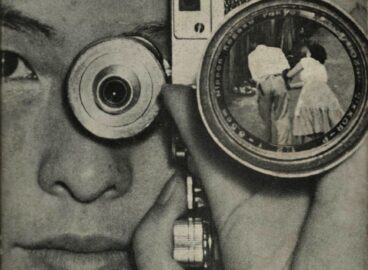

Hamaya Hiroshi’s Composition of December 1953 stands out from his more human-centric photographic practice. The American military vehicle crossing a snowy landscape becomes a marker of US occupation and the climate of post-war Japan.

This is not one of my pictures which I like best, because the picture is seized with forms to [sic] much. I want to take souls of whatever objects which I catch with my camera. This is my attitude always.

—Hamaya Hiroshi1“Remarks” from typewritten photograph record for Composition. 199.59, described as “Impression of a truck in the snow,” taken by Hiroshi Hamaya on December 1953, City of Otaru, Hokkaido, Japan. Department of Photography, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Hamaya Hiroshi’s favorite subject was the human being. In his renowned photo books Snow Land2Hamaya Hiroshi, Snow Land (Yukiguni; Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha, 1956). and Japan’s Back Coast,3Hamaya Hiroshi, Japan’s Back Coast (Ura Nihon; Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1957). he captured the hardscrabble lives of villagers in their stark natural environment in remote Japan. Unlike his more famous counterpart Tomatsu Shomei, who created iconic images of the “Americanization” of Japanese cities, Hamaya focused on the timeless countenances and rituals of Japanese agrarian life in the decade after World War II, aware that they were doomed to obsolescence amid the onslaught of Western convenience.

In the preface to Snow Land, anthropologist Shibusawa Keizo, who was Hamaya’s mentor, observes, “Hamaya’s photographs of Japanese folkways are simultaneously shashin写真 [portraits of truth] and shashin写心 [portraits of spirits],” playing on the homophones “truth” and “spirit.”4Shibusawa Keizo, preface to Snow Land, by Hiroshi, n.p. Decades later, in 1991, the curator of a Hamaya retrospective at the Hiratsuka City Art Museum remarked on the photographer’s “robust, resilient gaze and above all, his boundless commitment to human beings.”5Hamaya Hiroshi: Shashin Taiken 60-nen(Hiratsuka: Hiratsuka City Art Museum, [1991]), n.p.

Why then was Hamaya compelled to photograph a vehicle on a bleak, muddy street in late 1953? To unravel the enigma, we need to trace both Hamaya’s life as a photographer and Japan’s postwar relations with the US.

Hamaya began taking pictures as a teenager in 1930, and he became a freelance photographer in 1937 after the Mainichi, a leading Japanese daily, published his work. By 1941, he was enmeshed in Japan’s war machine, recruited by the Eastern Way Company to produce heroic images of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy for Front, an avant-garde, multilingual propagandist periodical. Unhappy with Front’s manipulation of his photos, Hamaya resigned a year later. In 1944, as the US intensified its firebombing of Japan’s cities, Hamaya moved from Tokyo to Niigata, a port city on the Sea of Japan, whose punishing winters inspired Snow Land. Although drafted into the Imperial Japanese Navy later that year, he was discharged after a week for poor health. He marked Japan’s defeat on August 15, 1945, with a nebulous image of the sun in the sky above Niigata.

During the ensuing Occupation, the US established a massive bulwark of 250 military bases across Japan. When the Korean War started in 1950, the US armed forces used those bases to launch bombing raids and to attend to its wounded and dead soldiers. Although the Occupation formally ended in April 1952, the US kept its military bases, stipulating its terms in the US–Japan Security Treaty, which it imposed on Japan as the price for restoring Japanese sovereignty.

The security treaty, and the US military bases it authorized, generated tremendous public resentment in Japan throughout the 1950s, coalescing into massive demonstrations against the treaty’s impending renewal in June 1960. As daily protests engulfed Tokyo, Hamaya, seemingly everywhere at once, captured the defiant, hopeful faces of millions of demonstrators—from students and taxi drivers to shopkeepers, salarymen, and housewives, all terrified that the presence of the US bases would drag their country back into war. After the treaty’s renewal was rammed through the Japanese parliament, Hamaya’s camera witnessed the marchers’ optimism curdle into bitter rage at the hollow promise of democracy.

Magnum Photos had presciently contracted Hamaya to become its first Asian photographer in January 1960, and his arresting images of the uprising appeared in Paris Match and other European and Japanese magazines—but not in American publications, as Hamaya adamantly refused to allow them to be published there. In his afterword to Days of Rage and Grief, a photo book of protest images, Hamaya, never an ideologue, wrote, “War is the greatest violence of all.”6Hamaya Hiroshi, Days of Rage and Grief (Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1960), n.p.

Hamaya photographed the jeep in December 1953, after the US had signed the Korean armistice agreement and its bases were less active. Nevertheless, although the vehicle lacks the telltale white star of a US military transport, it is most likely an American military jeep since Otaru Bay was the chosen landing port of the US when it first occupied Hokkaido after Japan’s surrender. There is no question that the lopsided security treaty, evidence of which was strewn across Japan in the form of entitled GI’s and their menacing hardware, must have rankled Hamaya. His chronology states that he photographed Tokyo from the air in Japan’s first civil helicopter in 1953. Whether or not that helicopter flew him all the way to Otaru, he had found himself in a position to capture a bird’s-eye view of the jeep when he snapped the shutter, perhaps to belittle the symbol of occupation that still intimidated so many Japanese people.

Hamaya titled the image Composition, which suggests an alternative trajectory of his photography: Although he was largely self-taught, his images from the early 1930s are obviously influenced by Surrealism. Even Hamaya’s on-the-fly photos of the 1960 demonstrations betray an inherent formalism; in fact, he seems incapable of badly composing an image. When the J. Paul Getty Museum hosted the photographer’s retrospective in 2013, it paired him with his contemporary Yamamoto Kansuke, crediting Yamamoto with pioneering “a signature style that merged European-inspired Surrealist iconography with Japanese motifs and concerns.”7“Kansuke Yamamoto,” in “Japan’s Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto, March 26–August 25, 2013,” J. Paul Getty Museum website.

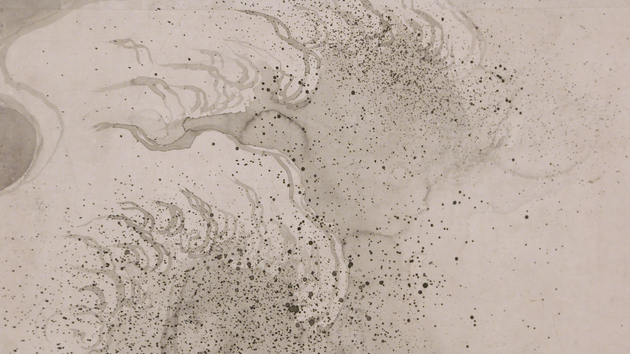

Although Hamaya and Yamamoto’s styles diverged, their black-and-white images on photographic paper are manifestly steeped in the aesthetics of sumi-e (charcoal ink painting), honed over centuries of practice by monks and painters for whom distinctions between figuration and abstraction were irrelevant. In Composition, perhaps Hamaya’s eye bypassed the trampled snow, perceiving instead the myriad shades between bright light and darkest shadow that his forebears had harnessed for the alchemy of charcoal ink, water, and brush on handcrafted paper.

Heartsick from the failed protests, Hamaya stopped photographing human beings after 1960, instead turning his lens to nature. In 1987, he became the first Japanese photographer to win the Hasselblad Award.

- 1“Remarks” from typewritten photograph record for Composition. 199.59, described as “Impression of a truck in the snow,” taken by Hiroshi Hamaya on December 1953, City of Otaru, Hokkaido, Japan. Department of Photography, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- 2Hamaya Hiroshi, Snow Land (Yukiguni; Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha, 1956).

- 3Hamaya Hiroshi, Japan’s Back Coast (Ura Nihon; Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1957).

- 4Shibusawa Keizo, preface to Snow Land, by Hiroshi, n.p.

- 5Hamaya Hiroshi: Shashin Taiken 60-nen(Hiratsuka: Hiratsuka City Art Museum, [1991]), n.p.

- 6Hamaya Hiroshi, Days of Rage and Grief (Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1960), n.p.

- 7“Kansuke Yamamoto,” in “Japan’s Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto, March 26–August 25, 2013,” J. Paul Getty Museum website.