Starting with an examination of the impact of the global banana market on Latin America, this text analyzes the work of María José Argenzio and Óscar Figueroa Chaves, two artists who expose how multinational corporations operating in Latin America have benefited from monoculture and extraction practices in the region.

The global export of bananas, an international food staple, has significantly shaped the history of Latin America since the late nineteenth century. Today, many contemporary artists from the region reflect on the current environmental challenges that their native countries face by exploring the exploitation endured by the continent for centuries. In many cases, their artworks examine how the massive growth of the banana industry in Latin America has contributed to increased social disparities in the region, altered local culture and traditional ways of life, and irremediably affected the landscape and ecosystems. This text analyzes the work of María José Argenzio (born Guayaquil, Ecuador, 1977) and Óscar Figueroa Chaves (born San José, Costa Rica, 1986), two artists who expose how multinational corporations operating in Latin America have benefited from monoculture and extraction practices in the region, not only for massive profits but also to test neoliberal operations prior to their implementation in other areas—thereby using the region as a test site for plutocratic policies.

The establishment of a global banana market by the United Fruit Company (UFC) in the early 1900s ushered in an era of bananas as a cash crop, a designation that brought with it the brutal stifling of any protests against the accompanying harsh labor conditions, and even the toppling of governments that dared oppose them through the endorsement of local coups. The self-interested agitations of political and economic instability incited by the UFC eventually led to the coining of the term “Banana Republic” as a reference to poor, corrupted, and underdeveloped nations, glibly recognizing the massive influence that foreign interests could wield in this region. Multinational banana corporations continue to operate in Latin America today—more than one hundred years later—supplying the world mainly with a single variety of the fruit: the Cavendish.1“The Problem with Bananas: Environmental, Social & Corporate Issues,” BananaLink, https://www.bananalink.org.uk/the-problem-with-bananas/#:~:text=Monoculture%20%26%20High%20Input%20Production&text=At%20least%2097%25%20of%20internationally,are%20applied%20to%20the%20crops. This lack of genetic variety within what is a massive crop makes the plants highly susceptible to fungi and diseases, necessitating the use of large quantities of insecticides.2Rebecca Cohen, “Global Issues for Breakfast: The Banana Industry and Its Problems FAQ (Cohen Mix),” Science Creative Quarterly, June 12, 2009, https://www.scq.ubc.ca/global-issues-for-breakfast-the-banana-industry-and-its-problems-faq-cohen-mix/. Moreover, bananas are in general an ecologically demanding species—because their trees shed no natural leaf litter to feed the soil, which quickly becomes depleted of nutrients, more and more land is required to meet global demand.3Ibid. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the overuse of fungicides and insecticides in the banana industry can lead to health issues in humans, particularly among plantation workers who have close and extended contact with them.4“World Banana Forum: Good Practices Collection: Pesticide Management in the Banana Industry”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (hereafter abbreviated as FAO), http://www.fao.org/3/i6840e/i6840e.pdf. These toxic substances not only drain the soil of nutrients to the point that nothing will grow in it, but also, in many cases, seep into aquatic systems, affecting the habitat of species near and far.5Daniel Ahrendt et al., “Bananas: Environmental Impacts of Banana Growing,” (Writing 101:01 group project on the theme of “Sustainability,” Pacific Lutheran University, May 2007).

The baffling willingness to sacrifice human lives in favor of the apparently always-rising value of natural resources is addressed in the work of artist María José Argenzio. A fundamental line of research within her oeuvre is the relationship between materiality and allusions to dynamics of power, inequalities, and injustices within the history of her native Ecuador. In artworks such as 3° 16′ 0″ S, 79° 58′ 0″ W (2010) and Chiquita (2013), these relationships are evidenced through the application of gold leaf—an ornamental technique used especially during colonial times—and the iconography of bananas. These two natural resources are characterized by their high production and extraction in Ecuador. From the colonial period until today, both gold and bananas have served as means for the consolidation of power hegemonies, almost always dominated by foreign forces that have taken advantage of the low cost of local labor. While the exploitation of bananas and gold became big business for these foreign intermediaries, for the locals who work on the plantations or in the mines, the work is arduous and brings little money. In addition, these workers are constantly exposed to pesticides and other chemicals that put their health at risk.

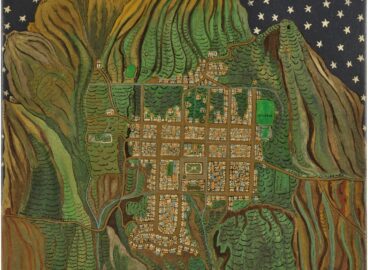

In 3° 16′ 0″ S, 79° 58′ 0″ W (2010), Argenzio utilized a traditional gold-plating technique to coat a banana plant in the middle of a plantation located in the Ecuadorian province of El Oro (The Gold). Ironically, the name of this region, which has the highest banana production in Ecuador, symbolically unites in a single space the history of the extraction of two internationally coveted natural resources. 3° 16′ 0″ S, 79° 58′ 0″ W is usually presented through two projected photographs: one an aerial view of the vast green landscape of the banana plantation where the gold-plated banana tree shines bright amid the verdure, and the other a shot of the gilded plant taken from a low-angle point of view. In this intervention, Argenzio synthesizes the issues present in the massive commercialization of bananas and gold, and in a powerful gesture, condenses the processes of extraction undertaken in this territory: During colonial times, gold was a marker of status and wealth, and its extraction and trade can be traced across the Spanish Empire, while today, Ecuador is the largest banana exporter in the world.6“Banana Market Review: February 2020 Snapshot,” FAO, http://www.fao.org/3/ca9212en/ca9212en.pdf. This ongoing role in the worldwide economy has local repercussions, such as the high volume of pesticides considered necessary to maximize the yields, which affects both humans and the landscape, and the uneven distribution of the profits in the market chain, which creates significant social inequalities.7Aziz Elbehri et al., “Ecuador’s Banana Sector under Climate Change: An Economic and Biophysical Assessment to Promote a Sustainable and Climate-Compatible Strategy,” FAO, 2016, p. 16, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5697e.pdf. With a title that corresponds to the precise location of the intervention, 3° 16′ 0″ S, 79° 58′ 0″ W makes visual and brings to the fore these pressing issues through deployment of the precious mineral in an unexpected way. By gold-plating the banana tree, the artist interchanges the value of the two products, in effect nullifying their original intended uses. The banana plant will die before its fruit can enter the international trade system, and the valuable gold-plating—originally intended for use in religious contexts—will be lost in the middle of a plantation, its value reduced to a sort of armor, protecting the plant from pesticides, but ultimately suffocating it.

In a similar way, Argenzio’s work Chiquita (2013), a sculpture composed of three bananas made of resin, bathed in gold, and arranged on a black velvet cushion in the manner of a jewel, explicitly exposes the tensions between the chain of production and the consumption of natural resources. The piece addresses the presence in Ecuador of Chiquita Banana, formerly UFC, the American company that has dominated the fruit market for decades. The colonial past and modern development of a country such as Ecuador become explicit in Argenzio’s works that, through the use of a baroque aesthetic alluding to the ongoing colonial power structures, question the symbolic and material stories of national identity.

For more than a decade, Óscar Figueroa Chaves has explored the legacy of the plantation economy in his native Costa Rica, where the UFC operated from 1899 until 1984, when it represented 20 percent of the nation’s total export trade. Interested in the banana trade history shared by Central America and the Colombian Caribbean, the artist traveled by foot from Guatemala to Colombia, tracing the remains of the railroad tracks that were crucial to the consolidation of the international banana market. During this trip, which inspired the work Durmientes (2012–13), Figueroa Chaves took notes and created low reliefs using rice tracing paper, pencil, and ink of the wooden tracks from around which he also collected dead insects and nails. As a contemporary take on nineteenth-century travel sketchbooks, the work speaks to the banana trade’s monopolization of the regional economy. The title of the work, Durmientes (Sleepers), alludes to the name given to the now-abandoned railroad tracks—once the epitome of progress and development but now the legacy of an abusive system that cost the lives of many railroad and plantation workers from disease, lack of sanitary measures, and abusive working conditions.

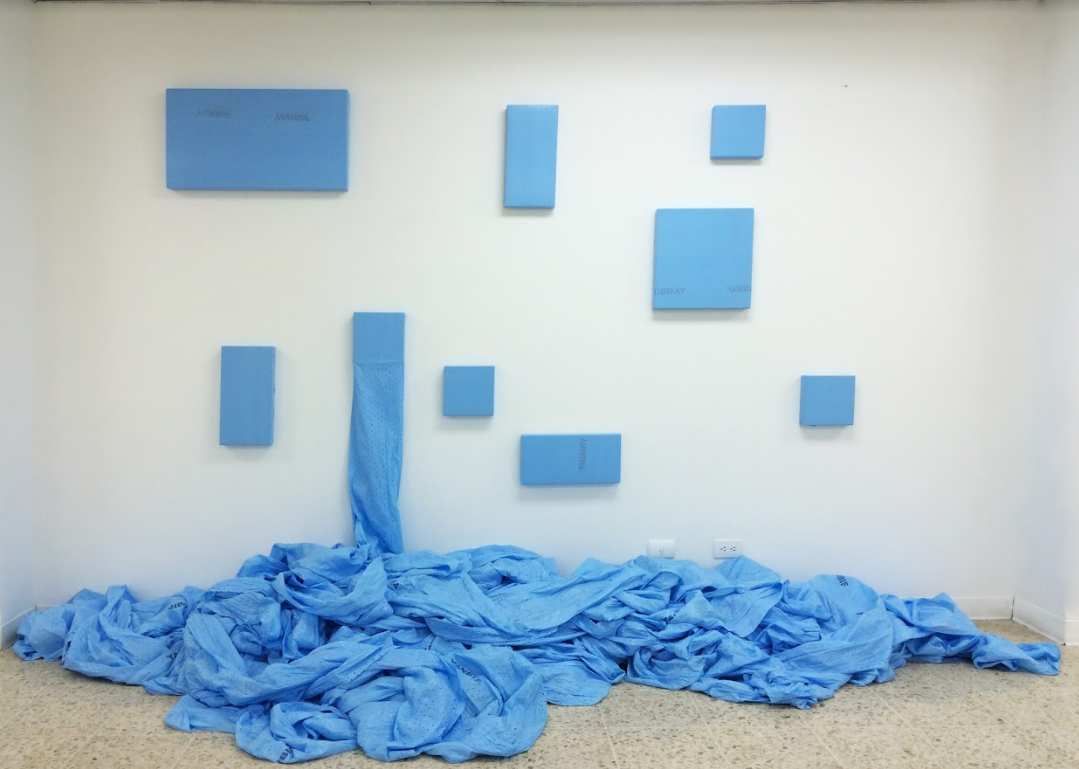

In Costa Rica, the building of a railroad system connecting the important cities of Turrialba and Limón was key to the development of the profitable banana industry. And unsurprisingly, while it was one of the most expensive railroad construction projects at the time, its cost in terms of human life was devastating. Deméritos (Demerits; 2012) is a video-recorded performance documenting the tracing of what used to be the railroad tracks of Turrialba with almost 10,744 feet (3,275 meters) of bright blue plastic bags sprayed with pesticide and arranged in a long line. Executed on October 12, 2012 (problematically celebrated in many countries as Columbus Day, which highlights current forms of colonialism), the visually striking blue bags were originally used to protect bunches of bananas prior to harvest on the plantations. Thus, the bright blue track signaled by Figueroa Chaves’s action calls attention to the devastating effects of the banana monoculture on the economy, the landscape, and the culture of the region. Through the use of the blue bags, the artwork also suggests that perhaps it was the plantation workers, and not the banana bunches, who needed to be protected from the “pests” brought about by the multinationals operating in Costa Rica. Furthermore, the setting of this action in Turrialba also alludes to the government’s order, instigated by the UFC in the early twentieth century, to prohibit the Afro-Jamaican population and Chinese migrants working in the banana fields from traveling westward, beyond Turrialba, where new, “whiter” plantation industries were being constructed.8See María José Chavarría, On the Other Side of the Railroads: Oscar Figueroa Chaves, exh. cat. (San José, Costa Rica: Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo, 2015) and artist Óscar Figueroa Chaves’s blog, http://oscarfigueroachaves.blogspot.com/2016/09/intervencion-antiguas-oficinas-de-la.html.

The harmful effect of pesticides is the thread connecting several works by Figueroa Chaves. In 2012, the artist used the blue plastic bags to create “canvas paintings” that overflowed, spilled, and spread into the galleries where they were shown. The overwhelming, almost invasive effect of the sea of blue plastic covering the gallery floors evoked the destructive effects of the UFC in Central America. Four years later, for the tenth edition of the Bienal Centroamericana, curated by Tamara Díaz Bringas, Figueroa Chaves used the iconic bright blue plastic bags to wrap the UFC headquarters in the Costa Rican city of Puerto Limón. Visually reminiscent of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s site-specific environmental installations, this work symbolically limited the company’s ability to operate beyond its building. By confining the UFC within its own pesticide-sprayed plastics, the artist aspired to call out, in a monumental and symbolic way, international neoliberal businesses that use the Global South as a laboratory for the development of abusive, extractionist economic practices, and therefore to metaphorically protect the local community from UFC.

The works of these two artists unmask the ways in which the banana monoculture has impacted the landscape, life, and culture of Latin America and the Caribbean. The abusive agricultural exploitation of these countries has not only contributed to the consolidation of Orientalist stereotypes but has also had important repercussions in terms of the environment-dependent economy of many of these countries, climate change, and social inequalities. Although there have been efforts to reduce the abusive practices of the banana companies toward local laborers and their employers, the impact of the atrocities that these entities committed against native communities remains unresolved.9For example, the case against Chiquita Banana for the crimes they abetted to commit in Colombia between 1997 and 2004. For more information, see Dana Walters, “Human Rights Clinic team submits amicus brief in Chiquita Brands lawsuit,” Harvard Law Today, August 25, 2020, https://today.law.harvard.edu/human-rights-clinic-team-submits-amicus-brief-in-chiquita-brands-lawsuit/ Moreover, the wide use of pesticides is still a major problem, and the abusive utilization of toxic chemicals has had devastating effects on the environment. Argenzio and Figueroa Chaves denounce how the ambition of corporations has resulted in displaced communities and barren lands—among other harmful consequences—and call for active resistance by exposing pressing issues related to the extraction, exploitation, and trade of this apparently innocuous fruit.

- 1“The Problem with Bananas: Environmental, Social & Corporate Issues,” BananaLink, https://www.bananalink.org.uk/the-problem-with-bananas/#:~:text=Monoculture%20%26%20High%20Input%20Production&text=At%20least%2097%25%20of%20internationally,are%20applied%20to%20the%20crops.

- 2Rebecca Cohen, “Global Issues for Breakfast: The Banana Industry and Its Problems FAQ (Cohen Mix),” Science Creative Quarterly, June 12, 2009, https://www.scq.ubc.ca/global-issues-for-breakfast-the-banana-industry-and-its-problems-faq-cohen-mix/.

- 3Ibid.

- 4“World Banana Forum: Good Practices Collection: Pesticide Management in the Banana Industry”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (hereafter abbreviated as FAO), http://www.fao.org/3/i6840e/i6840e.pdf.

- 5Daniel Ahrendt et al., “Bananas: Environmental Impacts of Banana Growing,” (Writing 101:01 group project on the theme of “Sustainability,” Pacific Lutheran University, May 2007).

- 6“Banana Market Review: February 2020 Snapshot,” FAO, http://www.fao.org/3/ca9212en/ca9212en.pdf.

- 7Aziz Elbehri et al., “Ecuador’s Banana Sector under Climate Change: An Economic and Biophysical Assessment to Promote a Sustainable and Climate-Compatible Strategy,” FAO, 2016, p. 16, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5697e.pdf.

- 8See María José Chavarría, On the Other Side of the Railroads: Oscar Figueroa Chaves, exh. cat. (San José, Costa Rica: Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo, 2015) and artist Óscar Figueroa Chaves’s blog, http://oscarfigueroachaves.blogspot.com/2016/09/intervencion-antiguas-oficinas-de-la.html.

- 9For example, the case against Chiquita Banana for the crimes they abetted to commit in Colombia between 1997 and 2004. For more information, see Dana Walters, “Human Rights Clinic team submits amicus brief in Chiquita Brands lawsuit,” Harvard Law Today, August 25, 2020, https://today.law.harvard.edu/human-rights-clinic-team-submits-amicus-brief-in-chiquita-brands-lawsuit/