In an effort to consider the varied impacts of COVID-19—a virus with a global reach—post has interviewed curators and directors from vital museums and galleries around the world about how the pandemic has affected their ideas regarding programming, civic engagement, and the role of the institution. This is an interview with Katerina Chuchalina, Chief Curator at the V—A—C Foundation (Moscow and Venice).

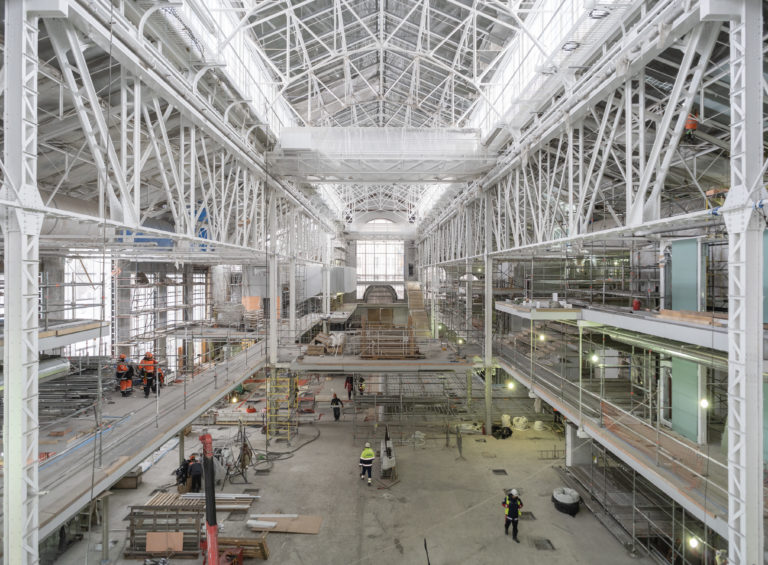

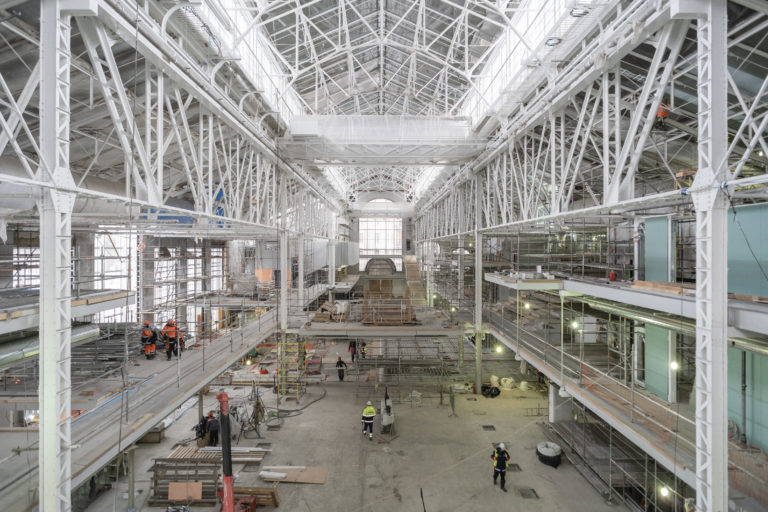

Inga Lāce: The V—A—C Foundation was planning to open in 2020 with a new building in the converted former site of GES-2, a power station right in the center of Moscow overlooking the Kremlin. How have you reshaped your current programs, themes, and the inner institutional workings in response to the global pandemic?

Katerina Chuchalina: Indeed, the global pandemic caught us by surprise as we were finalizing the opening program for GES-2, which was supposed to launch in September 2020. By March 2020, however, it was clear that this would not happen as the construction was inevitably delayed by the crisis. Like everyone else in the world, we began to recognize the destructive and generative potential of the virus, and we used the delay to analyze the state of our community and the ways in which the institution might support it. We used this continuous momentum to rethink the opening season. Our rapidly growing team has spent several years planning, designing, and creating the range of directions and disciplines encompassed within GES-2: dance, cinema, theater, music, a publishing program, community-based artistic practices and events, the urban studios and residency program, inclusivity and public programs, and of course, the exhibition part. This sort of planning is schizophrenic and exhausting. You need to be thinking several years ahead—imagining and designing in detail projects that will take place in a space that has not yet been built for people unaware of your existence—and then travel back to now, and amend all the projects over and over again to adapt them to the present.

This process has never been easy, but when the crisis broke, we had the time and space to rethink. As a result, we came up with the program preceding the opening of the first season of GES-2 and instigated by our desire to support local living artists and musicians, to introduce GES-2 as both a new, local venue and institution, and to show Renzo Piano’s architectural project in a never-to-be-experienced-again bare state—before it is used for programs and exhibitions. A series of newly commissioned site-specific works by Russian contemporary composers created and recorded in the aftermath of the global lockdown will play for a limited period of time as a sound accompaniment to the meeting between the city and its new institution. I hope that the conditions of the pandemic and the construction of the building will allow this pre-opening program to come true.

IL: Before undertaking a building plan for the V—A—C Foundation, your curatorial practice was more nomadic in that it involved working on-site within different museums. How would this reexamination of the existing museum collections and knowledge manifest in the work that is undertaken at GES-2?

KC: Indeed, in the ten years since its creation, the V—A—CFoundation has been engaged in mapping artistic processes focused on contemporaneity, the synchronization of present and past through dialogue, and the location of codes and tools to investigate important themes. For a long time, we did not have a building of our own and so operated outside the existing art infrastructure—doing projects, for example, at the Central Museum of the Armed Forces, Museum of Contemporary Russian History, Institute for African Studies, and GULAG History Museum, among others. We were able to occupy an unconventional position, one that allowed us to make a break in the continuous and undifferentiated history while also establishing new historical narratives through interventions involving contemporary artistic research. GES-2 will undoubtedly inherit this attention to thresholds and connections, and as such, aim to function as a storytelling institution—one that is fully immersed in the narratives surrounding Russia’s history and contemporaneity.

We have already designed a cycle of five seasons of programming, each including many exhibitions, performative, cinema, music, theatre and public programs entitled Holy Barbarians: Both Are Worse. Unfolding over the next three years, this incremental narrative is intended to engage critically with clichés and cultural tropes associated with Russia, mainly those projected from the outside, though also present within: great Russian literature, tyranny, the mother archetype, a propensity for melodrama, moral relativism, cosmos as an emblem of geo-cosmo-political superiority, etc. Among the clichés that will be explored—and the one that has inspired the title of the series—is the contradictory notion of “holy barbarism,” which embodies opposed phantasmal projections. This dilemma embodies, on the one hand, the age-old myth of Russian savagery and backwardness; and on the other, the (equally orientalist) idea of Russia’s irreducible uniqueness, “chosen-ness,” or even holiness. The format of a narrative in five parts, like a five-volume novel, is in itself a performative acting-out of the stereotype of so-called Russian literature-centrism. The choice of themes is guided by the fact that the clichés, in spite of (or, perhaps, thanks to) being deeply entrenched, raise questions that are relevant in a global context.

The first exhibition in the cycle, Santa Barbara. How Not to Be Colonized?, will feature a large-scale commission by Ragnar Kjartansson (Icelandic, born 1976), who is known for his interest in the emotional power of music and drama, in combination with contemporary Russian works exploring the carnivalesque in Russian culture from the 1990s onward. An attempt to travel back in time thirty years, this exhibition will reimagine the foundational myths of post-Soviet Russia and look at the images, cultural values, and ideas that have ingrained themselves in its collective consciousness since then. The starting point of this conversation is Santa Barbara, the first Western soap opera to be broadcast in Russia and the most enduring on post-Soviet television. Airing from 1992 to 2002, the show not only presented different cultural models and inspired an urge for self-determination, it also sparked resistance to Western homogenization, a movement in which Russian artists played a role. The Santa Barbara decade was a time for the reinvention of the self—at once emancipatory and carnivalesque—with myriad consequences, both intended and unintended.

Next, we will look at the conception of truth and realism, which translates in Russian as “istina,” or scientific truth or truth as a religious category, and “pravda,” which is an ethical concept related not only to theory, but also to actions and deeds. Mother: Why Motherland? continues the inquiry into cultural representations of Russia via questions related to motherhood, such as care, labor relations, family, gender dynamics, and kinship; Kosmos Is Ours will explore the universal cosmological impulse as well as the colonial drive behind it; while, finally, Barely Audible will focus on a shift in tonality rather than in the cultural landscape, and reflect on the possibility of an institutional space as one of genuine intimacy that is free of transactional uses.

IL: Museums are also important as they are fostering communities centered on learning and discussion. Are you working on that aspect prior to the opening of the building?

KC: We started to work on that the very moment we started to develop programming for GES-2, and in the process, one thing was fundamental: the program should be conceived together with educators and community builders, and not only by curators. Exhibitions, educational programs, discussions, and community programs are proposed and debated by the larger group of curators and educators in the framework of the season. Through this back-and-forth, we intend to break the hierarchical structure of exhibitions, concerts, and education. We want to make sure that the community-building and educational programs are conceived of and thus perceived as equal to and complementary components of the narrative—as opposed to accessory or merely illustrative of the main program of exhibitions and live events.

IL: You mention that one part of the program will focus on the dynamic surrounding the Western cultural colonization of Russia in the post-Soviet period of the 1990s. Do you also envision examining the Soviet Union as a colonial project, and the historical and still present cultural, infrastructural, and political interconnections therein—that is, to think about how Russia relates to post-colonial and decolonial debates?

KC: Absolutely. The fourth seasonal program Kosmos Is Ours will look at who we are if we continue to expand our presence in time and space, and identify the local and pluriversal cosmologies currently in place and now forced to unite in a seemingly possible universality by various geopolitical regimes. This conversation cannot happen without meticulous investigation of the Soviet colonial impulses and structures, which is of course not possible without inviting participation of artists and curators from the states within the former USSR.

IL: Earlier this year, large-scale demonstrations broke out across Russia against the arrest of Alexey Navalny and the ongoing corruption of the current government, generating a lot of reactions in the local and international media, as well as from Western governments and Russia itself. Are the roots and objectives of these protests adequately represented locally and in the international media, in your opinion, given the complexity of the situation? How do you see the role of cultural institutions in the process?

KC: Both the mainstream Western media channels and the official local ones have oversimplified the situation. Indeed, both sides broadcast news in a predictable way, reaffirming the information warfare in a rather old-fashioned manner. And to be honest, local media channels are not that scarce now and don’t sound unanimously; mostly online, some of them do offer nuanced consideration of the moment, addressing different possible futures and vectors, but this kind of analysis is outside that of the international mainstream and the official local mass media outlets.

As we all know, culture is a continuation of politics (in the broadest sense of the word) by other means, and I think an institution always aspires to contribute to creating a more nuanced portrait, to offer a mirror reflecting society’s fears, biases, and internalized clichés as well as its strength and common futures. But of course, an institution is not only aiming at representation but also at creating a platform for active engagement, polemics and debates.

IL: Some of the artists you have commissioned through the V—A—C Foundation, such as Kirill Savchenkov (born 1987) and Arseniy Zhilyaev (born 1984), have been referencing visionary futures or science fiction from the past. What do you think we could draw from this sort of work in terms of thinking about the future of our museums, art ecosystem, and the planet?

KC: Both artists that you mention indeed engage with different modalities—not necessarily referring to science fiction from the past, but rather different systems. Savchenkov deals with knowledge systems and practical skills—from various cosmological systems to paramilitary, meditative and new media practices—that human intelligence can navigate and use to survive in the world bombarded by crises, global instability and in the potential conditions of the posthuman future. Zhilyaev explores existing intersections, or creates new ones between art, philosophy, and science; often these encounters take place in an imaginary institutional space, a museum, but at a moment in time that is unreachably remote from the present. It is always a reinvention of an art institution, rearranging the system components of knowledge and practice to get to some common future beyond geographies and prescribed functions. I know how difficult it may be for an institution to follow and trust artistic intuition while building a new museum, but I believe that doing so is the only way for all of us to get there.