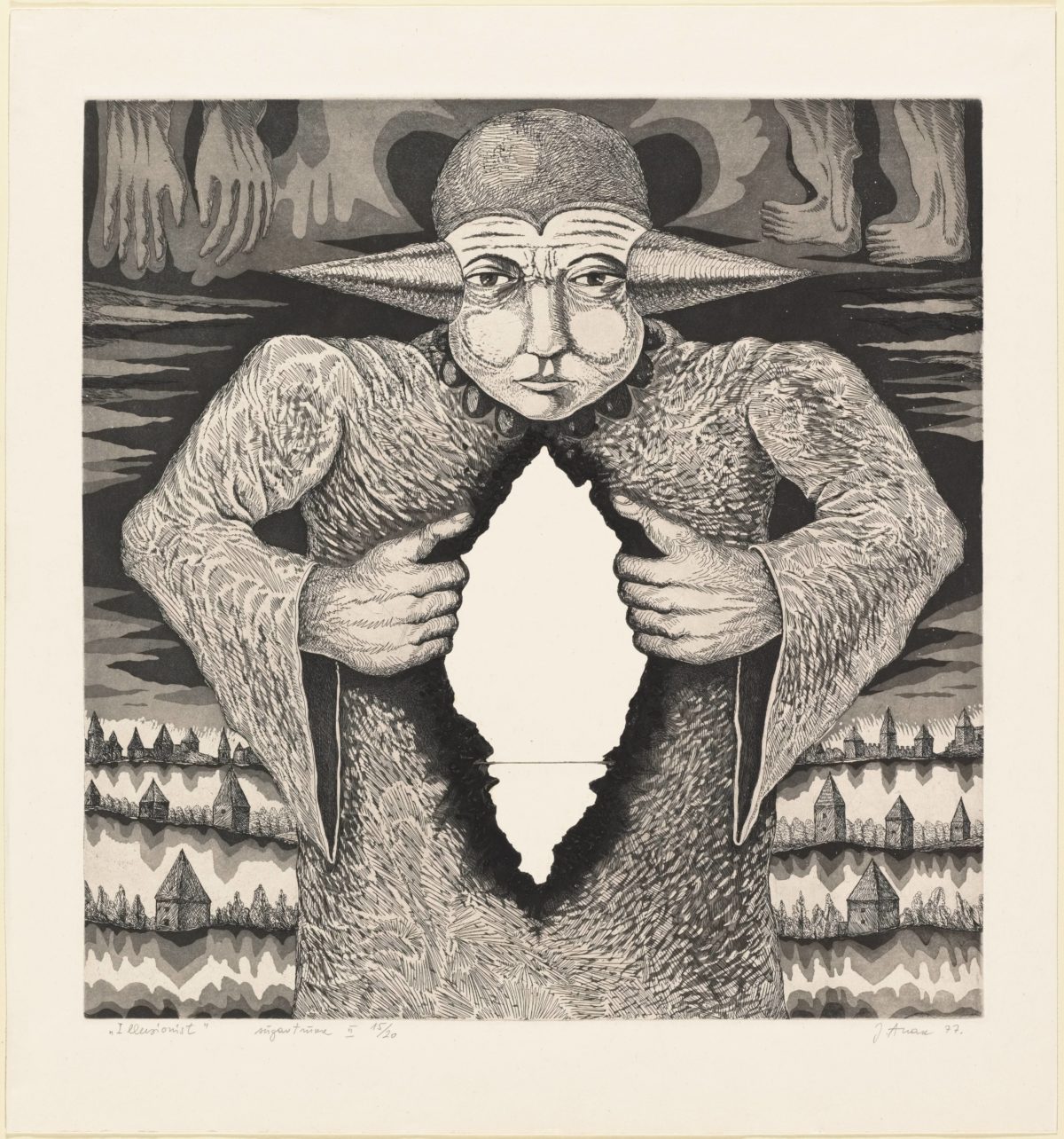

This essay looks at The Illusionist (1977), a print by Estonian artist Jüri Arrak in MoMA’s Drawings and Prints collection. It explores the larger context of the artist’s practice, which has spanned the avant-garde and turned toward mythological imaginaries, as well as represented the transformation of the strategies of resistance taken up by Estonian artists of his time.

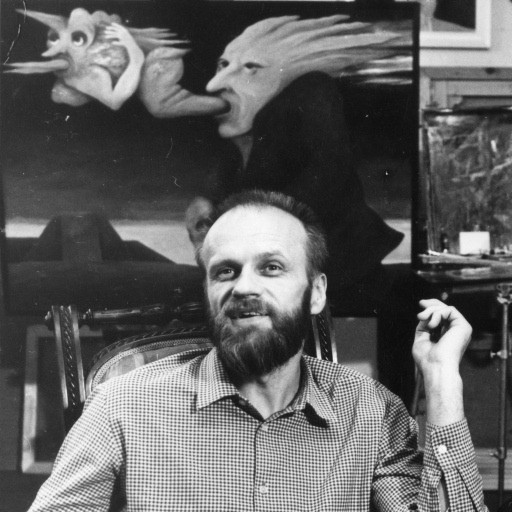

Jüri Arrak (born 1936) is undeniably one of the most well-known artists in Estonia. The reason for his immense popularity is probably his elaborate pictorial world. Arrak’s imagery is immediately recognizable and vaguely familiar—as if it belongs in a forgotten reality embedded deep in the collective unconscious.

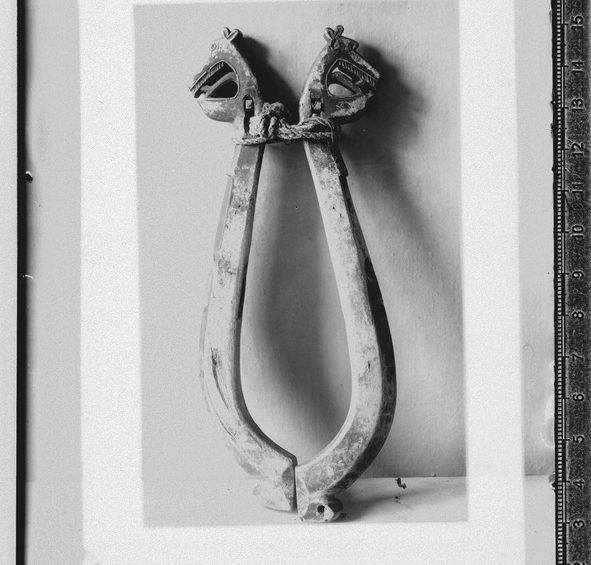

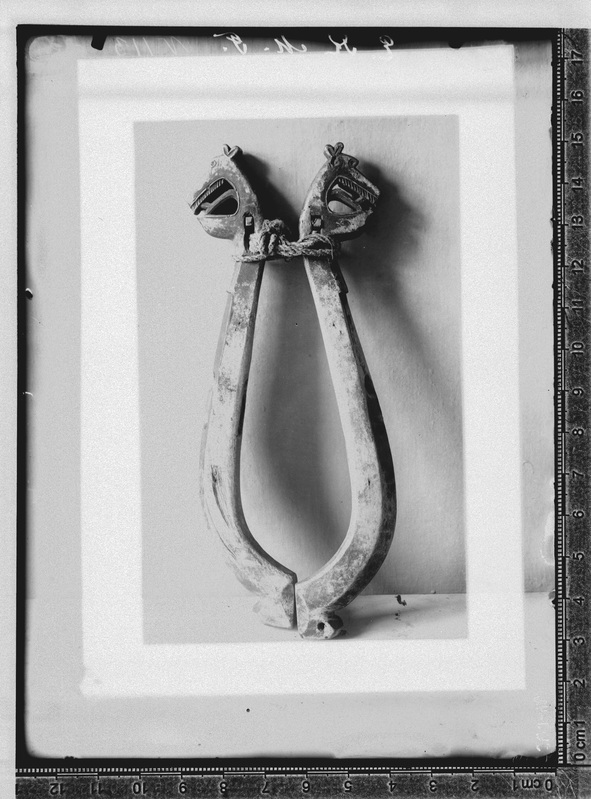

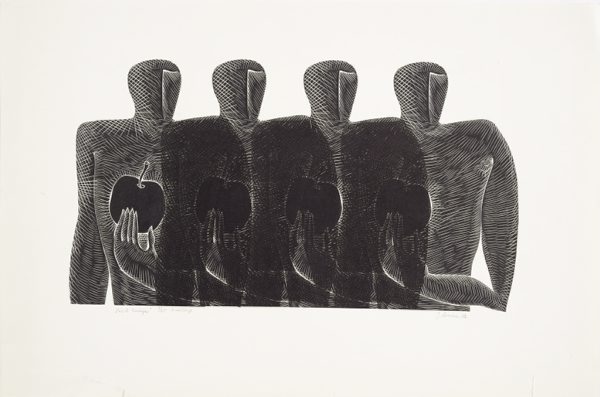

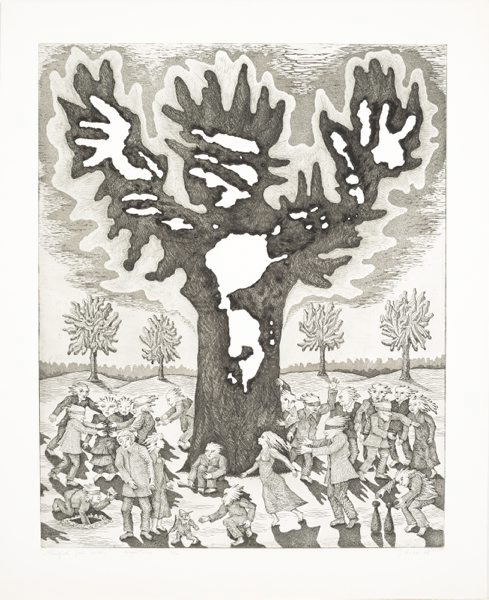

Arrak has cultivated his visual language for more than half a century, through painting and metalwork, prints, and drawings. Inspired by the pagan culture of archaic Estonia—as much as by his own imagination—his imagery represents a flexible semiotic system. His images, somewhat reminiscent of Estonian archaeological and ethnographic artifacts, nonetheless depict all kinds of events—folkloric and legendary, historical and current. Over time, Arrak’s pantheistic world view came to be more focused on specific religious subject matter, in particular, Christian ethics, which he has embraced as his own artistic mythology.

However, Arrak hasn’t always worked with imagery from mythological, religious, folkloric, and figurative art historical traditions. In the 1960s, he belonged to ANK ’64, which is considered the first artist collective in Soviet Estonia. Active from 1964 to 1969 in Tallinn, this group served as a catalyst in the re-modernization of the local art scene. When the artistic developments of the 1920s and 1930s were squelched by the Soviet occupation in the 1940s through 1960s, digressions from the Socialist Realism canon were often met with sanctions. Nonetheless, during the Khrushchev thaw,1The period in which Nikita Khrushchev served as first secretary of the Communist Party (1953–1964) is generally associated with de-Stalinization of the Soviet Union, and a more liberal (cultural) policy. young artists of ANK ’64 and their circle were able to break free of some of the dominating Realist paradigm.

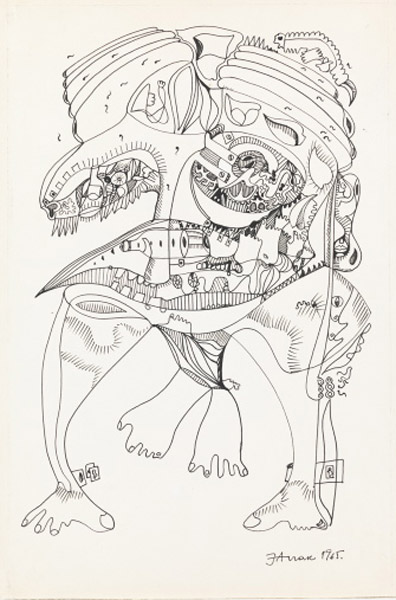

As ANK ’64 leader Tõnis Vint (1942–2019) declared in the 1960s, contemporary artists had to be well versed in both art history and contemporary art (including art made behind the Iron Curtain),2“Contemporary art, having extensively revealed all of the possibilities inherent in various technical qualities and having provided artists with completely new universal image structures within Pop art, creates a situation in which art emerges (along with many other phenomena), which is spiritually connected to the art of the Early Renaissance period, in terms of both its social significance and the depth of cognition.” Tõnis Vint, “Olukord 1968” [“Situation 1968”], Visarid 1 (1968): Tõlkekogumik. Prantsuse kaasaegsest kunstist [Visarid 1 (1968): Collection of Translated Articles on Contemporary French Art], from samizdat almanac of the artist group Visarid, circulated as a machine type manuscript now in the collection of the Art Museum of Estonia, pp. 1–5. Translation by Kadi Sutter. as well as in the latest developments in science and technology.3“Advances in science do not just significantly alter our relationship to objects of art but also drastically change the traditional understanding of beauty. Technology, chemistry labs, schematics, charts, photos of electron microscopes, etc. have become a part of our everyday lives. All of these new forms and combinations of single elements, which are created for purely practical reasons, the new harmonies of colours and forms which we can see in photos of objects under examination, gradually, but consistently, change our understanding of beauty. Soon, we will start seeing these new forms and colour harmonies in the works of contemporary artists, as a new aesthetic ideal befitting our time emerges and a new concept of beauty evolves.” “‘Nooruse’ rohelises auditooriumis [“In the Green Auditorium”]: Tõnis Vint,” Noorus, no. 8 (1968): 6–7. Translation by Kadi Sutter. This notion can be traced in Arrak’s works of the second half of the 1960s, in his experiments with ready-mades, his interest in abstract and surrealist visual expression as well as historical painting—from Renaissance religious painting to nineteenth-century Russian realist works—and his allusions to the Machine Age and the encroaching Technological Age.

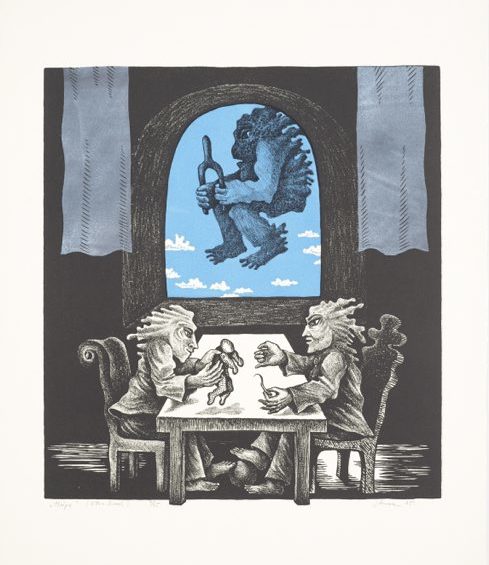

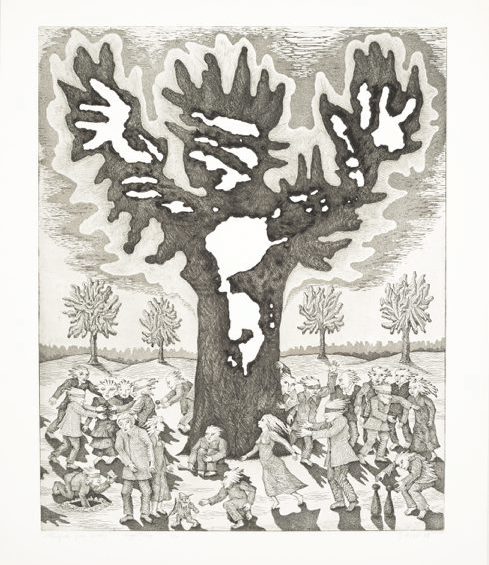

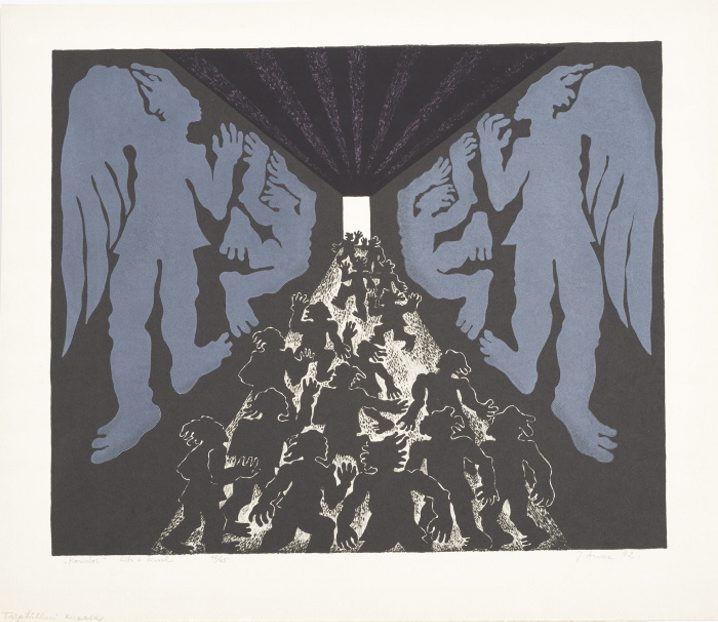

The events of the Prague Spring and their upshot in 1968 disrupted the artistic freedom of the Thaw, dashing hopes that the Soviet regime might grow more liberal and open. As a result, many artists chose to abandon modernist experiments and return to more traditional forms of figuration and symbolic expression—that is, to more “acceptable” subject matter. Exploring Estonian heritage became a form of hidden resistance and a means of preserving national culture in the face of enforced Russification. It was in this context that Arrak began to develop a world of his own, one inhabited by archaic figures. Among his illustrations of Estonian and Finnish epic tales and folklore, Estonian proverbs and games, are more bizarre, ambiguous depictions that not only evoke old myths and legends, but also function as allegories for the contemporary world.

The year 1968 marked the Prague Spring—and the founding of the Tallinn Print Triennial, an exhibition of contemporary printmaking with a focus on the Baltic region.4The first Tallinn Print Triennial, titled Present Day and Graphic Form, took place in 1968. Three Baltic countries—Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—took part. Initially it was meant to be a biennial, but the exhibitions evolved into a triennial. Indeed, despite the political climate, the 1970s came to be a Golden Age of Estonian graphic culture, both conceptually and in terms of printmaking technology. Printmaking was considered lower than painting and sculpture in the Soviet hierarchy of arts, and thus was not censored as strictly. Because it allowed for more artistic freedom, many Estonian artists acquired printmaking skills, and via editioning, went on to create multiples of their images, which they sent to international exhibitions—notably, the International Print Biennial in Krakow and the Biennial of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana. In this way, local artists overcame the Soviet isolation and were able to circulate their ideas abroad. Arrak took part (as a rule, unofficially) in many such international print shows throughout the 1970s.

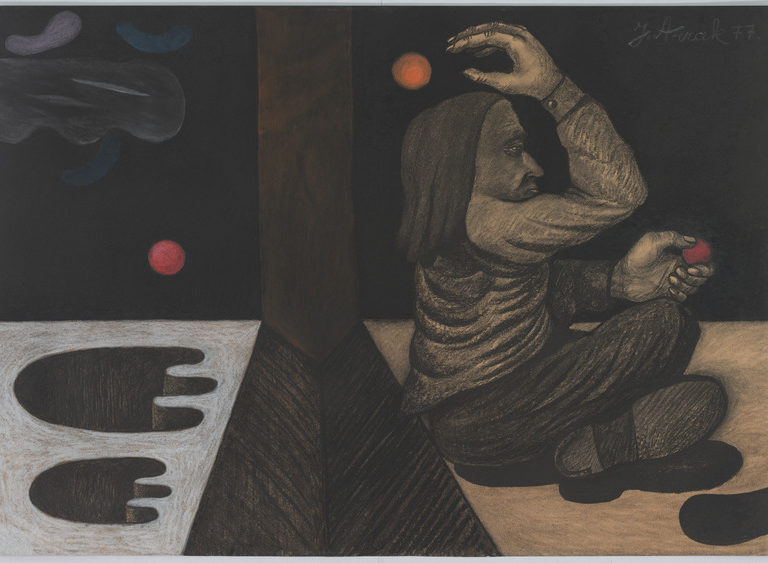

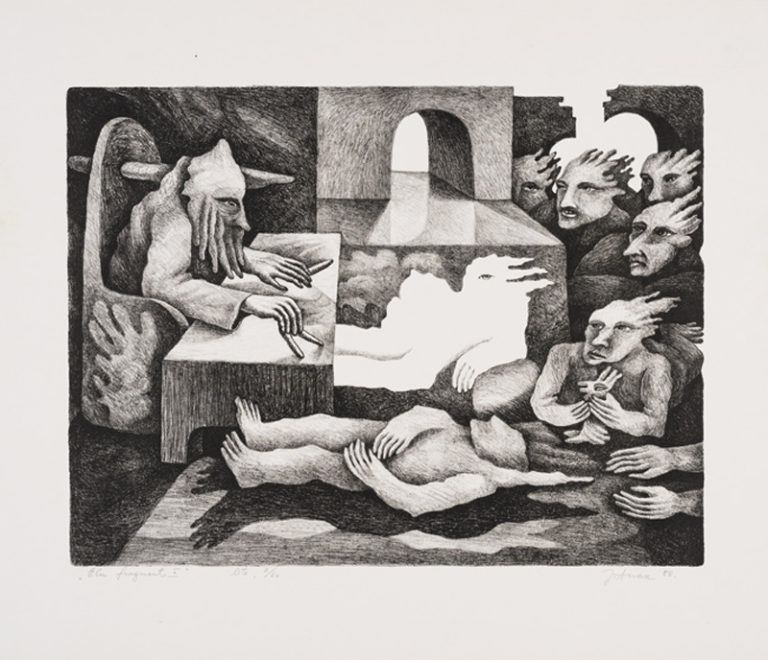

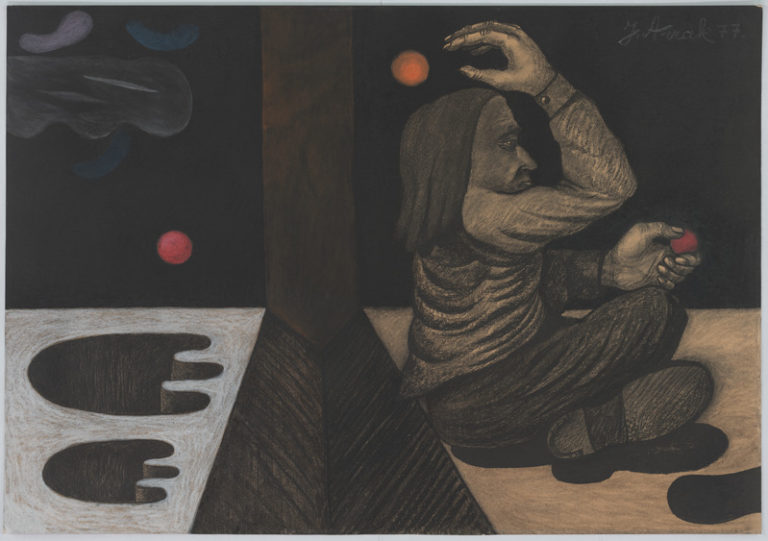

The Illusionist was made in the second half of the 1970s and reflects the maturing of Arrak’s pictorial system. It depicts a man who, standing in front of an archaic fortification built of towers, wears a bizarre helmet that perhaps alludes to his special status, that is, to his connection to the world of the spirits and magic. Above him, there are sets of feet and hands that may in fact extend from his headgear—it is hard to say. As the title suggests, the main subject is a magician in the middle of his performance. But instead of showing us something, he invites us to look at nothing: there is emptiness in his open chest, which makes the atmosphere of the work uncanny and surreal. Although surrealism was formally adapted in Soviet Estonia, it was seldom followed consistently as a conceptual method: Arrak’s surreal forms aim mainly at generating a sense of the fantastic. The artist was more interested in Carl Jung’s collective unconscious than in Sigmund Freud’s subconscious: he employed automatist techniques emphasizing individual visions in his earlier work, only to later turn to more consciously constructed universal or symbolic figures.

The Illusionist might not have a concrete protagonist parallel in Estonian folklore, but it certainly evokes mythological subjects. It also has roots in the Zen Buddhist conception of emptiness, popular on both sides of the Iron Curtain at the time. As in other Soviet countries, in Estonia, Zen Buddhism, Taoism, alchemy, and other mystical teachings represented alternative knowledge, one in opposition to the Communist Materialist, or nonreligious, world view. Whether artists of this period were striving for transcendence—whether they were seeking a better reality in terms of worldly freedom or envisioning a spiritual, higher reality—is often unclear. The Illusionist is a polysemic figure, at once a dissident and a protagonist of a Buddhist aporia, an alchemical trickster and a pagan shaman. In any case, it is certain that he reveals a portal to another world. Even if we don’t know what kind of world, we feel the presence of an alternate reality—a main characteristic of an artistic mythology.

The Illusionist is also interesting as an example of how a rather traditional-looking artwork conveys political resistance and the alternative ideas of its time. With its archaic visual language, the work touches upon several topics, none of which were approved by the Soviet regime in Estonia. And in doing so, it stands for the preservation of local culture and for individual artistic expression. This artwork embodies the archetypal notion of trespassing, the eternal attempt to reach the unknown—a universal journey named and depicted in different ways at different times and places.

*This and all the further images in this text are from the database Muis.ee.

- 1The period in which Nikita Khrushchev served as first secretary of the Communist Party (1953–1964) is generally associated with de-Stalinization of the Soviet Union, and a more liberal (cultural) policy.

- 2“Contemporary art, having extensively revealed all of the possibilities inherent in various technical qualities and having provided artists with completely new universal image structures within Pop art, creates a situation in which art emerges (along with many other phenomena), which is spiritually connected to the art of the Early Renaissance period, in terms of both its social significance and the depth of cognition.” Tõnis Vint, “Olukord 1968” [“Situation 1968”], Visarid 1 (1968): Tõlkekogumik. Prantsuse kaasaegsest kunstist [Visarid 1 (1968): Collection of Translated Articles on Contemporary French Art], from samizdat almanac of the artist group Visarid, circulated as a machine type manuscript now in the collection of the Art Museum of Estonia, pp. 1–5. Translation by Kadi Sutter.

- 3“Advances in science do not just significantly alter our relationship to objects of art but also drastically change the traditional understanding of beauty. Technology, chemistry labs, schematics, charts, photos of electron microscopes, etc. have become a part of our everyday lives. All of these new forms and combinations of single elements, which are created for purely practical reasons, the new harmonies of colours and forms which we can see in photos of objects under examination, gradually, but consistently, change our understanding of beauty. Soon, we will start seeing these new forms and colour harmonies in the works of contemporary artists, as a new aesthetic ideal befitting our time emerges and a new concept of beauty evolves.” “‘Nooruse’ rohelises auditooriumis [“In the Green Auditorium”]: Tõnis Vint,” Noorus, no. 8 (1968): 6–7. Translation by Kadi Sutter.

- 4The first Tallinn Print Triennial, titled Present Day and Graphic Form, took place in 1968. Three Baltic countries—Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—took part. Initially it was meant to be a biennial, but the exhibitions evolved into a triennial.