Art historian Anissa Rahadiningtyas triangulates feminism, environmentalism, and Islam in her treatise on Arahmaiani’s long-term, performative, and community-based work Proyek Bendera (Flag Project), proposing that this trinity of socio-political causes in the Indonesian artist’s work can cultivate a reparative and egalitarian space of potential.

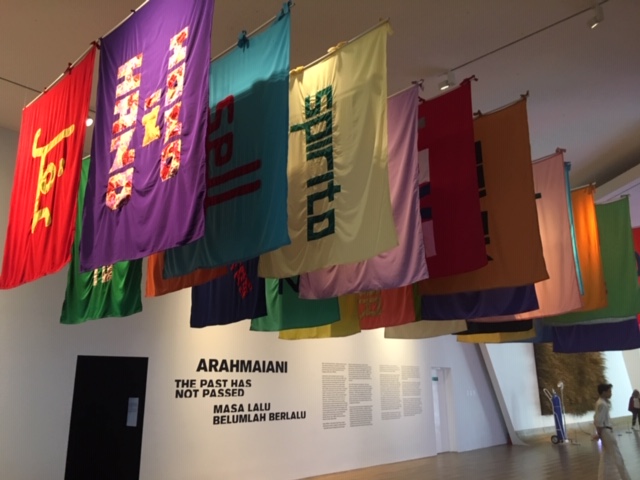

In many of the ongoing collaborative projects undertaken by Arahmaiani (Indonesian, born 1961), environmentalism remains at the center and is inextricably entangled with concerns about global Islam and feminism. Proyek Bendera (Flag Project), a nomadic, community-based project started in 2006, perhaps manifests most strongly Arahmaiani’s commitment to environmental issues. Proyek Bendera is a series of site-specific performances incorporating colorful flags with words stitched onto them—a visual and creative manifestation of the artist’s collaborative work with different communities in Yogyakarta, Germany, Singapore, Japan, and Tibet (to name a few) to address social, political, religious, and environmental issues. In this project, stitching words onto colorful flags is a way for Arahmaiani to express the voices and agency of marginalized groups and to channel notions of power, pride, and a sense of belonging.1Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author via WhatsApp, June 2021. In many iterations of Proyek Bendera, Arahmaiani works closely with local communities to conceptualize and discuss ideas and visions based on particular problems that they face and to materialize them onto the flags, which are then used in related collaborative performances. Proyek Bendera communicates Arahmaiani’s commitment to engage in transcultural and interreligious dialogues between the Muslim world and the rest of the world that often intersect with environmental concerns.2Arahmaiani, Artist’s Statement, Flag Project, Yogyakarta, September 1, 2010. This document was shared with the author by the artist. The collaborative work behind Proyek Bendera in Yogyakarta in 2010 with the communities of artists and santri (students at a pesantren or Qur’anic school) at Pesantren Amumarta and Pesantren Budaya Kaliopak and with the monks and residents of the village of Lab in Tibet from 2010 onward, perhaps best showcases Arahmaiani’s invitation to reparation—a way to redress the tangled issues surrounding the image of Islam, marginalization of women and other religious/ethnic groups, and environmental challenges.

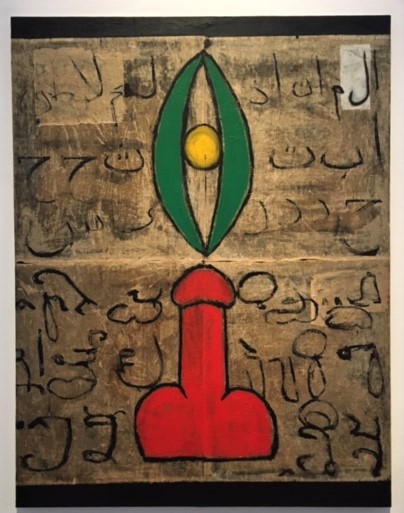

Arahmaiani’s nomadic life began early in her artistic career. Since the time she was a student in the late 1970s and 1980s, her collaborative performances have often been critical of the violence perpetrated by the dictatorial regime of the New Order under General Soeharto (1967–98). In 1994, Arahmaiani’s solo exhibition in Jakarta titled Sex, Coca-Cola, and Religion elicited an unprecedented reactionary response from a group of Muslim audience members who denounced her painting Lingga-Yoni (1993) and the installation titled Etalase as blasphemous. The reactionary Muslim group condemned Arahmaiani for juxtaposing Arabic script with what they deemed profane images and so issued death threats that forced her to flee Indonesia to Australia, where she decided to teach at a private art school and continue her studies. Since then, she has worked and exhibited internationally in the Netherlands, Thailand, and several other places. I identify the underlying shift toward an increased Islamic orthodoxy during the New Order period as the precondition to this reactionary response and the more conservative expressions of Islam in Indonesian social and political lives. When Arahmaiani was forced to leave her home, the experience of not being tethered became inherent to her artistic practice. Being a nomad allows her to work in different sites, to share her concerns and artmaking practices more broadly, and to actively collaborate with diverse communities. I perceive that for Arahmaiani, being a nomad challenges a sense of fixity and boundedness, allowing her to explore the multiple origins and circulations of pre-Islamic and Islamic practices—from Java to Tibet to India—that continue to shape her convictions and ideas of being Muslim.

Fig. 3. Arahmaiani. Lingga-Yoni. 1993. Acrylic and rice paper on canvas, 71 5/8 x 55 1/8 in. (182 x 140 cm). Installation view, Arahmaiani: The Past Has Not Passed, Museum MACAN (Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara), Jakarta, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

Arahmaiani’s reputation and active participation in global contemporary art exhibitions since the 1990s, and her intense focus on social and political issues that impact women, have put her at the front and center of research and publications on contemporary art from the Global South. Exhibitions, reviews, and scholarly undertakings have justifiably positioned her works among other feminist projects in the secular development of modern and contemporary art in Indonesia and Asia.3See for example, Amanda Rath, “Contextualizing Contemporary Art: Propositions of Critical Artistic Practice in Seni Rupa Kontemporer in Indonesia” (PhD diss., Cornell University, 2011), 285–325; and Wulan Dirgantoro, “Arahmaiani: Challenging the Status Quo,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context, and Enquiry 42 (Autumn/Winter, 2016): 24–35. In this article, I seek to frame my analysis of Arahmaiani’s collaborative works with pesantren in Yogyakarta and the Buddhist monastery in Tibet within the contexts of feminist struggles in the decolonized world and of reparation and interreligious environmentalism. A recent article by Edwin Jurriëns attempts to locate Arahmaiani’s works within the performative frameworks and practices of unjuk rasa and ekofeminisme by focusing on similar projects that Arahmaiani conducted in Yogyakarta in 2006 and Tibet in 2010.4Edwin Jurriëns, “Gendering the Environmental Artivism: Ekofeminisme and Unjuk Rasa of Arahmaiani’s Art,” Southeast Asia of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 4, no. 2 (October 2020): 3–38. Jurriëns utilizes the concept of unjuk rasa as tied closely to ekofeminisme to highlight the performative and political aspects of Arahmaiani’s works and connect them to broader ecofeminist activism in Indonesia. He expands the meaning of “unjuk rasa,” which in its common usage loosely translates as “protest” or “demonstration,” to capture the multisensory engagement and creativity inherent in its practice. Unjuk rasa, Jurriëns further iterates, is a creative and critical exploration and expression of sensory politics that shape the actor’s feelings, knowledge, and self-perception. Jurriëns decides to use the Indonesian transliteration and translation of the discourse of ecofeminism “to mark the local inflections of interpretations and practices of the concept.”5Ibid., 12. Jurriëns specifically discusses how the women- and farmers-led activism and resistance against the state’s mining project, which threatens the ecology and livelihood of the people in the Kendeng mountain area in Central Java, is interconnected (albeit indirectly) to Arahmaiani’s artistic and activist practice.6See ibid., 11–14. This short article complements Jurriëns’s analysis and framework of ekofeminisme in Arahmaiani’s collaborative, community-based work by considering the role of religion and religious institutions in disseminating and putting into practice local knowledge and history related to the environment and environmentalism.

Scholars have extended the framework of “reparation” and “reparative feminism” in postcolonial and feminist studies beyond the concern of racial slavery in European and US contexts.7See Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–51. Drawing from the works of feminist scholars, Joshua Chambers-Letson notes that various feminist, queer, and postcolonial projects have always been inherently reparative.8Joshua Chambers-Letson, “Reparative Feminisms, Repairing Feminism—Reparation, Postcolonial Violence, and Feminism,” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 16, no. 2 (July 2006): 176–77. Chambers-Letson continues by asserting that reparation is a way to address the historical injury and violence by coming to terms with the past “as a means of putting together, at least enough to be able to move into the future and possibility of love.”9Ibid., 173. Seeking the possibility of love in relation to the injuries of our pasts and presents, which are affected by colonialism, decolonization, and global capitalism, seems to be the underlying determination in Arahmaiani’s works and activism as shown in Proyek Bendera and her collaborative works in Java and Tibet.10Arahmaiani’s commitments and choice of materiality in her iterations of Proyek Bendera (Flag Project)also draw from her collaborative works in Bangkok, where she worked together with the local Muslim and silk-weaving community of Baan Krua. The project is titled Stitching the Wound and the exhibition was held at the Art Center at the Jim Thompson Art House in Bangkok. In this project, Arahmaiani also made use of and presented Jawi scripts in addition to working with local women and young girls to generate a creative dialogue manifested in their performance during the opening of the exhibition.

Born in Bandung in 1961, Arahmaiani is representative of a generation of young artists in the late 1970s and 1980s whose works were shaped by the need for a new art praxis to accompany an equally newfound political awareness and activism against the increasingly authoritarian and oppressive rule of the New Order regime. This generation of artists addressed the limitations of the male-centered, politically neutral, and disinterested modernist practice in Indonesia through new media art and performance works. Thus, performance and installation became Arahmaiani’s mediums of political and environmental activism, through which she progressively articulates the importance of collaboration as a strategy of reparation. Arahmaiani’s works from 2006 onward seek to show the experience and reality of Muslims and women actively contributing to shaping the image of global Islam. As Arahmaiani suggests, her collaborative method opens her artmaking practice to be “participative and active [and so] involving everyone who sees it and joins it in building a foundation for a more open, democratic, equal, and tolerant society.”11Arahmaiani, Artist’s Statement, quoted in publication material for the iteration of the Flag Project at Kayu Lucie Fontaine Bali, April 27–May 31, 2019.

Proyek Bendera and Environmental Projects

Proyek Bendera began in 2006 when Arahmaiani collaborated with communities of artists and santri at Pesantren Amumarta in Bantul, Yogyakarta, after a volcanic earthquake from the Mount Merapi eruption devastated the area. The project originally started as a response to the marginalized position of women in social, political, and religious spheres,12Arahmaiani and Siobhan Campbell, “Balancing Feminine and Masculine Energy,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 3, no. 1 (March 2019): 206. which has been one of Arahmaiani’s central themes. There is a notable difference in how gender is experienced in male-dominated spaces like pesantrens and monasteries. While Arahmaiani commanded respect from santris in the pesantren, she experienced cultural limitations in how she could engage with or address the community, and among the monks in Tibet, she learned that gender does not factor largely as lives reincarnate into different forms in the Buddhist belief system. Though there is a marked division of labor, especially in domestic spaces, many community projects in Tibet are done inclusively by monks and villagers of all genders. However, in Buddhism (especially in early interpretations of Buddhist texts), similar to other major religions, women practitioners often occupy a less prominent position than the male authorities. In response to women’s reduced role in major organized religions, Arahmaiani’s method as an artist embodies the position of women as mediums to the supernatural, a function that persists in certain societies in Southeast Asia.13See Barbara Watson Andaya, The Flaming Womb: Repositioning Women in Early Modern Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006). Arahmaiani sees her role as an artist as one of mediumship, albeit not with the otherworldly realm, and her performances as a kind of healing ritual.14Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author, March 2018.

Video documentation of Proyek Bendera, directed by Arahmaiani and her collaborators in different parts of the world, can be found on several free video-streaming platforms, allowing for broader circulation of her works outside of museums and other elite institutional settings.15My experience with and analysis of the many iterations of Arahmaiani’s Proyek Bendera is mediated by these videos and photo documentation in addition to Arahmaiani’s accounts, which I gathered through informal interviews and vernacular archives that the artist has shared with me since 2018. The video titled Crossing Point (2011), for example, opens with a scenic shot of Mount Merapi, one of the world’s most active volcanoes in Java, followed by scenes of the destruction left by the deadly 2010 eruption. This iteration of Proyek Bendera is part of the series in which Arahmaiani uses Jawi writing on the flags to carry messages and visions related to issues faced by the communities.16While Arahmaiani used Jawi writings in several previous iterations of Proyek Bendera, she only used it exclusively in 2010. For example, Arahmaiani’s I LOVE YOU installation and performance of Proyek Bendera at Esplanade in Singapore in 2009 displayed Jawi on one of the flags that Arahmaiani carried, but other flags contained words in different languages written in various scripts, including Latin and Chinese. The somber atmosphere of the scene is accompanied by the piercing, melodious vocalization of tembang (classical vocal music in the Javanese and Sundanese tradition) in a typical Javanese style, accompanied only by the sound of the wind blowing through the devastated landscape. The melodious tembang might serve as a cultural signifier, but it also has ties to Arahmaiani’s memory and experience of a local healing method.17Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author, May 2021. Arahmaiani shared her story of undergoing a healing ritual in Bali and told me that she remembered listening to tembang during the process. The idea and practice of healing are also manifest in Arahmaiani’s works. She sees her performances as healing rituals that nurture connectivity between individuals, communities, and nature.18Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author, March 2018. The video moves to capture the performance of Proyek Bendera, where Arahmaiani and her collaborators stand in the foreground of burned and fallen trees and wave the colorful flags. The Jawi words on the flags suggest notions of the impermanence of the physical world (such as ماوت = “death” in Arabic) and the importance of the sense of belonging, love, and local knowledge and wisdom (as seen in the words اوماہ = “omah” or “home” in Javanese; ترسنا = “tresna” or “love” in Balinese/Javanese; جنانا = “jnana” or “wisdom/knowledge” in Sanskrit). Jawi, also known as arab pegon/gundul in Javanese, is a permutation of Arabic script that was used in many parts of Islamic Southeast Asia to write and circulate knowledge in local languages before it was largely replaced by Latin script, which was introduced through the colonial education system, and subsequently pushed to the margins of modernity. Stitching the Jawi words onto the colorful flags serves to alleviate the tense relationship many Muslims in Indonesia have with Arabic script and to situate the writing outside the domain of religious expression. At the same time, Arahmaiani’s restitution of Jawi script in Proyek Bendera and many of her other installations and performances calls attention to the localized practices of Islam and experiences of being Muslim that are particular to the Indo-Malay Archipelago. Furthermore, using Jawi to articulate concerns, hopes, local wisdom, and visions of the communities serves to carry out a reparative project for the harmful image of Islam circulated in global (read: Western) media and extend the transcultural dialogue with the rest of the world.19Ibid.

Arahmaiani initially worked with a group of volunteers to help survivors and to rebuild the impacted area, including the pesantren. During this process, she met with the leader of Pesantren Amumarta, Kyai Djawis Masruri,20Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021. Kyai is an honorific title for an Islamic religious scholar or teacher. with whom she engaged in conversations regarding environmental issues and natural disasters. Pesantren Amumarta is perhaps one of the leading eco-pesantrens in Indonesia, and it is not surprising that environmental agendas are taken up institutionally in pesantrens as they have had a long history of leading agrarian communities across Sumatra and Java since at least the Dutch colonial period.21Anna M. Gade, Muslim Environmentalisms: Religious and Social Foundations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 66. In addition to teaching the santris about environmental issues, Arahmaiani gradually proposed several environmental initiatives, such as planting trees and encouraging organic farming to mitigate the impacts of natural disasters and climate change and to prevent a “hell” on earth.22Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021. While Kyai Djawis agreed on the importance of planting trees and organic farming, the lack of funding and support from governmental agencies prompted the pesantren to pursue more profitable programs. Through ongoing negotiations and conversations with the santris and local communities and inspired by a Quranic verse, the pesantren decided to develop a renewable energy production project using a local fruit called nyamplung (Calophylum inophyllum), and to work with local farmers as a cooperative to produce the biofuel.23Ibid. See also Kristina Großmann and Arahmaiani Feisal, “Islam-inspired Renewable Energy,” Inside Indonesia 133 (July–September 2018): 2–3. Despite Pesantren Amumarta’s commitment, Großmann and Arahmaiani observed in 2018 how the initiative stagnated as the biofuel failed to draw local government’s patronage (largely due to the lack of seriousness on the part of the local and national governments in battling environmental issues) and could hardly compete with the government’s fossil fuel subsidy. Today, Pesantren Amumarta continues to sustain its ecological programs by developing environmentally friendly products, such as natural dyes for batiks and organic cosmetic products. Moreover, Arahmaiani informed me that Pesantren Amumarta has recently considered embarking on a tree-planting program in the area.24Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021. While Arahmaiani’s work with Pesantren Amumarta focuses more on environmental issues, her collaboration with santris at Pesantren Budaya Kaliopak emphasizes cultural activism aimed at communicating the value of religious diversity and pluralism at the same time it fosters discussions about environmental challenges. I want to note that it is precisely this cultural and environmental activism at the grassroots level that constitutes the core of Arahmaiani’s many collaborative performances in Proyek Bendera. The same grassroots and community-based project that shows concerns for interfaith environmentalism is also the basis of her Proyek Bendera performance in Tibet.

Arahmaiani often jokingly discusses her experience in Tibet as being kesasar, which translates as a state of being lost, astray, or deviating from the expected course.25Arahmaiani, interview by Jaya Suprana, Jaya Suprana Show, streamed live on January 19, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hmGMVwQAwUw. Her initial visit to Tibet in 2010 came about through an invitation from the Museum of Contemporary Art Shanghai to continue her Proyek Bendera there. To the curators, Jim Supangkat and Biljana Ciric, Arahmaiani proposed to work with local communities within Chinese borders, seeking to engage with either a marginalized group or those impacted by natural disasters. Arahmaiani’s assistant, Li Mu, suggested visiting Tibet since the area had suffered an earthquake. Bringing her experience of working with communities impacted by natural disasters in Yogyakarta with her, Arahmaiani visited the heavily impacted area of Khamp, where she subsequently developed a good relationship with the monks of the Gelugpa (Yellow Hat) order at the Lab Monastery led by Kadheng Rinpoche and Geshe Sonam Lobsang. The Gelugpa order is the dominant school in Tibetan Buddhism, and the Dalai Lama is its most influential figure. Through conversations about environmental challenges with monks and villagers, and informed by the significance of the Plateau of Tibet as the water source for major rivers in Asia, Arahmaiani developed several environmental programs: waste management, reforestation, river water management for everyday use and energy source, organic farming, revitalization of nomadism, hydro-energy production, and solar panel systemization.26Arahmaiani and Campbell, “Balancing Feminine and Masculine Energy,” 211–12. Known as the “water tower of Asia” the Tibetan Plateau is the source of water for major river lines that go through Asia, providing water to more than two million people across South, East, and Southeast Asia. In its first five years,27Much of Arahmaiani’s environmental activism involving local communities does not seem to have a specific timeline for completion. Her work in Tibet is ongoing as she intends to return to Tibet when the COVID 19 pandemic is properly handled and countries reopen. She also maintains communication with the pesantrens and other communities she worked with in the past. the program received the support of the head monk and villagers from sixteen different villages, and in 2015, the collaborative effort received official support from the Chinese government, as many of its programs fit into the government’s green policies.28Arahmaiani and Campbell, “Balancing Feminine and Masculine Energy,” 211. Arahmaiani’s collaboration with the monks in Tibet has not only yielded sustainable environmental programs and transcultural exchanges as seen in Proyek Bendera, but also spurred her research interest in pre-Islamic beliefs and cultural systems and connections between Indonesia, nusantara,29Historically the term nusantara refers to geographical areas that were once under the tributary rule of the Majapahit empire, the last Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Java. The areas included many parts of maritime Southeast Asia, including the modern-day Indonesian archipelago, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and Southern Philippines. The term itself remains relevant in today’s Indonesia, denoting the whole island of Indonesia, and is a part of the national and cultural identity. Tibet, and India. This interest manifests in other works by Arahmaiani, including in the continuation of Proyek Bendera titled Proyek Bendera Nusantara (since 2010), and in a series of performances titled Shadows of the Past, in which she reenacts the performative elements with the flag in Proyek Bendera (see fig. 6). I would also argue that Arahmaiani’s collaboration with the monks of the Gelugpa order and communities from sixteen villages in the area achieve ecological reparation and food and resources sovereignty that reveal different levels of subtle resistance to the state’s oppressive and neoliberal policies.30Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021. Arahmaiani disclosed to me her observation of the reliance of the community in Tibet on the (unhealthy) food supplies imported from mainland China. While she was cautious to not frame her work in Tibet as political, it is not a stretch to see the food import as a way to exert control over the population in Tibet. For this reason, the ability to achieve resources sovereignty through local production of (healthier) foods and water management could serve as a mode of subtle resistance.

Reframing Environmental Urgencies in Interreligious Environmentalism

Regarding these collaborations with pesantrens and the monastery, I want to note the ways in which Arahmaiani translates and reframes environmental urgencies into multiple religious frameworks. Her proposal to the pesantrens and the conversations about environmental practices by Muslim actors often refer to Qur’anic messages and localized Islamic worldviews. In the Islamic ecotheological context, Arahmaiani’s sense of urgency when proposing her environmental measures to Pesantren Amumarta to mitigate natural disasters and prevent a “hell” on earth reflects the prominence of the eschatological dimensions of the Qur’an’s messages related to environmental justice issues.31Gade, Muslim Environmentalisms, 110–13. Anna Gade argues for the continued relevance of Qur’anic messages on eschatology (“last things”) in shaping the Islamic commitment to environmentalism.32Ibid., 3. Throughout the book, Gade argues the importance of acknowledging and emphasizing the prominent eschatological dimensions of Qur’anic messages in order to understand Muslim environmentalism and Islam. In the beginning of her book, she suggests, “Fundamental teachings on eschatology (‘last things’) seem as ethically relevant today as in the seventh century; so it is valid to generalize that Islamic commitments to the phenomenal world, so-called environmentalisms, would similarly address head-on the notion of responsible and human existence as that of being among other creatures in the face of the imminent potential for earth’s destruction.” Emphasis original. Kyai Djawis’s use of the fruits from nyamplung trees as a source of biofuel was inspired by a Qur’anic verse that tells believers to ignite a fire from a green tree and from stories told to him during his childhood about how fruits from local trees were used for lamp oil.33Großmann and Feisal, “Islam-inspired Renewable Energy,” 2. This story also illustrates how the intersection between Qur’anic and local knowledge has been theorized and put into practice by Muslim actors in local environmental efforts.

When Arahmaiani began to work in Tibet in 2010, she maintained an open approach to understanding local ways of being and relating to the ideas of nature as resources and creatures. In introducing the environmental measures to Kadheng Rinpoche and the rest of the monks at the Lab Monastery, Arahmaiani quickly learned that the eschatological framework so prominent in Muslim environmental consciousness would not resonate in Buddhist Tibet, where reincarnation is a widespread and prominent belief. Moreover, the more externally oriented ideas of piety and teachings in Islam that give equal weight to a vertical relationship to God and a horizontal relationship to other human beings could not be imposed unproblematically on Buddhist practices, which often distinguish between the monastic life and the lives of laypeople. For these reasons, she decided to study Buddhist teachings with the Dalai Lama in Sera Jey Monastery in South India. Arahmaiani soon learned the history of the Gelugpa order in Tibetan Buddhism and its historical connection to Indonesia and the Indo-Malay Archipelago through the figure of Lama Atisha Dipamkarashrijnana (982–1054 CE), a Buddhist religious teacher and master from India who spent twelve years in Sumatra and Java during the reign of the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of Sriwijaya and Medang Kamulan before coming to Tibet. Arahmaiani subsequently utilized Lama Atisha’s teaching about saving all living beings from suffering to reframe the urgency of the environmental crisis for the monks at the monastery.34Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021; Arahmaiani, interview by Jaya Suprana. Arahmaiani’s method and commitment to understanding the communities she works with in order to advance her environmental proposals also distinguish her activism from the work of interfaith NGO-based programs. The concern for “all living beings” in ecotheological consciousness, which challenges the anthropocentricity in environmentalism, also resonates with the Islamic teaching of the religion as “rahmatan lil alamin,” which is defined as “a blessing to the world” and all creation—a critical concept often adopted in the practice of Muslim environmentalism across the Islamic world.35Gade, Muslim Environmentalism, 101–2.

Arahmaiani’s concern for environmental issues in her activist-oriented and community-based collaborative works is an extension of her commitment as a Muslim to transcultural and interreligious dialogues that could (re)generate reparative readings toward Islam and Muslims and redress the violence imposed by modernization. Grounded in the action of ekofeminisme and reparative feminism, Arahmaiani believes that art “must do its part to encourage and empower communities and individual people to evaluate and understand their own situation and problems, particularly issues of cultural, social, political, and environment conflict.”36Arahmaiani, Artist Statement, Flag Project, Yogyakarta, September 1, 2010. Arahmaiani’s work reveals that the openness to learn about other faiths and ways of being has informed her engagement with different communities across the world and allowed her to move more flexibly in male-dominated spaces like the pesantren and monastery. The performative and ritualized reiterations of Proyek Bendera work on multiple levels: as consciousness-raising efforts in terms of environmental issues, healing rituals aimed at redressing the violence and injuries experienced by marginalized communities and those impacted by natural disasters, and spaces for open and egalitarian collaboration and exchange.

- 1Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author via WhatsApp, June 2021.

- 2Arahmaiani, Artist’s Statement, Flag Project, Yogyakarta, September 1, 2010. This document was shared with the author by the artist.

- 3See for example, Amanda Rath, “Contextualizing Contemporary Art: Propositions of Critical Artistic Practice in Seni Rupa Kontemporer in Indonesia” (PhD diss., Cornell University, 2011), 285–325; and Wulan Dirgantoro, “Arahmaiani: Challenging the Status Quo,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context, and Enquiry 42 (Autumn/Winter, 2016): 24–35.

- 4Edwin Jurriëns, “Gendering the Environmental Artivism: Ekofeminisme and Unjuk Rasa of Arahmaiani’s Art,” Southeast Asia of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 4, no. 2 (October 2020): 3–38.

- 5Ibid., 12.

- 6See ibid., 11–14.

- 7See Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–51.

- 8Joshua Chambers-Letson, “Reparative Feminisms, Repairing Feminism—Reparation, Postcolonial Violence, and Feminism,” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 16, no. 2 (July 2006): 176–77.

- 9Ibid., 173.

- 10Arahmaiani’s commitments and choice of materiality in her iterations of Proyek Bendera (Flag Project)also draw from her collaborative works in Bangkok, where she worked together with the local Muslim and silk-weaving community of Baan Krua. The project is titled Stitching the Wound and the exhibition was held at the Art Center at the Jim Thompson Art House in Bangkok. In this project, Arahmaiani also made use of and presented Jawi scripts in addition to working with local women and young girls to generate a creative dialogue manifested in their performance during the opening of the exhibition.

- 11Arahmaiani, Artist’s Statement, quoted in publication material for the iteration of the Flag Project at Kayu Lucie Fontaine Bali, April 27–May 31, 2019.

- 12Arahmaiani and Siobhan Campbell, “Balancing Feminine and Masculine Energy,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 3, no. 1 (March 2019): 206.

- 13See Barbara Watson Andaya, The Flaming Womb: Repositioning Women in Early Modern Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006).

- 14Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author, March 2018.

- 15My experience with and analysis of the many iterations of Arahmaiani’s Proyek Bendera is mediated by these videos and photo documentation in addition to Arahmaiani’s accounts, which I gathered through informal interviews and vernacular archives that the artist has shared with me since 2018.

- 16While Arahmaiani used Jawi writings in several previous iterations of Proyek Bendera, she only used it exclusively in 2010. For example, Arahmaiani’s I LOVE YOU installation and performance of Proyek Bendera at Esplanade in Singapore in 2009 displayed Jawi on one of the flags that Arahmaiani carried, but other flags contained words in different languages written in various scripts, including Latin and Chinese.

- 17Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author, May 2021. Arahmaiani shared her story of undergoing a healing ritual in Bali and told me that she remembered listening to tembang during the process.

- 18Arahmaiani, in conversation with the author, March 2018.

- 19Ibid.

- 20Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021. Kyai is an honorific title for an Islamic religious scholar or teacher.

- 21Anna M. Gade, Muslim Environmentalisms: Religious and Social Foundations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 66.

- 22Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021.

- 23Ibid. See also Kristina Großmann and Arahmaiani Feisal, “Islam-inspired Renewable Energy,” Inside Indonesia 133 (July–September 2018): 2–3. Despite Pesantren Amumarta’s commitment, Großmann and Arahmaiani observed in 2018 how the initiative stagnated as the biofuel failed to draw local government’s patronage (largely due to the lack of seriousness on the part of the local and national governments in battling environmental issues) and could hardly compete with the government’s fossil fuel subsidy.

- 24Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021.

- 25Arahmaiani, interview by Jaya Suprana, Jaya Suprana Show, streamed live on January 19, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hmGMVwQAwUw.

- 26Arahmaiani and Campbell, “Balancing Feminine and Masculine Energy,” 211–12. Known as the “water tower of Asia” the Tibetan Plateau is the source of water for major river lines that go through Asia, providing water to more than two million people across South, East, and Southeast Asia.

- 27Much of Arahmaiani’s environmental activism involving local communities does not seem to have a specific timeline for completion. Her work in Tibet is ongoing as she intends to return to Tibet when the COVID 19 pandemic is properly handled and countries reopen. She also maintains communication with the pesantrens and other communities she worked with in the past.

- 28Arahmaiani and Campbell, “Balancing Feminine and Masculine Energy,” 211.

- 29Historically the term nusantara refers to geographical areas that were once under the tributary rule of the Majapahit empire, the last Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Java. The areas included many parts of maritime Southeast Asia, including the modern-day Indonesian archipelago, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and Southern Philippines. The term itself remains relevant in today’s Indonesia, denoting the whole island of Indonesia, and is a part of the national and cultural identity.

- 30Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021. Arahmaiani disclosed to me her observation of the reliance of the community in Tibet on the (unhealthy) food supplies imported from mainland China. While she was cautious to not frame her work in Tibet as political, it is not a stretch to see the food import as a way to exert control over the population in Tibet. For this reason, the ability to achieve resources sovereignty through local production of (healthier) foods and water management could serve as a mode of subtle resistance.

- 31Gade, Muslim Environmentalisms, 110–13.

- 32Ibid., 3. Throughout the book, Gade argues the importance of acknowledging and emphasizing the prominent eschatological dimensions of Qur’anic messages in order to understand Muslim environmentalism and Islam. In the beginning of her book, she suggests, “Fundamental teachings on eschatology (‘last things’) seem as ethically relevant today as in the seventh century; so it is valid to generalize that Islamic commitments to the phenomenal world, so-called environmentalisms, would similarly address head-on the notion of responsible and human existence as that of being among other creatures in the face of the imminent potential for earth’s destruction.” Emphasis original.

- 33Großmann and Feisal, “Islam-inspired Renewable Energy,” 2.

- 34Arahmaiani, in discussion with the author via Zoom, May 2021; Arahmaiani, interview by Jaya Suprana. Arahmaiani’s method and commitment to understanding the communities she works with in order to advance her environmental proposals also distinguish her activism from the work of interfaith NGO-based programs.

- 35Gade, Muslim Environmentalism, 101–2.

- 36Arahmaiani, Artist Statement, Flag Project, Yogyakarta, September 1, 2010.