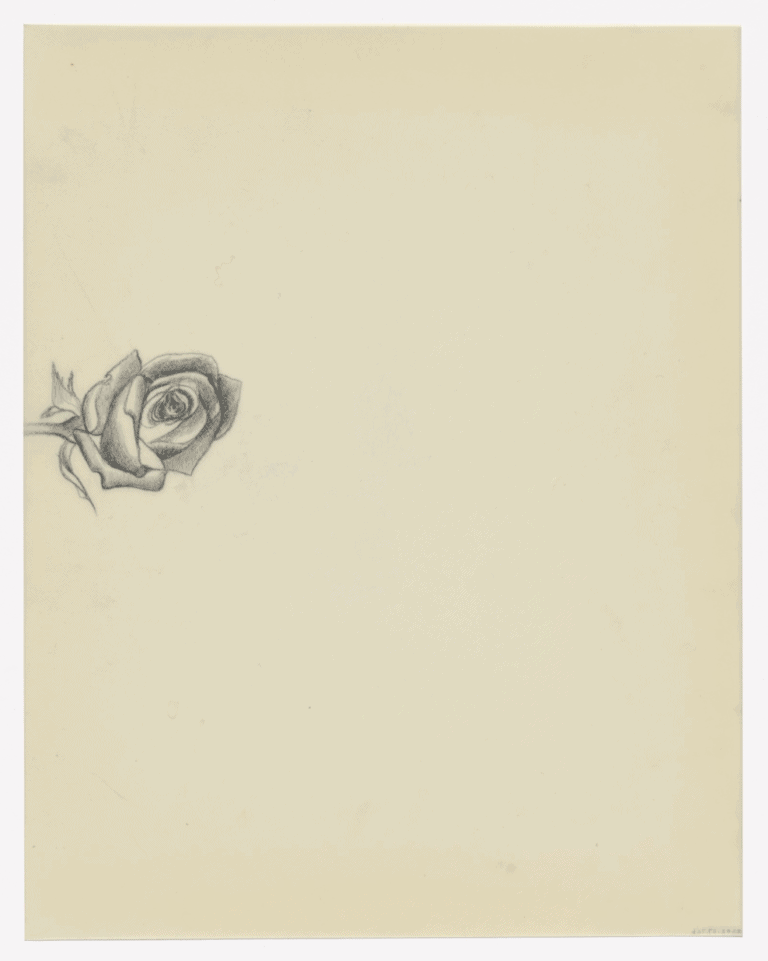

Marisol perhaps confirmed Love’s connection to O’Hara when she adapted the sculpture’s composition to serve as her elegiac ode to the poet upon his sudden, tragic death at age forty. Marisol was one of the thirty artists close to O’Hara invited to contribute to the memorial exhibition and publication Frank O’Hara/In Memory of My Feelings (MoMA, 1967).13While the volume’s editor, poet Bill Berkson, did not include “Having a Coke with You” in the 1967 MoMA publication, he would later incorporate it in an imagined revised list of “30 poems by Frank O’Hara as if chosen now for In Memory of My Feelings, MoMA, 1967.” See Bill Berkson, “A Frank O’Hara File,” in Lovers of My Orchards: Writers and Artists on Frank O’Hara, ed. Olivier Brossard (Montpellier: Presses universitaires de la Méditerraneé, 2017), 53–54. Each artist was assigned a poem, given the type pages, and encouraged to create any response they saw fit. To accompany the poem “Chez Jane,” Marisol revisited Love, but this time an androgynous mouth sprouts a single rose—perhaps alluding to the minimal floral decorations on the café tables at which O’Hara dined with friends and wrote his famous collection Lunch Poems (1964). Roses proliferate in O’Hara’s poetry, populating scenes about sensuality, violence, and the tragic brevity of the radiant, rollicking everyday (as invoked by the “sunset of roses” in “Chez Jane”). Marisol adapts funereal custom when she offers a rose to her lost friend. The flower perhaps extends from her own lips to tenderly overlap with O’Hara’s text, brightening into warm sepia once it reaches the page bearing his words. Or, the lips may be O’Hara’s, the source of blossoming poetry and vibrant conversation. If one rotates the drawing into a vertical composition (invited via the relationship to Love and typical floral positioning), Marisol envisions the poet in his grave, reaching up from the earth to sprout flowers and poetry. This rose may therefore symbolize interpersonal communication, an apt ode to her famously chatty, eloquent friend who sought to build a “poetry between two persons instead of two pages.”14Frank O’Hara, “Personism” (1959), in Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 498–99. Marisol, by contrast, assumed a persona whose silent detachment had reached mythic status. Indeed, she inverted the midcentury stereotype of the exuberant Latina just as O’Hara defied that of the stoic male. Marisol’s origin story for her taciturnity is grounded firmly in mourning, as the artist “decided never to talk again” at the age of eleven, the year she lost her mother to suicide.15Marina Pacini, “Marisol: A Biographical Sketch,” in Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper, exh. cat. (Memphis: Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, 2014), 12. When facing O’Hara’s death, at a time when words fail, she perhaps offered up a single rose as a muted stand-in for the lovingly earnest language that would befit and poignantly honor her convivial friend.

A third work—Marisol’s print Paris Review (1967)—cinches the connection between Love and her memorial drawing for O’Hara, serving as a transitional link between the two. The print translates Love into a flat graphic form and bears the same profile that appears in Frank O’Hara/In Memory of My Feelings (this time with bright pink lipstick offering a hyperfeminine contrast to the bald head).16The print has been exhibited twice at MoMA: in Word and Image: Posters and Typography from the Graphic Design Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, 1879–1967 (1968) and in The Modern Poster (1988). See relevant installation photographs here and here. In the latter photo, see Paris Review half obscured from view on the far left, mistakenly displayed in a vertical orientation likely due to its close connect to Love, which MoMA acquired in 1974. Marisol’s decision to employ this imagery for her Paris Review commission may even link to O’Hara. The elite literary magazine had rejected O’Hara’s poems during his lifetime, and Marisol’s print seems to not only mock the mandatory, thoughtless ingestion of the highbrow “must-read” but also call its nutritional value into question by packaging it as soda.17In 1968, after O’Hara’s death and with a new editor at the helm, Paris Review first published O’Hara’s work (a suite of nine poems). Marjorie Perloff, “Frank O’Hara and the Aesthetics of Attention,” boundary 2 4, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 781–82. Yet, ambiguous as ever, the print actually oscillates between depicting our sincere enthusiasm for flowing drinks/language and our pressured consumption of “the right” products/poetry to attain a desired life/erudition. Ultimately, this suite of works (sculpture, poem, drawing, and print) reveal Marisol and O’Hara charting alternative paths regarding intimacy, as they navigate capitalistic and literary-cultural landscapes.18I’m grateful to Katherine Brodbeck, Cathleen Chaffee, Kalliopi Minioudaki, and Susanna Temkin for sharing their astute insights regarding this Marisol-O’Hara dialogue.

- 1Tom Wesselmann purchased Love from the last Tanager Gallery group show in January 1962. See Irving Sandler, “Oral History Interview with Tom Wesselmann, 1984 January 3–February 8,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-tom-wesselmann-12439#transcript.

- 2

- 3Marisol and O’Hara became friends in the 1950s, circulating in the same New York social/cultural scenes and vacationing with an intimate cohort on Long Island during the summers. O’Hara mentions Marisol in his poem “Macaroni” (1961).

- 4In his non-manifesto “Personism” (1959), O’Hara proposes a mode of writing that generates “the illusion of intimate talk between I and you,” yet is at once “transparent and opaque . . . showing all but disclosing nothing . . . [T]he anticonfessional poet reveals all, only to reveal nothing about himself.” See Marjorie Perloff, Frank O’Hara: Poet Among Painters (New York: George Braziller, 1977), 26; and Terrell Scott Herring, “Frank O’Hara’s Open Closet,” PMLA 117, no. 3 (May 2002): 418.

- 5Sid Sachs, “Beyond the Surface: Women and Pop Art 1958–1968,” in Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958–1968, eds. Sid Sachs and Kalliopi Minioudaki (Philadelphia: University of the Arts, 2010), 34.

- 6For a brief discussion of other works by Marisol that “defy a normative heterosexual reading,” see Rachel Middleman, Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 2.

- 7José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 6, 9. In the introduction to this pivotal book, Muñoz articulates the potential for queer futurity through his discussion directly relating O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You” to a 1950s drawing by Warhol that depicts a Coke bottle with a single rose, an image that remarkably links the three works by Marisol examined in this essay.

- 8Jasper Bernes, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017), 43.

- 9Sachs, “Beyond the Surface,” 34.

- 10“70 Million Cokes a Day,” New York Times, October 23, 1962, 70.

- 11I discuss Marisol’s engagement with US–Latin American Cold War frictions in “Marisol’s Antimonument: Masculinity, Panamericanism, and Other Imaginaries,” Art Bulletin 102, no. 3 (Fall 2020): 104–29.

- 12Brad Gooch, City Poet:The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara (New York: Knopf, 1993), 346. Brian Glavey, “Having a Coke with You Is Even More Fun Than Ideology Critique,” PMLA 134, no. 5 (October 2019): 999.

- 13While the volume’s editor, poet Bill Berkson, did not include “Having a Coke with You” in the 1967 MoMA publication, he would later incorporate it in an imagined revised list of “30 poems by Frank O’Hara as if chosen now for In Memory of My Feelings, MoMA, 1967.” See Bill Berkson, “A Frank O’Hara File,” in Lovers of My Orchards: Writers and Artists on Frank O’Hara, ed. Olivier Brossard (Montpellier: Presses universitaires de la Méditerraneé, 2017), 53–54.

- 14Frank O’Hara, “Personism” (1959), in Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 498–99.

- 15Marina Pacini, “Marisol: A Biographical Sketch,” in Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper, exh. cat. (Memphis: Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, 2014), 12.

- 16The print has been exhibited twice at MoMA: in Word and Image: Posters and Typography from the Graphic Design Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, 1879–1967 (1968) and in The Modern Poster (1988). See relevant installation photographs here and here. In the latter photo, see Paris Review half obscured from view on the far left, mistakenly displayed in a vertical orientation likely due to its close connect to Love, which MoMA acquired in 1974.

- 17In 1968, after O’Hara’s death and with a new editor at the helm, Paris Review first published O’Hara’s work (a suite of nine poems). Marjorie Perloff, “Frank O’Hara and the Aesthetics of Attention,” boundary 2 4, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 781–82.

- 18I’m grateful to Katherine Brodbeck, Cathleen Chaffee, Kalliopi Minioudaki, and Susanna Temkin for sharing their astute insights regarding this Marisol-O’Hara dialogue.