In her detailed analysis of Heman Chong’s nearly two-decade-long artistic practice, art historian and curator Kathleen Ditzig contextualizes the ways in which Chong has consistently and intently negotiated with cultural policy and national politics. Ditzig builds on a 2013 essay, in which she posits the Singapore “state as meta-curator,” and argues for the individual curator’s agency in dispelling the myth of its omnipotence.1Kat Tan, “Definitions of the Artistic: State as Meta-Curator,” in A History of Curating in Singapore, exh. cat. (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2013). The editor sincerely thanks Jeannine Tang for this reference.

In 2011, Heman Chong (Singaporean, born 1977) predicted the future.2The author would like to thank Heman Chong, Wong Binghao, Jeannine Tang, Kenneth Tay, and Roger Nelson for their contributions to the development of this essay. Furthermore, the author would like to acknowledge the 2015 exhibition A Luxury We Cannot Afford, which was curated by Singaporean curator Lim Qinyi at Para Site, Hong Kong. The group exhibition, which featured Singaporean artists including Chong, posited that the Singaporean milieu produced a specific vein of critical artistic practice that was reactionary to the nation-state’s economic and political environment and the turn in the 1990s to policies that funded the arts. The exhibition title paraphrases a famous quote by former prime minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew that named the arts as a luxury the young nation could not afford. The ideas that emerge in this essay respond to such thinking around the entanglements of cultural production and political landscape.

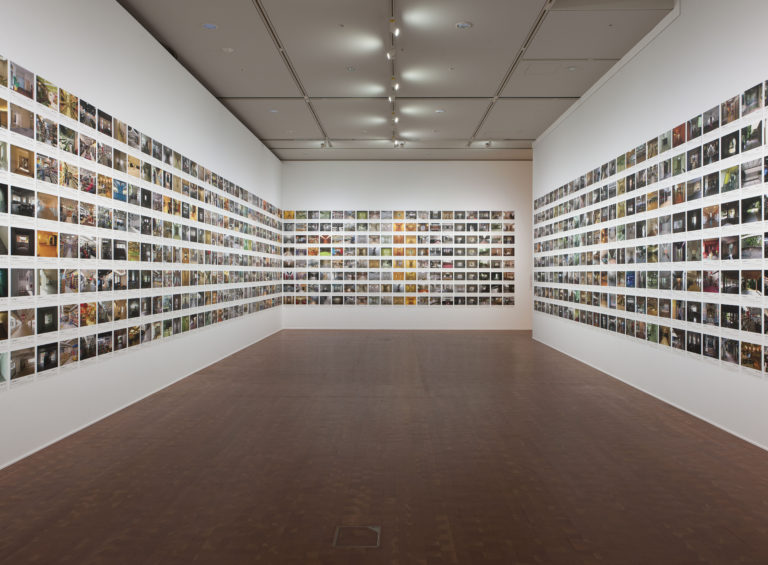

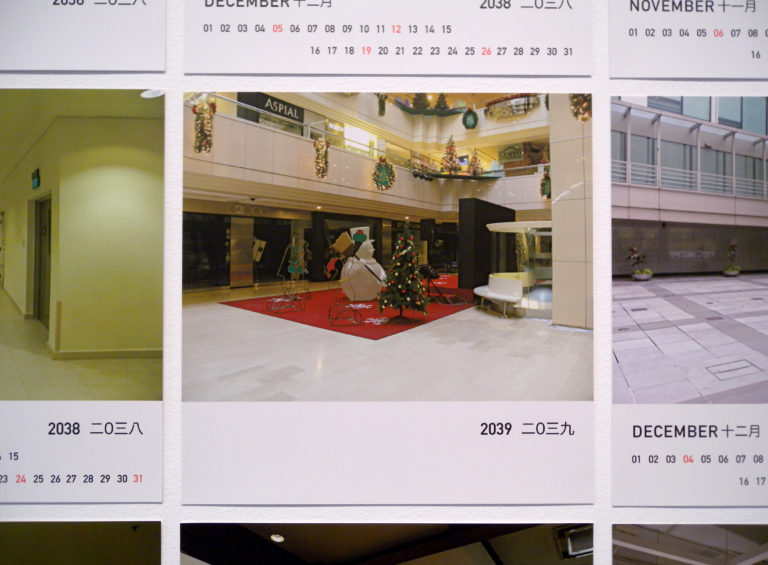

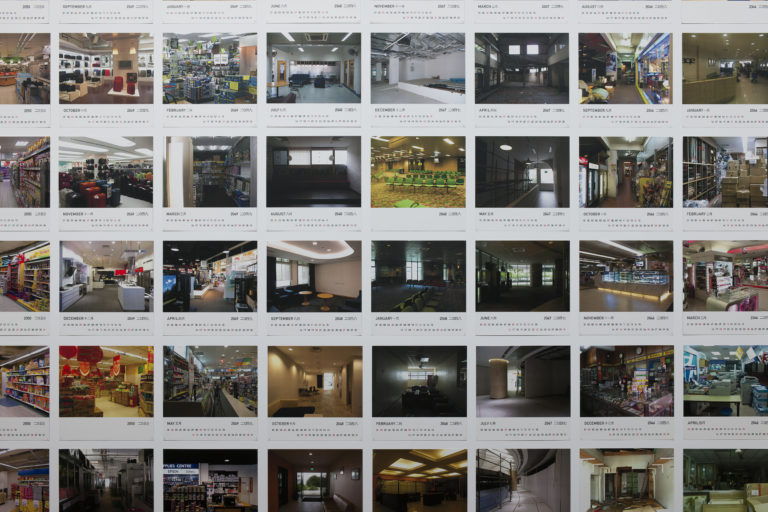

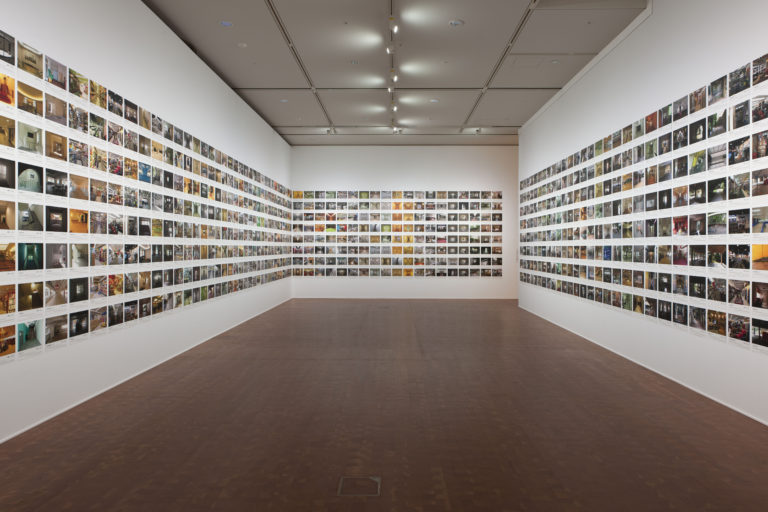

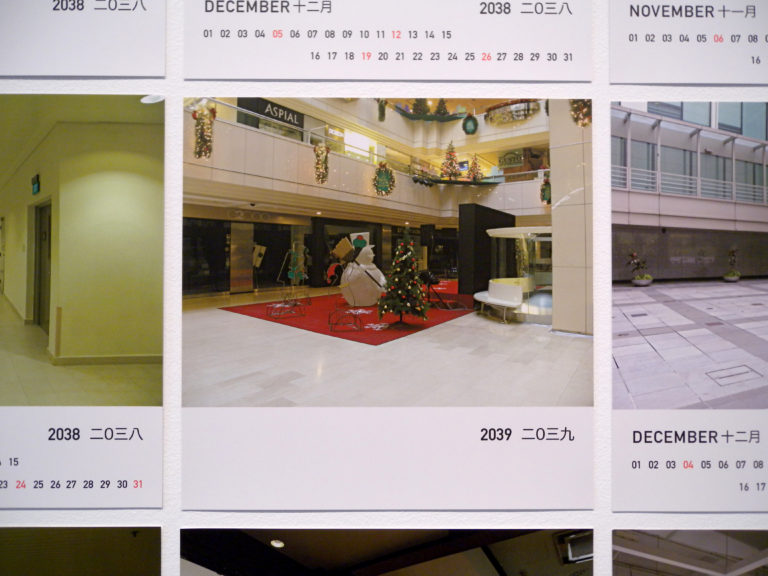

He debuted a work titled Calendars (2020–2096), a collection of 1,001 images of emptied–out void decks, IKEA showrooms, airport terminals, shopping centers—public spaces in Singapore devoid of people. From 2004 to 2010, Chong photographed spaces he described as “susceptible to change, to every sway of policy, to every new wave of capital”3Calendars (2020–2096), NUS Museum, Singapore, 2014, www.hemanchong.com/stuff/calendars2020-2096.pdf.—and by laying them out as a calendar that starts in January 2020 and runs through 2096, he used these images, each of which represents a month, to map the future onto the present and the past onto the future. Chong’s decision to start the calendars in 2020 was informed by his fascination with 2020 being “the year when all the problems in the world could possibly be solved,”4Ibid. and the inherent mix of disappointment and optimism of such an impossible promise.

Nine years after they were first exhibited, these images proved both prophetic and ironic as the COVID-19 pandemic emptied out public spaces and plunged the world into a year of government-mandated sheltering in place. Heman Chong had made pictures of a future no one could have predicted. Using the calendar format, Chong visualizes a circuiting of the past-present-future through a mechanism of accumulation. In projecting forward images of emptied public spaces, Chong prospects a potential future. I contend that in their ambiguity and open-endedness as banal everyday public spaces, these images hedge the future. They are hedges in terms of being deliberate strategies to systematically limit the risk of becoming irrelevant. Moreover, I contend that these hedges are an artistic strategy that arises out of Chong operating within Singapore’s system of authoritarian capitalism and his global awareness of conceptualism. Given that the histories of authoritarian capitalism and conceptualism arise out of the Cold War expansion of the American empire, these hedges offer a lens through which to consider post-conceptualism from Southeast Asia.

Hedging as Artistic Strategy in Heman Chong’s Work

The term “hedging” generally refers to a risk–management investment strategy undertaken to protect against loss. It can also mean the limiting or qualifying of something by conditions.5See “Hedging: Protection from financial risk,” Corporate Finance Institute website, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/hedging/; and Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, s.v. “hedge,” https://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/unabridged/hedge. In the context of this essay, I have both meanings in mind as I describe Chong’s practice. The open-endedness of the photographs in Calendars (2020–2096) and the appropriation of the calendar format to decontextualize the images into myriad possible futures, create a visual system and a hedge that ensures the work will always produce “new” meanings regardless of how the future plays out. In this sense, how Calendars (2020–2096) literally works is encapsulated in the complexity of its surface—in images of emptied–out public spaces as calendar pages.

Chong’s artworks can be read as both systems and strategies that mirror (and critique) the technocratic systems that define Singapore’s brand of capitalism. Chong has referred to this “surface complexity” as a key facet of his work.6Conversation with author, February 2021. The term is an oxymoron in that it refers to the work’s surface encapsulating the complexity of the work as a generative visual system. In the case of Calendars (2020–2096),the visual register of the calendar is the system, and the images of the emptied–out public spaces are the open-ended components of this system onto which various possible meanings can be ascribed. The images, and the system they embody, beg seductively to be overread. In this way, the surface of Chong’s work is a prime place in which indeterminacy can be managed toward the most “generative” ends.7Kenneth Tay, “Itinerant Futures,” in Of Indeterminate Time or Occurrence, exh. cat. (Singapore: FOST Gallery, 2014). The point is not that Chong predicts future events like COVID-19—Calendars (2020–2096) is a visualization of a long game: its imagistic system will always predict something—but rather that he manages the indeterminacy of the future.

This form of hedging, or the systematic management of indeterminacy, is an allegory of the larger meta strategies endemic to the Singapore state.8For a more detailed argument of how Chong’s work can be read as opened systems that are inspired by Singapore’s own everyday systems, see Kathleen Ditzig, “Peace Prosperity and Friendship with All Nations,” in Heman Chong: Peace Prosperity and Friendship with All Nations, exh. cat. (Singapore: Singapore Tyler Print Institute, 2021). Chong’s choice of subject matter directly points to Singapore’s land management and lauded public housing program, a technocratic system of “hedging” on the future that structures much of life on the island. The nation’s housing program is a form of land management in which land is transformed into public and private spaces and, in turn, into assets. The sale of homes directly contributes to the state’s income. At the same time, the value of those homes is protected from unbridled speculation. The funding of mortgages for public housing through social security savings in particular has been described as “a closed circuit of financial transaction between the Housing Development Board (HDB) and the social security savings boards, the Central Provident Fund (CPF), established in 1955.”9Chua Beng Huat, Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017), 78, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt1zkjz35. Integral to Singapore’s governance, capital from the CPF is used to purchase government bonds for national development programs and is the foundation of the Government Investment Corporation (GIC), Singapore’s first sovereign wealth fund for global investments.10The Singapore government regularly monitors and reviews the overall long-term performance of and risk profile for the nation’s reserves, managed by GIC, MAS (the central bank), and Temasek Holdings. See Ravi Menon, “How Singapore Manages Its Reserves” (transcript of keynote speech, National Asset-Liability Management Europe Conference, March 13, 2019), https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/speeches/2019/how-singapore-manages-its-reserves. This capital has prevented the Singaporean government from becoming dependent on international financial agencies like the World Bank, unlike many other states in Southeast Asia, and has enabled Singapore to become one of the richest countries in the world.11However, this is not only an economic measure but also a political one. In 2018, 91 percent of Singaporeans owned homes. As Chua Beng Huat has noted, all but rich Singaporeans have “no choice but to avail themselves of public housing. This total dependency on the state for a very important necessity of life has turned the citizens into clients of the state, thereby reducing very substantially the political space for citizens to negotiate with the government. It has instead enabled the government to embed different social policies—ranging from discipling labor to governing family and race as the conditions of eligibility for public housing on a captive citizenry.” Chua, Liberalism Disavowed, 82. It is a networked system of capital accumulation based on forecasting and the realities of operating as an island-nation in an international marketplace. Hedging, understood broadly (and according to the expanded definition used in this essay) within this system, is a strategy of national interest that manages risk by structuring the national system to always be generative and by using any surplus in an international market. In turn, the national system/market is protected from the volatility of the international market.

In a report for ArtAsiaPacific, Chong links his conceptual practice to the material conditions of working within Singapore’s authoritarian capitalism:

“I have always argued that every piece of art produced is embodied in a larger political reality, and that much of what we do as artists in Singapore is linked to our country’s own political realities. As such, all art is political, no matter how much we want to distance ourselves from that fact. How then can I, as an artist, influence these sets of political realities? I am not interested in being a politician, but in many ways there are more possibilities in Singapore for an artist to work politically than for an actual politician. . . . I feel strongly that the answers might lie in the resources that we have in Singapore: namely, an incredibly strong economy that allows for a large budget surplus every year, which, in turn, is channeled in part to art and cultural activities and institutions. As an artist, I have access to these funds, and it is relatively easy for me to come up with art projects that do not involve any form of object-making. I can use this money to organize workshops or informal residencies, all under the guise of an art project. This, of course, is nothing new and I’m not the first to think of this.”12Heman Chong, “A Country, At Large,” ArtAsiaPacific, no. 98 (May/June 2016), artasiapacific.com/Magazine/98/ACountryAtLarge.

Chong’s “hedges” are artistic strategies that arise from his experience of operating out of Singapore’s authoritarian capitalism, as it fits within larger global systems and histories of capitalism. In a transparent yet totalizing technocratic system of governance, one has to be able to read between the lines that exist in the public sphere to perceive the underlying operations at play. An individual’s agency comes from navigating these systems and manipulating the material byproducts of the system—literally working through and with the surfaces of meta governing systems. In Calendars (2020–2096), one is compelled to read into emptied-out spaces in order to “see” the system at work as it extrapolates into the future, but it is this very compulsion to “read into” that is generative and enables a speculative system that allows Calendars (2020–2096) to “predict” the future.

The Politics of Art and Authoritarian Capitalism

In 2015, the popular Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek published an essay titled “Capitalism Has Broken Free of the Shackles of Democracy,” an ode as it were to Singapore’s brand of capitalism.13Slavoj Zizek, “Capitalism Has Broken Free of the Shackles of Democracy,” Financial Times, February 1, 2015, www.ft.com/content/088ee78e-7597-11e4-a1a9-00144feabdc0. Zizek opens the essay with a prediction that one day the world will build monuments to Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding prime minister, as the creator of authoritarian capitalism.

This ideology, Zizek claims, is “set to shape the next century as much as democracy shaped the last.”Ibid. Seeming to fulfill this projection, Singapore has been the national development goal of the likes of Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s president, who once stated that he hoped his country would become “the Singapore of Africa.”14“How Foreigners Misunderstand Singapore,” Economist, June 1, 2017, www.economist.com/asia/2017/06/01/how-foreigners-misunderstand-singapore. This sentiment has been echoed by vocal Brexiteers who dream of turning Britain into “Singapore-on-Thames,” as well as by American Republicans who want an American healthcare system modeled on Singapore’s.15Ibid Moreover, authoritarian capitalism, since the publication of Zizek’s essay and with the increasing anxiety over China’s rise, has gained currency.16Zizek cites Deng Xiao Peng’s study of Singapore as informing this notion. More recently, President Joe Biden’s first address to Congress threw the stakes of this shift into sharp relief when he said, “It is clear, absolutely clear . . . that this is a battle between the utility of democracies in the 21st century and autocracies.” Commentators in turn have noted that “China is arguing that their brand of authoritarian capitalism is predictable and produces prosperity, whereas the American model is socially divisive, politically unpredictable, and economically reckless.” See Alex Ward, “Joe Biden Wants to Prove Democracy Works—Before It’s Too Late, Vox, April 28, 2021, https://www.vox.com/2021/4/28/22408735/joe-biden-congress-speech-democracy-autocracy. For earlier references, see Niv Horesh, “The Growing Appeal of China’s Model of Authoritarian Capitalism, and How It Threatens the West,” South China Morning Post, July 19, 2015, https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1840920/growing-appeal-chinas-model-authoritarian-capitalism-and-how; John Lee, “Western vs. Authoritarian Capitalism,” Diplomat, June 18, 2009, https://thediplomat.com/2009/06/western-vs-authoritarian-capitalism/; and Kevin Rudd, “The Rise of Authoritarian Capitalism, New York Times, September 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/16/opinion/politics/kevin-rudd-authoritarian-capitalism.html. Yet, even as it found its way into President Joe Biden’s first congressional address, authoritarian capitalism is difficult to define. There are many different and unique forms of authoritarian capitalism. In this regard, it should not be a read as a derogatory term. What the term essentially refers to is a system in which the presence of a capitalist economy exists alongside the absence or erosion of civil liberties.17Daniel Kinderman, “Authoritarian Capitalism and Its Impact on Business” (paper presented at the Symposium on Authoritarianism and Good Governance, International Institute of Islamic Thought, February 2021, http://doi.org/10.47816/02.001.23.

Zizek and other intellectuals have noted that authoritarian capitalism has increasingly become the norm rather than the exception.18In fact, Richard Carney, in his recent study of the international growth of Sovereign Wealth Funds and state-owned enterprises, notes that since the end of the Cold War, there has been a rise of “dominant-party authoritarian regimes” such that they constitute one-third of all regimes in the world. See Richard D. Carney, Authoritarian Capitalism: Sovereign Wealth Funds and State-Owned Enterprises in East Asia and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 6. Yet for the most part, this material historical reality has not been considered within art world discourses or in the art historical examination of post-conceptual practices like Chong’s, which are products of, as much as responses to, these operating systems. In this regard, much has been made of the Singapore state’s censorship, and yet much less attention has been given to thinking about the kind of cultural landscape and society that is produced by this brand of authoritarianism.19For a larger global analysis of the rise of this brand of capitalism, see Peter Bloom, Authoritarian Capitalism in the Age of Globalization (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Press, 2016).

According to data from 2016, up to 85 percent of Singapore’s art scene is funded by the state.20Nile Bowie, “Singapore Swings and Misses at the Arts,” Asia Times, February 10, 2018, asiatimes.com/2018/02/singapore-swings-misses-arts/. Richard Carney’s in-depth study of Singapore’s authoritarian capitalism illustrates how the prevalence of state-owned enterprises is part of the ruling party’s capacity to stay in power.21Richard D. Carney, Authoritarian Capitalism: Sovereign Wealth Funds and State-Owned Enterprises in East Asia and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 1. This extends to the island’s cultural landscape and is most evident in Singapore’s Visual Arts Cluster, a strategic leadership body that consists of the National Gallery Singapore and Singapore Art Museum, museums of modern and contemporary art respectively, and the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI). This centralization of resources transparently ties together the public and private spheres, whose alignment can benefit the ecology of Singapore contemporary art. Arguably the country’s most successful and well-networked commercial art gallery, STPI is itself a government limited company.22The Visual Arts Cluster (VAC) is also representative of the “conglomeration” that can happen under state capitalism. The VAC, established in 2013, is a recent development. It is indicative of the types of systems and opportunities that define Singapore’s ecology—an ecology catalyzed by cultural “creative city” policies of the late 1990s and early 2000s, namely the Renaissance City Plans of 1999–2008, which were spurred by the economic recession of 1985. For a survey of Singapore’s cultural policy, see Lily Kong, “Ambitions of a Global City: Arts, Culture and Creative Economy in ‘Post-Crisis’ Singapore,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 18, no. 3 (January 31, 2012): 279–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2011.639876. Artists like Chong thus develop their practices in a system in which the public and private spheres are, to a degree, centrally “regulated,” if not centrally “aligned.”

Considering how this has informed his artistic practice, Chong wrote in a feature on the Singapore art scene in 2018:

“Looking back, my entire journey as an artist has been heavily assisted by cultural policies, which have produced the institutions that have served as cornerstones in the evolution of my practice. . . . Since 1999, Singapore’s National Arts Council (NAC) has supplied me with grants to participate in art fairs, biennials, conferences, exhibitions and residencies abroad, enabling me to build a network that allows me access to even more of these art events and festivals. The Substation, an independent art space founded in 1990 by the late theatre doyen Kuo Pao Kun, was the first building funded by the NAC’s Arts Housing Scheme and was also the first place where I showed my work. There, I tested out many of the ideas behind my subsequent exhibitions. The NAC is also commissioner of the Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where I was invited to represent my country at the 50th edition in 2003. The list goes on.”23Chong, “A Country, At Large.”

Chong’s development as an artist is entangled in the acceleration of the state’s investment in contemporary art.24Alexie Glass and Andrew Maerkle, “You Have Reached Domestic. How Can I Assist You Today?,” ArtAsiaPacific, no. 60 (September 2008), artasiapacific.com/Magazine/60/YouHaveReachedDomesticHowCanIAssistYouTodayHemanChong. Between 2000 and 2002, with one of the first bursaries from the NAC, Chong studied at the Royal College of Art in London, earning a master’s degree in Communication Art and Design. Shortly after, then Singapore Art Museum (SAM) curator Ahmad Mashadi selected Chong’s video installation Molotov Cocktails (Grey Aquarium Remix) (1999) to represent the country at the 10th India Triennale 2001, where it was one of nine works awarded a jury prize. After receiving his master’s, Chong was the first Singaporean artist selected for a one-year residency (2002–3) at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien (KB), again with the support of the NAC. Also in 2003, at the age of twenty-five, he was one of three artists to present work in the 2nd Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Beyond the litany of achievements enabled by the state, the KB residency facilitated a turning point in Chong’s practice. In Berlin, Chong was introduced to an international network of contemporary art and artists, whose discourses and agents would become elements in his practice as he began to operationalize systems beyond those within Singapore. As a testament to his success in doing this, in 2005, as part of its promotion of the 3rd Singapore Pavilion, the NAC commissioned him to organize the pavilion’s opening party at the Palazzo Pisani Moretta. Chong’s savvy, flexibility, and ambition are not just characteristic of a global neoliberal creative class, but also the defining attributes of his capable navigation of Singapore’s authoritarian capitalism.

However, despite this, Chong should not be mistaken for a lackey of the state or a dilettante of the international art world. After moving to Berlin, he shifted his focus from the cinematic to the conceptual, and more specifically, to an interrogation of Western conceptualism. This interrogation paralleled Chong’s development of a reflexive language that spoke to power. In 2004, he organized his own solo exhibition Snore Louder If You Can at the Substation. In an accompanying statement, he describes the works in the exhibition as a series of ideas about negotiating access and authority:

“I have always been fascinated by how a person is allowed or rejected into a space or a situation based on specific criteria of authoritarians, e.g., club bouncers, art jurors, electronic ticketing gates at train stations—and along the lines of this concept . . . I have generally appropriated concepts and styles from conceptualism and minimalism, and it is this strain that I wish to expand on in my work; an endless reworking of ideas inherited from the transmission of other works from exhibitions (real experience) and information (represented experience), in order to see how the works could stand the strain of being copied and realigned, creating different meanings in their forms.”25Heman Chong, “Snore Louder If You Can: A Solo Exhibition by Heman Chong,” http://biotechnics.org/1hemanchong_snorelouderifyoucan.html.

This extrapolation of conceptual art strategies to speak intelligently to overarching governing contemporary systems that order human life is perhaps no more apparent than in Chong’s Monument to the people we’ve conveniently forgotten (I hate you) (2008), an expansive installation of one million blacked–out business cards that, when installed, expand into a sea of shimmering black, taking over floors of an exhibition space or bursting forth from a closet, in effect intervening and remaking the architecture of the exhibition space and how people engage with it. The work recalls some of the prominent strategies employed by Felix Gonzalez-Torres (American, born Cuba, 1957–1996) in his emotive installations of luminous candy spills or stacks of imprinted paper, which themselves recall the work of Carl Andre (American, born 1935) and Donald Judd (American, 1928–1994).26See, for example, the following work: Felix Gonzales-Torres. “Untitled” (Public Opinion), 1991. Black rod licorice candies individually wrapped in cellophane, endless supply, dimensions variable, ideal weight: 700 lbs. (317.5 kg). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Purchased with funds contributed by the Louis and Bessie Adler Foundation, Inc., and the National Endowment for the Arts Museum Purchase Program, 1991. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/1512.

Incidentally conceived during, but not inspired by, the global financial crisis of 2008, the blacked–out business cards can be read as analogous to the ensuing economic devastation and subsequent fundamental restructuring of the world. The one million cards point to a disposable connection or business identity, to the lost and forgotten opportunities that effectively colonize the spaces that they occupy, and could be subconsciously inspired by, the crisis of confidence in the neoliberal capitalist system that was triggered by the 2008 financial crisis.27Timothy C. Earle, “Trust, Confidence, and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis,” Risk Analysis 29, no. 6 (2009), onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01230.x.

In many ways, Chong’s works are successful because they respond and adapt to material conditions of the systems that govern the making of a work and its travel. His blacked–out business cards, for example, accumulate into a dark, tidal mass that viewers have to push through with their feet. Each step upon the cards is deliberate if you do not want to fall. The gallery sitter holds his breath as he watches you, and agonizes over when he should intervene to mitigate the museum’s risk of an accident. Chong re-disciplines viewers’ bodies and social relations through his disproportionate extrapolation of the scale of the blacked-out business cards. He is astutely aware of the material parameters and affects that govern how we navigate the world.

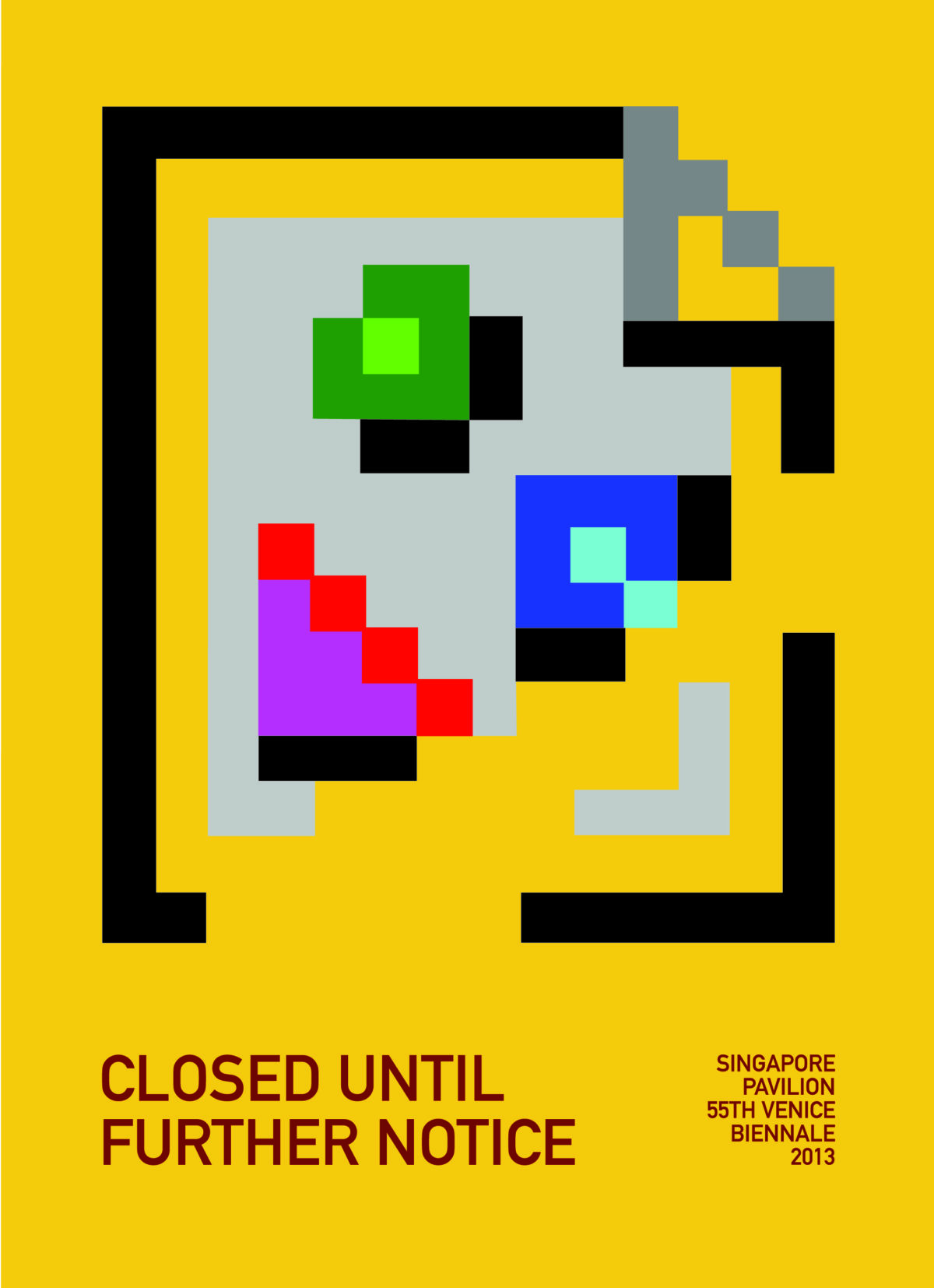

In this sense, the politics of Chong’s work are real and make themselves known in material ways. This was especially evident when he leveraged the opportunities presented by Singapore’s authoritarian capitalist system and operationalized his art world networks as deft critiques. In 2012, the National Arts Council of Singapore—in perhaps the most post-colonial and yet ill-conceived move it has made in its lifespan—decided to withdraw Singapore from the Venice Biennale.28Brittney, “Singapore to Return to Venice Biennale in 2015,” Art Radar Journal, April 8, 2013, https://artradarjournal.com/2013/04/08/singaporean-to-return-to-venice-biennale-in-2015/. Gillman Barracks, a designated arts cluster, was scheduled to open that year alongside other initiatives. It could, therefore, be argued that 2013 was the year that Singapore needed to flex on an international stage. Chong, with Ho Rui An, a younger Singaporean artist, authored a public petition to call for the return of the Singapore Pavilion. Leveraging his international network, Chong created CLOSED UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE (SINGAPORE PAVILION / 55TH VENICE BIENNALE / 2013), an image of a broken file link, which he published in an issue of AsiaArtPacific magazine as an advertisement, bringing a largely provincial protest into regional discourse. The image of a broken link spoke not only to how there had been a breakdown in the marketing of Singapore but also to how art is a system of information, an idea that he had articulated in 2004.29Chong, “Snore Louder If You Can.” In 2013, then Minister of Community, Culture, and Youth Lawrence Wong announced that Singapore would return to the Venice Biennale and went so far as to commit to the long-term lease of a pavilion within the Arsenale.30Lawrence Wong, “Doing More to Develop Our Own Singaporean Contemporary Artists,” MCCY [Ministry of Culture, Community, and Youth], April 24, 2014, https://www.mccy.gov.sg/about-us/news-and-resources/speeches/2014/apr/medium-at-large-exhibition-launch.

Post-Conceptualism: Histories of an Authoritarian Future

There is more to the cloth of conceptualism that Chong wears. The artistic strategies that he employs not only speak to the political-economic systems he navigates, but also reflect upon the duplicitous history of Western conceptualism itself. Chong’s painting practice, for example, grew out of Cover Versions (2009– ),an ongoing work comprised of paintings of book covers based on recommendations from friends. For the last eleven years, Chong has engaged in a daily ritual of painting on the same-size canvas with the same brand of commercially produced paint. This practice recalls a similar one by On Kawara (Japanese, 1933–2014), an artist whose legacy, along with that of others, like Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Chong has inherited, making his own artistic practice fundamentally post-conceptual.31Conversation between Heman Chong and Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, 2016, www.johanlundh.net/heman-chong/.

Each of Kawara’s date paintings, otherwise known as his “Today” series, straightforwardly notes the date of its making on a monochromatic ground of gray, red, or blue. Each painting was developed through a series of steps that never varied and that were inspired by the conventions of recording the date of the place in which it was made. However, often forgotten in discussions of Kawara’s date paintings is that, as part of the artwork, the artist fabricated a cardboard box in which to store each work. Some of the boxes are lined with cuttings from the front page of the local newspaper.32“Paintings: Today Series/Date Paintings,” Guggenheim Museums and Foundation website, www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/on-kawara-silence/paintings-today-series-date-paintings?gallery=onkawara_date_paintings. Interestingly, the series grew out of a triptych self-referentially titled Title, which consists of paintings that spell out, in sequential order, “One Thing,” “1965,” and “Viet-Nam.33”Melissa Ho, “American Art and the Vietnam War,” Smithsonian American Art Museum website, posted March 14, 2019, americanart.si.edu/blog/american-art-and-vietnam-war. The monumentalizing of the small and specific events in Kawara’s date paintings is inseparable from the procedural accumulation of artistic labor reflected in the objects. Yet the roots of this practice are tied to a conflict in Southeast Asia that would rattle the Cold War convictions held in the West.

In channeling the legacies of Kawara’s conceptualism, Chong’s post-conceptual practice implicitly speaks to the twofold relationship between international histories of conceptualism and authoritarian capitalism. Lucy Lippard’s canonical definition of conceptual art, in relation to the American context, the dematerialization of the art object, and the democratization of the art world, as “the era of the Civil Rights Movement, of Vietnam, the Women’s Liberation Movement and the counter-culture,” has often been used as a historical reference in aligning post-conceptualism.34Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972; A Cross-Reference Book of Information on Some Esthetic Boundaries (New York: Praeger, 1973), vii. Marked by the “art of everyday life,” the trajectory of conceptualism in the West took the artwork out of the gallery and into the street, enfolding it in the larger social fabric.35Tahl Kaminer, Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation: The Reproduction of Post-Fordism in Late-Twentieth-Century Architecture (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011), 118. (This book was temporarily loaned from Heman Chong’s and Renee Staal’s The Library of Unread Books when it was presented at I_s_l_a_n_d_s Peninsula at Excelsior Shopping Centre in Singapore from October 2 to October 25, 2020.) However, alongside these developments in the West, certain strains of conceptualism in Southeast Asia became embedded in authoritarian regimes placed in power by the United States during the Cold War.36See Marian Roces, Rustom Bharucha, and Elena Mirano, Gathering: Political Writing on Art and Culture (Singapore: NUS Press, 2020), 303, for the relationship between dictatorships and conceptualism. For other texts that address the different trends of conceptualism, see Apinan Poshyananda, “‘Con Art’ Seen from the Edge: The Meaning of Conceptual Art in South and Southeast Asia,” in Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s, exh. cat. (New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999); and T. K. Sabapathy, “Reading Conceptual Art in Southeast Asia: A Beginning,” in Charting Thoughts Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, eds. Sze Wee Low and Patrick D. Flores (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 237–39. Sabapathy delineates two waves of conceptual art—in the 1970s as a regional phenomenon and in the 1990s as an international phenomenon.

During the Cold War, authoritarianism was seen as a necessary evil to limit the expansion of Soviet influence and further projects of decolonialization.37For a broader, in-depth examination of decolonialization, see Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020). For studies of American support of authoritarian regimes, see Osita G. Afoaku, “U.S. Foreign Policy and Authoritarian Regimes: Change and Continuity in International Clientelism,” Journal of Third World Studies 17, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 13–40, www.jstor.org/stable/45198191. It was believed, at the time, that in order to have agency on the international stage and a place alongside Western states, domestic political struggles and contestations had to be contained.38James Baldwin, “Princes and Power,” in Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985 (New York: St Martin’s, 1985), 59. Richard Wright, one of the most influential African American writers of the time argued at the 1956 Congress of Black Writers in Paris that “dictatorial methods” and the use of “personal power” were necessary to hasten the “social revolution.” Marian Pastor Roces, in her essay “Conceptual Art, Authoritarianism, 1970s, Asia,” notes that in this historical milieu, conceptual art offers the possibility of hidden or coded messages, but could also be mere “window dressing for fascism,”39Roces, Bharucha, and Mirano, Gathering,303: “On the American Flank of the Cold War were dictators who traded heavily in cultural capital. Aside from Iran’s Shah, King Hassan II of Morocco also staged the 1970s performing and visual artist-luminaries in Rabat and his other courts. The performers included some of the global avant-garde who might have been expected to address their critical eye at the ideological contexts of their tours in dictators’ turfs. Taking their turns at authoritarian social engineering King Hassan II and Mohammad Reza Shah were like their contemporary Ferdinand Marcos proxies for the interests of the Euro-American hand of the world. All three, as well as the autocrats Anastasio Somoza Debayle [and his father and brother before him] of Nicaragua and Augusto Pinochet of Chile, were preserved in place for decades by American military, economic and cultural power.” as in the case of the first two directors of the Cultural Center of the Philippines.40The Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) was established in 1969. Conceptual art emerged at the CCP, whose first two directors, Roberto Chabet and Raymundo R. Albano, were canonical conceptual artists. Albano would remain the organization’s director until 1985. While Roces does not directly refer to Singapore in her text, the historical and geopolitical milieu that she paints of the Cold War is one that informs Singapore’s history as a nation-state.41See Wen-Qing Ngoei, “Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore Bloomed in the Shadow of the Cold War,” Diplomat, March 28, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/03/lee-kuan-yews-singapore-bloomed-in-the-shadow-of-the-cold-war/; and Wen-Qing Ngoei, Arc of Containment: Britain, the United States, and Anticommunism in Southeast Asia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019).

While different threads of conceptualism evolved alongside and in different ways from authoritarian regimes around the world, the West’s discourse on conceptualism in the 1980s and 1990s expanded the understanding that art need not be aesthetic, freeing up what might constitute artistic material, or what Rosalind Krauss has called the “post medium.”42See Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000). “Post-conceptual art,” an extension of this trajectory, is a term that, coined by Peter Osborne, refers to an expanded art practice blending art practices from performance to installation to painting.43Peter Osborne, “Contemporary art is post-conceptual art” (transcript of public lecture, Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Villa Scuota, Como, July 9, 2010), https://silo.tips/download/contemporary-art-is-post-conceptual-art. Although it has since been defined in a number of different ways, the key tenets of post-conceptual art are its ahistoricity, a condition of high capitalism, and its double-coded nature as both conceptual and aesthetic in form.44Peter Osborne, “The Postconceptual Condition: Or, the Cultural Logic of High Capitalism Today,” Radical Philosophy, no. 184 (March/April 2014), https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/the-postconceptual-condition. As such, post-conceptualism cannot be understood through a linear chronology of post-1960s art movements. As Osborne describes, “It denotes an art premised on the complex historical experience and critical legacy of conceptual art, broadly construed in such a way as to register the fundamental mutation of the ontology of the artwork carried by that legacy.”45Ibid. The term has been used by Singaporean intellectuals such as C. J. Wee Wan-Ling in relation to contemporary aspects of Singapore’s condition of rapid modernization.46C. J. Wan-Ling Wee, “The Singapore Contemporary and Contemporary Art in Singapore,” in Low and Flores, Charting Thoughts, 252–54.

Chong’s post-conceptual practice can be described through either Osborne’s or Wee’s definition. Yet, these readings of post-conceptualism do not address the significance of Chong’s claimed inheritance of conceptualism and the situated histories of authoritarian capitalism from which his practice has developed.47Heman Chong’s practice is not the only form of post-conceptualism that conforms to these definitions and yet also speaks to the complex historical trajectories they engage. You may find similar tendencies in the work of other Southeast Asian artists, including Sung Tieu and Pio Abad, but such an examination is beyond the scope of this paper. From the cultural value of a painting to a business card and an advertisement in a magazine, Chong occupies the systems and material codifications of our world, and then mobilizes, contorts, distorts, and ultimately explodes these systems from within. The hedges in Chong’s work—the systematic operationalizing of the surface of the artwork—are subversive and duplicitous. They are generous in artistic affinities and yet deftly mercantile in insuring their relevance.

With the pressures of COVID-19 and our reliance on global platform technologies promising to exponentially feed the growth of authoritarian capitalism as a world-system, it is this unpoetic language of the hedge, a facet of Chong’s practice located at the intersection of the Janus-faced histories of global conceptualism and authoritarian capitalism, that speaks directly to a politic of the future that has long since arrived.

- 1Kat Tan, “Definitions of the Artistic: State as Meta-Curator,” in A History of Curating in Singapore, exh. cat. (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2013). The editor sincerely thanks Jeannine Tang for this reference.

- 2The author would like to thank Heman Chong, Wong Binghao, Jeannine Tang, Kenneth Tay, and Roger Nelson for their contributions to the development of this essay. Furthermore, the author would like to acknowledge the 2015 exhibition A Luxury We Cannot Afford, which was curated by Singaporean curator Lim Qinyi at Para Site, Hong Kong. The group exhibition, which featured Singaporean artists including Chong, posited that the Singaporean milieu produced a specific vein of critical artistic practice that was reactionary to the nation-state’s economic and political environment and the turn in the 1990s to policies that funded the arts. The exhibition title paraphrases a famous quote by former prime minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew that named the arts as a luxury the young nation could not afford. The ideas that emerge in this essay respond to such thinking around the entanglements of cultural production and political landscape.

- 3Calendars (2020–2096), NUS Museum, Singapore, 2014, www.hemanchong.com/stuff/calendars2020-2096.pdf.

- 4Ibid.

- 5See “Hedging: Protection from financial risk,” Corporate Finance Institute website, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/hedging/; and Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, s.v. “hedge,” https://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/unabridged/hedge.

- 6Conversation with author, February 2021.

- 7Kenneth Tay, “Itinerant Futures,” in Of Indeterminate Time or Occurrence, exh. cat. (Singapore: FOST Gallery, 2014).

- 8For a more detailed argument of how Chong’s work can be read as opened systems that are inspired by Singapore’s own everyday systems, see Kathleen Ditzig, “Peace Prosperity and Friendship with All Nations,” in Heman Chong: Peace Prosperity and Friendship with All Nations, exh. cat. (Singapore: Singapore Tyler Print Institute, 2021).

- 9Chua Beng Huat, Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017), 78, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt1zkjz35.

- 10The Singapore government regularly monitors and reviews the overall long-term performance of and risk profile for the nation’s reserves, managed by GIC, MAS (the central bank), and Temasek Holdings. See Ravi Menon, “How Singapore Manages Its Reserves” (transcript of keynote speech, National Asset-Liability Management Europe Conference, March 13, 2019), https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/speeches/2019/how-singapore-manages-its-reserves.

- 11However, this is not only an economic measure but also a political one. In 2018, 91 percent of Singaporeans owned homes. As Chua Beng Huat has noted, all but rich Singaporeans have “no choice but to avail themselves of public housing. This total dependency on the state for a very important necessity of life has turned the citizens into clients of the state, thereby reducing very substantially the political space for citizens to negotiate with the government. It has instead enabled the government to embed different social policies—ranging from discipling labor to governing family and race as the conditions of eligibility for public housing on a captive citizenry.” Chua, Liberalism Disavowed, 82.

- 12Heman Chong, “A Country, At Large,” ArtAsiaPacific, no. 98 (May/June 2016), artasiapacific.com/Magazine/98/ACountryAtLarge.

- 13Slavoj Zizek, “Capitalism Has Broken Free of the Shackles of Democracy,” Financial Times, February 1, 2015, www.ft.com/content/088ee78e-7597-11e4-a1a9-00144feabdc0.

- 14“How Foreigners Misunderstand Singapore,” Economist, June 1, 2017, www.economist.com/asia/2017/06/01/how-foreigners-misunderstand-singapore.

- 15Ibid

- 16Zizek cites Deng Xiao Peng’s study of Singapore as informing this notion. More recently, President Joe Biden’s first address to Congress threw the stakes of this shift into sharp relief when he said, “It is clear, absolutely clear . . . that this is a battle between the utility of democracies in the 21st century and autocracies.” Commentators in turn have noted that “China is arguing that their brand of authoritarian capitalism is predictable and produces prosperity, whereas the American model is socially divisive, politically unpredictable, and economically reckless.” See Alex Ward, “Joe Biden Wants to Prove Democracy Works—Before It’s Too Late, Vox, April 28, 2021, https://www.vox.com/2021/4/28/22408735/joe-biden-congress-speech-democracy-autocracy. For earlier references, see Niv Horesh, “The Growing Appeal of China’s Model of Authoritarian Capitalism, and How It Threatens the West,” South China Morning Post, July 19, 2015, https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1840920/growing-appeal-chinas-model-authoritarian-capitalism-and-how; John Lee, “Western vs. Authoritarian Capitalism,” Diplomat, June 18, 2009, https://thediplomat.com/2009/06/western-vs-authoritarian-capitalism/; and Kevin Rudd, “The Rise of Authoritarian Capitalism, New York Times, September 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/16/opinion/politics/kevin-rudd-authoritarian-capitalism.html.

- 17Daniel Kinderman, “Authoritarian Capitalism and Its Impact on Business” (paper presented at the Symposium on Authoritarianism and Good Governance, International Institute of Islamic Thought, February 2021, http://doi.org/10.47816/02.001.23.

- 18In fact, Richard Carney, in his recent study of the international growth of Sovereign Wealth Funds and state-owned enterprises, notes that since the end of the Cold War, there has been a rise of “dominant-party authoritarian regimes” such that they constitute one-third of all regimes in the world. See Richard D. Carney, Authoritarian Capitalism: Sovereign Wealth Funds and State-Owned Enterprises in East Asia and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 6.

- 19For a larger global analysis of the rise of this brand of capitalism, see Peter Bloom, Authoritarian Capitalism in the Age of Globalization (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Press, 2016).

- 20Nile Bowie, “Singapore Swings and Misses at the Arts,” Asia Times, February 10, 2018, asiatimes.com/2018/02/singapore-swings-misses-arts/.

- 21Richard D. Carney, Authoritarian Capitalism: Sovereign Wealth Funds and State-Owned Enterprises in East Asia and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 1.

- 22The Visual Arts Cluster (VAC) is also representative of the “conglomeration” that can happen under state capitalism. The VAC, established in 2013, is a recent development. It is indicative of the types of systems and opportunities that define Singapore’s ecology—an ecology catalyzed by cultural “creative city” policies of the late 1990s and early 2000s, namely the Renaissance City Plans of 1999–2008, which were spurred by the economic recession of 1985. For a survey of Singapore’s cultural policy, see Lily Kong, “Ambitions of a Global City: Arts, Culture and Creative Economy in ‘Post-Crisis’ Singapore,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 18, no. 3 (January 31, 2012): 279–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2011.639876.

- 23Chong, “A Country, At Large.”

- 24Alexie Glass and Andrew Maerkle, “You Have Reached Domestic. How Can I Assist You Today?,” ArtAsiaPacific, no. 60 (September 2008), artasiapacific.com/Magazine/60/YouHaveReachedDomesticHowCanIAssistYouTodayHemanChong.

- 25Heman Chong, “Snore Louder If You Can: A Solo Exhibition by Heman Chong,” http://biotechnics.org/1hemanchong_snorelouderifyoucan.html.

- 26See, for example, the following work: Felix Gonzales-Torres. “Untitled” (Public Opinion), 1991. Black rod licorice candies individually wrapped in cellophane, endless supply, dimensions variable, ideal weight: 700 lbs. (317.5 kg). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Purchased with funds contributed by the Louis and Bessie Adler Foundation, Inc., and the National Endowment for the Arts Museum Purchase Program, 1991. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/1512.

- 27Timothy C. Earle, “Trust, Confidence, and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis,” Risk Analysis 29, no. 6 (2009), onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01230.x.

- 28Brittney, “Singapore to Return to Venice Biennale in 2015,” Art Radar Journal, April 8, 2013, https://artradarjournal.com/2013/04/08/singaporean-to-return-to-venice-biennale-in-2015/.

- 29Chong, “Snore Louder If You Can.”

- 30Lawrence Wong, “Doing More to Develop Our Own Singaporean Contemporary Artists,” MCCY [Ministry of Culture, Community, and Youth], April 24, 2014, https://www.mccy.gov.sg/about-us/news-and-resources/speeches/2014/apr/medium-at-large-exhibition-launch.

- 31Conversation between Heman Chong and Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, 2016, www.johanlundh.net/heman-chong/.

- 32“Paintings: Today Series/Date Paintings,” Guggenheim Museums and Foundation website, www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/on-kawara-silence/paintings-today-series-date-paintings?gallery=onkawara_date_paintings.

- 33”Melissa Ho, “American Art and the Vietnam War,” Smithsonian American Art Museum website, posted March 14, 2019, americanart.si.edu/blog/american-art-and-vietnam-war.

- 34Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972; A Cross-Reference Book of Information on Some Esthetic Boundaries (New York: Praeger, 1973), vii.

- 35Tahl Kaminer, Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation: The Reproduction of Post-Fordism in Late-Twentieth-Century Architecture (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011), 118. (This book was temporarily loaned from Heman Chong’s and Renee Staal’s The Library of Unread Books when it was presented at I_s_l_a_n_d_s Peninsula at Excelsior Shopping Centre in Singapore from October 2 to October 25, 2020.)

- 36See Marian Roces, Rustom Bharucha, and Elena Mirano, Gathering: Political Writing on Art and Culture (Singapore: NUS Press, 2020), 303, for the relationship between dictatorships and conceptualism. For other texts that address the different trends of conceptualism, see Apinan Poshyananda, “‘Con Art’ Seen from the Edge: The Meaning of Conceptual Art in South and Southeast Asia,” in Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s, exh. cat. (New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999); and T. K. Sabapathy, “Reading Conceptual Art in Southeast Asia: A Beginning,” in Charting Thoughts Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, eds. Sze Wee Low and Patrick D. Flores (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 237–39. Sabapathy delineates two waves of conceptual art—in the 1970s as a regional phenomenon and in the 1990s as an international phenomenon.

- 37For a broader, in-depth examination of decolonialization, see Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020). For studies of American support of authoritarian regimes, see Osita G. Afoaku, “U.S. Foreign Policy and Authoritarian Regimes: Change and Continuity in International Clientelism,” Journal of Third World Studies 17, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 13–40, www.jstor.org/stable/45198191.

- 38James Baldwin, “Princes and Power,” in Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985 (New York: St Martin’s, 1985), 59. Richard Wright, one of the most influential African American writers of the time argued at the 1956 Congress of Black Writers in Paris that “dictatorial methods” and the use of “personal power” were necessary to hasten the “social revolution.”

- 39Roces, Bharucha, and Mirano, Gathering,303: “On the American Flank of the Cold War were dictators who traded heavily in cultural capital. Aside from Iran’s Shah, King Hassan II of Morocco also staged the 1970s performing and visual artist-luminaries in Rabat and his other courts. The performers included some of the global avant-garde who might have been expected to address their critical eye at the ideological contexts of their tours in dictators’ turfs. Taking their turns at authoritarian social engineering King Hassan II and Mohammad Reza Shah were like their contemporary Ferdinand Marcos proxies for the interests of the Euro-American hand of the world. All three, as well as the autocrats Anastasio Somoza Debayle [and his father and brother before him] of Nicaragua and Augusto Pinochet of Chile, were preserved in place for decades by American military, economic and cultural power.”

- 40The Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) was established in 1969. Conceptual art emerged at the CCP, whose first two directors, Roberto Chabet and Raymundo R. Albano, were canonical conceptual artists. Albano would remain the organization’s director until 1985.

- 41See Wen-Qing Ngoei, “Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore Bloomed in the Shadow of the Cold War,” Diplomat, March 28, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/03/lee-kuan-yews-singapore-bloomed-in-the-shadow-of-the-cold-war/; and Wen-Qing Ngoei, Arc of Containment: Britain, the United States, and Anticommunism in Southeast Asia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019).

- 42See Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

- 43Peter Osborne, “Contemporary art is post-conceptual art” (transcript of public lecture, Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Villa Scuota, Como, July 9, 2010), https://silo.tips/download/contemporary-art-is-post-conceptual-art.

- 44Peter Osborne, “The Postconceptual Condition: Or, the Cultural Logic of High Capitalism Today,” Radical Philosophy, no. 184 (March/April 2014), https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/the-postconceptual-condition.

- 45Ibid.

- 46C. J. Wan-Ling Wee, “The Singapore Contemporary and Contemporary Art in Singapore,” in Low and Flores, Charting Thoughts, 252–54.

- 47Heman Chong’s practice is not the only form of post-conceptualism that conforms to these definitions and yet also speaks to the complex historical trajectories they engage. You may find similar tendencies in the work of other Southeast Asian artists, including Sung Tieu and Pio Abad, but such an examination is beyond the scope of this paper.